13

Boniface VIII: Big Claims, Big Humiliation

By the end of the century that opened so propitiously with Innocent III, the papacy was about to enter two extremely difficult and scandalous periods, the so-called Babylonian Captivity, which segued into the Great Western Schism. The vestibule to those periods was the back-to-back pontificates of Celestine V and Boniface VIII. In his Divine Comedy Dante, who was the popes’ contemporary, placed both of them in hell.

After Innocent III a series of capable and spiritually minded popes followed, all of whose pontificates were severely troubled by conflicts with Emperor Frederick II, who was determined to establish himself in Sicily and in southern and central Italy. Matters reached a climax when in 1244 Innocent IV secretly fled Rome to France. The next year he convoked the First Council of Lyons, whose agenda was broad but whose center was Frederick. The council summoned Frederick to answer charges of perjury, breach of the peace, sacrilege, and heresy. The emperor did not appear but was allowed a defense attorney who, not surprisingly, was unsuccessful for his client.

The council deposed Frederick, released his vassals from their oaths of fealty, and invited the Germans to elect a new king. Although somewhat weakened by the council’s action, Frederick was able to defy it. Only his unexpected death five years later resolved the conflict. It was the end of a long era. Frederick was the last of the emperors to inflict such havoc upon the papacy, which now had to begin contending, instead, with other rulers.

Despite the disruptions Frederick caused in the first half of the century, the popes managed to function and, under the circumstances, function well. They continued to give support to the Dominicans and Franciscans and encouraged the development of similar orders, such as the Augustinians and the Carmelites. They also fostered the development of lay associates of these orders, the “tertiaries” (a third level of membership after the friars and the nuns), which was extremely important for the spread of a deeper piety among the laity and would produce a number of saints, including Saint Catherine of Siena. Even after the disaster of the Fourth Crusade, they in this period launched three more, with the usual frustrating results. They tried to stamp out the vestiges of the Albigensian heresy that still persisted. They supported the universities, now fully mature institutions, and they were especially instrumental in fostering the development of canon law.

Meanwhile, as the empire declined after the death of Frederick, the French monarchy grew ever stronger. In 1262–1263 Charles, count of Anjou, ambitious brother of the saintly Louis IX, moved into southern Italy at the invitation of Pope Urban IV, himself a Frenchman, to establish an Angevin kingdom there (Angevin meaning “from Anjou”). His presence near Rome divided the cardinals into pro-French and anti-French camps, a division further exacerbated by rivalries among the great Roman families, especially the Orsini and the Colonna.

Although the caliber of popes continued generally high, the second half of the century saw thirteen popes in forty-four years, an average of three years per pontificate. Practically all were elected outside Rome—at Viterbo, Perugia, Arezzo, Naples—either because of a particular political situation or because Rome was deemed too unhealthy for a lengthy meeting. There were often delays of many months, even years, between the death of one pope and the election of another.

After the death of Clement IV in 1268, for instance, the cardinals who assembled at Viterbo took three years to elect a successor, Gregory X. As public resentment against them mounted, the civic authorities of Viterbo finally locked them in the papal palace, then removed the roof, and finally threatened to cut off their food supply if they did not come to a decision. The learned and devout Gregory, not a cardinal and elected in absentia, was as scandalized as everybody else by the long interregnum and as pope decreed that henceforth the cardinals would be sequestered until they elected a pope and suffer a carefully calculated reduction of food and drink as the deliberations dragged on. Although the cardinals had been put under lock and key for the first time at the election in 1241, Gregory’s decree is conventionally considered the origin of the papal “conclave” (con clave, “with a key”). Gregory’s provisions were observed loosely, intermittently, or not at all in subsequent papal elections, but they put on the books a basic procedure still operative today for papal elections.

By the end of the century the prestige of the papacy had declined from the high level achieved by Innocent III. The popes’ constant involvement in political and military conflicts took its toll on their reputations, even though they often, given the assumptions of the age, could hardly have stayed aloof from them. They faced growing criticism because of levies they imposed for financing crusades and for other causes and faced it as well for what sometimes seemed the ostentatious wealth of churchmen, especially the cardinals and the pope himself. A radical branch of the Franciscan order, the “Spirituals,” preached a poverty for the church and the papacy that sounded suspiciously like destitution and especially on this issue they became dangerous antipapal propagandists. Even outside Franciscan circles expectations that God was about to send an “angel pope” to rescue the church from worldliness circulated fairly widely

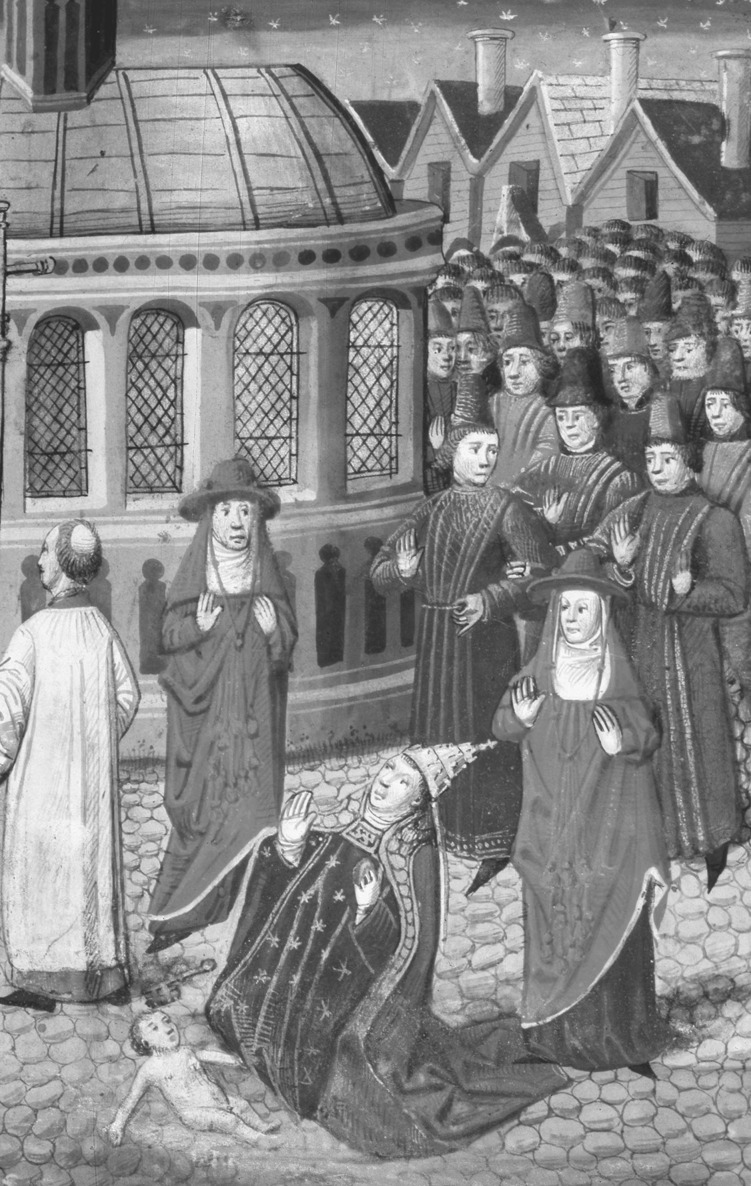

This was the sour context in which the legend of Pope Joan emerged. According to the story, which, though it has absolutely no basis in fact, was accepted as true in the Middle Ages and later, a learned woman in male disguise managed to get herself elected pope. She reigned for two years. During a procession on its way to the Lateran Joan gave birth to a child, which in the most dramatic fashion imaginable unmasked the deception. She died immediately afterward. Versions differed of course in detail, including the years when Joan reigned, though it was never set in the present or near-present. What the legend indicated was how ready the faithful were to believe the worst (see fig. 13.1).

13.1: Pope Joan

Pope Joan giving birth to a child during a procession. Des Clercs et Nobles Femmes, by Giovanni Boccaccio. Ms.33, 69 verso. Vellum. France, c.1470. Spencer Collection. Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

© The New York Public Library / Art Resource, NY

When Nicholas IV died at the end of the century, 1292, the twelve cardinals—ten Italians and two Frenchmen—were hopelessly divided, split this time as much by personal and family rivalries as anything else. They took twenty-seven months to elect a new pope. The conclave (such as it was) first met in Rome, then transferred to Perugia, and then back to Rome, where the bickering continued. When Charles II, the Angevin king of Naples and Sicily, arrived there in March 1294, he applied pressure for a resolution of the impasse, but even that expedient did not work. After the king’s departure the meeting, again transferred to Perugia, dragged on into July.

The king meanwhile urged a hermit, Pietro del Morone, to write to the cardinals, warning them that dire calamities would befall the church if they delayed any longer. The letter had an impact and moved the cardinals to elect no other than the letter’s author, a complete outsider to the conclave and a complete outsider to organized ecclesiastical life. The new pope-elect, startled by this turn of events, was only with difficulty persuaded to accept the cardinals’ decision. He took the name Celestine V. He was in his mid-eighties.

Pietro del Morone had as a much younger man organized a small brotherhood of hermits and gained a reputation for holiness. Although an ordained priest, he had only a rudimentary education and could barely read Latin. The Spiritual Franciscans greeted his election with jubilation, expecting him to be a pope who would put things aright according to their radical program. Here was a pope who stood for poverty, austerity, and holy simplicity.

Celestine’s election broke the deadlock in the conclave, and the cardinals could congratulate themselves on choosing somebody who had no worldly attainments, a purely spiritual candidate. They had risen above all pettiness, they believed, and made a holy choice. After the election and coronation, Charles II made himself Celestine’s guardian and installed him in his capital in Naples, to the great dismay of the cardinals who had elected him. Celestine took his orders from Charles, appointed Charles’ favorites to key positions in the curia and Papal States, and created twelve cardinals who were Charles’s nominees. On his own, however, he showered privileges on his congregation of hermits and showed similar favors to the Spiritual Franciscans.

It soon became obvious to everybody close to him that Celestine had not the slightest idea of what was expected of him and that he lacked every skill required by the highly responsible position to which he had been elected. His ignorance of Latin was simply his most obvious deficiency. Soon even he realized that a mistake had been made. On December 13, 1294, after a pontificate of five months during which he never set foot in Rome, he abdicated. In the presence of the cardinals he read his statement, laid aside his pontifical robes, and donned once again his gray habit as hermit. He was now once again simply Pietro del Morone. As a contemporary chronicle put in, “On Saint Lucy’s day, Pope Celestine resigned, and he did well.”

Eleven days later, on Christmas Eve, the cardinals assembled in Naples and elected one of their number, Benedetto Caetani, who took the name Boniface VIII. It is not clear what led to such swift action, in striking contrast to the previous conclave. The cardinals’ choice, in any case, fell on a man who could not have been more different from his predecessor. Boniface came from a family of the minor aristocracy located in the countryside south of Rome near Anagni. As a young man he studied law at Bologna and elsewhere, now almost the prerequisite for rising in secular or ecclesiastical ranks. He soon made his mark in the papal curia and gained international experience by accompanying legates to both France and England. His intelligence, his firm grasp of canon law, and his practical skills won him attention and respect, which meant he was entrusted with more and more assignments. In Paris in 1290, for instance, he settled the conflict between the religious (Franciscan and Dominican) and the diocesan clergy with dispatch and skill, but his abrasive and arrogant manner made him unwelcome ever to return. Through the accumulation of benefices he became one of the wealthiest cardinals, a step along the way toward fulfilling his ambition of putting his family on the same footing with the old Roman nobility such as the Orsini and Colonna.

From the outset his pontificate was bedeviled with questions about the legitimacy of Celestine’s abdication. Was it legal for a pope to resign? In Celestine’s favor it must be said that he consulted canonists before taking the step, but in Boniface’s disfavor it must be said that he was among those consulted. This was a fact that would be thrown up against him and then distorted into a nefarious intrigue, as if he deceived the pope into taking the fateful step. Although there is no evidence that Boniface with malice aforethought misled Celestine, the allegation was plausible and spread among the pope’s many enemies. Dante, who did not question the legality of Celestine’s action, put him in hell for cowardice, for ducking the responsibility to which he was called (Inferno, 3.58–3.61).

One of Boniface’s first acts was to rescind or suspend many of the decrees of his predecessor and to dismiss many of the officials he installed. For obvious reasons, Boniface kept a careful eye on Celestine, who at first moved around with perfect liberty. He became more concerned about him as an unwitting tool of his enemies and within a year had him locked up in the Castel of Fumone about forty miles south of Rome, where the aged pope soon died of natural causes. Rumors spread that Boniface had him murdered. Among Boniface’s enemies the Spiritual Franciscans had an international network of monasteries that transmitted the rumors and allegations. Not only were they dismayed at Celestine’s resignation, but they saw in Boniface the epitome of all they hated. Boniface meanwhile annulled most of the privileges Celestine had granted them.

The two cardinals from the Colonna family had voted for Boniface in the conclave, but they became increasingly critical of his high-handed behavior. They soon clashed with him over aspects of his international policy and, more specifically, over the expansion of the estates of the Caetani family in territory they considered their own outside of Rome. They joined in the campaign of rumors against him, which included the murder of Celestine. In May, 1297, Stefano Colonna, a brother of Cardinal Pietro Colonna and nephew of Cardinal Giacomo Colonna, highjacked a convoy of treasure on its way from Anagni to Rome. That action set off a series of confrontations between the pope and the family.

The cardinals agreed to return the money but refused to deliver up their relative to justice. They meanwhile intensified the campaign questioning Celestine’s resignation and called for a council to adjudicate the matter. Things went from bad to worse, with Boniface first stripping all ecclesiastics in the family of their honors and benefices and then finally sending a military force against the Colonna that razed their fortresses and seized their stronghold in Palestrina. The cardinals fled to France, to the court of King Philip IV, known as Philip the Fair, who was himself in conflict with Boniface and not inclined to yield him an inch. The king was the grandson of Saint Louis IX but was as calculating and ruthless as his grandfather had been temperate and generous. All the pieces were now in motion for a collision of momentous proportions.

The dispute between the pope and the king arose over a clear-cut issue—the right of the king to tax the clergy. Lateran Council IV had decreed that such taxation imposed unilaterally was illegal. Boniface tried to enforce the legislation. In the first instance of his clash with Philip, 1296, he had to back down when Philip retaliated by forbidding the export of revenues of the French church to the papal treasury, upon which Boniface relied heavily. As a sign of his good will, in 1297 Boniface canonized Philip’s grandfather, Louis IX.

In 1300 Boniface declared a year of jubilee to celebrate the anniversary of the Savior’s birth, the first such jubilee in the history of the church. This event, highly successful, established a pattern for many other Holy Years to follow. Even as the pilgrims flocked to Rome, Boniface heard news of further encroachments of Philip on “the liberty of the church,” which climaxed two years later when the king arrested a French bishop, put him on trial in his own presence on the usual charges of blasphemy, heresy, and treason, and then had him thrown into prison. The king’s action was a flagrant violation of canon law, which stipulated that a bishop could be tried only by the pope. Angry exchanges between the two parties ensued. Boniface ordered the French bishops to come to Rome for consultation and, though Philip refused them permission to leave the kingdom, almost half of them appeared.

With that, in November 1302, Boniface issued the bull Unam Sanctam, one of the most famous documents in the history of the papacy. Without naming Philip, it was of course directed against him and his policies and especially against the French bishops who obeyed the king’s command rather than the pope’s. In essence the document was an assertion of the traditional doctrine of the superiority of the spiritual authority over the temporal. But its language was particularly strong and its famous final assertion categorical: “Therefore, we declare, state, define, and pronounce that it is absolutely necessary to salvation for every human creature to be subject to the Roman Pontiff.”

Canonists and theologians have debated the interpretation of that assertion ever since, but Philip had no doubt what it was—a declaration of war. The king had no interest in replying except by force. In June 1303 he called together an assembly to hear charges against the pope that went on for pages. For instance:

He does not believe in an eternal life to come . . . . and he was not ashamed to declare that he would rather be a dog or an ass or any brute animal than a Frenchman. . . . He is reported to say that fornication is not a sin any more than rubbing the hands together is. . . . He has had silver images of himself erected in churches to perpetuate his damnable memory, so leading men into idolatry. . . . He has a private demon whose advice he takes in all matters. . . . He is guilty of the crime of sodomy. . . . He has caused many clerics to be murdered in his presence, rejoicing in their deaths. . . . He is openly accused of the crime of simony. . . . He is publicly accused of treating inhumanly his predecessor, Celestine, a man of holy memory and holy life who perhaps did not know that he could not resign . . . and of imprisoning him in a dungeon and causing him to die there swiftly and secretly.

Meanwhile the king had dispatched to Italy two agents to gather a force to seize the pope and bring him to Paris to stand trial for his crimes. One of the agents was Guillaume de Nogaret, the king’s chief minister, and the second was Sciarra Colonna, another brother of Cardinal Pietro Colonna. Boniface had meanwhile left Rome for his family home at Anagni where he prepared a bull excommunicating the king. While he was there a band of several hundred mercenaries under the leadership of de Nogaret and Colonna arrived at Anagni. It broke into the palace and into Boniface’s quarters. The pope was awaiting them in full pontifical robes and challenged them to lay a hand on him, shouting, “Here is my head! Here is my neck!” Colonna wanted to kill the pope on the spot, but de Nogaret disagreed. As the leaders quarreled through the following day about the fate of their prisoner, the whole district was aroused against the invaders. The locals were finally able to rescue the pope and put his enemies to flight. Dante, no friend of Boniface, was horrified at what became known as the outrage at Anagni (Purgatorio, 20.85–20.90). Boniface returned to Rome a broken man and died there a short while later. Although Philip was deprived of the satisfaction of putting the pope on trial, he had otherwise triumphed over him and shown for all the world to see the practical limits of Boniface’s claims. The papacy was again in full crisis, this time not because of an emperor but because of a king of France, whose mischief-making had by no means ended.