6

Greeks, Lombards, Franks

In your mind’s eye imagine three scenes. The first takes place in Rome about fifty years after Gregory’s death. Picture for yourself a pope, desperately ill. He is in the cathedral of Saint John Lateran, where he has taken refuge as a place of sanctuary for protection against the agents of the emperor. The agents violate the sanctuary, seize the pope, strip him of his pontifical robes, and smuggle him onto a ship heading for Constantinople. Once in Constantinople, the pope, Martin I, is put on trial on trumped-up charges of treason. He is found guilty, dragged in chains through the streets, publicly flogged, and sentenced to death, which is commuted to life-imprisonment. The pope dies six months later from cold, starvation, and harsh treatment.

Fast-forward a hundred years. The second scene takes place in what was once Gaul, now the kingdom of the Franks. Picture for yourself a pope and his entourage in penitential garb in the presence of the king of the Franks. They fling themselves on the ground before the king, beseeching him, for the sake of Saint Peter, to deliver them and the people of Rome from the Lombard threat. The situation, they insist, is desperate.

The third scene. In the same location picture the same king. Picture the same pope, not in penitential garb but seated on a horse with Pepin, king of the Franks, on foot holding the horse’s bridle as if he were a mere groom, servant of the pope. The pope is Stephen II, the first pope in history to cross the Alps into northern Europe. He has sought protection by turning his efforts not to Constantinople in the East but to the kingdom of the Franks to the north and west. His plea, unlike so many identical pleas to the court of Constantinople, has been heard and will be acted upon.

These three scenes dramatically illustrate the revolution that took place in the century and a half after Gregory’s death. The revolution was slow, gradual, and painful, but by the middle of the eighth century it had been accomplished. The relationship between the pope and the emperor in Constantinople that had prevailed since Constantine’s day was transferred to another ruler in northern Europe. Pope Leo III will solemnize and ritually proclaim it a few decades later when in Saint Peter’s basilica on Christmas Day, 800, he crowns Pepin’s son Charlemagne as emperor and then kneels in homage before him.

The two centuries leading up to that momentous coronation were filled with conflict and confusion. During Gregory’s time and even during Martin I’s, the traditional center of authority continued to be Constantinople, still the capital of the empire, still glorying in the prestige of Constantine, and still insisting on its traditional roles regarding the Western church. In actual fact, however, its effective political and military presence in the West had come close to disappearing. Moreover, by Martin’s pontificate in the middle of the seventh century, it had its hands full with war against the Persians, with Slavs raging against its authority in the Balkans, and with the new threat from Arab Muslim forces that would overrun the Middle East, North Africa, Spain, and even southern France.

Imperial impotence in providing the papacy and Rome with the protection they needed is the context that made the revolution almost inevitable. Fraying the relationship on another level were the claims by the patriarchate of Constantinople of equal, or almost equal, standing with the see of Rome, claims that the emperors implicitly or explicitly supported. The alienation between the Greek-speaking and the Latin-speaking churches that achieved its symbolic expression only in 1054 with the Great Eastern Schism had been in the making for centuries and was another factor in the alienation between the papacy and the emperors.

The doctrinal disputes that wracked the East in ways they did not wrack the West but that implicated the popes exacerbated the problem, as the case of Martin I makes clear. In the East the Monophysite heresy, which postulated Christ had only one nature, divine (just the opposite of Arianism), had for two centuries divided the church and endangered the empire, which needed to rally all parties to deal with the military threats to it. In an effort to conciliate the Monophysites while still affirming the orthodox view that Christ had both a human and a divine nature, a doctrine sprang up asserting that he had only a divine will, into which his human will was absorbed—Monothelitism. The compromise only worsened the situation, and finally in 648 Emperor Constans II forbade the use of formulas expressing either view.

In the early stages of the controversy, Pope Honorius (625–638) had embraced Monothylitism, but his successors, Pope John IV (640–642) and especially Pope Theodore I (642–649), emphatically repudiated it. Theodore, a Greek, born probably in Jerusalem, son of a bishop, had come to Rome most likely as a refugee from the Arab conquests. He excommunicated two patriarchs of Constantinople for their teaching on the subject, in retaliation for which imperial troops in Rome looted the papal treasury.

When Martin came to the throne in 649, he faced a tense situation. Born at Todi in Umbria, he had served Theodore as his apocrisiarius in Constantinople, where he became thoroughly familiar with the issues and with the personalities involved in the controversy. He showed his independence immediately upon being elected by going ahead with his installation without waiting for approval from Constans II.

He then organized a synod in Rome attended by over a hundred bishops as well as some Greek clerics exiled because of their stance on the doctrinal issue. The synod, one of the most theologically sophisticated to be held in the West, lasted a month. It repudiated not only Monothylitism but also Constans’s decree forbidding discussion of the matter. The emperor, infuriated at these challenges to his authority, ordered his exarch to arrest Martin, but the attempt failed because of Martin’s widespread support in Rome. Having learned his lesson, the emperor subsequently sent an armed force and achieved his goal, which led to Martin’s bitter death in exile. The church in Rome, although it remained utterly passive during Martin’s ordeal and made no effort to help him, soon afterward began to venerate him as a martyr.

The next two popes exhibited none of Martin’s courage in facing the emperor, and when Constans visited Rome for twelve days in 663 Pope Vitalian (657–672) showed him every honor and orchestrated a gift-bearing procession for him and his soldiers at the tomb of Saint Peter. During his visit Constans had the Pantheon and other public buildings stripped of their bronze tiles and adornments, which were melted down to be taken back to Constantinople. Few things he did made his memory more roundly hated in Rome. When five years later Constans was brutally murdered in his bath, the Romans shed no tears.

During the next fifty years relations between the two authorities seesawed back and forth between recriminations and reconciliations. Constans’s successor repudiated Monothelitism, and in 680–81 the Third Council of Constantinople affirmed the orthodox teaching. Nonetheless, in the West the conviction grew stronger and stronger that the emperors could not be trusted—they failed to honor their obligations to Rome, they espoused heresy, and they exacted heavy taxation from the West, in return for which they gave nothing. The popes, by contrast, expended tremendous care on the city, upheld orthodoxy, and bore the heaviest burden of imperial taxation.

Meanwhile an amazing thing had happened in Rome. Because of the many problems in the East—political, military, and doctrinal—more and more refugees from there flocked into the city. Pope Theodore was one of the first to come to public notice. Of the thirteen popes elected between 687 and 752 only two were Latin-speaking. These popes tended to be even more anti-imperial than their Italian counterparts, which led to further deterioration in the East-West relationship. They brought with them Greek icons and liturgical practices, which resulted in a new era of church building and decoration in Rome, some of it absolutely splendid and still visible today. Into the ceremonies, liturgical and other, of the papal court infiltrated more sumptuous and symbolically mystical elements that were reminiscent of court rituals in Constantinople and that suggested the sacredness of the person of the pope.

In 726 the emperor Leo III further damaged imperial prestige by embarking in his dominions on a campaign of icon-smashing that for a century was carried on with varying degrees of intensity by most of his successors. A complicated and bitter affair, the campaign was related to the declining fortunes of imperial prestige. The major protagonists for the iconoclasm were the emperors, beginning with Leo who, looking for a scapegoat for his troubles, found it in the sin of idolatry practiced by his people, that is, their veneration of icons.

Just how much actual image-smashing took place during the long Iconoclast period is not known, but occur it did, with the stripping of mosaics and frescoes from churches, the destruction or expropriation of altars and church furnishings, the burning of relics, and the destruction of icons outside church precincts. The phenomenon confirmed Western conviction that the emperors had once again become heresiarchs, a conviction strengthened by the laments of Greek refugees from iconoclast persecution streaming into Rome. Leo could not have done more to worsen the situation than when in 732 or 733 he, in dire financial straits, confiscated all the estates of the Patrimony of Saint Peter in Sicily and southern Italy, a major source of papal income.

The fact that the Lombards had become Catholic Christians did not quench their ambition to consolidate and expand their political domination of the northern half of the Italian peninsula and much of the southern half. By 751 they had captured Ravenna and thus put a definitive end to the exarchate, the emperor’s only post in the West. In less than a year the Lombard king Aistulf appeared at the gates of Rome and demanded an annual tribute. Pope Zachary, the last of the Greek popes and the last pope to feel any allegiance to the emperor, died at this crisis point. He was succeeded by Stephen II (752–757), a Roman from a wealthy and aristocratic family, the man who would effect the great turn from Constantinople to the kingdom of the Franks.

In that kingdom earlier in the century Charles Martel, officially Mayor of the Palace, had emerged as the unquestioned political leader. A brilliant general, he in a series of wars united the Franks in a way they had never been united before, and he cast into an obscure shadow the kings in whose name he served. The Arab Muslims had by the third decade of the century conquered all of Visigoth Iberia, crossed the Pyrenees, and were threatening Poitiers. In 732 Charles defeated them decisively in the famous battle of Tours, which marked the end of Muslim advance there. Here in Martel was a political and military leader, a Catholic Christian, who had the resources to aid the ever more desperate popes.

Pope Gregory III (731–741), a Syrian by birth and equally fluent in both Latin and Greek, had seen in Charles a potential champion, and in 739 and again in 740 he sent embassies to him with impressive gifts and the offer to confer upon him the title of consul and the rank of patrician if he would but come to the aid of the church. Charles received the envoys graciously but had no interest in going to war with the Lombards, erstwhile allies of his in his northern campaigns. Into the lap of the next pope, Zachary, fell, however, a golden opportunity. Charles and Pepin, his son and successor, though they ruled the kingdom, had no official title indicating the legitimacy of the authority they exercised de facto. In 750, after Charles’s death, Pepin sent a chaplain to Zachary to ask the loaded question of who deserved the title of king, to which Zachary replied that the royal title belonged to the person who performed the office. The next year Saint Boniface, the English missionary to Germany, crowned Pepin king of the Franks, and with that a new dynasty was born—with papal approval and blessing.

Zachary died the next year, but the stage had been set for Stephen’s fateful trip across the Alps in 754. Stephen was elected with the Lombards at the gates of Rome. Although Aistulf withdrew, Stephen realized that the city would never be safe until some way was found to contain the Lombards, and he fully realized that it was useless to implore help from Constantinople. He turned to Pepin and asked to visit him to discuss the situation. Pepin responded with unexpected alacrity and generosity, surely in gratitude for the great benefit that Zachary had conferred upon him. He sent Bishop Chrodegang of Metz and his own brother-in-law Autcar to lead the entourage that ensured the pope’s safety during the trip and accompanied him into his kingdom.

On January 6 Stephen and Pepin met at Ponthion, south of Châlons-en-Champagne in the northeast of present-day France, where Stephen got a warm reception. The next day, the penitential procession and prostration of the pope and his party took place. Stephen soon received a response from the king that surpassed his wildest expectations. The two men continued to meet for the next several months, which culminated at Easter with a meeting near Laon. Pepin promised to aid the pope and the people of Rome in their distress, a promise he was fully capable of keeping.

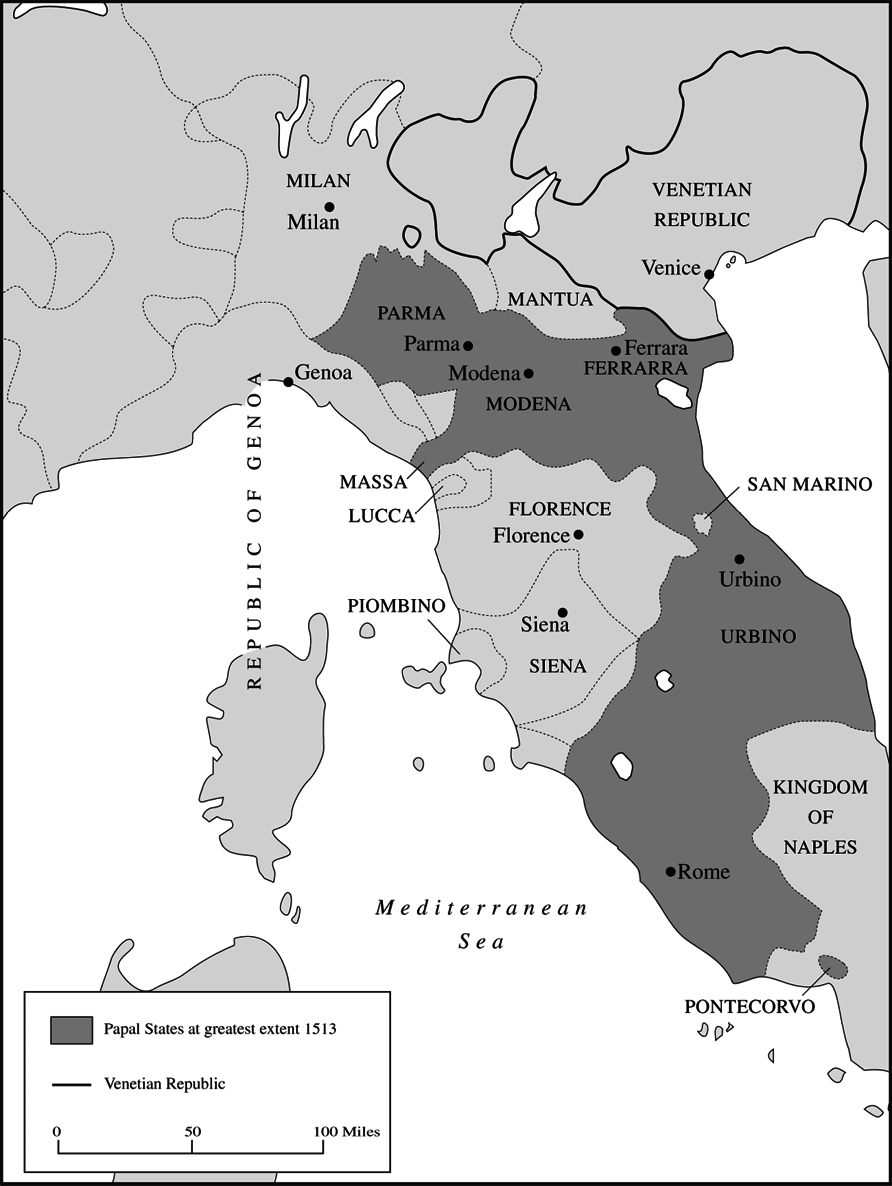

But he went far beyond that. In writing he guaranteed that Saint Peter had rightful possession of the Duchy of Rome (a large territory surrounding the city), which was astounding enough. He further guaranteed possession of Ravenna and the territory of the old exarchate, and seemingly other extensive territories north and east of the duchy held by the Lombards and reaching to the exarchate. This guarantee became known as the Donation of Pepin, the origin and foundation of the Papal States. The moment marked the beginning of an era of papal history that would continue for more than eleven centuries, during which the popes claimed they were rulers in their own right over an extensive territory. It was about this time or a little later that the “Donation of Constantine,” one of the most famous forgeries of all time, was composed and began to circulate. The document, mentioned earlier, was at least in part an attempt to give Pepin’s action a precedent in a supposedly similar act by Constantine (see fig. 6.1).

6.1: The Papal States at their greatest extent, 1513.

6.2: Europe, ca. 1530, Showing the Papal States in darker shading.

On July 28 Stephen solemnly anointed Pepin, his wife, and his sons, putting the final seal of approval on the dynasty and proclaiming to all its legitimacy in the eyes of the church and of God. He bestowed on the king and his sons the exalted title “patrician of the Romans,” a title formerly held by the exarch. Besides being an honor, the title seemed to make this Germanic king a Roman, which was the beginning of a lot of confusion for centuries.

Pepin tried to negotiate with Aistulf to hand over the territories he had promised the pope, but, not surprisingly, Aistulf refused. In a swift campaign Pepin invaded Italy and by August that same year, 754, had defeated Aistulf and forced him to comply. The pope, who had accompanied Pepin’s army, returned to Rome after the campaign and received a jubilant welcome. Stephen had accomplished the impossible.

The celebration was, however, premature. When Pepin withdrew, Aistulf repudiated his agreement and in 756 laid siege to Rome. Stephen was forced to appeal to Pepin who, though unwilling to cross into Italy again, finally acceded to the pope’s repeated entreaties. He met Aistulf’s forces and defeated them. This time there was no immediate Lombard resurgence, partly because of the crushing nature of Pepin’s victory and partly because Aistulf died shortly afterward, leaving no heir.

Stephen moved into the vacuum and successfully backed Desiderius of Tuscany for the Lombard throne, a gesture of support that Desiderius repaid by promising the pope several more cities, including Bologna, for his growing dominions. It was easier, however, to lay a claim to all these territories than to rule them successfully or even to hold onto them, as Leo’s successor found out. When Stephen died in 757, his younger brother Paul was elected. Paul immediately, though only briefly, had to deal with an anti-pope, elected by a group of clergy unhappy with the Frankish alliance. Before he was consecrated, Paul announced his election to Pepin and used the same protocol traditionally reserved for informing the imperial exarch.

It was obvious Paul intended to follow in the path so brilliantly laid out by his brother. He had been Stephen’s trusted adviser and right-hand man, but he did not enjoy Stephen’s good fortune. Desiderius soon made it clear that he did not feel bound by the promises made to Stephen, and he set about trying to recover lands Pepin had donated to Saint Peter. Paul had to beg Pepin to intervene once more, but the king of the Franks, though willing to bring pressure to bear on Desiderius, did not cross the Alps himself or send troops. Both Desiderius and Paul had to compromise, an uneasy peace.

Meanwhile Emperor Constantine V, shocked that lands he considered his own had fallen into the hands of the pope, posed a menace as he tried to forge alliances with both the Lombards and the Franks. He continued the iconoclast policy initiated by Emperor Leo III, which drove more Greek-speaking refugees into Rome and confirmed once again Western perceptions of the emperors as enemies of orthodox faith. Constantine tried to sway Pepin and his bishops to his iconoclast policy, but the Franks resisted, to the great relief of the pope.

When Paul died in 767 after a reign of ten years, twice as long as his brother’s, a surface calm prevailed. Rome was secure enough to allow the pope, following the example of Gregory the Great, to turn his family palace into a monastery for the benefit of refugee Greek monks, near which he built a new church, San Silvestro in Capite. But the situation in central Italy was unstable, made worse by resentment of Paul’s harsh rule. Six or seven centuries after Paul’s death his name began to appear on lists of saints. It still appears there today, though why he merits the honor has never been clear.