7

Charlemagne: Savior or Master?

The year is 800. Picture Saint Peter’s basilica during mass on Christmas Day. At a certain point Pope Leo III takes a crown in his hands and places it on the head of Charlemagne, Pepin’s son and the king of the Franks. This crown does not signify mere kingship but the imperial dignity, an interpretation confirmed immediately when the congregation, obviously prepared for what happened, broke into words reserved for the emperor, singing three times, “Charles, most pious, Augustus, crowned by God, great and peace-loving emperor, long-life and victory!” According to accounts from Charlemagne’s court, the pope kissed the ground in front of him, a gesture reserved for the emperor. Papal accounts omit that important detail but noted, instead, that Leo anointed Charlemagne and called him his “excellent son.”

Everything in the scene is unprecedented. A pope crowns an emperor, having seemingly determined who that emperor was to be. The new emperor is not from old Latin or Greek stock but is a Frank—that is, a German, from a race formerly referred to as barbarian. Moreover, a presumably legitimate emperor—rather, empress (Irene)—is sitting on the throne in Constantinople. She was not consulted or even informed until after the fact. When the imperial court at Constantinople learned about what had happened, it was stupefied.

Aside from an inner circle, therefore, Leo’s contemporaries were altogether unprepared for what took place. The Frankish court tried to pass off the story that even Charlemagne was taken by surprise (see fig. 7.1). Although Leo’s action was far from an inevitable culmination of events that began with Pope Stephen’s meeting with Pepin, it obviously developed out of the close relationship Stephen had established with the king of the Franks. The implications of that relationship became ever clearer as the years passed after the death of Pope Paul, Stephen’s brother.

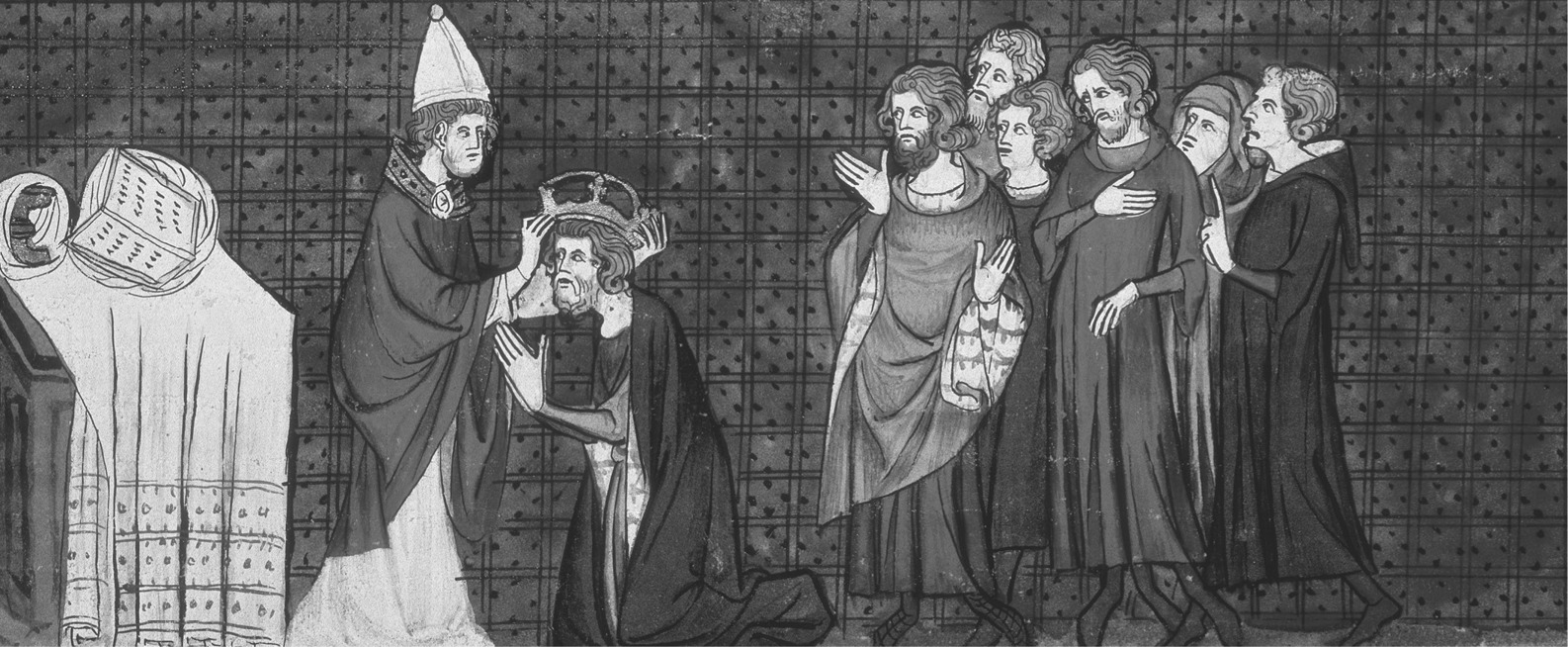

7.1: Charlemagne’s coronation

Charlemagne crowned as emperor, c 1325–c1350. From “Chroniques de France ou de Saint Denis.” Roy 16 G VI. Folio No: 141v. British Library, London, Great Britain.

©HIP/Art Resource, NY

Even as Paul lay dying, Duke Toto (or Theodore) of Nepi was plotting to manipulate affairs so as to make his brother Constantine pope. Constantine was a layman. Especially with the great lands the papacy now claimed, the papal office had become even more attractive than before to the unworthy. Immediately upon Paul’s death, Toto with his three brothers seized the moment. They arranged for armed contingents to enter Rome, take possession of the Lateran, and there have Constantine acclaimed pope, after which he was hastily ordained subdeacon, deacon, priest, and, finally, bishop. The new pope informed Pepin of his election but never received a reply, probably because the king was busy conducting a campaign in Aquitaine but also possibly because he learned of the strange circumstances of the election.

The “election,” in which the clergy played little or no part, was engineered by laymen for their own benefit. The clerical party in Rome regrouped around its leader, Christopher, chief notary of the city, the only important figure openly to oppose Constantine. Christopher with his son Sergius fled the city. They made their way to Pavia to appeal to Desiderius, the Lombard king, to set things right. The appeal could not have fallen on more willing ears. Desiderius was all too happy to settle the matter in a fashion favorable to himself. Lombard troops accompanied by Christopher and Sergius swooped into the city. In the ensuing confusion Toto was killed in street fighting and Constantine seized in the Lateran palace and arrested. He had been pope for a year. He was later officially deposed by a Roman synod, paraded through the streets of Rome on the back of an ass, and imprisoned in a monastery. Many of his supporters were executed. During his imprisonment a gang attacked him and gouged out his eyes

Meanwhile, Christopher helped organize a legitimate election, at which on August 7, 768, Pope Stephen III, Christopher’s candidate, was chosen. Sergius headed an embassy to the Frankish court, where Pepin’s two sons, who were now co-rulers—Carloman and Charles (Charlemagne)—agreed to send a delegation of thirteen bishops to Rome for a synod to mop things up after the great confusion. This synod, held on the day after Easter 769, besides condemning the anti-pope Constantine, decreed that henceforth only the Roman clergy would elect the pope, a decision that outraged the Roman aristocracy and that, as the following centuries showed, they did not observe.

Stephen was pope, but Christopher and Sergius were the power. Unfortunately those two had earned the fierce enmity of Desiderius, who had gained nothing from responding to Christopher’s plea. By a strange turn of fate, moreover, the Franks and the Lombards entered into an era of good feeling, which raised questions about how committed the Franks were to holding the line against Desiderius’s encroachments on the lands given by Pepin. Stephen vacillated in his policies and, chafing under Christopher’s domination, in 771 found an opportunity to betray him and his son to Desiderius and thus send them to their certain deaths. When Stephen, neither loved nor respected, died the next year, the situation in Rome and central Italy was dangerous.

The right man appeared on the scene. In striking contrast to the chaos that broke out upon Paul I’s death, Hadrian, a deacon under both Paul and Stephen III, was in 772 elected easily and without notable opposition. He would have a long reign of twenty-two years (772–795). The major problem facing him, of course, was the tangled and dangerous relationship with Desiderius, now further complicated by the death of Carloman and the dispute over the succession to the Frankish throne. The nobles rallied around Charlemagne, but Carloman’s widow appealed to Desiderius for help. Hadrian was, however, not at all keen on furthering the designs of a house that lately had seemed to draw back from the commitments made by Pepin.

When in the winter of 772–773 Desiderius marched on Rome and was held back only by Hadrian’s threat to excommunicate him (the first time excommunication was ever used for a political goal), Hadrian secretly appealed to Charlemagne for help. Charlemagne, now secure in his brother’s succession, responded favorably and tried to persuade Desiderius to abide by earlier determinations. The failure of those negotiations provided Charlemagne with the excuse he had probably been waiting for. He invaded Italy and by the next spring had captured the Lombard capital, Pavia. With this expedition Charlemagne destroyed the Lombard kingdom once and for all.

He decided to visit Rome for the Easter celebrations, during which he and Hadrian met for the first time. To show his deference for Saint Peter, Charlemagne kissed every step at the entrance to the basilica, inside which the pope awaited him. It was a fateful moment, the beginning of a long personal friendship that had its difficult moments but that in the long run served both men well. In Saint Peter’s on April 6, 774, Charlemagne signed a document that not only confirmed everything in Pepin’s original Donation but added to it vast territories formerly held by the Lombard king. Hadrian’s understanding of the significance of what happened is revealed in the fact that he now began to have coins struck with his own effigy on them, rather than the emperor’s, and to date them accordingly, that is, according to the years of his pontificate. In Hadrian’s mind there was no doubt that he was a king in his own right.

Once Charlemagne mopped up his campaign against Desiderius a few months later, he thought better of his open-handedness and, with Desiderius his prisoner, not only took for himself the title of King of the Lombards but held onto Lombard territory included in his donation to Hadrian. Nonetheless, Hadrian, who was in no position to protest, still ended up a winner, and he knew it. Charlemagne made two more visits to Rome during Hadrian’s lifetime, the occasions of further and reasonably amicable negotiations.

The two men worked especially well together in Charlemagne’s campaign to reform and bring order to the Frankish church. For both men this meant in large part making it conform to canonical standards and liturgical usages that prevailed in Rome. Hadrian sent Charlemagne an important collection of canon law, biased of course toward papal claims of primacy, and also a sacramentary, a book containing the prayers and rubrics for mass, which helped standardize Frankish liturgical practice. The net result was a Frankish church more Roman than before.

In Rome itself Hadrian built, restored, or embellished a number of churches. He repaired the city walls and completely rebuilt four great aqueducts. Under him, with Charlemagne’s help the city enjoyed a peace and prosperity it had not known for a long time. In keeping with the long-standing tradition of special care the papacy felt for the poor of the city, Hadrian established a system whereby a hundred people were fed daily, and he provided resources for other institutions dedicated to the same aim.

On one religious issue Hadrian and Charlemagne or his court had a misunderstanding. In 780 emperor Leo IV died and was succeeded by his young son, which meant a regency under Leo’s widow, the empress Irene. The empress was a determined enemy of the iconoclasts. She besought Hadrian’s cooperation in convoking a council at Nicaea to assert the legitimacy and praiseworthiness of image veneration. Hadrian responded enthusiastically. He did not object, please note, to the fact that a woman called the council.

Nicaea II met in 787, reaffirmed the traditional practice and teaching, and in its decree on the subject incorporated a document drawn up with much care by Hadrian’s curia in preparation for the council. The council marked a rare moment of accord between East and West during these centuries. Charlemagne was insulted that he had not been invited to send bishops to the council. When Hadrian sent him a poor Latin translation of the council’s decrees, Charlemagne and members of his court were dismayed when, because of the faulty Latin of the text, they came to the conclusion that a council had ratified image worship instead of image veneration. But even this misunderstanding did not seriously damage Charlemagne’s relationship with the pope, at whose death in 795 he was said to grieve as if he had lost a brother or a child.

Leo III, a priest of humble origin who had risen high in ecclesiastical rank, was elected pope the day Hadrian died and consecrated bishop the next day. The speed with which these events took place suggests a carefully planned preemptive strike by his supporters against other contenders. What is certain is that from the beginning Leo had enemies among the Roman aristocracy who were determined to unseat him. It is ironic, therefore, that, like Hadrian before him, he had an unusually long pontificate that lasted almost twenty-one years, 795–816.

He sent word of his election to Charlemagne along with the keys to Saint Peter’s tomb and the banner of Rome, seemingly sensing at this early date that he would need the protection of the king of the Franks. Charlemagne replied politely but let the pope know that the papal office was strictly spiritual, whose essential duty was not much more than praying for the good of the church and for its protector, himself. “Your task, Holy Father, is to raise your arms to God in prayer as Moses did to ensure the victory of our arms.” Many subsequent emperors (and kings) subscribed to this understanding of the pope’s role in the church.

Four years later, on April 25, 799, Leo’s enemies staged a vicious coup against him. While the pope was leading a procession through the streets of Rome on the way to Saint Peter’s, a gang led by a nephew of Pope Hadrian attacked him, threw him from his horse, beat him, and attempted unsuccessfully to gouge out his eyes and cut out his tongue. Leo somehow lived to tell the tale but then was accused of adultery and perjury, deposed, and imprisoned in a monastery. He managed to escape and make his way to Paderborn to plead his cause with Charlemagne. Not to be outmaneuvered, his enemies sent envoys to the king to justify their actions and to lay out a list of charges against the pope in which the most serious were adultery and perjury.

Charlemagne, advised by the learned monk Alcuin, proceeded cautiously, though his entourage was inclined to believe the accusations. He had Leo conducted back to Rome, protected by guards, where an investigation was carried out by Frankish agents that tended to confirm the major charges. But the matter was again referred to Charlemagne, who decided to come to Rome himself to settle the affair. He arrived in late November 800, and was greeted with great pomp that Leo was able to orchestrate. Charlemagne convoked a meeting of Roman and Frankish bishops, abbots, and notables to review the case once again and then to decide the fate of the pope, but the assembly demurred at the prospect of sitting in judgment on a pope.

At that point Leo volunteered to take a solemn oath to purge himself of the charges, and this was the solution agreed upon. On December 23, in the presence of a large and solemn assembly, Leo swore his oath, whose text survives to this day. The emperor was satisfied. Leo was thus vindicated against his enemies. Two days later the extraordinary event took place in Saint Peter’s that gave the world a new emperor.

From that time forward until Charlemagne’s death in 814, Leo, though secure in his position, knew his place. He acted more as Charlemagne’s agent in Italy than as an independent bishop, let alone as the bishop of Rome. On one crucial point, however, he resisted the emperor’s wishes. The Frankish church had inserted an addition into the venerable and sacrosanct Creed formulated at the first council of Nicaea, 325, and somewhat elaborated upon by the next council, Constantinople I. Not only was such tampering unprecedented, it was also expressly forbidden by the council of Ephesus, 431.

The Creed said simply that the Holy Spirit proceeded “from the Father.” The Franks had added “and from the Son,” the famous filioque that would later cause such contention between the Greek and Latin churches when the West later accepted it into the Creed. The problem was not only the doctrine of the filioque but as well the unilateral and illegitimate insertion into the Creed. When in 809 Charlemagne sent to Leo the opinion of his bishops favoring the filioque, Leo responded sharply and reprimanded the bishops.

Leo, despite his subservience to the emperor he had created and his continued unpopularity with much of the Roman clergy, showed himself an able administrator of the old papal patrimony. He further strengthened the network of assistance to the poor and needy in the city and took the initiative in constructing and restoring churches and in adorning some of them lavishly. He constructed a great hall for the Lateran palace that could be used both for social occasions, like banquets, or as a place to conduct business that required a large assembly.

When Charlemagne died in 814, Leo lost his protector. He at that point discovered a serious conspiracy to assassinate him. By this time, however, he had enough control of the city to rout out the conspirators and bring them to trial. A large number of those found guilty were executed—sources give the almost certainly exaggerated figure of three hundred.

Leo himself did not have long to live. He did not die a beloved pope. The Romans were ready for somebody less harsh and more conciliatory, whom they found in Stephen IV (816–817), a Roman aristocrat. The new pope was firmly devoted to the house of Charlemagne. Almost immediately after his election he made the people of Rome swear allegiance to Louis the Pious, Charlemagne’s son. Shortly thereafter he crossed the Alps to anoint and crown Louis at the cathedral in Rheims. Although neither he nor his predecessor had a voice in who was to succeed Charlemagne, this anointing was important because it gave rise to the conviction that the exercise of full imperial authority was not legitimate without some form of papal recognition.

During his sojourn at Rheims Stephen and Louis held long conversations together. The newly crowned emperor renewed his commitment to defend the Apostolic See and assure canonical elections of the pope. Stephen also won from the new emperor a pardon for the conspirators against Leo III whom Louis’s father had exiled in 800 after the pope vindicated himself by his oath. He returned to Rome laden with lavish gifts from Louis, but he died three months after reaching the city.

Between the pontificate of Stephen II and Stephen IV, a period of some sixty-five years, a politico-ecclesiastical revolution of almost titanic proportions had occurred with ramifications almost beyond counting. Why and how it happened is clear, but one aspect of its ramifications requires comment: the popes’ easy acceptance of responsibility for the vast territories included in Pepin’s Donation. Unfortunately, no pope from the era left us a document in which he spelled out the reasons for this remarkable acquiescence. The rationale for it must be patched together through inference and consideration of circumstances.

From the appearance around this time of the Donation of Constantine it can be inferred that, as mentioned, contemporaries of the fateful decision also required justification or explanation. The forgery originated in Rome probably sometime in the mid-eighth century but certainly no later than 850. It purported to be a grant from Constantine to Pope Silvester in which the emperor conferred upon the pope and his successors primacy over all other churches and political dominion not only over Rome but over the entire West. In it Constantine also offered the pope the imperial crown, which he humbly refused. Later popes used the document to validate some of their claims and, although doubts about the Donation’s authenticity were sometimes expressed, it was not definitively unmasked as a forgery until the fifteenth century.

Unquestionably among the reasons that prompted Stephen II to accept Pepin’s gift with so much enthusiasm was that it promised to give the papacy resources to deal with the Lombard threat, resources that were vastly increased by the promises Charlemagne later made as he dismantled the Lombard kingdom. The popes saw what developed into the Papal States as a line of defense for the city of Rome itself, a buffer state that could absorb the shock of aggression against it.

The popes surely also saw their role over the new territories as consonant with their traditional oversight of the extensive and scattered lands of the old papal patrimony. From that perspective the new situation was just more of the same—lots more! Just as the patrimony provided revenues to allow the popes to fulfill their many and seemingly ever expanding responsibilities, so would these new lands.

Not to be discounted, finally, is a persuasion made explicit by a few later popes that Saint Peter was pleased to be in charge through his vicar of an earthly kingdom. That is a mentality so far removed from the twenty-first century that it is difficult to take it seriously, but the evidence for it is clear. One thing is absolutely certain: the popes came to look upon the Papal States as a sacred trust which, along with ambition and greed, explains why they clung to them for the next millennium with such uncompromising tenacity.