CHAPTER 2

August 23, 2013

Madison woke up early. She sat up in bed, beneath the sloped white ceiling of her childhood room, within its painted red walls. She looked around. Leaning against the wall was the corkboard she would take with her to college, the bib from her national championship race pinned to the top left corner. Across the room was an old white desk on which Maddy had once dangled all the medals she won.

She had been waiting all summer for this day: the day she left for college. Three weeks prior, she had posted a picture on Instagram of one of the most beautiful buildings on Penn’s campus, writing, “T–3 weeks left.”

Leaving for college was all she and her high school friends talked about. Everything that summer pointed toward the next step. That’s how they talked about it, as if that summer was the equivalent of waiting in the boarding area for flights to exotic cities, anticipation clinging to everything. When they were sophomores and juniors at Northern Highlands, a few of their older friends would leave for school, then come home to visit and talk about how they wanted to transfer or take a semester off. Madison and her friends were baffled. They would say, “What? This is so confusing—how can you not like college?”

Madison’s sister Ashley was one of these older kids. She would come home every weekend from Penn State and talk about how miserable she was. Madison would press her, confused about what her sister was feeling.

No one among them, parents included, cautioned that the transition to college might be unexpectedly difficult. Part of why no parent did so must have been because they simply could not imagine it would be. College had been different for their generation. For one thing, they grew up without the Internet, without video games, without social media. Madison and her friends were the first generation of “digital natives”—kids who’d never known anything but connectivity. That connection, at its most basic level, meant that instead of calling your parents once a week from the dorm hallway, you could call and text them all day long, even seeking their approval for your most mundane choices, like what to eat at the dining hall. Constant communication may seem reassuring, the closing of physical distance, but it quickly becomes inhibiting. Digital life, and social media at its most complex, is an interweaving of public and private personas, a blending and splintering of identities unlike anything other generations have experienced. Jim and Stacy, Susie and Kobus, and millions of other parents hadn’t yet considered how the Internet might be affecting their kids, how it was fostering an increased dependence on outside validation, and consequently a decreased ability to soothe themselves. In 2013, these were just beginning to register as increasing concerns.

When Jim was growing up, good colleges were challenging to get into, but it wasn’t like it is today, when being a solid, diligent student is no longer enough. Students today must display excellence—not just competence—in numerous areas. The pressure to be great, not just good, is unrelenting. Believing that this pressure will simply disappear once kids arrive on campus seems like wishful thinking.

In Allendale, college is the ultimate destination, the goal toward which almost every student works. If coming of age used to mean summers and weekends working at 7-Eleven cleaning the Slurpee machine to make a few extra bucks to buy your favorite record, now it’s about checking boxes on a college application: becoming fluent in a second language, volunteering at a shelter, taking weekly SAT prep courses.

As move-in day approached, Maddy became anxious about the unknown. But she didn’t feel like talking about these feelings. She didn’t want to be the one to say, “Hey, you guys, is anyone else maybe a little scared about this?” What if they weren’t scared? What if, instead, her friends looked at her, heads tilted, like something was wrong with her?

And anyway, she was mostly excited. She wanted to focus on that.

She got out of bed that morning and waded through her messy bedroom, which looked as if her closet had exploded. Her room was always a disaster, clothes strewn across every available surface—hats and bags layered on hooks, the carpeted floor covered in worn clothes, the dresser with bottles of lotions and perfumes, the yellow chair stacked high with books and notebooks. The space was at complete odds with the rest of her life, which was meticulously presented, nothing out of place.

Maddy had already packed everything that mattered, preselecting an outfit for the day: light-blue high-waisted shorts, a pink bralette with a lace shirt, and tan gladiator sandals. And, of course, she wore a running watch on her right wrist so she could time her runs or anything else that needed measuring, such as her walk to class or her studying sessions.

Her roommate, Emily Quinn, was also on the Penn track team. The two had met earlier that summer during a team bonding weekend in the Poconos. Maddy wanted to arrive first at the dorm room, mostly because she liked to be first in everything, so she and Stacy left Allendale early.

When mother and daughter walked into the room, Stacy pulled out her iPhone and snapped a candid picture of her daughter. The room is bare, a twin bed on each side, a sallow light glowing from above—it is every dorm room everywhere. In the middle of the room, arms raised in a V, stands Madison, palms upward, eyes closed, mouth open in a smile. She’s holding a half-eaten red apple in her right hand, and she looks as if she has just stuck the landing on a dismount.

The picture is blurry, but the energy radiating from the image is unmistakable: freedom, euphoria.

Later that afternoon, after all the obligatory errands—to Target, to Office Max, to the Penn student center—Madison was settled in her new space. The bed was made: pink comforter, accent pillow with lowercase m. The desk area was tidy, efficient, colorful, with a pink iPhone dock and pink wastepaper basket, a small black fan on one level, a mug holding pens and pencils on the next. Beneath the desk was a purple plastic container filled with shampoo, body gel, and conditioner. And on the top corner of the tiered desk, angled to lean against the wall, was a piece of art, the background green, with fragments of encouraging sayings. The words, in varying sizes, were stacked like Tetris pieces.

Dream Big

Laugh Out Loud

Be Happy

Just Breathe

Follow Your Heart

Be Grateful

Create Your Own Happiness

Be Silly

Keep Your Promises

Nothing Is Worth More Than This Day

When Stacy and Jim had driven Ashley to Penn State, they had stayed overnight in Happy Valley. Ashley had begged them to. She just didn’t feel comfortable. But that afternoon at Penn, Stacy left a few hours after she and Madison had finished unpacking. Maddy was walking to the dining hall for dinner, and Stacy hugged her hard, then got in the car and returned to Allendale. Stacy was not concerned. During high school, Maddy had easily pivoted from one endeavor to the next, smoothly adapting to new sports, to harder classes. Jim and Stacy had always felt that Maddy, self-sufficient and clever, was the child they’d never have to worry about. This next step, to Penn, was harder than anything her daughter had previously faced, but Stacy had only seen her succeed, and believed she would again.

Plus, Penn was only ninety minutes away, not a full day’s drive like Penn State, and Maddy seemed excited, ready for the start of this next adventure.

Allendale is a mostly white, upper-middle-class town about twenty miles from New York City. It is farther from New York City than some of New Jersey’s more affluent suburbs, such as Teaneck and Ridgewood and Montclair, which are filled with families whose parents commute daily into Manhattan. Jim travels to the city once or twice a month and spends the rest of his time working from the basement of his home. The Holleran family included five kids: four girls (Carli, Ashley, Madison, and Mackenzie) and one boy (Brendan) who is also the youngest.

The Hollerans live on a street less than a mile from the high school Maddy attended. The road is not a cul-de-sac; it simply stops, becomes woods. Beyond the back of their property, and the soccer goal on which Maddy spent hundreds of hours practicing, is an open field with horses, where kids can learn to ride and jump. The town’s personality is flexible, depending on what each inhabitant wants to make of it: some see it as a bedroom community just miles away from the world’s busiest city; most see it as self-sustaining, self-contained, thankfully out of earshot of New York’s noise and bustle—a quiet haven in which to raise kids.

Northern Highlands High has about 1,300 students. The school also draws kids from surrounding towns, including Ho-Ho-Kus and Saddle River. Even so, Highlands is far from being one of New Jersey’s largest high schools.

Allendale’s small downtown offers a Starbucks as well as a few local shops, plus a bar and grill where many patrons know one another and where community members often host celebratory dinners. The well-manicured main street is like a slice of Americana, with the Stars and Stripes flying during the height of summer. The town has money: enough that most want for little, but not so much that its residents appear wasteful or excessive, as in some of New York’s other suburbs. Like hundreds of other boroughs across the country, Allendale has its distinguishing backstory and quirks: the town was named after William Allen, a surveyor for the Erie Railroad; it is home to the Celery Farm, a nature preserve through which Madison often liked to run; and scenes from the movie Presumed Innocent, with Harrison Ford, were filmed there.

Jim and Stacy moved to Allendale when the company for which Jim worked, Dow Chemical, asked him to relocate to the tristate area from Michigan. The move was a welcome one for the couple, as both had grown up on Long Island. The East Coast was more their style, and living there would bring them closer to both their families. Jim and Stacy had actually been high school sweethearts, but their story had a lengthy intermission. The two had known each other since they were little, played tennis together growing up, and dated in high school. But they broke up while in college: Jim at High Point, in North Carolina, and Stacy at Southern Illinois. Each married someone else. Stacy had a daughter, Carli, with her first husband, with whom she lived in Georgia, until the couple divorced. Around the same time Jim, too, divorced. He and his ex-wife did not have children.

Soon the two were back in touch. And not long after that, Stacy and Carli were moving to Michigan to be with Jim, to start a new family together. A few months before their move back east, Ashley was born. Madison was born two years later, on a beautiful, crisp fall day. In fact, the morning of her birth, Jim was at the soccer fields with Ashley, watching Carli play. He remembers the day clearly—how bright and blue the sky was, how he went to the hospital straight from the field, how later that day they added another child to their growing family. Over the next five years, Jim and Stacy would have two more children: Mackenzie, then their only son, Brendan.

Jim continued working for Dow Chemical as an account manager. He had majored in chemistry in college, but now worked in sales. Stacy, who had played tennis in college, began giving lessons, which she still does five days a week.

Jim and Stacy raised the kids as Catholics, but the most religious among them was Jim. As a family, they went to church just a few times a year, always on holidays, and all five kids were baptized and confirmed. Maddy took her confirmation seriously, choosing the confirmation name “Amelia” and later taking the first steps toward exploring her own, independent feelings about God and religion. Still, while in high school Maddy rarely attended church with Jim, who went faithfully, alone, every Sunday morning.

When Maddy was little, her hair was cut short and she loved to play outside. She called those years her “little boy days.” When she turned seven years old, she requested that her birthday party feature live animals—snakes and frogs—to be stocked in her family’s basement for herself and the neighborhood kids. Maddy loved the outdoors and all its creatures, and probably would have continued having animal parties and running around outdoors getting dirty if the world in which she and other girls live would have approved.

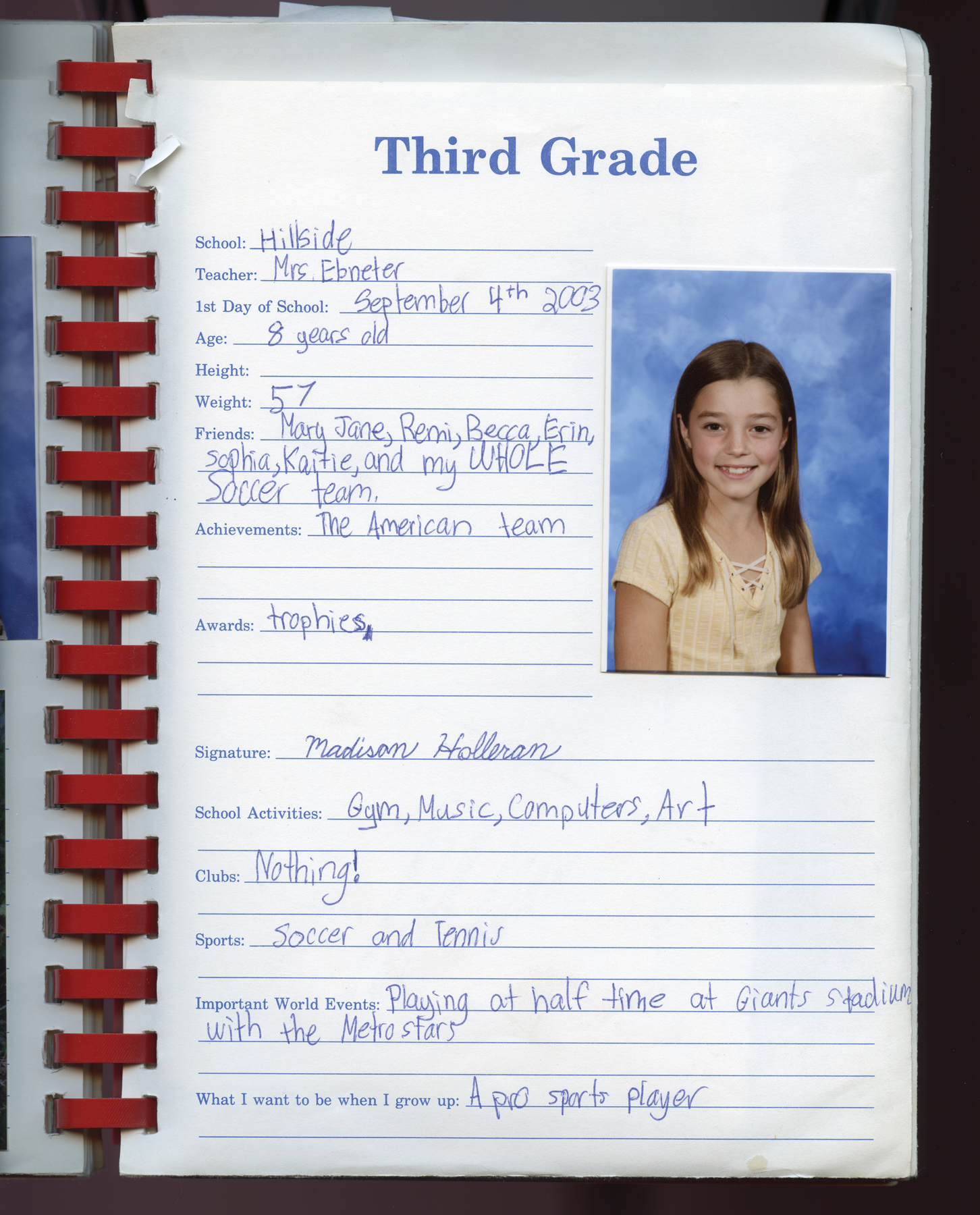

By the time Madison hit middle school, her “little boy days” were a distant memory. She had begun to grow out her hair a couple years before and started caring about how she looked, about the clothes she wore, about what other kids said about her. Still, much of who Maddy was as a little kid had stuck. As a second grader, she had fallen in love with art and soccer. Both helped her make sense of the world. In fact, during her first semester at Penn, Madison took an English class in which she had to give a speech. She started it with an anecdote about soccer: “When you were younger, what did you aspire to be? At some point in our lives, especially as children, we all question what we want to be in the future. In our naïve and hopeful minds, we set big dreams for ourselves. As a third grader I remember setting my goals towards becoming a professional soccer player. During recess I would hop into any pickup soccer games I could; regardless of whether boys were playing or girls. Some of my teammates and I were even invited to play as guests on the boys travel team, and even though they intimidated us a little, we were able to hang in there with them…”

(Holleran family)

Madison’s best friend growing up was MJ White, a friendship forged by the single-mindedness they shared. By second grade, they were playing together on the local club soccer team, forming friendships that would last through high school. And at school, MJ and Madison would spend their free time drawing. One year, they started drawing dogs—different breeds, different names for each. The paper dogs were like pets, but without the hassle and long-term commitment. When they first started, they would look at each other and say, “We have to make them perfect, okay?” And both would nod. Soon after, they were drawing dogs every free moment. Once they built up a collection of a decent size, they decided to sell their paper pets to family and friends. The two friends donated the proceeds to buy hats and gloves for the homeless.

Art became a release for Maddy. During middle school, she would spend her free time sketching. One teacher allowed students to paint different parts of the hallway—creative café, the teacher called it—and Madison would take part every day. Even as she got older and other pursuits became cooler, Maddy continued drawing. She liked that she could control the space. The whiteness of the paper could become anything she wanted—and also only what she wanted. If Madison focused intensely enough, if she was willing to block out distractions, she could produce something flawless.

Soccer wasn’t like that. Everything happened in rapid succession, one decision forcing the next. But on the field, a different kind of perfection could be attained. Occasionally a play would unfold with such unexpected rhythm as to feel choreographed, and a kind of beauty existed in that chaos.

For years, Maddy had also played tennis, the family sport. She was good at tennis—really good. So good, in fact, that when she and Jim would attend the U.S. Open, as they did every year, she would watch and wonder if she could someday play at the highest level. Jim believed she could, of course. He believed she could do anything.

But eventually, around the start of high school, Madison dropped competitive tennis in favor of soccer. When asked why, she said she didn’t want to play an individual sport. She spent enough time inside her own head—thoughts bouncing around, sharpening inside her mind—that playing tennis felt too isolating. The sport was as much mental as physical: walking along the baseline after each point, trying to rally if things weren’t going well, or to stay grounded if they were. The roller coaster of emotions that was tennis was more than Maddy wanted to handle. Where tennis could trap you inside your own mind, soccer was open, even freeing. And Maddy was also really good at it.

Emma Sullivan and Jackie Reyneke started playing for the local soccer club in kindergarten. Jackie’s dad, Kobus, coached the team, called the Americans. When Madison and MJ joined, followed by Brooke Holle, another talented kid from Upper Saddle River, the Americans became a juggernaut. Their reputation grew as one of the most elite local teams in the state. Although most of them could have upgraded to a more prestigious team, the girls continued playing together through eighth grade. They didn’t want their time together to end, but they knew that by the time they reached high school they needed to switch teams. They needed bigger tournaments—the kind college recruiters attended—and better competition.

For the girls, leaving the Americans was the end of an era. Madison, Erin, Jackie, Emma, and Brooke were going to high school at Northern Highlands, a public school, while MJ would move to a local private school. They would all stay friends, of course, but Maddy became closer to Emma, Jackie, and Brooke, because they saw one another every day.

The Northern Highlands coaches, teachers, and students all knew of Madison before she started high school. That was partly because of Ashley, who was beginning her junior year, but mostly it was because of how Maddy had distinguished herself athletically, academically, and socially. People saw her as someone with endless promise. She was supposed to make varsity as a freshman, get straight As, and generally rule the school.

The summer before starting high school, Maddy became anxious. One night, a couple weeks before the first day of freshman year, she and her friend Trisha went over to MJ’s house and hung out in the backyard eating ice cream and talking. This was the first time any of Maddy’s friends had seen her unsteady, doubting. The transition to high school was the first major challenge for all of them—the first life change they faced with concerns beyond who they might sit next to on the bus. That night at MJ’s, Madison had just gotten back from a sleepaway soccer camp at Rutgers, and the first day at Highlands was looming.

Growing up, Madison had spent hundreds of hours, and often well into the evening, kicking the ball into the netting of a floppy white goal that Jim had constructed in their backyard. She studied for tests until she knew every answer. She was doing everything she could, and yet so much still seemed uncontrollable.

“I’m just nervous,” Maddy said that night at MJ’s.

“About what?”

“What if the older girls don’t like me? What if I don’t make varsity?” She began crying. MJ and Trisha said all the right things: that she would be great, that everyone would love her, that everything would work out. But their words couldn’t make it better. Words meant little. Only excellence helped chip away at self-doubt. And so she excelled.

She didn’t make varsity as a freshman, but she was called up repeatedly and earned important minutes during the playoffs. And by junior year, Madison had become exactly the person everyone anticipated she might. She was a starter on the varsity girls’ soccer team, scoring thirty goals that season as Northern Highlands won the state championship. At one point during the title game Maddy had to leave the field with an injury, and everyone held their breath, worried she had blown out her knee. But it was only a tweak and she soon returned to the game, and Highlands won on Maddy’s sixteenth birthday.

She started running track during sophomore year, mostly to keep in shape for soccer, but each time she raced, she seemed to get faster. This surprised no one. She was a natural athlete with a beautiful stride, the mechanics already in place—a finely tuned race car that had finally found the track.

In school, she was one of the best students in her class, always sitting in the front row with her notebook open. Her reputation: diligent. While some kids skipped assignments and asked to borrow answers from friends, Maddy did all her own work, always. And when she would walk the halls, the younger girls craved her attention, commenting on her outfit or offering congratulations about the latest game or race, anything to stay in her presence just an extra beat, to absorb whatever flicker of attention she might offer. She would mostly smile and laugh. People liked to be around her because she always seemed to be laughing. And when she wasn’t, she made sure she was around friends who could empathize, who understood the anxiety that accompanied ambition.

Maddy was very popular—among both girls and boys. The boys loved the way she looked, but there was also something alluring about the unattainable aura she projected; dating and boys—usually the centerpiece of someone’s high school experience—were low on her list. “She had so many other things going on,” Emma said. “It wasn’t her main focus. Yeah, it was there. She could have pursued a lot of that. But she was so focused on doing well in sports and school. Dating just wasn’t her main goal.” Throughout high school Maddy casually dated and flirted at parties, but nothing became too serious.

Her commitment to sports eventually paid off. By sophomore year, her first full season on varsity, numerous college soccer coaches had written Maddy expressing interest. And by junior year, dozens of additional programs had her on their radar. She was one of the best players in the state, and had strong academics—a perfect candidate for the Ivy League. Harvard was a possibility. So was Penn. Maddy had been charmed when she and Emma took a visit to Philly during their junior year. She’d fallen in love with the school’s proximity to a major city, its beautiful architecture and cachet; but the Penn soccer coach stopped recruiting her after watching a game in which she played poorly.

A wave of disappointment washed over Maddy, but in its wake came an official scholarship offer from Lehigh. The head coach there, Eric Lambinus, was high on her, believed she could be a great college player. When Lambinus watched Maddy, he saw skill and potential, fueled by her passion for the game. Lehigh had been recruiting Maddy for more than a year and had developed a close connection with her. It was a Division I program and a great liberal arts school. Of course, no college could match the allure and name recognition of the Ivy League. But most of Maddy’s friends and family thought Lehigh was the perfect fit for her: she could contribute right away on the field, and the academics would be challenging but not all-consuming.

The Lehigh coaches devoted hundreds of hours to recruiting her. They talked with her on the phone regularly, traveled to watch her games, and hosted her on campus three times. They came to know her as well as any kid they had recruited. And in April of her junior year, Maddy gave Lehigh a verbal commitment, which was essentially a promise that, in November of her senior year, she would sign a national letter of intent to play soccer for them. The “verbal” was not legally binding, but most other coaches stop recruiting a player who has given this commitment. And most coaches did stop recruiting her—at least in the soccer world. The Lehigh coaches were thrilled.