1

Peter: Bishop of Rome?

About a mile outside the ancient walls of the city of Rome is a small chapel on the Via Appia, the old Roman road. The name of the chapel is Quo Vadis, a Latin expression meaning Where are you going? The legend attached to the chapel was first recorded in the apocryphal Acts of Peter in the late second century. According to the legend Peter, fearing for his life in the year 64 during the persecution of Nero, fled Rome. As he raced down the Via Appia he met a man walking toward the city whom he recognized as the Lord. “Where are you going,” Peter asked him. “To Rome, to be crucified again.” With that Peter realized that his duty was to return to Rome and stay with his flock during this difficult time, which probably meant dying as a consequence. The legend has no foundation in fact, but it raises the crucial question: did Peter really come to Rome and suffer martyrdom there? I repeat: the whole subsequent history of the papacy depends on an affirmative answer to the question (see fig. 1.1).

The story of Peter and the papacy begins, however, not with Rome but with the New Testament. For Christians the New Testament is an inspired book, written under the guidance of the Holy Spirit as the fundamental and authentic testimony about the life and message of Jesus. It is the touchstone of faith for the Christian church, to which the church must always have recourse and from which it can never deviate in its basic beliefs. For historians and biblical scholars, in contrast, the New Testament is a collection of documents written within a century of Jesus’s death by different authors with different concerns and viewpoints. It consists of four historical narratives (the gospels), a narrative of the spread of Christian teaching in the first generation (the Acts of the Apostles), and a number of epistles, especially those by Paul, and an apocalyptic vision (the book of Revelation).

For our purposes two things are remarkable about that collection, even aside from its purportedly inspired character. The first is the sheer quantity of information those documents provide about Peter.

He is, next to Jesus himself and possibly Paul, the most fully documented of any New Testament character. Second, the sources are consistent in the picture they paint of him. What do we know? Named Simon Bar Jona, he was a fisherman like his brother Andrew. He had earlier been a disciple of John the Baptist. He lived in Capernaum on the shores of the Lake of Galilee with his wife and his mother-in-law. He was warm, loyal, impetuous, and a wonderful friend. At the Garden of Gethsemane he drew his sword in defense of Jesus and cut off the ear of a servant of the high priest.

He had a dark side. He was not as steadfast and brave as he imagined himself to be. At the Last Supper (Luke 22), Jesus said to him, “Simon, Simon, behold Satan demanded to have you, that he might sift you like wheat. But I have prayed for you that your faith may not fail, and when you have turned again, strengthen your brethren.” To which Peter said, “Lord, I am ready to go with you to prison and to death.” Then Jesus, “I tell you Peter, rock, the cock will not crow this day until you three times deny you know me.” It turned out, as we well know, just as Jesus predicted. But we also know from the early chapters of the Acts of the Apostles that after Jesus’s resurrection Peter became a fearless and steadfast preacher of the Good News.

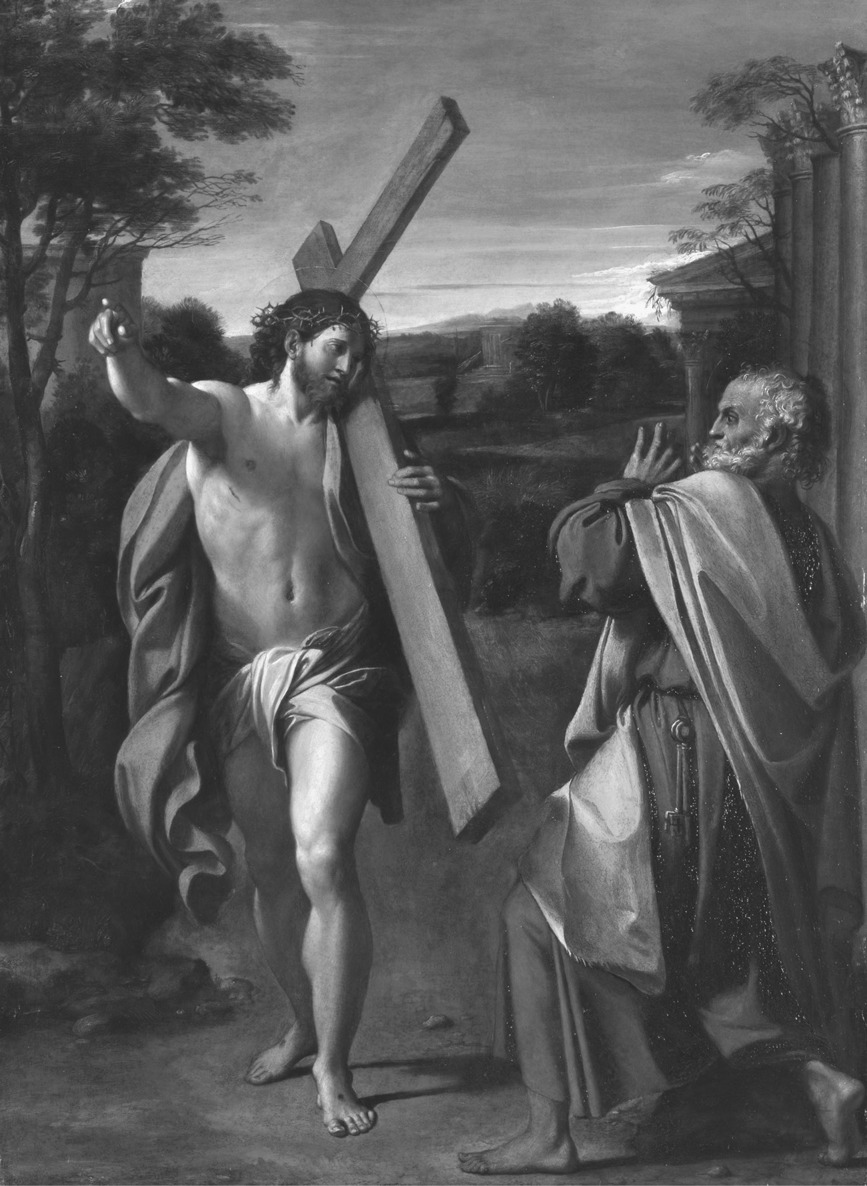

1.1: Saint Peter, “Quo vadis, Domine?”

Carracci, Annibale (1560–1609). Christ appearing to Saint Peter on the Appian Way (Domine, Quo Vadis?), 1601–1602. Oil on wood, 77.4 x 56.3 cm. Bought, 1826 (NG9).National Gallery, London, Great Britain.

© National Gallery, London / Art Resource, NY

Just as clear in the New Testament as his character is the preeminence Peter enjoyed among Jesus’s inner circle, “the Twelve,” and then later in the early church. According to Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians, which is the earliest document in the New Testament to mention Peter, Paul went to him after his conversion on the road to Damascus to learn about the faith. Peter gave Paul a crash course in fifteen days. In chapter 2, however, Paul confronts and rebukes Peter when Peter tries to back down from his previous table fellowship with Gentiles. What is important here, however, is not that Paul withstood Peter to his face, but that Paul could vindicate his own authority by a backhanded recognition of Peter’s—that even Peter backed down.

In the first twelve chapters of the Acts of the Apostles, Peter is the dominant figure. Leader of the church in Jerusalem, he presided at the election of the successor to Judas the traitor. He spoke for the church on Pentecost and worked miracles in Jesus’s name. He was an apostle to the Jews but also to the Gentiles, as is clear from the story of his conversion of the Roman centurion Cornelius. Rescued from prison by an angel, he was without question the center and focus of the narrative of these chapters.

In three of the gospels Peter is the first of the Twelve to be called by Jesus. In the synoptic gospels—Matthew, Mark, and Luke—he is the first mentioned in every list of the Twelve, and he acted as their leader and spokesperson. Jesus chose him, along with Andrew and John, to witness his Transfiguration on Mount Tabor, and he took the same three to watch with him in the Garden of Gethsemane. In Mark’s gospel after the resurrection the angels told the women to go tell “the disciples and Peter” about what they have seen. In John’s gospel Peter is the first to enter the tomb.

Two passages, however, are particularly crucial. The first is from Matthew, chapter 16:

He said to them, “But who do you say that I am?” Simon Peter replied, “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God.” And Jesus answered, “Blessed are you Simon, Bar-Jona! For flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my father in heaven. And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the powers of death shall not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven.

The meaning of the passage has been much disputed, especially since the Reformation. Some biblical experts argue, for instance, that the church is built not on Peter but on the confession of faith that Peter made, or even on Peter’s faith itself. In other words, built on the belief in Jesus’s special person and mission, which Peter happened to articulate. The consistent papal interpretation is that the church is built on Peter himself—and then on his successors through the ages. The passage is, in any case, extraordinary—no other disciple is singled out from the others in such a striking way in any of the four gospels.

The second passage is from the last chapter of John’s gospel and is set on the shore of the Lake of Galilee after Jesus’s resurrection:

When they had finished breakfast, Jesus said to Simon Peter, “Simon, son of John, do you love me more than these?” He said to him, “Yes, Lord: you know that I love you.” He said to him, “Feed my lambs.” A second time he said to him, “Simon, son of John, do you love me?” He said to him, “Yes, Lord; you know that I love you.” He said to him, “Feed my sheep.” He said to him the third time, “Simon, son of John, do you love me?” Peter was grieved because he said to him a third time, “Do you love me?” And he said to him, “Lord, you know everything; you know that I love you.” Jesus said to him, “Feed my sheep.”

These two passages dramatize what all the other passages in the New Testament about Peter point to: his leadership role and his special relationship with Jesus. That much is clear. Two sets of questions crucial to the papacy, however, remain to be answered. First, was the leadership Peter exercised unique to him, so that it was not to be passed on to others in the church? Was it so identical with the person of Peter and with the situation of the first generation that it ended with him? Or, did Peter signify a pattern that was to persist after his death? Did Peter launch a trajectory that was to continue in the church until the end of time? The simple answer is that it is difficult to understand why the authors of the New Testament would have paid so much attention to Peter if his role in the church had no significance beyond his lifetime.

The second question: what happened to Peter? Despite his prominent role in the Acts of the Apostles up to chapter 12, he disappears from the narrative after that, and Paul takes over. How did Peter end his days? More specifically: did he go to Rome, assume a leadership role in the Christian community there, and die a martyr’s death under the Emperor Nero?

To answer that question we need to look at a range of evidence, because no one piece of it states in straightforward and unambiguous language either that Peter ever went to Rome or that he died there. Nonetheless, the evidence all points in that direction, and none contradicts it or points in another direction. The cumulative effect of this circumstantial evidence is persuasive. Moreover, even before we look at the evidence, we must remember that Rome was the communications center of the empire. Anybody with a message to spread would do well to go there, and Peter surely had a message to spread and a leadership role that required him to spread it. It seems almost inconceivable that for such a prominent figure in the New Testament the early community would have so soon after the event mistakenly remembered him. The consensus today among scholars from every religious tradition (and from no religious tradition) is that, from a strictly historical viewpoint, Peter almost certainly lived his last days in Rome and was martyred and buried there.

The evidence is textual and archeological. The New Testament provides a few clues. In the passage from the last chapter of John quoted above, Jesus predicts a martyr’s death for Peter. More important is the ending of the First Epistle of Peter which, even if it was not written by Peter himself, was written under his inspiration. “By Silvanus, a faithful brother as I regard him, I have written briefly to you, exhorting and declaring that this is the true grace of God: stand fast in it. She [your sister church] who is in Babylon, who is likewise chosen, sends you greetings, and so does my son Mark.” Babylon was a common designation for Rome among Christians, a cryptic name necessary in time of persecution for a world power hostile to the Gospel. The passage suggests, or even indicates, that Peter is in Rome at the time the letter was written, which was probably about the year 63.

Sometime around the year 96 a letter, unsigned but written by a presbyter in Rome named Clement, was sent in the name of the Christian community in Rome to the community in Corinth. In one passage the author brings up Peter in a way that suggests both a special Roman relationship to him and direct information about what he suffered. “Let us set before our eyes the noble Apostle Peter, who by reason of wicked jealousy, not only once or twice but frequently endured suffering, and thus bearing his witness went to the glorious place that he narrated. By reason of rivalry and contention Paul showed how to win the prize for patient endurance.”

The passage does not give us a two-plus-two-equals-four indication that Peter and Paul went to their deaths in Rome, but that is a reasonable inference from a document written just a generation after the events would have happened. About fifteen years after that, another leading figure in the early church, Ignatius, bishop of Antioch in present-day Syria, wrote a series of letters to different churches when he was on his way to Rome, where he was going to be put to death for his Christian faith. In his letter to the church in Rome, he said in one passage, “I do not command you as Peter and Paul did. They were apostles. I am a convict. They were at liberty. I am in chains.” The passage might mean that Ignatius could not command the Romans as if he had the authority of Peter and Paul, but that interpretation seems less likely than that Peter and Paul in some way commanded or headed the Church of Rome.

Much further along in the second century Saint Irenaeus, bishop of Lyons, wrote that the church had been “founded and organized at Rome by the two glorious apostles, Peter and Paul.” Irenaeus’s writings were well known in his day, and no one, in the Mediterranean communities, which were jealous of any connection they might have had with the apostles, contested his assertion about the Roman church.

From the textual evidence, then, it is clear that by the end of the second century, at the latest, well informed Christians were convinced that Peter and Paul lived and died in Rome. Archeological evidence supports the textual. The most impressive instance of it comes from excavations under Saint Peter’s basilica conducted in the middle of the twentieth century. As mentioned, Constantine built the original church, which was substantially finished by the year 330. He built it where he did because by that time it was taken for certain that that was where Peter either died or was buried or both. That church was torn down in the sixteenth century to make way for the church we know today. But the new church was built on exactly the same spot, and the new altar located precisely where the original altar had been. In the early sixteenth century, when work on the new church was just beginning, the architect Bramante wanted to change the orientation of the church and move the altar, but Pope Julius II would not hear of it because he was not going to touch the tomb. And by tomb he meant Peter’s.

That was the sixteenth century. We need to fast-forward to 1939. Monsignor Ludwig Kaas, then the administrator of the basilica, asked Pope Pius XI’s permission to clean up the area under the church called the Sacred Grottoes, which is where many of the papal tombs were located. The area was in disarray. For reasons still not clear, the pope denied permission but, curiously enough, that is precisely where he wanted to be buried.

When Pius died on February 10, 1939, Kaas went down into the Grotto area looking for a place to install the pope’s tomb. In the process he ordered a marble plaque to be removed from the wall and, as it was being done, the wall behind it collapsed and exposed an ancient vault. What else was there, in this now exposed area? When the new pope, Pius XII, heard of what happened, he ordered a full-scale investigation of the area, which was carried out over a ten-year period, followed by further excavations begun in 1952. The excavations uncovered a number of ancient tombs and a cemetery dating no later than the second century. They also uncovered a red-wall complex into which was built a small edifice, called a Tropaion (tomb or cenotaph), and alongside the edifice the wall containing devotional inscriptions referring to Peter.

The results of the excavations were published. Controversy ensued about the way the excavations were conducted and about conclusions drawn from them. Nonetheless, two facts are certain and uncontested. First, in the area of the excavations right under the main altar there was a shrine dedicated to Peter, seemingly a burial place, and dating from about 150. At the time the shrine was built, Christians surely venerated the spot as sacred to Peter. Second, a century and a half later Constantine expended tremendous effort to build the church where he did. He had to desecrate a Roman cemetery and then move tons of dirt to level the area. Then he saw to it that the altar be located precisely over the spot where the little shrine was found.

Since all the evidence available, both textual and archeological, confirms the traditional belief about Peter and Paul in Rome and none contradicts it, the tradition can be accepted as true beyond reasonable doubt. Three questions, however, remain. First, did Peter and/or Paul found the Christian community in Rome? To that question the answer, despite what Irenaeus said, is a clear negative. The community was already in existence. Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, surely written before he went there, is proof positive of the fact.

The next question: was Peter the first pope? The answer depends on the answer to the third question: was Peter the first bishop of Rome? And that answer is both yes and no. The earliest lists of popes begin not with Peter but with a man named Linus. The reason Peter’s name does not appear is because he was an apostle, which was a super-category, much superior to pope or bishop.

But did he, apostle though he was, actually function as bishop, as the leader and supervisor of the church in Rome? The Christian community at Rome well into the second century operated as a collection of separate communities without any central structure. In that regard it was different from other cities at the time where, as in Antioch, Christians thought of themselves and acted as a single community over which a bishop presided. Rome was a constellation of house churches, independent of one another, each of which was loosely governed by an elder. The communities thus basically followed the pattern of the Jewish synagogues out of which they had developed. By the middle of the first century Rome had a large and prosperous Jewish community, with maybe as many as fifty thousand members, who worshiped in over a dozen synagogues.

If a bishop is an overseer who leads all the Christian communities within a city, then it seems Peter was not the bishop of Rome. But that is a narrow and unimaginative approach. Peter being Peter, who had eaten and drunk with Jesus and was a witness to his resurrection, surely must have exercised a leadership role in Rome that was greater than that of any single elder/presbyter. It is inconceivable that Peter, an apostle, came to Rome, the capital of the empire, and did not have a determining role in that community whenever decisions were made. If that is true, then it follows that Peter can, with qualification but justly, be called the first bishop of Rome. And if he is the first bishop of Rome, then he is the first pope.