Part One

Introduction

New Characters:

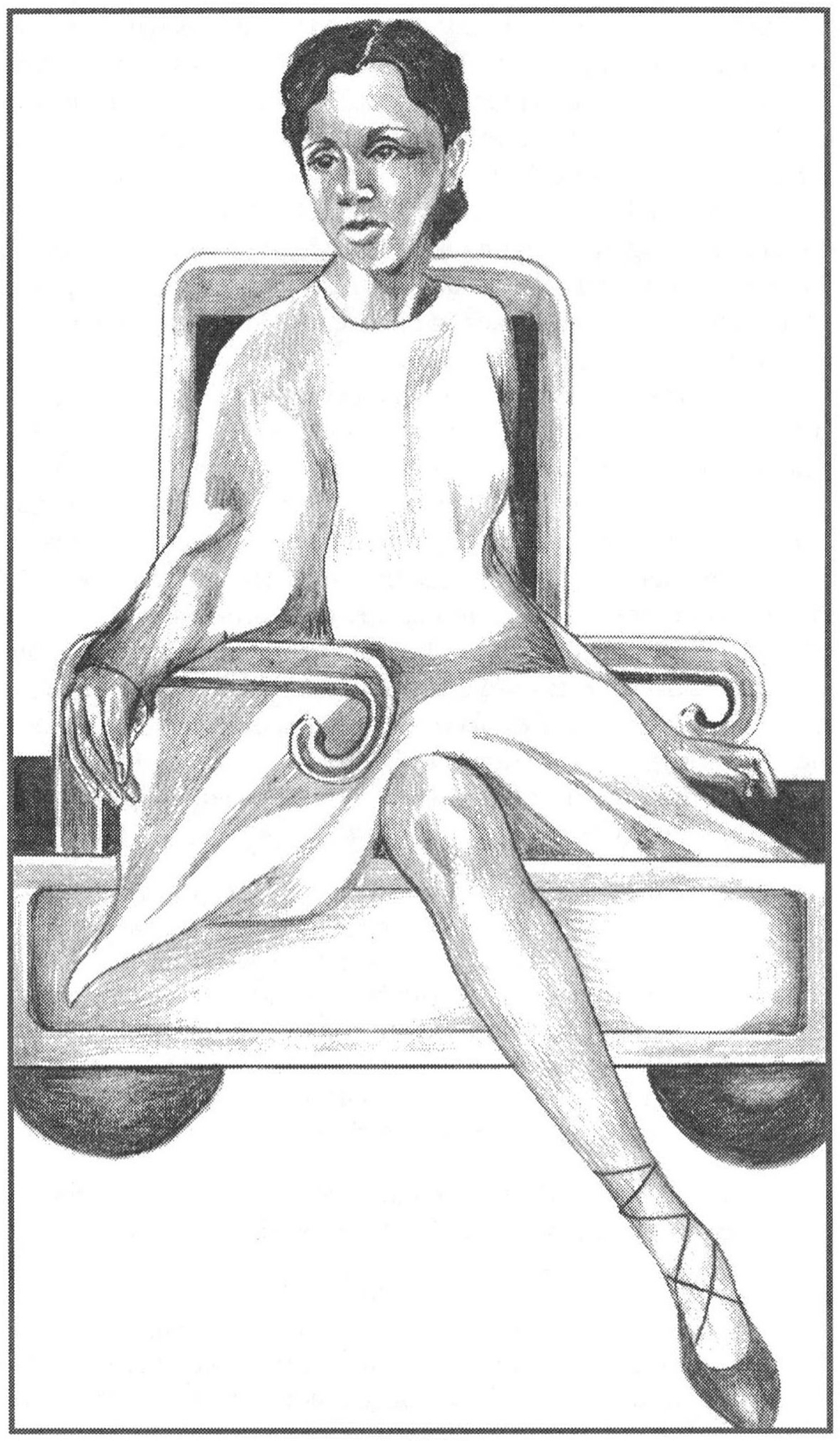

Sula Peace: a little girl who grows into a woman in the Bottom

Inhabitants of the Bottom: black people who live in the hills and are dissatisfied with their lots

Inhabitants of the valley: white people who live in the valley

Slave owner: man who gives his slave a chore with the promise of both freedom and a parcel of land upon successful completion; talks the slave into taking hill land instead; says that the hill land is the bottom of Heaven

Slave: performs the chores given to him and accepts the Bottom parcel of land

Summary

The Medallion City Golf Course and the suburbs were replacing beech trees, the blossoming pear trees with children in their branches, the Time and a Half Pool Hall, Irene’s Palace of Cosmetology, Reba’s Grill, and the old neighborhood.

The white people lived in the rich valley because of a slave owner’s trickery. The slave owner promised his slave a parcel of land and freedom if he performed some difficult tasks. After accomplishing the tasks, the slave was given his freedom, but the owner was reluctant to give him a parcel of land. Instead, the owner tried to outwit the worker by telling him that the hills were the bottom of Heaven. The ex-slave innocently asked for the Bottom, and the owner gave him the land. Since that time the ex-slave and, later, his descendants, had to work hard on hilly land. Plowing was difficult. Soil and seeds washed away. The wind blew.

Later, the white people in the valley decided that they liked the hills, the view, and the sounds of laughter, banjos, and song they heard coming from the Bottom. A visitor to the hills might see a woman dancing to the music from a mouth organ and the watchers laughing. Such a stranger might question if the slave owner had been right in his verbal appraisal of the hills. A hunter might wonder if the Bottom were not better than the valley. Even though the residents of the Bottom had little time to consider it, they would quickly respond that the valley was better.

Analysis

The theme of discontent with one’s lot in life is obvious throughout the chapter. The hilly land becomes the reward for the ex-slave; the worker trustingly accepts the word of the farmer that the hills are superior to the valley. The hill residents soon become disillusioned with the acreage that they have accepted and envy the land of the valley residents. On the other hand, the inhabitants of the low lands often view with envy the neighborhood that they can see and hear above them.

Pronounced change is assaulting Medallion. The Bottom in particular, the narrator tells us, is changing quite rapidly. The Medallion City Golf Course and the suburbs are replacing the woods and the buildings in the old neighborhood. The residents of the Bottom, however, remain innocent and totally unaware of the value of what they possess. Even the threat of losing what they own does not bring an awareness to the hill residents. The result of the change is lost on the innocent hill residents.

It is evident that the setting is integral to the plot; it also serves to illuminate the characters and clarify the conflict. The setting suggests the idea of Heaven and Hell. The Bottom does indeed resemble Heaven, the residents look down on the white people below, and the innocence of the people suggests their goodness. The inhabitants of the Bottom, however, often ignore the beauty and their good fortune to be there.

Innocence is a major theme in this chapter. The slave trustingly accepts the story of his owner about the Bottom. The slave owner takes advantage of the naiveté of the slave and uses the slave’s trusting nature to his own advantage. He has deliberately used deceit. The residents of the Bottom are also innocent in that they do not realize the value of their land and their culture.

It is at this point that Sula departs from the stories one usually reads. There are no rewards for the goodness and innocence of the slave; there is no punishment evident for the evil acts of the slave owner. The separation of the whites and the blacks continues over several generations, and both parties maintain their discontent.

The slaves and their descendants seem unaware of the value of their possessions; they desire the valley. The valley dwellers continue to be greedy and cling to what they have—while wanting what the Bottom dwellers have also. Every indication is that the valley residents will take over the hill land and displace the residents there without any punishment for their greed and deceit.

It is significant that both good and evil are in the story. The blacks on the hilly land accept the fact that both right and wrong exist, but they do not try to change things. Even when the townspeople of Medallion, Ohio, spread their golf course and suburbs into the Bottom and raze, or tear down, the buildings there, the inhabitants of the Bottom do not protest. These hill inhabitants see evil merely as something that they must withstand or bear and not as something they must eliminate or change. Retaliation for wrongs inflicted on them or on their ancestors is something that the hill residents do not consider. They do not demand rewards for their tenacity or punishment for the wicked.

The characters in the chapter are flat characters. Morrison does not try to make them complete to the reader by revealing their thoughts, their actions, their speech, or their personal history. Rather Morrison presents them as a stereotypical slave owner with only his own interests at heart and a slave, who is innocent and often misled by one who pretends to have his best interests at heart. The stereotypical view of the easily-duped slave seems to persist into the twentieth century with the innocent Bottom residents.

Morrison makes use of many stylistic devices in depicting the Bottom. Alliteration is evident in “...a bit of cakewalk, a bit of black bottom, a bit of ‘messing around’....” She effectively uses contrasts: white vs. black, hills vs. valley, slave owner vs. slave, trickster vs. tricked, innocent vs. guilty. Personification pictures fingers which dance on the wood and kiss skin. Very descriptive language allows the reader to see both the streets of Medallion which were “hot and dusty with progress” and the heavy trees sheltering the shacks in the Bottom.

Morrison does not use a simple chronological order for the plot of this chapter—or for the entire book. Rather she weaves the plot through the use of foreshadowing, flashbacks, and chronological development. The plot spirals, doubles back, and skips forward. Such plot development allows the narrator much leeway in telling the story and makes it necessary for the readers to attend carefully to the detail to ensure that they receive all the information correctly.

With such an eclectic order in the plot, the writer can leave the reader hanging and answer the questions at a later point in the narrative; the writer does not have to systematically answer the posed questions in chronological order. Waiting for the answers creates suspense for the reader.

Unanswered questions at the end of the introduction entice the reader to continue the book. The unanswered questions in this first part of Sula include what Shadrack is all about, what Sula is all about, and who the black people really are. It is evident, then, that Sula is not episodic. Rather, Sula is a suspenseful novel which requires the reader to complete the entire book to answer all the questions.

Study Questions

- What was the name of the town near the Bottom?

- Where was the town?

- What grew on the Bottom before the spread of the town?

- What were the names of the three businesses that the white townspeople planned to destroy?

- What does the word raze mean?

- What were the two rewards the white slave owner promised the slave for completing the chores?

- What was the name of the hilly land where the black people lived?

- How did the hilly land get its name?

- Who was the little girl introduced in the chapter who grew into a woman in the Bottom?

- What did the white people below think about the hilly land?

Answers

- The name of the town was Medallion.

- The town was in a valley in Ohio.

- Before the spread of the town, trees grew on the Bottom.

- The names of the three businesses that the townspeople planned to destroy were Reba’s Grill, the Time and a Half Pool Hall, and Irene’s Palace of Cosmetology.

- The word raze means to destroy or to level.

- The two rewards the white slave owner promised the slave for completing the chores were freedom and a parcel of land.

- The hilly land where the black people lived was the Bottom.

- The hilly land got its name because the slave owner said that the land was the bottom of Heaven.

- The little girl introduced in the chapter and who grew into a woman in the Bottom is Sula.

- The white people eventually viewed the hilly land as attractive.

Suggested Essay Topics

- Part One stimulates the reader to continue the book by leaving the reader with some unresolved issues. What are three of the unresolved questions at the end of the chapter? Describe each.

- Change is a major theme in this chapter. Cite and describe at least four instances of change in the chapter.

Chapter One: 1919

New Characters:

Shadrack: a young man with a psychological war injury from World War I; founder of National Suicide Day

Male nurse: the balding man who treats Shadrack in the hospital

Reverend Deal: a minister of the Bottom who accepts National Suicide Day

Summary

Every January 3rd after 1920, Shadrack celebrated National Suicide Day. For many years, he was the only one to celebrate. The events of 1917 resulted in his establishment of the holiday.

During World War I, Shadrack, who was barely 20, and his comrades met the enemy on a French field in December of 1917. After seeing his friend killed, Shadrack awoke in a hospital. Even though Shadrack was still hallucinating and violent, the hospital discharged him with $217, his papers, and a full suit of clothes.

Upon his arrival in town, Shadrack’s hallucinations continued. When the police locked him in jail for vagrancy and intoxication, the 22-year-old felt relieved.

After the police officers read Shadrack’s hospital discharge papers with his personal information on them, they returned him to the Bottom on the back of a truck. For 12 days Shadrack struggled to order his thoughts.

On January 3, 1920, Shadrack walked down Carpenter’s Road with a cowbell and a hangman’s rope. The people were wary but listened to what Shadrack had to say. He announced on the Charter National Suicide Day in 1920 that this was the only chance for a year for residents to kill others or themselves. Gradually the annual event became a part of the neighborhood.

Analysis

Morrison uses a limited omniscient style when she takes the reader into the mind of only one character: Shadrack. Her descriptions of Shadrack’s thoughts and feelings enable the reader to see the world through Shadrack’s eyes (Menippean satire). For instance, the narrator describes how Shadrack saw through his tears his own fingers. His fingers seemed to fuse with the fabric of his laces and to move in and out of the eyelets of his shoes.

Morrison also presents the character to the reader through Shadrack’s actions; through the narrator the reader learns that Shadrack sold fish two days a week and “...the rest of the week he was drunk, loud, obscene, funny, and outrageous.”

The reactions of others to Shadrack also reveal his character; for instance, the reader finds that hospital workers bind Shadrack into a straitjacket. Additional information shows the reactions of others to Shadrack after his return from war:

“At first the people in the town were frightened; they knew Shadrack was crazy, but that did not mean that he didn’t have any sense or, even more important, that he had no power.”

The way that others speak to Shadrack shows how they view him; for example, the nurse has no sympathy for Shadrack and asks, “‘Private? We’re not going to have any trouble today, are we? Are we, Private?’”

Shadrack is a dynamic character: one who changes. He is a young boy who enters World War I. When he returns, he is damaged severely from the action on the field in France. Shadrack is also a round character that the reader knows well. After reading the chapter, one knows what Shadrack thinks and feels. For example, “...With extreme care he lifted one arm and was relieved to find his hand attached to his wrist.” One also learns how Shadrack reacts to others; for instance, the reader finds that Shadrack “never touched anybody never fought, never caressed.”

Shadrack’s appearance also helps reveal him to the reader:

“The sheriff looked through the bars at the young man with the matted hair. He had read through his prisoner’s papers and hailed a farmer....In the back of the wagon, supported by sacks of squash and hills of pumpkins, Shadrack began a struggle....”

There is symbolism in the name of the road (Carpenter’s Road). Shadrack walks down Carpenter’s Road when he tries to bring order for himself and others by establishing National Suicide Day. The name of the road reminds the reader of an earlier carpenter who walked down a road before his crucifixion.

The integral setting helps both to illuminate Shadrack to the reader and to clarify the conflicts which are to come. Many communities do not have the social relationships that the people in the hills develop. The story would not work in such a place because others would just ignore the actions of a character like Shadrack. Perhaps the tight-knit town to which Morrison returned after her failed marriage was the model for the Bottom.

There is symbolism also in the name of the character Shadrack. Like the Shadrack in the Old Testament who survived the fiery furnace, this Shadrack, too, withstands his own test of fire. Morrison even notes that the minister acknowledges Shadrack’s walk down Carpenter’s Road and incorporates the event into his own life and sermon.

Morrison shows how innocent the Bottom people are. She shows them readily accepting others and even what life hands them. She also shows them incorporating National Suicide Day into their thoughts, behavior, and lives. Their image perpetuates the myth of the docile slave begun in the introductory chapter.

Morrison makes use of many literary devices. Alliteration is evident when she writes that “He shuffled, grew dizzy, stopped for breath, started again, stumbling and sweating....” A metaphor is evident when Morrison notes that Shadrack “...let his mind slip into whatever cave mouths of memory it chose.” An example of personification is obvious when Morrison indicates that “...the blackness greeted him....”

Study Questions

- What event did Shadrack establish?

- In what year did Shadrack receive his discharge from the hospital?

- What did Shadrack feel the first time he encountered shellfire?

- What were the two possible reasons that the hospital discharged Shadrack?

- What were the charges the police listed for arresting Shadrack?

- What road did Shadrack march down annually?

- What two things did Shadrack carry on his trip down Carpenter’s Road?

- In what year did Shadrack establish the national holiday?

- What appeal did he give to the people of the Bottom each January 3rd?

- What was the reasoning behind Shadrack’s establishment of National Suicide Day?

Answers

- Shadrack established National Suicide Day.

- Shadrack received his discharge from the hospital in 1919.

- Shadrack felt only a tack in his shoe the first time he encountered shellfire.

- The hospital discharged Shadrack because of his violence or another priority, such as the limited number of beds in the hospital.

- The charges the police listed for arresting Shadrack were vagrancy and intoxication.

- Shadrack marched down Carpenter’s Road annually.

- Shadrack carried a hangman’s rope and a cow’s bell on his trip down Carpenter’s Road.

- Shadrack established the national holiday in 1920.

- Each January 3rd, Shadrack told the people this was their only chance to kill others or themselves.

- The reasoning behind Shadrack’s establishment of National Suicide Day was to establish order because Shadrack was afraid of the unexpected.

Chapter Two: 1920

New Characters:

Cecile: great aunt to Wiley Wright and grandmother to Helene; took Helene from the Sundown House and reared her in New Orleans

Helene Sabat: daughter of a Creole prostitute; born behind the red shutters of Sundown House

Wiley Wright: nephew of Cecile; resided in Medallion, Ohio; married Helene Sabat, when she was 16; a seaman in port only three days out of every 16; served as cook aboard the ship

Nel: the daughter of Helene and Wiley after their ninth year of marriage

Henri Martin: New Orleans resident who writes to Helene to tell her of her grandmother’s illness

Porter: the colored man who points Helene and Nel to the coach

Conductor: the white man who calls Helene “gal” and who questions Helene’s and Nel’s presence in the white section of the coach

Black woman and her four children: passengers who boarded in Tuscaloosa; the woman shows Helene and Nel the field that is used for a restroom

Rochelle: Helene’s mother and Nel’s grandmother

Eva: Sula’s grandmother

Hannah: Sula’s mother; Eva’s oldest child

Summary

Helene Sabat was born in Sundown House in New Orleans; her mother was a prostitute. Her grandmother Cecile took the child to rear. Young Helene married Wiley Wright and returned with him to Medallion, Ohio. Wiley was a seaman who was home only three days out of every 16. His job aboard the ship was to cook. After nine years, Wiley and Helene had a baby girl, whom they named Nel.

Helene received a letter from Henri Martin. The letter said that Cecile was sick. Armed with her manner, her bearing, and a new dress, Helene decided to return to New Orleans. She and her daughter traveled by train in November of 1920.

On the train they made a mistake and entered the wrong car. The conductor talked demeaningly at the pair, and Helene did the unthinkable: she smiled! The smile brought the contempt of all the black men in the car. Nel saw her mother turn to custard. Nel resolved never to bring this look on herself.

The trip south took two days. Helene and Nel left behind the areas where the restrooms were marked “White” and “Colored” and entered an area where the restroom for them was just a field of grass.

Helene and Nel arrived too late to see Cecile; Cecile had died shortly before their arrival. Nel met Rochelle, Helene’s mother. Nel made a discovery on this trip—her first and last from Medallion. Nel found that she was her own person- independent of anyone else.

Nel formed a bond of friendship with Sula. Each preferred the home of the other. Nel’s mother manipulated others and kept her home oppressively neat. Sula’s home was quite different; her mother, Hannah, never scolded or manipulated. Guests were frequent in Sula’s home and dirty dishes remained in the sink. Eva, Sula’s one-legged grandmother, read dreams to the girls and gave them peanuts from her pockets.

Analysis

This chapter is rich with contrasts; the author uses antiphonal characteristics to make the characters and settings more vivid. Morrison describes the contrasting homes and families of Sula and Nel in detail. Medallion and New Orleans were unlike in many ways; Morrison notes some of these differences. Nel discovers marked contrasts as the train approaches the South.

Diction is an important part of constructing the characters for the reader. Morrison records Rochelle’s Creole carefully for the reader: “‘I don’t know what happen to de house. Long time paid for. You be think’ on it? Oui?’” The words of the black woman who had boarded the train in Tuscaloosa reflect the speech of the South: “Yonder” and “We be pullin’ in direc’lin.”

Morrison takes the reader inside the mind of Nel and allows the reader to view the happenings through Nel’s perspective. The reader finds that Nel sees her mother as “custard” after the encounter with the conductor and dislikes what she observes. Nel even takes some satisfaction in the discomfort of her mother in the presence of the conductor and the men in the train car.

Identity is an important theme in this chapter. Young Nel begins to establish an identity of who she is. After her return to Medallion, Nel says, “‘I’m me. I’m not their daughter. I’m not Nel. I’m me. Me.’” Nel’s attitude is similar to Morrison’s; Toni Morrison admits that she does not allow others to control her feelings toward herself.

Morrison continues to use stylistic devices. For example, a metaphor is evident when Nel calls Rochelle a “painted canary.” Descriptive passages help the reader to visualize the sights that Nel sees; one example is when Morrison notes “...the muddy eyes of the men who stood like wrecked Dorics....”

The imagery that Morrison uses when she describes Sula’s house allows the reader to experience the sights, sounds, and feelings of a visitor:

“...As for Nel, she preferred Sula’s woolly house, where a pot of something was always cooking on the stove; where the mother, Hannah, never scolded or gave directions; where all sorts of people dropped in; where newspapers were stacked in the hallway, and dirty dishes left for hours at a time in the sink, and where a one-legged grandmother named Eva handed you goobers from deep inside her pockets or read you a dream.”

Sula describes the friendship of two women. Such a story was unusual in its day. The theme of women’s friendship was a topic not generally treated in the 1970s.

Study Questions

- Where did Wiley Wright live?

- Whom did Wiley Wright marry?

- What was Wiley Wright’s daughter’s name?

- In what city was Helene born?

- Who was Helene’s mother?

- In what house was Helene born?

- How did Helene and Nel know that they were too late to see Cecile alive?

- What was Helene’s reaction when the conductor spoke disparagingly to her?

- Which of the discoveries that Nel made on her trip to New Orleans was most important?

- Who was Nel’s friend?

Answers

- Wiley Wright lived in Medallion, Ohio.

- WileyWright married Helene.

- Nel was Wiley Wright’s daughter.

- Helene was born in New Orleans.

- Helene’s mother was Rochelle.

- Helene was born in Sundown House.

- Helene and Nel knew that they were too late to see Cecile alive when they saw the black crepe wreath with the purple ribbon.

- When the conductor spoke disparagingly to Helene, Helene smiled, and that brought her the contempt of the black men in the train car.

- The most important discovery that Nel made on her trip to New Orleans was that she was herself, not her parents or anyone else.

- Nel’s friend was Sula.

Chapter Three: 1921

New Characters:

BoyBoy: Eva’s husband and Sula’s grandfather

Pearl: Eva’s daughter; real name is Eva; younger than Hannah; aunt of Sula; married at 14 and moved to Flint, Michigan

Plum: Eva’s son; real name is Ralph

Suggs family: gave food to Eva and her children; gave castor oil to Eva when Plum was constipated; poured water on Hannah when fire consumed her

Mr. and Mrs.Jackson: gave milk to Eva and her children

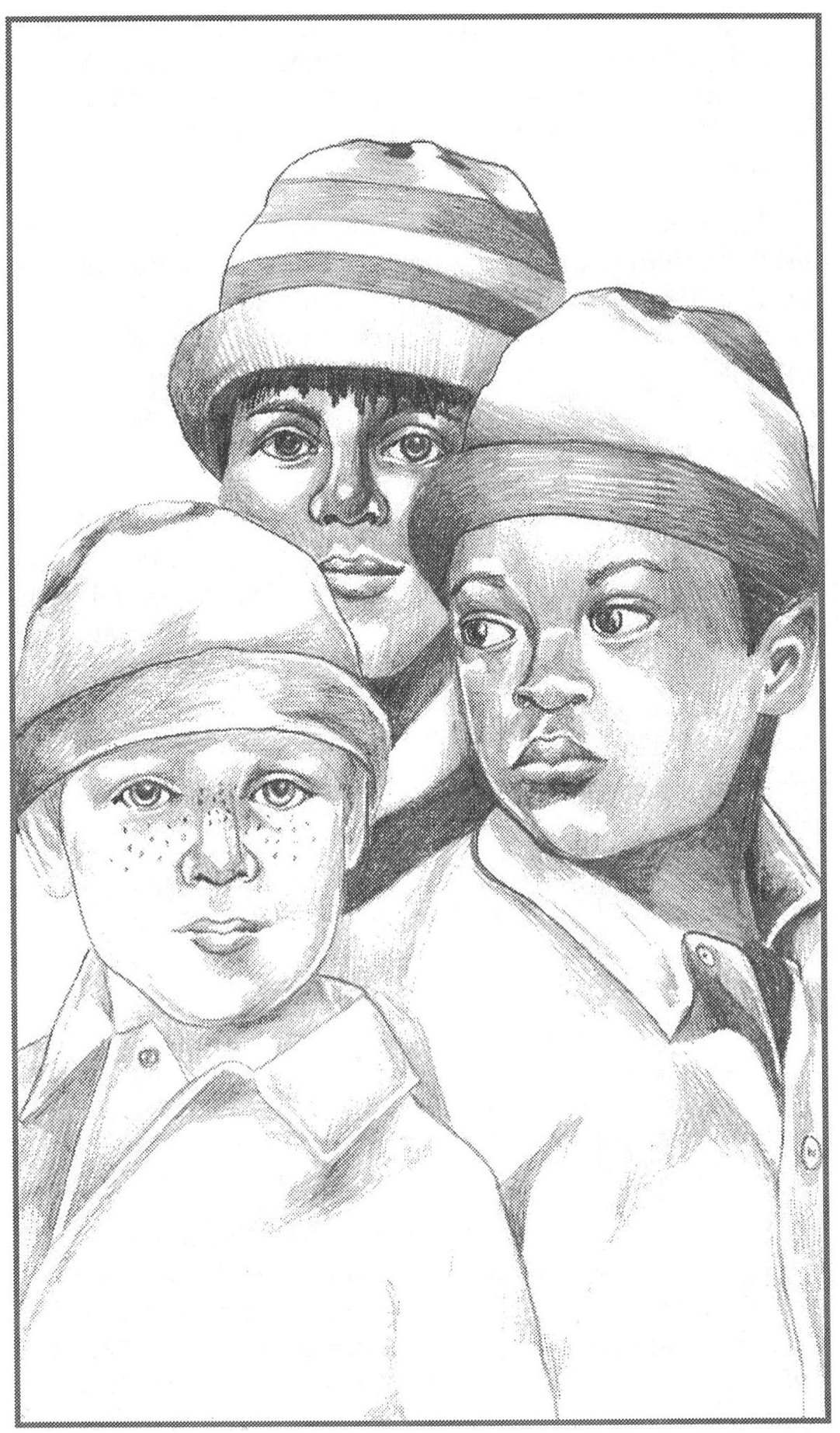

Eva’s adopted children: all three named dewey; one with red hair and freckles, one half-Mexican, one deeply black; no individuality of mind

Rekus: husband of Hannah; father of Sula; died when Sula was three

Tar Baby: along with the deweys, first to follow Shadrack; came in 1920; had some—or all—white blood; mountain boy; alcoholic

Mrs. Reed: teacher; gave all three deweys the last name of King and the same age

Buckland Reed: husband of the teacher, Mrs. Reed; takes numbers from the residents of the Bottom; makes a comment about Eva’s leg being worth $10,000

Summary

Sula Peace lived in a house built to the specifications of her grandmother, Eva Peace. Eva was the African-American owner who added to the house over a five-year period. Her whims and requirements changed during this time. Some rooms had three doors; others, only one. Some rooms opened onto porches; some had no entrances from the inside.

Eva’s husband was BoyBoy. They had three children: Hannah, Eva (also known as Pearl), and Ralph (also called Plum). BoyBoy did what he liked: womanize, abuse Eva, and drink. He left Eva after five years of marriage; she had only five eggs, $1.65, three children, and three beets.

Eva depended on neighbors like the Suggs family and the Jacksons for food and milk. One night after helping Plum end a bout of severe constipation, Eva left the children with the Suggs family “for a day.” Eighteen months later she came back with one leg, two crutches, a new pocketbook, and fanciful tales about the loss of her leg. Eva gave Mrs. Suggs $10.00 and began building a house near the cabin where she and BoyBoy had lived. She rented the cabin which now had an outhouse, although it did not have one for the first year she and BoyBoy had occupied it.

BoyBoy returned to visit when Plum was three. Uncertain of her emotions, Eva served BoyBoy lemonade. They talked politely for a while until he, with his smell of money and new clothes, returned to his city woman who waited for him under the pear tree. Eva now felt toward BoyBoy only one emotion: hate. She began to retreat to her room and left only once after the year 1910. On that occasion Eva started a fire, the smell of which remained in her hair for months.

In 1921, Eva took in three children she saw from the balcony. She named all three dewey. The three deweys were inseparable. She also took in a man she called Tar Baby. He was interested only in drink. He and the three deweys eventually became the first to join Shadrack in the celebration of National Suicide Day.

Like their mother, the Peace women loved men. Pearl married at 14 and moved to Flint, Michigan. Hannah married Rekus, who fathered Sula. Rekus died when Sula was three. Sula is aware of the fact that her mother begins to entertain men in their home; she sees her mother enter the pantry with men. From Hannah, Sula learns that sex is pleasant, frequent, and unremarkable.

Eva’s last child was Ralph, or Plum. Plum went to war in 1917. When he returned in 1919, he did not come directly home. He spoke little, slept a lot, stole from his family, and became very thin. Hannah found a bent spoon which was black from cooking (a sign of drug abuse).

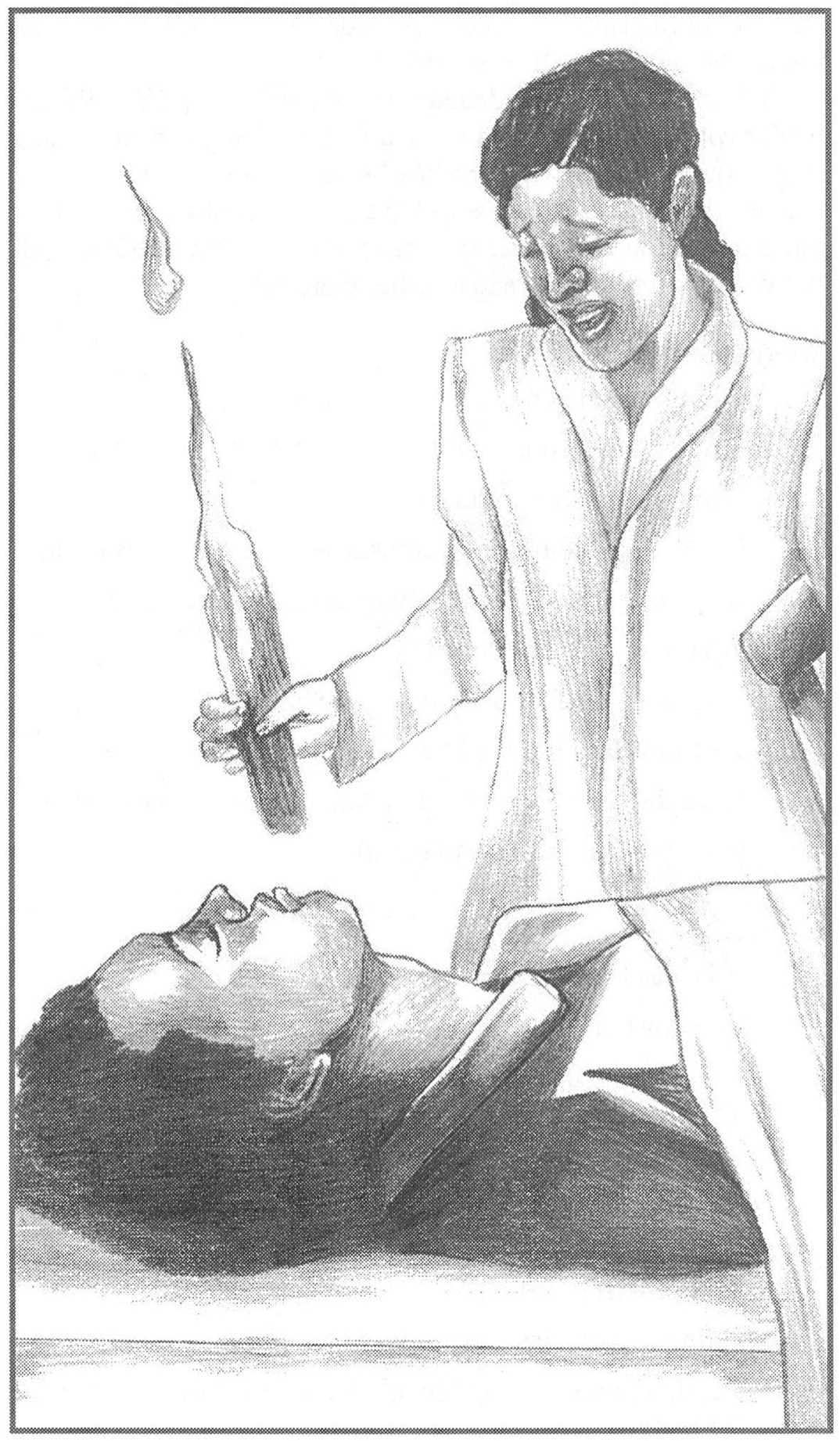

One night, Eva went to Plum’s room, gathered Plum in her arms, and rocked him. She got some items from the kitchen and returned to his room. She doused him with kerosene and set him on fire.

Analysis

Conflict is the distinguishing feature of this chapter. It is the desire for resolution of conflict in the plot that keeps the reader attentive to Sula. There are many types of conflict in “1921.”

A recurring conflict in “1921,” and in the entire book, is that between individualism and conformity. Eva tries to make the adopted children she called dewey alike; even the teacher, the narrator admits, cannot tell the children apart even though they are quite different in appearance. The children, however, are nonconformists and try to resist the molds imposed upon them. They join with another who is an individual: Shadrack.

Another conflict apparent in “1921” and in the book as a whole is the conflict between good and evil. The reader wants to know if evil or good brought about Plum’s death. The reader wants to know if one will triumph over the other in the book and in the lives of the people of the Bottom.

The character Hannah experiences a different type of conflict. Hannah has a conflict with society. Because of her “loose” lifestyle, Hannah makes many enemies in the community. Morrison explains that the “good” women object to her activities; the prostitutes object to the free trade Hannah gives; and the other women object to her liaisons without love or emotion.

Conflict between characters is an integral part of “1921.” The reader finds out about the conflicts between Eva and BoyBoy and between Eva and Plum. Conflict between person and self is also evident when Eva must make the decision to leave her family and to burn her son to death. Fire figures prominently in Sula, as it did in Morrison’s life.

Morrison weaves the theme of love throughout the chapter. The love objects and acts of love vary. Hannah has sex with the men in the Bottom for pleasure—not love. Plum exhibits love—for drugs. Tar Baby also loves wine. BoyBoy loves three things: drink, women, and abusing Eva.

The theme of good versus evil began with the contrasting of the Bottom and the valley and continues when the characters perform evil and disheartening acts: stealing from family, ignoring others and their needs, and setting fire to a family member—although Eva professed to have done this in love.

Throughout the novel Eva equates her love for others with responsibility. This constant expression of responsibility makes Eva a static character. Eva expresses love for her dynamic (changing) son Plum through her “responsible actions.” She must make sure that Plum succeeds as a man because she loves him. This love and the resulting responsibility make it necessary for Eva to burn her son to death.

A strong feature of the chapter and of Morrison’s writing is her effective characterization. Morrison reveals many dimensions of the round, important characters to make them real to the reader. An analysis of Morrison’s methods of characterization shows that her techniques vary from one character in Sula to another. For instance, Morrison uses many different techniques with the pivotal character of Eva Peace. The reader is able to see Eva through many eyes and through many devices. For example, Morrison calls Eva Peace the “creator and sovereign”; this is an example of the narrator/writer giving the reader an opinion. The writer shows Eva in action to help reveal her completely; for instance, the reader finds Eva sitting “in a wagon on the third floor directing the lives of her children, friends, strays, and a constant stream of boarders.” Eva is proactive as she takes in children and retreats to her bedroom.

The narrator inserts words which give the reader information about Eva Peace. This static character expresses her love for others—even visiting children—through her responsible actions; for instance, she is the perfect hostess when “...she began some fearful story about it [her missing leg]—generally to entertain children.”

The reader finds that Eva’s diction makes her a real person; for instance, she responds, upon hearing of Plum’s dying moments, “‘Is? My baby? Burning?”’ Another means of characterization are the actions of others toward Eva; for example, the readers find that “Unless Eva herself introduced the subject, no one ever spoke of her disability; they pretended to ignore it....” Eva’s physical description and the impression she makes on others help to round out the picture of her:

“...the remaining one [leg] was magnificent...Her dresses were mid-calf so that her one glamorous leg was always in view... [Her] wagon was so low that children who spoke to her standing up were eye level with her, and adults, standing or sitting, had to look down at her... But they didn’t know it. They had the impression that they were looking up at her, up into the open distances of her eyes, up into the soft black of her nostrils and up at the crest of her chin.”

An important part of the chapter is the setting, particularly the house where Sula lived. The description of the house itself is graphic.

“Sula Peace lived in a house of many rooms that had been built over a period of five years to the specifications of its owner, who kept on adding things: more stairways—there were three sets to the second floor—more rooms, doors and stoops. There were rooms that had three doors, others that opened out on the porch only and were inaccessible from any other part of the house; others that you could get to only by going through somebody’s bedroom....”

The creator and sovereign in this house lives at the highest level: the third floor—which signifies Heaven and the supreme location. The others in the family are in the nether regions.

The time frame for “1921” does not adhere to a strictly chronological arrangement. There are flashbacks; for instance, the narrator takes the reader back in time to the construction of the Peace home, ahead to the time of the troubled marriage of BoyBoy and Eva, and ahead to the year 1921 when Eva burns Plum.

Morrison uses many stylistic devices in “1921” to make the action, the characters, and the setting real to the reader. She uses the onomatopoeic word “whoosh” to describe the sound of the flames as they engulf Plum. The diction that Morrison very carefully records is another important stylistic device. For example, Eva says, “‘Tell them deweys to cut out that noise.’” Connotation helps the reader draw a picture of Tar Baby; Morrison describes his “milky skin and cornsilk hair.” Through the use of a simile, the reader can feel the emotions of Eva when BoyBoy comes to visit:

“...It hit her like a sledge hammer, and it was then that she knew what to feel. A liquid trail of hate flooded her chest.”

Imagery is an important part of the chapter. Morrison writes:

“...Eva squatted there wondering why she had come all the way out there to free his stools, and what was she doing down on her haunches with her beloved baby boy warmed by her body in the almost total darkness, her shins and teeth freezing, her nostrils assailed.”

There is foreshadowing, another stylistic device, in the chapter. The reader suspects that when Sula learns that sex is pleasant, frequent, and unremarkable, she will follow in the footsteps of her mother.

It becomes evident to the reader, particularly in “1921,” that Sula is a tragedy. It seems doubtful that all the conflicts can be resolved to the satisfaction of the reader. Further tragic developments seem likely as the plot unfolds.

The chapter is not a closed one. The author again leaves the reader with a desire to read more because there are many unanswered questions: How did Eva lose her leg? Where did Eva go when she left the children? Where did Eva get the money to build the rambling house? What was the result of the fire? Why did Eva kill Plum? The reader must read another chapter!

Study Questions

- What was Sula’s relationship to Eva?

- Who was Eva’s husband?

- Name Eva’s three children.

- How was Eva different when she returned to the Bottom?

- How was Plum different when he returned to the Bottom?

- What happened to Plum?

- Who were the first people to join Shadrack?

- Why did Hannah make love during the day?

- What did Sula learn about making love from her mother?

- What was Tar Baby’s bad habit?

Answers

- Sula was Eva’s granddaughter.

- Eva’s husband was BoyBoy.

- Eva’s three children are Hannah, Plum (or Ralph), and Eva (or Pearl).

- Eva was different when she returned to the Bottom because she was missing a leg.

- Plum was different when he returned to the Bottom because he was a drug addict.

- Plum’s mother, Eva, set him on fire.

- The first people to join Shadrack were the three deweys and Tar Baby.

- Hannah made love during the day because sleeping with someone was a commitment and an act of trust.

- Sula learned from her mother that making love was pleasant, unremarkable, and a frequent occurrence.

- Tar Baby’s bad habit was drinking wine.

Suggested Essay Topics

- Describe as completely as possible the house built over a five-year period by an owner whose specifications continued to change. Now, add your description of some other unusual features the house might have had.

- Change is a frequent feature of this chapter. Which characters seem to be dynamic, or changing, characters? Are there characters in this chapter who are static, or nonchanging? Explain your answer.

Chapter Four: 1922

New Characters:

Ajax: 21-year-old man with sinister beauty; a frequenter of the pool halls; calls Sula “pig meat” when he sees her; Sula’s lover

Chicken Little: a little boy whom Sula swings around; drowns when he slips from Sula’s hands and goes into the lake

Patsy and Valentine: Hannah’s two friends who are visiting with her the day Chicken Little drowned

Four white, Irish boys: newly arrived residents of the Bottom; taunted the girls

Bargeman: the one who found Chicken Little’s body

Summary

The men in the community of the Bottom had a frequent haunt to watch girls and women pass. They squatted on Carpenter’s Road, the four blocks of businesses in the neighborhood. The old men were now kind and remembered the days past; they often tipped their hats. The young men opened and closed their thighs. All stared at the girls and women as they passed.

Ajax was one of the young men who frequented the area and hurled epithets. Often the words he used were harmless, but his way of saying them gave him a reputation of having a foul mouth. When Nel and Sula deliberately pass these boys and men on the excuse of wanting to get ice cream—which it was really too cool to enjoy—Ajax called out the words, “pig meat.” The two 12-year-olds were delighted.

Four Irish boys often followed the girls from school and even tried to pass them from hand to hand, tear their clothes, and do anything else they were able to do to harass them. Sula, with her birthmark that looked like a long-stemmed rose, and Nel, with her developing body, usually avoided the path the boys might take. One day, however, Sula persuaded Nel to take the shortest way home with her. When the boys began to follow them, Sula cut off the tip of her finger in order to show the boys her lack of fear and what she could do to them.

Nel’s mother wanted her daughter to be attractive. Each Saturday she had Nel use the hot comb. Each night she sent Nel to bed with a clothespin on her nose. Nel began to slip the pin under the cover each night after she met Sula.

One hot summer day the girls decided to follow the boys to the lake. Sula slipped back into her house to use the bathroom and heard her mother say that she did not like her daughter even though she loved her. Sula was very upset, but she did not tell Nel what she heard.

When the girls arrived at the lake, they dug two holes and put in glass, rocks, leaves, and other debris. They climbed a tree with Chicken Little. Sula took him by his arms and swung him around; Chicken Little slipped from her arms, flew into the lake, and drowned.

Sula was afraid that someone had seen. She ran to see if Shadrack could have observed what happened. She found Shadrack’s cabin. When he surprised her, she turned to ask him a question. He, however, answered a question she had never asked. His answer was, “Always.”

Nel assured Sula that she had not meant to drown Chicken. Nel said that it was not Sula’s fault. Nel was also very concerned because Sula had lost her belt.

Because of the unimportance the white men placed on the child’s dead body and his family’s feelings, it was three days before the family received Chicken’s body. At the funeral, the girls appeared deeply moved. The women acknowledged that the only way to escape the hand of God was to get in it. The girls held each other’s hands tightly. Gradually their hand clasp loosened, and they appeared like any other young girls.

Analysis

Morrison makes use of many stylistic devices in this chapter. When Sula enters Shadrack’s cabin, Morrison uses personification: “...heard the hinges weep.” She uses imagery, for instance, when she describes Nel and Sula as “wishbone thin.” Dialect is evident as Chicken says “I’m a tell my brower.” She uses alliteration when she writes “the neatness, the order startled her, but more surprising was the restfulness.” A metaphor is evident when the writer describes Nel and Sula walking through a “valley of eyes.” Morrison uses contrasts to describe the street, or valley of eyes, even further; she describes the road as being “...chilled by the wind and heated by the embarrassment of appraising stares.” A simile is used to describe the two girls as being “like tightrope walkers.” Imagery is a descriptive technique used to describe the weather: “A summer limp with the weight of blossomed things.” Morrison makes an allusion to the Bible and the Biblical character Ham.

In this chapter, Morrison frequently uses the stylistic device of connotation; that is, she does not say exactly what she means. Instead she makes a reference to something else to create the feeling she wants the reader to have. For example, Morrison refers to “the smell of hot tar”; to comprehend the expression, one would have to have experienced the smell.

The themes of loneliness and sexism are important parts of “1922.” Morrison discusses the loneliness of the two girls before their friendship began. She describes the sexual harassment of the men as they stare at the women and girls walking past. She refers to sexism again when she states that Sula and Nel “...were neither white nor male, and that all freedom and triumph was forbidden to them...” She experienced sexual and racial harassment in her own life.

Racism is an important theme in “1922” and figures prominently into the incidents surrounding the death of Chicken Little. A white bargeman finds the body that afternoon, but it is too much trouble for him, the ferryman, or the sheriff to inform the family. It is three days before the family receives the body.

Morrison allows the reader to enter the mind of the white bargeman to show his ugly, hate-filled, racist thoughts. The bargeman immediately assumes that Chicken Little’s own parents have drowned the child. The reader finds that the bargeman regards the African-Americans as nothing “...but animals, fit for nothing but substitutes for mules, only mules didn’t kill each other the way niggers did.”

The sheriff and the bargeman speak openly and voice their racist attitudes. The sheriff asks why the bargeman did not just throw the body back in the water. The bargeman admits he should have never taken it out in the first place. At last, the ferryman agrees to take the body back in the morning—not at once.

The reader is also aware, through Morrison’s writing, of the racism in the community of Medallion—there is discrimination as well as reverse discrimination. For instance, the reader finds that when some Irish move into the area, they encounter:

“...a strange accent, a pervasive fear of their religion and firm resistance to their attempts to find work....In part their place in this world was secured only when they echoed the old residents’ attitude toward blacks.”

Morrison gives a hint of the events to come with her foreshadowing. She writes that “The birthmark was to grow darker as the years passed, but now it was the same shade as her gold-flecked eyes, which, to the end, were as steady and clean as rain.” (This birthmark and water or rain are to figure prominently throughout the book.) On the same page Morrison mentions that there was a time when Sula would retain a mood for weeks in defense of her friend Nel. Another example of foreshadowing—this time a hint of Chicken Little’s death—occurs when the girls dig and fill a grave.

The words “saw” and “watch” are important words in the chapter. The men watched the women and girls walk past them; the word “watched” implies they deliberately stopped. Sula is afraid that someone saw Chicken Little drown; the word “saw” indicates that one caught a glimpse of something—perhaps unintentionally. The words will surface again later in the book.

There is a parallel between Shadrack and Sula in the chapter. Both appear not to be afraid of death or pain, but they both seem to fear the uncertainty of when it may come. Like Shadrack, Sula tries to gain control over the conditions and seeks to force the boys into showing their hand when she has control of the situation.

It is significant that the boys drop all pretense of innocence when Sula shows them the knife. This theme of innocence has already surfaced in the introduction when the slave owner dupes the (innocent) slave into taking the hill land.

Morrison reveals more of the character of Shadrack through “1922.” The surroundings of Shadrack tell the reader about the character:

“...The neatness, the order startled her, but more surprising was the restfulness. Everything was so tiny, so common, so unthreatening....This cottage? This sweet old cottage? With its made-up bed? With its rag rug and wooden table? Sula stood in the middle of the little room...”

Physical features—the hands of Shadrack—and their movements when Sula goes to his cottage divulge a side of Shadrack the reader has not seen before:

“... she saw his hand resting upon the door frame. His fingers, barely touching the wood, were arranged in a graceful arc. Relieved and encouraged (no one with hands like that, no one with fingers curved around wood so tenderly could kill her)...”

Shadrack’s words and his facial expressions when he speaks give Sula and the reader information about this person:

“He was smiling, a great smile, heavy with lust and time to come. He nodded his head as though answering a question, and said in a pleasant conversational tone, a tone of cooled butter, ‘Always.”’

The narrator adds to Shadrack’s character revelation in “1922.”

“...The terrible Shad who walked about with his penis out, who peed in front of ladies and girl-children, the only black who could curse white people and get away with it, who drank in the road from the mouth of the bottle, who shouted and shook in the streets...”

Again, the author makes the reader continue to read. Also, Morrison once more leaves the reader with many unsettled questions. What happened to the belt? Will the sheriff find out about Sula’s crime? Has Shadrack really been watching them?

Study Questions

- What did Nel’s mother want Nel to do to make her nose attractive?

- How did Sula convince the boys that she was not afraid of them and could take care of herself?

- What disturbing thing did Sula hear her mother say?

- How did Chicken Little die?

- How long was it before the family of Chicken Little received his body?

- Who found the body of Chicken Little?

- What answer did Shadrack make to the unasked question?

- What did Sula lose when Chicken Little died?

- What does Morrison say happens to a handclasp?

- What did Nel say about Sula’s part in the accident?

Answers

- Nel’s mother wants Nel to sleep with a clothespin on her nose to make her nose more attractive.

- Sula convinced the boys she was not afraid of them by showing them a knife and cutting off the tip of her own finger.

- Sula heard her mother say she loved but did not like her daughter.

- Chicken Little drowned when his body flew from Sula’s grasp while she was swinging him near the water.

- It was three days before the family of Chicken Little received his body.

- The bargeman found the body of Chicken Little.

- Shadrack’s answer to the unasked question was, “Always.”

- Sula lost her belt when Chicken Little died.

- Morrison said a handclasp would stay above ground forever.

- Nel told Sula that it was not Sula’s fault.

Suggested Essay Topics

- Morrison writes that Nel and Sula stood away from the grave after the service.

“...They held hands and knew that only the coffin would lie in the earth; the bubbly laughter and the press of fingers in the palm would stay aboveground forever.”

What do you think she meant by this passage? Explain your answer fully. - Morrison mentions the most dreadful pain that there is. What does she say that this pain is? Explain what she means.

Chapter Five: 1923

New Characters:

Iceman: delivers ice to the homes

Willy Fields: orderly who saved Eva from bleeding to death and received her curse for doing so the rest of her life

Summary

In this chapter, the second strange thing happens; Hannah brought a peck of Kentucky Wonders into Eva’s room and asked if Eva ever loved her children.

Eva reprimanded her daughter for wondering and reminded Hannah that there was no playing in 1895. Eva began to reflect on an earlier time. She remembered her husband leaving her, Plum’s constipation, and the three beets which were all she had when her husband left. Eva remarked that Hannah would have been dead if Eva had not loved her.

Hannah asked a second question: why had Eva burned Plum? Eva explained to Hannah that she burned Plum because he tried to return to her womb through his drugs and because she wanted him to die like a man.

The wind was the first strange thing that happened that day. The people welcomed the wind, however, because they thought that it meant rain.

Hannah lay down for a while after washing the beans and dreamed of a wedding in a red dress. She mentioned this dream to her mother at breakfast; she had brought her mother scrambled eggs without the whites to bring them good luck on their number choice. Neither she nor her mother bothered to look the dream number up because they both knew the dream number was 522. Eva said she would place bets on that number when Mr. Buckland Reed came. This was the third strange thing.

Hannah went into the yard and kneeled to light the yard fire for canning. Eva watched her from her window. When Eva returned to the window after searching for her lost comb, she saw that Hannah was on fire; this strange thing was the fourth strange happening—or fifth, depending on whether the reader counts Sula’s craziness in watching Hannah burn.

Eva threw herself through the window and tried to place her own body over the flaming body of Hannah. Hannah moved about in the flame, and Eva could not reach her in time. Mr. and Mrs. Suggs poured the tub of hot water, with the tomatoes still in it, on Hannah. It was too late. Hannah died—probably on the way to the hospital with her bleeding mother beside her in the ambulance.

Eva would have bled to death at the hospital had it not been for the orderly Willy Fields. Everyone seemed to have forgotten Eva, and Willy reminded them that there was another patient there. Eva, however, was not grateful for the rescue and cursed Willy every day for 37 years until she was 90; Eva would have cursed him longer, but she became forgetful.

Eva decided the red in the dream Hannah had before her death symbolized fire and that the wedding meant death. She also recalled and told others that she had seen Sula looking as Hannah burned.

Analysis

Morrison entices the reader to continue reading from the first sentence of the chapter. Morrison mentions “the second strange thing that happened.” The sentence makes the reader want to read on and to find out about the first strange thing which happened. This sequence keeps one turning the pages. To cause even further curiosity in the reader, in the same sentence is a reference to Kentucky Wonders ; most readers will not know what these are. There is, therefore, at least one problem with no immediate solution to keep the reader engaged in reading Sula for a while longer.

The chapter is not in chronological order. There are flashbacks, a stylistic device that Morrison employs frequently. For instance, Eva reflects on an earlier time when she sat in the cold outhouse with the baby Plum. Morrison also uses foreshadowing—a glimpse into or a hint about the future. She tells the reader that Eva lives a long time. The chapter title “1923,” then, is not a chronological chapter as its title might lead one to suspect.

Morrison makes use of imagery to give the reader a clear picture of the action of finding Eva after Hannah’s burning. For instance, she writes:

“...They found her on her stomach by the forsythia bushes calling Hannah’s name and dragging her body through the sweet peas and clover that grew under the forsythia by the side of the house...The blood from her face cuts filled her eyes so she could not see, could only smell the familiar odor of cooked flesh.”

The writer goes into the minds of several characters, primarily Eva and Hannah. Eva reveals that Sula is interested in watching her mother burn. The reader, however, still wonders why Sula watched Hannah burn without helping; this means that the chapter is an open-ended one that keeps the reader interested and ensures that the reading continues.

Morrison makes use of many stylistic devices. For instance, she uses similes. An example of one of these descriptive phrases using like is “...gesturing and bobbing like a sprung jack-in-the-box.” Morrison’s careful renditions of the characters’ diction give the reader a flavor of the time. For instance, Eva says, “‘Give me that again. Flat out to fit my head.”’

Morrison’s own grandmother made use of dream books; Morrison’s knowledge of this technique and of superstitions affects the content of the chapter. In “1922,” Hannah has a dream about a red dress and a wedding; both Hannah and Eva know the dream book well enough to know the number for that dream is 522. They plan to use that number for placing their bets when Mr. Buckland Reed comes; this reminds the reader of Morrison’s grandmother. To help ensure their good luck, Hannah brings Eva scrambled eggs with the whites left out. Sula is 13 (unlucky); this is a time when she is an adolescent and no longer a child and when she loses her mother to fire. These references indicate the writer’s own knowledge of superstitions.

Morrison uses irony after this incident. The good luck they had hoped for turns into bad luck. Hannah burns to death and Eva is almost killed trying to save her daughter. Symbolism plays a part in the incident. From her hospital ward Eva remembers that weddings mean death and the red wedding gown symbolizes the fire; Morrison again weaves her knowledge of superstition and family heritage into the writing. The cool ice in the beginning of the chapter turns to fire.

An important theme in the chapter is love. Hannah begins by asking Eva if she loved Hannah, Pearl, and Plum. Eva equates responsibility with love in her answer. When Hannah asks why Eva burned Plum, Eva explains that Plum tried to return to his mother’s womb and that she made sure he behaved as a man; she was, in effect, exercising responsibility through setting fire to Plum because of her love for him. Sula, on the other hand, does not indicate her love for her mother by exercising responsibility for her mother’s well-being. Neither did she take the responsibility earlier for Chicken Little’s death.

Hannah’s dress catches fire. (The reader remembers the fire that also was a part of Morrison’s childhood.) Eva almost dies trying to save her daughter—again equating her love with her responsibility.

The word watch surfaces in the chapter “1923” as it did in the chapter “1922.” This time the question is whether Sula watched Hannah burn or saw her mother burn? Did she stop what she was doing and stare as the men did when the women passed them on Carpenter’s Road? Was Sula interested or paralyzed? Why did she not exercise responsibility? Was her inaction an indication of a lack of love?

The theme of good and evil, Heaven and Hell, is again present in Sula. Plum has been evil with his drug use, and Hannah says she does not like her own daughter; both receive the punishment of fire or Hell. Eva remembers helping Plum with his constipation and receives coolness as a heavenly reward in the summer heat. These “just dues” are reminiscent of Dante’s Inferno.

To ensure that the reader continues to turn the pages, Morrison leaves the reader wondering why Sula really did nothing as her mother burned.

Study Questions

- What was the first strange thing that happened?

- What was the second strange thing that happened?

- What are Kentucky Wonders?

- In what year did Eva’s husband leave her?

- What was the number that Eva and Hannah both knew from the dream book?

- How did Mr. and Mrs. Suggs put out the fire on Hannah?

- Who saved Eva’s life in the hospital?

- Whom did Eva see not helping Hannah during the fire?

- How long did Eva curse Willy?

- What dream did Hannah have before the fire?

Answers

- The first strange thing that happened was the wind.

- The second strange thing that happened was when Hannah took the Kentucky Wonders and a bowl into her mother’s room.

- Kentucky Wonders are a type of green bean or string bean.

- Eva’s husband left her in 1895.

- The number that Eva and Hannah both knew from the dream book was 522.

- Mr. and Mrs. Suggs put out the fire on Hannah by throwing a tub of hot water—with tomatoes still in it—on the burning woman.

- Willy Field was the orderly who saved Eva’s life in the hospital.

- Eva saw Sula not helping Hannah during the fire.

- Eva cursed Willy for 37 years for saving her.

- Hannah dreamed of a wedding and a red wedding dress.

Suggested Essay Topics

- Love is an important theme in Sula. Discuss the words about love or lack of love evident at this point between Eva and her daughter Hannah, between Sula and her mother Hannah, and between Eva and Plum.

- Discuss the reactions of Sula and Eva when they see Hannah on fire. Is there a difference? Do one’s actions always reflect one’s feelings? Explain.

Chapter Six: 1927

New Character:

Jude Greene: tenor in Mt. Zion’s Men Quartet; 20-year-old bridegroom of Nel Wright; waiter at Hotel Medallion; leaves with Sula

Summary

Helene Wright was tired but happy in preparing for her only daughter’s wedding. Not many people in Medallion had church weddings with receptions. Such weddings were expensive; couples married at the courthouse or “took up” with each other. The Wrights mailed no invitations; everyone just came. Those who could afford a gift brought it; those who could not afford a gift could come without one.

Jude Greene, the bridegroom, had wanted to work on the New Road. His job as waiter at the Hotel Medallion was not what he wanted to do with his life. His rage, his determination to take a man’s role, and his need of someone to care for him resulted in his asking Nel to marry him. He particularly liked Nel because she was not trying to get him to notice her. When he presented his problems, Nel cared. She accepted his proposal of marriage.

At the wedding, Morrison tells the reader, everyone realized that the deweys had been 48 inches tall for years and would always remain child-like in thought and action.

At the end of the reception the couple danced together and anticipated their first night as husband and wife. Nel sees Sula over Jude’s shoulder.

Analysis

Morrison includes many stylistic devices in “1927.” An example of connotation is the following:

“Even Helene Wright had mellowed with the cane, waving away apologies for drinks spilled on her rug and paying no attention whatever to the chocolate cake lying on the arm of her red-velvet sofa.”

Alliteration (“... come crashing down on his foot, and when people asked him how come he limped, he could say... ”) and a metaphor (“Whatever his fortune, whatever the cut of his garment, there would always be the hem... ”) are some of the ways that Morrison helps to describe the setting, the feelings, and theme of love in “1927.”

In describing the wedding and the reception Morrison uses contrasts: old dancing with young; church women tapping their feet; boys dancing with their sisters. Her writing is effective and presents an imagery to make the chapter real to the reader.

The road-building job symbolizes many important things to Jude. It is a way to remain a part of the world even after death. It is a good-paying job and will allow Jude to use his body to advantage. It is a way to find camaraderie. Even an injury from the hard road could be a badge of pride. Symbolism is important to the chapter and to Sula.

Racism is an important theme in “1927.” Jude is unable to secure the job because of his color. Jude’s color symbolizes something objectionable to the employers. The dark color of other Bottom residents also prevents them from getting jobs from the white employers. Instead of the well-built, black men, the employers hire Greeks, Italians, and skinny, white boys to work on the New Road.

Another theme in the chapter is love. Jude does not marry for love. He marries to have someone to care for him. He marries because he cannot have the job he wants and yet he wants to behave as a man. In the previous chapter Eva equates love with responsibility ; in this chapter, however, Jude does not marry with love or responsibility as a motive. He uses marriage to achieve an end: his own care. Racism against Jude, in effect, damages the life of others whom he touches.

Nel’s wedding is symbolic to her mother. The narrator states that Helene sees the wedding as “...the culmination of all she had been, thought or done in this world...” Morrison uses foreshadowing to indicate that Helene believes that with this wedding, her life’s work is over; she writes that “Once this day was over she [Helene] would have a lifetime to rattle around in that house and repair the damage.”

Identity is a prevailing theme in the book and in this chapter. Three boys who are different ages, from different ethnic groups, and from different backgrounds are very unlikely to reach the exact same size at the exact same time and to remain that exact same size forever—in body and in mind. The reader wonders if this has really happened or if others have defined the identity of the deweys. It appears that the deweys have allowed themselves to become what others want them to be; Morrison has always been bold about not allowing others to define her own life. The deweys have made no move to become separate from their counterparts; others have not bothered to try to recognize them. Mrs. Reed could not distinguish one dewey from the other even though they looked nothing alike and nothing like anyone before them. The neighborhood refuses to bother to tell them apart. The residents of the Bottom are, in effect, practicing reverse discrimination by saying, “They all look alike.” Unlike Nel, after her visit to New Orleans, the deweys never are able to say, “I’m me.”

Morrison ends the chapter with foreshadowing and leaves some unanswered questions for the reader.

“...It would be ten years before they saw each other again, and their meeting would be thick with birds.”

Study Questions

- What was the social event that Helene Wright was preparing for at the beginning of “1927”?

- Why did the Wright family not send invitations?

- In which quartet did Jude Greene sing?

- Where did Jude work?

- What job did Jude want?

- Why did Jude not achieve the job he desired?

- Why were the old dancing with the young, the church women tapping their feet, and the boys dancing with their sisters?

- How old was Jude at the wedding?

- Who left the Bottom at the end of the wedding?

- When would Sula return to the Bottom?

Answers

- The social event that Helene Wright was preparing for at the beginning of “1927” was the wedding of her only daughter, Nel.

- The Wright family did not send invitations because everybody in the Bottom came.

- Jude Greene sang tenor in the Mt. Zion Quartet.

- Jude worked as a waiter at the Medallion Hotel.

- Jude wanted a job as a road builder.

- Jude did not achieve the job he desired because of his color.

- The old were dancing with the young, the church women were tapping their feet, and the boys were dancing with their sisters because of the spiked punch.

- Jude was 20 years old at the wedding.

- Sula left the Bottom at the end of the wedding.

- Sula did not return to the Bottom for ten years.

Suggested Essay Topics

- What were the reasons that Jude asked Nel to marry him? Did any of the reasons have to do with love? Explain.

- Ajax at the Time and a Half Pool Hall said that with women, “‘All they want, man, is they own misery. Ax em to die for you and they yours for life.”’ Explain what he meant by this statement. Do you think it is a statement true of all women? Why?