Portrait of Lady Ise, from Nishiki hyakunin isshu azuma ori, an illustrated text of Hyakunin isshu by the eighteenth-century artist Katsukawa Shunshō.

Courtesy L. Tom Perry Special Collection, HBLL, Brigham Young University.

LADY ISE 伊勢, Iseshū 56: “Written as a poem by Emperor Xuanzong, when the Teijiin emperor had people write poems for a standing screen on various elements of The Song of Everlasting Sorrow”

|

Not yet swept clean, |

kurenai ni |

|

the ground of my garden court |

harawanu niwa wa |

|

has gone to crimson— |

narinikeri |

|

covered over with the leaves |

kanashiki koto no |

|

of my lamenting words. |

ha nomi tsumorite |

CONTEXT: The daughter of a provincial governor of Fujiwara lineage, Lady Ise (fl. 904–938) served in the court of a consort of Emperor Uda’s (867–931). More than twenty of her poems appeared in Kokinshū, the first imperially commissioned anthology of Japanese poetry, and she would be well represented in many other such collections in the centuries to come. This poem is from a group of five poems on the same Chinese theme in her personal anthology. Standing screens (byōbu) were standard furnishings in noble dwellings, used for decoration, to subdivide spaces, for privacy, and as windbreaks. At first, single-panel screens were the rule, but in time multiple-panel folding screens also developed. Unfortunately, no screens from the Heian period survive, but based on later examples we can surmise that Lady Ise’s poems for Emperor Uda accompanied illustrations in the yamatoe style of the story of Emperor Xuanzong (685–762) of the Tang dynasty, whose infatuation with a low-ranking lady named Yang Guifei led to political unrest and her death. Lady Ise’s poem would have been written on a square of paper that was then pasted on the screen as a cartouche.

COMMENT: The story of Emperor Xuanzong and Yang Guifei as told in “The Song of Everlasting Sorrow” (“Chang hen ge,” p. 93) by Bai Juyi (772–846) also figures in the background of the first chapter of The Tale of Genji, in which Emperor Kiritsubo is similarly infatuated with a woman, although with consequences less dire. We cannot be sure of the content of the painting, but Ise’s poem alludes to lines by Bai Juyi describing the state of the palace when the emperor returns home after putting down the rebellion.

With such sights before him, how could he not shed tears?

Peach trees blooming in the winds of spring,

Parasol trees shedding leaves in autumn rain.

Autumn grasses grow in West Palace and in South Court;

Fallen leaves cover the stairway, crimson not swept away.

Ise’s poem obviously reworks the material of Bai Juyi’s original. He employs a third-person narrator, but the headnote to Lady Ise’s poem tells us that she put her words in the mouth of the emperor himself. Thus her speaker addresses us from inside the story and “inside” the painting, adapting the perspective rather than simply mimicking the original. Since tears of sadness are often figured as bloodred in hue, the suggestion is that the garden court is covered not only with fallen leaves but also with the emperor’s tears.

ŌSHIKŌCHI NO MITSUNE 凡河内躬恒, Kokinshū 1005: “A long poem on winter”

|

The Tenth Month begins, |

chihayaburu |

|

when the mighty gods are gone. |

kannazuki to ya |

|

And that must be why— |

kesa yori wa |

|

why this morning first showers fall |

kumori mo aezu |

|

with the autumn leaves, |

hatsushigure |

|

from skies that though not clear |

momiji to tomo ni |

|

are not thick with clouds. |

furusato no |

|

From now on, as the days go by, |

yoshino no yama no |

|

winds will blow colder |

yamaarashi mo |

|

from the mountains of Yoshino, |

samuku higoto ni |

|

where once a palace stood. |

nariyukeba |

|

Hailstones will scatter all ’round, |

tama no o tokete |

|

so many jewels |

kokichirashi |

|

sprung from a broken necklace, |

arare midarete |

|

while frost freezes |

shimo kōri |

|

to make harder and harder |

iya katamareru |

|

the garden grounds— |

niwa no omo ni |

|

those grounds where winter grasses |

muramura miyuru |

|

growing in clumps |

fuyukusa no |

|

that show through here and there |

ue ni furishiku |

|

will lie beneath white snow, |

shirayuki no |

|

falling deeper and deeper still. |

tsumori tsumorite |

|

And thus a New Year |

aratama no |

|

I will add on to my store— |

toshi o amata mo |

|

one of many I have lived through. |

sugushitsuru ka na |

CONTEXT: Ōshikōchi no Mitsune (d. ca. 925) was a court official. By his time, those wanting to write longer poems had cast the chōka aside in favor of Chinese poetry. This poem is one of only six chōka included in Kokinshū, for which Mitsune served as a compiler.

COMMENT: Mitsune’s poem on the dai (topic) winter is in fact about advancing age. The narrator, writing in the first month of winter (the Tenth, when the gods leave their own shrines to assemble at Izumo Shrine), imagines images to come: first rain showers and falling autumn leaves, then storm winds, hail, frost, and snow. Although beginning and ending his poem with makurakotoba (chihayaburu kami, the “mighty” gods, and aratama no toshi, “new” or “rough-hewn” year), his diction is unadorned, a conventional rehearsal of seasonal progress that reads like a metaphorical preface (jo) for his last three lines of lament. He refrains from affecting a public voice, and gone are the various rhetorical amplifications of poets like Hitomaro. Storied Yoshino, for instance, does appear, but only as a source of storm winds and with no overt hint of its grand history.

KI NO TSURAYUKI 紀貫之 and ŌSHIKŌCHI NO MITSUNE, Teijiin uta-awase 13, 14 (Spring: “The Second Month”)

Left [winner]

|

Not truly cold |

sakura chiru |

|

is the wind that now scatters |

ko no shita kaze wa |

|

the cherry blossoms; |

samukarade |

|

and never has the sky known |

sora ni shirarenu |

|

snowflakes to fall like these. |

yuki zo furikeru |

|

Tsurayuki |

Right

|

Quite overcome |

waga kokoro |

|

by spring on the mountain slopes, |

haru no yamabe ni |

|

my heart tarries on: |

akugarete |

|

staying today, a long, long day, |

naganagashi hi o |

|

till dusk again makes its end. |

kyō mo kurashitsu |

|

Mitsune |

CONTEXT: Ki no Tsurayuki (872?–945) and Ōshikōchi no Mitsune were both minor court officials who served as compilers for Kokinshū and were known primarily as poets. Teijiin uta-awase (Retired Emperor Uda’s poem contest, 913) was sponsored by two princesses, each leading a team (called left and right, following the standard pattern), and the event involved music, fine costume, and the display of “landscape trays” as well as poems. The contest was a social and ritual event held at rooms in the imperial palace, where the poems—eighty of them, in forty rounds—were recited aloud in formal fashion by appointed ladies and final “judgments” (han no kotoba or hanshi) were rendered by Emperor Uda himself. The broad topics for the event were spring, summer, and love.

COMMENT: Tsurayuki’s poem plays against the technique of “confusion of the senses” by challenging conventional metaphors in the light of real experience, using a transparent conceit to do so. For we must notice, he proclaims, that the wind blowing through the blossoms in spring is not a cold winter wind; and do we not see that blossoms scattering against a spring backdrop are quite unlike snow flurries in the pallid skies of winter? The poem is a superb example of the rhetorical polish and playfulness associated with the Kokinshū style, which was heavily influenced by the witty poetry of the Six Dynasties era in China (220–589). It is also an example of a poem that went through recycling, appearing in the spring book of the third imperial anthology, Shūishū (Collection of gleanings [1005–1007]; no. 64).

Poetry contests—one of the first modes of “publication” in the early days of the tradition—were often spectacles first of all, where the win was awarded on the basis of technical mastery rather than artistic excellence. In this case, a note tells us that the judgment went against Mitsune because of his use of the somewhat archaic phrase naganagashi hi (literally, “a long, long day”), which we are told made the “reader” shrug her shoulders and mumble when reciting it. Such things were called yamai, poetic “ills” or “faults.”

MIBU NO TADAMINE 壬生忠岑, Kokinshū 625 (Love): “Topic unknown”

|

Since that parting |

ariake no |

|

when I saw your cold rebuff |

tsurenaku mieshi |

|

in the late moon’s glare, |

wakare yori |

|

nothing is more cruel to me |

akatsuki bakari |

|

than the moment of dawn. |

uki mono wa nashi |

CONTEXT: Mibu no Tadamine (fl. 905–950) was a courtier who wrote an influential poetic treatise and served as one of the compilers of Kokinshū. His poem is a classic variation on the “morning-after” (kinuginu) subgenre, the speaker being a man who is now complaining either about being rebuffed altogether or about a tryst that ended too soon. The poem was later included (as poem no. 30) in Ogura hyakunin isshu (One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets, ca. 1235) and many other collections.

COMMENT: Love as a poetic dai is generally portrayed as fraught with yearning (in the beginning) and resentment (later); little attention goes to joyful consummation. Tadamine’s conception employs personification, relying on the metaphor of the cold visage of the remaining moon—the so-called ariake no tsuki, which rises late in the latter half of the lunar month and remains in the sky at dawn—as a symbol of rejection. To express his idea, Tadamine employs a central pivot structure that an English translation can only suggest: the phrase tsurenaku mieshi (appearing distant, cold, unresponsive) modifying both “the moon” as a predicate and “parting” as an attributive clause. Thus we imagine a man on his way home at dawn (a dominant trope in love poetry) looking up at the moon, only to see reinforcement of his unhappiness in its cold light.

It was probably the metaphor of the dawn moon gesturing toward the complex but unarticulated feelings of rejection over time that made the author of Teika jittei (Teika’s ten styles)—an influential text of uncertain date attributed to Fujiwara no Teika (1162–1241), probably falsely, we know now—single Tadamine’s poem out as one of only several poems from Kokinshū that qualified as examples of the ideal of yūgen, or “mystery and depth” (p. 362). Interestingly, one of the others (Kokinshū, no. 691) on that same list for that same category (p. 364), by the monk Sosei (d. 910?), is similar to Tadamine’s.

|

Because you pledged |

ima komu |

|

that you would come at once, |

to iishi bakari ni |

|

I waited all night— |

nagatsuki no |

|

in the end greeting only |

ariake no tsuki o |

|

the moon of a Ninth Month dawn. |

machiidetsuru kana |

Here rather than the man going home on the morning after a tryst, we have a woman waiting for a man who never shows. It is common in Japanese poetry for a man to speak as a woman, or vice versa. Classical Japanese poems present no linguistic gender marking, nor do they use honorific or humilific language that would reveal class relationships. Ironically, this made it easier for a man to speak as a woman, or vice versa.

ANONYMOUS, Kokinshū 1027 (“Haikai” chapter): “Topic unknown”

|

You, scarecrow, |

ashihiki no |

|

standing in a rice paddy |

yamada no sōzu |

|

in foot-wearying hills: |

onore sae |

|

what a bother to be wanted |

ware o hoshi chō |

|

by even such as you. |

urewashiki koto |

CONTEXT: Kokinshū is made up primarily of thirty-one-syllable, formal waka, but its last two books contain a few chōka, folk songs, and haikai no uta, or “eccentric poems.” We know nothing of the specific circumstances of the rather rustic poem here. One imagines a young woman as the speaker—someone so popular that she mistakes a scarecrow for a man in pursuit. Personification and apostrophe were prominent Kokinshū-era techniques.

COMMENT: Half the haikai poems in Kokinshū are anonymous, but we also have haikai by prominent poets such as Tsurayuki, and we can assume that most poets occasionally produced humorous works. The humor in early haikai no uta tends to be light and usually involves mainstream images, as is the case with the following poems on cherry blossoms from Goshūishū (Later collection of gleanings, 1203–1209; nos. 1201 and 1207) by the courtier Fujiwara no Sanekata (d. 998) and a monk named Zōki (also known as Ionushi).

“Topic unknown”

|

Perhaps a few blossoms |

mada chiranu |

|

have not fallen yet, I think, |

hana mo ya aru to |

|

and set off to see. |

tazunemin |

|

But we best be quiet a bit— |

anakama shibashi |

|

we mustn’t let the wind know! |

kaze ni shirasu na |

“Composed when the winds began to blow after blossoms had fallen in his courtyard”

|

I had thought |

ochitsumoru |

|

to go see blossoms piled up |

niwa o dani tote |

|

in my courtyard. |

miru mono o |

|

How heartless of the storm winds |

utate arashi no |

|

to be sweeping them away! |

haki ni haku kana |

Seven of the twenty-one imperial anthologies include small sections of eccentric poems. Later, in the medieval period, poets would produce comic poems involving bawdy subject matter—what we refer to as kyōka—although the term haikai no uta persisted. In common parlance, the term haikai now usually refers to the Edo-period precursor of haiku.

MURASAKI SHIKIBU 紫式部, “Matsukaze” (The wind in the pines) chapter of The Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari 2: 393–94)

At dawn, as departure loomed ahead, there was a chill in the autumn wind and insects were busily crying.… Wondering how he would fare alone, the monk was unable to control his feelings.

|

As we part ways, |

yukusaki o |

|

I stop and look down the road |

haruka ni inoru |

|

with a hopeful prayer. |

wakareji ni |

|

Yet still I am an old man |

taenu wa oi no |

|

who cannot stay his tears. |

namida narikeri |

|

The Akashi Monk |

|

|

Will we both live on |

ikite mata |

|

to someday meet again? |

aimimu koto o |

|

And if we do—when? |

itsu tote ka |

|

For now, I can only trust |

kagiri mo shiranu |

|

in a future yet unknown. |

yo o ba tanomamu |

|

The Akashi Lady |

|

CONTEXT: Murasaki Shikibu (precise dates unknown), lady-in-waiting to an empress, wrote all the poems in The Tale of Genji herself, always from the dramatic perspective of the characters in her stories. In this case we have poems exchanged by the Akashi monk and his daughter. The occasion is her departure for the capital to enter Genji’s household, which means leaving her father behind. The most common form of exchange poem (zōtōka) was a “morning-after” poem (kinuginu), referring to a message sent by lovers after a night together, but many other occasions also elicited poems.

COMMENT: Corresponding through poetry was a requirement of life for both men and women at court. Here we have an exchange from The Tale of Genji involving not lovers but a father and child. Although the old man had always dreamed of his daughter’s joining high society, there is inevitably sadness as they part—she to begin life as one of Genji’s consorts in the city, he to dedicate himself to Buddhist devotions that he has postponed too long.

The imagery of the poem is what we might expect: without the mediation of a natural image, we see two people looking down the uncertain road ahead. Conceptually, the “parting of the ways” of the first poem is balanced by “meet again” in the second. Fittingly, we note the prayer of a father followed by a daughter’s avowal of faith in the future. The old man’s prayers for her future had been realized in Genji’s advent in Akashi, after all; why should the gods not continue to smile on her in Kyoto? The speakers could not know what readers would learn: that one day the child that was the product of Genji’s time in Akashi would become empress, or that, as both feared when writing their parting poems, the monk and his daughter would indeed not meet again.

FUJIWARA NO KINTŌ 藤原公任, Senzaishū 1203 (Buddhism): “Like floating clouds”

|

We liken ourselves— |

sadame naki |

|

our bodies, frail and vagrant— |

mi wa ukigumo ni |

|

to floating clouds. |

yosoetsutsu |

|

And all along, in the end, |

hate wa sore ni zo |

|

that is what we shall become. |

narihatenu beki |

CONTEXT: Fujiwara no Kintō (966–1041) was a poet and court officer who was also one of the most honored scholars of his day. His poem appears in the seventh imperial anthology, Senzaishū (Collection of a thousand years, 1188), in the chapter dedicated to Buddhist poems (shakkyōka), a subgenre that remained important for centuries. Earlier we encountered Buddhist concepts and paradigms at work in a number of poems, those by Murasaki Shikibu, most obviously. The category had first been separately designated in poetry collections at the end of the eleventh century. At first such poems were included under the heading “Miscellaneous” but later appeared in a separate chapter of their own.

COMMENT: Shakkyōka were written in many different contexts: on visits to temples, at gatherings associated with religious services, or for votive sequences, to name a few. Although we lack background information about Kintō’s poem, scholars point out a relevant passage of scripture in the Vimalakirti Sutra (ca. 100 CE) that lists metaphors for the body, including clouds but also other insubstantial things—dreams, reflections, bubbles on water, echoes, and so on. So common is that kind of metaphor that one might hesitate to cite a particular source were it not for the headnote, which indeed reads like a quotation. Writing poems on passages from scripture was common practice.

As a general context for the poem one must remember that at the time bodies were usually cremated. There were several sites on the outskirts of Kyoto, most notably Toribe Fields, where bodies were burned, thus quite literally becoming “clouds” of smoke. Cleverly, Kintō makes this the overt theme of his poem, which is how a metaphor we often use to describe the frail nature of our bodies and the uncertain qualities of human existence will “in the end” emerge as a literal truth, consonant with the concept of ephemerality, the most basic of all Buddhist teachings. From the beginning, our bodies are fated for decline and death, prey to illness, accident, old age, and ultimate mortality, thus being sadame nashi, “impermanent”; and after our mortal frames have been reduced to smoke, leaving only a few bones behind as relics, nature seems to be giving us a lesson by converting our remaining energy into a cloud to be tossed on the wind, briefly, before being absorbed into the “nothingness” of the sky. (The same Chinese character is in fact used for both “nothing” and “sky”—the first variously read as kara, aki, munashi, and kū, and the second as sora—producing an ironic lexical situation in which the idea of “empty” is “full” of connotations.) Here the word “sky” does not appear, but it is inevitably in the background whenever the “cloud” is used, being the final destination for all the insubstantial elements of worldly existence.

ANONYMOUS, Wakan rōeishū 571: “House in the paddies”

|

Wasn’t it yesterday |

kinō koso |

|

we transplanted our seedlings? |

sanae torishi ka |

|

And yet already |

itsu no ma ni |

|

the leaves of the rice plants rustle |

inaba mo soyo ni |

|

in passing autumn wind. |

akikaze no fuku |

CONTEXT: As already noted, Chinese poetry was composed in Japan from the earliest times. The first three imperial anthologies produced at the Japanese court, dating to early in the ninth century, in fact consisted of Chinese poems exclusively. A later anthology, Wakan rōeishū (Songs in Japanese and Chinese, ca. 1018) offers a contrast by including Chinese poems (kanshi) written by both Chinese and Japanese poets, along with waka by the latter as well. Rather than full Chinese poems, however, Kintō, who put the work together, excerpted just a few lines (usually two), while in contrast quoting waka in full. All the poems in the book, whether in Chinese or Japanese, were evidently sung, whether privately or in groups, according to melodies then known in literate society that we can only guess at now. Most of Kintō’s poets are canonical figures, from the works of the late Tang dynasty in China and the ninth and tenth centuries in Japan. The poem here actually appeared first in Kokinshū (no. 172), as did many of the poems in the anthology.

COMMENT: Kintō often recontextualized poems—i.e., put them under subject categories that do not correspond to their original contexts. The poem included here, for instance, appears in Kokinshū among poems on the conventional dai of “autumn wind,” rather than under the dai “house in the paddies.” A slight difference, one might say; and perhaps assuming anything about an anonymous poem with no headnote is risky. Yet the fact remains that the new heading directs our mental gaze to farmers living in shacks in the fields rather than the more “elegant” themes of the breezes blowing over the leaves on the rice plants and the imperceptible passage of time. Two Chinese lines (Wakan rōeishū, no. 566) by Miyako no Yoshika (834–879) included under the same heading make the contrast even more clear.

Guarding the house, a dog barks at a visitor;

grazing in the fields, cows lead their calves to rest.

As a doctor of letters at the imperial court, Yoshika wrote poems in proper Chinese, with proper Chinese themes and images. Among them were dogs and cows, thought to be too rustic for courtly treatment in waka. Many of the poems in Wakan rōeishū appear under subject headings not unlike those found in Japanese anthologies—plum blossoms, travel, pines, year’s end, and so on. Others, however, resonate more with Chinese traditions—pleasure girls, friends—or neighbors, as we see in a few lines (no. 573) by Bai Juyi, who is credited with more poems than any other poet in the anthology.

Not alone but together, we shall stay till life ends—

and leave a fence for our progeny to share.

FUJIWARA NO KIYOSUKE 藤原清輔, Shin kokinshū 1843 (Miscellaneous): “Topic unknown”

|

If I should live on, |

nagaraeba |

|

may I yet recall these days |

mata kono goro ya |

|

with tender feelings? |

shinobaren |

|

Those times I thought hard long ago |

ushi to mishi yo zo |

|

are fond memories to me now. |

ima wa koishiki |

CONTEXT: Fujiwara no Kiyosuke (1104–1177) was a prominent poet who is now remembered more for his scholarship and activities as a critic and contest judge. The headnote to this poem in his personal anthology says only that Kiyosuke sent the poem to someone “when he [Kiyosuke] was thinking about the past.” It is interesting to note, however, that the poem later went through recycling three times: first, for inclusion in his own personal poetry collection (shikashū) of more than four hundred poems, put together late in his lifetime, by the poet himself or someone working from his records; then for the eighth imperial anthology, Shin kokinshū (New Collection of Ancient and Modern Times, ca. 1205); and finally for the most famous of all small Japanese poetic anthologies, the Ogura hyakunin isshu (no. 84). Compiled by Fujiwara no Teika in 1216 at the request of a patron, the latter collection would become a primer for practitioners of the waka form for centuries to come. It has the distinction of being perhaps the most popular of all poetic texts in premodern times.

COMMENT: Natural imagery is a component of most waka, but not all. Here Fujiwara no Kiyosuke presents a logical proposition that is in no way dependent upon the “outside” world for its power. He deploys a common two-part structure, with the caesura at the end of the third line, in a riddle-like rhetorical posture, asking, “Why might I later recall the present with positive feelings?” and answering, “Because in time our troubles are covered over by nostalgia, making even the hardest times seem dear.” As readers we look first into the future, then move from the present—a time of trouble, we later learn—into another time of trial in the past, and then back to the present, but with a new understanding. Ultimately, though, what we learn is less logical than psychological, which explains why Teika jittei (p. 368) would later honor it as an example of ushin (deep feeling), a quality of affective richness that Teika felt all proper poems should display. The process described is therefore a reasoning process, while the conclusion goes beyond that to express sentiment.

In Ogura hyakunin isshu Kiyosuke’s poem is surrounded by laments, a fact that has perhaps tinted interpretations too much over the years. For, in addition to being a lament, the poem is also a pronouncement on the nature of memory. The reader must assume some kind of crisis behind the poem, either for Kiyosuke or the person to whom he sent it (a male relative, the commentaries say), which makes the poem personal on the surface. Significantly, however, we are not told the source of the sadness. A failing love affair, perhaps? Illness? Political conflicts? Disruptions in the natural order? No answer is given, perhaps purposely so. To restrict the poem’s scope by being more specific would reduce its power for readers as an insight of universal significance.

TOMOTSUNE 智経, Hirota no yashiro uta-awase 53 (round 27): “Snow in front of a shrine”

|

I shall not trespass |

tamagaki no |

|

the jeweled fence of the shrine. |

uchi e wa iraji |

|

Surely the god, too, |

furu yuki o |

|

would resent any footsteps |

fumimaku oshi to |

|

on this newly fallen snow. |

kami mo koso mire |

CONTEXT: Tomotsune is identified as a priest in an early document. He probably was associated with Hirota Shrine, which still stands today in Hyōgo Prefecture, near the city of Nishinomiya (literally, “western shrine”). According to legend, the shrine was established by the decree of Empress Jingū in the 300s, upon command of the Sun Goddess, Amaterasu. It was one of the Twenty-Two Shrines of the Home Provinces to which offerings were sent by the imperial court at a festival held during the Second and Seventh Months to pray for a good harvest. Shinto shrines were as important as Buddhist temples in the world of medieval Japan and were often located in old-growth groves that were themselves considered sacred, serving as the earthly abodes of deities. To emphasize their antiquity, shrine buildings were kept simple, even rustic, but every effort was made to keep both buildings and grounds clean, reflecting the fact that one of the chief occupations of priests presiding there was purification rituals.

COMMENT: A curious story lies behind the decision to hold a poetry contest at Hirota Shrine—referred to as just that Poetry Contest at Hirota Shrine—in 1172. Two years before, a large event of eighty-seven rounds involving all the major poets of the day, including courtiers, court ladies, and clerics, had been held on Osaka Bay at Sumiyoshi Shrine, which made the god of Hirota so envious, so the story goes, that he expressed his displeasure in a dream that was reported to a monk—who then decided to hold a similar event at Hirota to assuage the spirit of the god. The format of the contest was identical to the one held at Sumiyoshi, involving most of the same poets, dai, and the same judge, Fujiwara no Shunzei.

The circumstances of the contest are perhaps suggested by Tomotsune’s poem, in which he explicitly expresses a desire not to offend the god. The central idea of the poem, however, perhaps owes more to literary precedent, especially a poem by Izumi Shikibu (precise dates unknown) from Shikashū (Collection of verbal flowers, ca. 1151–1154; no. 158) in which she tries to convince herself that it is just as well she is not visited by a tardy lover, “not wanting footsteps to disturb / the snow of my garden court.” This explains Shunzei’s comment in awarding the poem a win in its round: “Nothing new in conception, but still elegant and refined [yū], I should think.” The poet’s reluctance to sully the beauty of the shrine precincts reveals a proper courtly sensibility, as well as religious devotion, of course; but as we imagine the speaker standing outside the fence, looking in on the grounds in reverie, we also naturally think of the precincts as a sacred space made more so by a layer of pure white snow, a place in which the aesthetic and the spiritual merge together. That it was associated with the most important of all native gods, the Sun Goddess, imbued the poem with an additional layer of cultural significance.

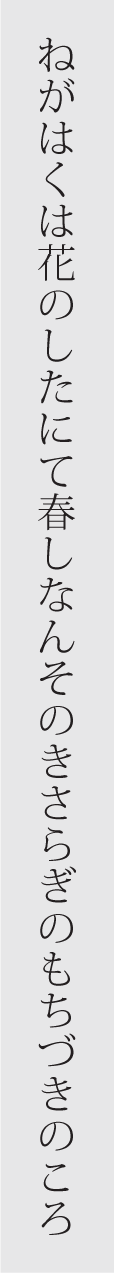

SAIGYŌ 西行, Sankashū 77 (Spring): “From his many poems on ‘blossoms’ ”

|

If I had my wish, |

negawaku wa |

|

I would die beneath the blossoms |

hana no shita nite |

|

in the springtime— |

haru shinan |

|

midway through the Second Month, |

sono kisaragi no |

|

when the moon is at the full. |

mochizuki no koro |

CONTEXT: Saigyō (1118–1190) was a samurai in the Guards Office of the retired emperor before becoming an itinerant monk in his twenties. He died as he wished, on the sixteenth day of the Second Month.

COMMENT: This poem from the poet’s personal collection, Sankashū (Mountain home collection, precise date unknown), also appeared in a mock-poem contest, the Mimosusogawa uta-awase (The Mimosusogawa poem contest, 1189), which Saigyō submitted to Shunzei, whose comment on the poem is famous: “This poem is anything but beautiful in outward effect, but for its style it works well. Yet a person who has not gone far along the way will not be up to composing in this manner. This is something that can be achieved only after a poet has arrived at the highest level” (Mimosusogawa uta-awase 13).

The poem is terse and direct, without adornment, colloquial, and didactic—indeed, as Shunzei says, not beautiful (uruwashi) in total effect (sugata). The aesthetic term often used to describe such works is heikaitei, “ordinary” or “plain,” and it is used in a negative sense by Shunzei himself, as well as by Retired Emperor Juntoku (1197–1242) and other medieval critics. In Saigyō’s case, however, the direct style succeeds in expressing the ultimate religious desire—to die at the same time of year as the historical Buddha—in terms of two premier icons of the courtly tradition, cherry blossoms and the moon. He believed in the spiritual efficacy of waka, in “purifying the heart, eliminating evil from one’s thoughts” (Saigyō shōnin danshō [Conversations with Saigyō], ca. 1225–1228, p. 271).

Another poem shows that Saigyō could produce poems of conventional beauty and skill. This one (Shin kokinshū, no. 1615) was written when he saw Mount Fuji while on the road:

|

Following the winds, |

kaze ni nabiku |

|

smoke rises from Fuji’s peak |

fuji no keburi no |

|

into empty sky, |

sora ni kiete |

|

its destination unknown— |

yukue mo shiranu |

|

as too my vagrant passions. |

waga kokoro kana |

Here Saigyō employs a jokotoba in which the first three or four lines of the poem provide a figurative correlative for the idea expressed at the end: “Smoke rising from a peak and then fading off into the sky, at the mercy of the winds,” he says, “that is what love is for me.” Fuji had been on the list of poetic meisho (or nadokoro, “famous places”) for hundreds of years and remains an icon of Japanese culture today. This poem is listed in Teika jittei (p. 366) as an example of the taketakakiyō (the lofty style), in direct contrast to the heikaitei.

PRINCESS SHIKISHI 式子内親王, Shin kokinshū 1124 (Love): “From among the poems of a hundred-poem sequence”

|

Oh, I am aware |

yume nite mo |

|

that I may appear in his dreams— |

miyuramu mono o |

|

but what of my sleeves? |

nagekitsutsu |

|

Will he see these wet sleeves, tonight, |

uchinuru yoi no |

|

as in sadness I lie down? |

sode no keshiki wa |

CONTEXT: Princess Shikishi—formally Shikishi Naishinnō (d. 1201)—served as Kamo Virgin in her youth, but after a decade resigned because of illness, thereafter living a somewhat reclusive life. In 1197 she became a nun. She was among those requested by Retired Emperor Go-Toba (1180–1239) to present a hundred-poem sequence in the autumn of 1200. She died very soon after and never saw her poem honored in Shin kokinshū.

COMMENT: Princess Shikishi’s poem is an example of how the subject of love is often figured through a contrast between the dream world and the world of reality. We can assume that the speaker is not so much Shikishi herself, who was a nun at the time, as a rhetorical extension of herself based on literary precedents and her own experience in the highly codified culture of the imperial court. Writing on dai (in this case, love) demanded that one express an idea, usually through a particular and private experience.

Still, though, she was a woman. The setting of the poem is nighttime, when a woman is yearning for a lover whose identity is undisclosed. Perhaps he had promised to visit; perhaps she waits only for a message. In either case she is left alone, musing that while tonight they may not meet in the real world, perhaps she will appear to him in his dreams. Even if she does, however, she stresses that he will not see the reality of her situation. “And suppose I do appear in his dreams,” she says, “will he see me the way I am now—my sleeves drenched with tears?” The rhetorical question suggests that what the man sees will likely be only an extension of his own romantic fantasies. The reality would be more unpleasant: a woman grieving as she gives in and goes to bed, her sleeves showing her distress. The sleeves are a synecdoche for an entire body wracked with heartache.

In coming years Princess Shikishi would figure in the tradition as the court lady par excellence, evoking effusions like the following from Kirihioki (The paulownia brazier, p. 287), a text spuriously attributed to Teika but written well after his death: “How should one describe her poems? A courtier, his countenance rosy and glowing, dances ‘The Waves of the Blue Ocean’ below the palace steps as autumn leaves fall, his hair adorned with a chrysanthemum beginning to fade.” Such a highly romanticized vision, harking back to the image of the ideal Heian-era courtier, Genji, who danced the same dance in the “Beneath the Autumn Leaves” chapter of The Tale of Genji, is perhaps the sort of thing Shikishi is actively resisting in her poem. She includes no mention of color, or scent, or sound, and even the image of tears drenching her sleeves must be inferred from context. It is also significant that the metaphor reverses her gender, while aestheticizing it at the same time.

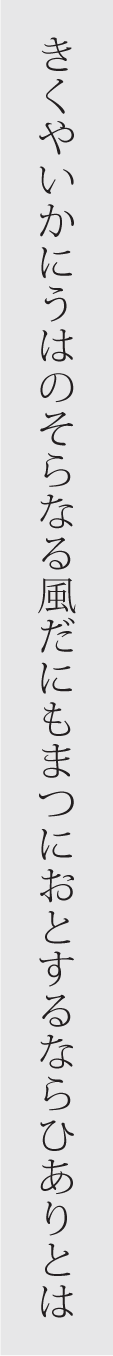

LADY KUNAIKYŌ 宮内卿, Shin kokinshū 1199 (Love): “Love, using ‘wind’ to express longing”

|

Do you not hear it? |

kiku ya ika ni |

|

Even the fickle wind that blows |

uwa no sora naru |

|

in the sky above |

kaze dani mo |

|

is sure to sound its coming |

matsu ni oto suru |

|

to the waiting pines. |

narai ari to wa |

CONTEXT: One of Go-Toba’s consorts, Kunaikyō died only a few years after she wrote this poem, still in her twenties. Fifteen of her poems ended up in Shin kokinshū. She was among ten poets invited by the retired emperor to participate in a contest in the autumn of 1202, dai for which were sent out on the twenty-ninth of the Eighth Month, with a formal “airing” and judgment taking place at Go-Toba’s Minase Palace two weeks later—the so-called Minasedono koi jūgoshū uta-awase (The fifteen-poem contest at Minase Palace). At that time, Shin kokinshū was being compiled and poets did their utmost to produce poems worthy of inclusion in the imperial anthology.

COMMENT: In judgments attached to the contest, Lady Kunaikyō’s poem received high praise from both Go-Toba and Fujiwara no Shunzei, the latter calling it “excellent in both idea [kokoro] and diction [kotoba], from beginning to end” (Minasedono koi jūgoshū uta-awase, no. 141). She begins with an enigmatic question to a negligent lover: “How can you not hear what I hear?” Then the speaker answers the question by referring to something the lover must hear too: the wind, which despite its reputation for caprice, can still be relied upon (the Japanese is narai ari, “to be in the habit or custom of”) to let the pines know, through its sound, that it is coming for a visit. As a message, then, the poem says simply, “You are less reliable even than the wind. How long must I wait?” Readers (of the Japanese original, at least) would recognize the presence of two kakekotoba: matsu, meaning both “pine tree” and “waiting,” and otosuru, meaning both “announce” and “visit.” Also working as a double entendre is the phrase uwa no sora (the sky above), which when modifying the “wind” means “fickle.”

Despite its rhetorical complexity, the poem is graceful both aurally (the full vowel sounds of uwa no sora naru at the center of the poem contrasting well with the more staccato sounds before and after, leading up to a final emphatic and rising wa) and syntactically, thus displaying the qualities held to be essential for poetic excellence. Altogether, it is a fine example of the ideal of the “clever style” (omoshirokiyō). But Kunaikyō’s poem is more than just clever. As Go-Toba remarks, “It is the skillful use of the ‘wind’ to articulate the dai that makes the poem” (Wakamiya senka-awase [Wakamiya contest of selected poems] 1202; no. 27). Along with the speaker, we sit inside at night, listening (not seeing: the poem is all sound) to the wind in the pines, anxious for a visitor or at least a messenger. But as the hours go by the wind signifies only disappointment. Anticipation turns to bitterness, and we pine with the pines, listening in the darkness to sounds that inspire more annoyance than hope. The psychological state of the speaker is thus as intricate as Kunaikyō’s rhetoric.

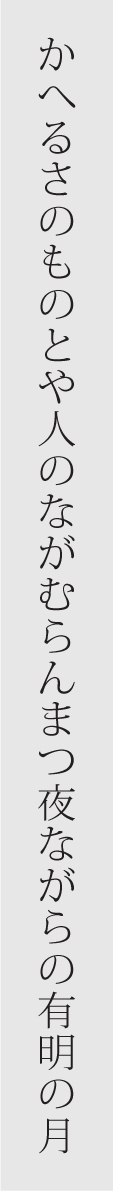

FUJIWARA NO TEIKA 藤原定家, Shin kokinshū 1206 (Love)

|

After his tryst, |

kaerusa no |

|

he may think it lights the way |

mono to ya hito no |

|

as he returns home. |

nagamuran |

|

But I gaze at it, still waiting— |

matsu yo nagara no |

|

there in the dawn sky, the moon … |

ariake no tsuki |

CONTEXT: Teika, son of Shunzei, is known for his interest in aesthetics generally and, in his own poetry, for complex rhetoric and use of symbolism. Here we have a poem of the sort that might appear in a court romance. In another poem that involves gender reversal, a woman gazes up at the moon after waiting all night for a man who never came, a man whom she imagines going home, oblivious to her loneliness, after visiting a rival. The moon in the sky at dawn is that same moon that served as a symbol of rejection for Mibu no Tadamine. Indeed, it seems likely that Teika wants us to remember Tadamine’s poem, which Teika later recontextualized for his anthology Ogura hyakunin isshu (no. 30).

COMMENT: In Japanese, Teika’s poem reverses normal syntax by ending not with a verb but with a noun (a rhetorical technique called taigendome), creating an unresolved effect popular among poets of the generation of Shin kokinshū and on into the late medieval era. The romantic, evocative quality of the poem makes some scholars see Teika’s poem as an example of the ideal of yōen, or “ethereal beauty,” a term that Teika used only a few times and never really defined. What’s more, when the poem appears in Teika’s list of poems in various styles, it is offered as an example of the ideal of Teika’s later years—ushin, or “deep feeling.” (Frustratingly, the yōen style is not included in that list at all.) Since Teika elsewhere says that the quality of “deep feeling” is one that should be present in all styles, the problem is not insurmountable. But the confusion does serve as a caution against reducing our understanding of Japanese poetry to an exercise in mechanically applying aesthetic ideals to poems. A poem by Juntoku (Juntokuin onhyakushu [The one-hundred-poem sequence of Retired Emperor Juntoku] 1237; no. 5) that Teika in a short interlinear note does praise as an example of yōen presents something closer to Shunzei’s ideal of en, or “loveliness”:

|

I wake from a dream, |

yume samete |

|

and through the gaps in blinds |

mada makiagenu |

|

not yet rolled up, |

tamasudare no |

|

it seeks its way into my chambers— |

hima motomete mo |

|

the scent of flowering plum. |

niou mume ga ka |

There is no direct allusion of human drama here but only the delicate evocation of an elegant situation and an ingenious conception: we expect moonlight in the last line, but instead we get the scent of plum. One suspects, however, that Juntoku—and Teika reading Juntoku’s poem—may have been thinking of old traditions that associated plum scent with nostalgic feelings for departed loved ones.

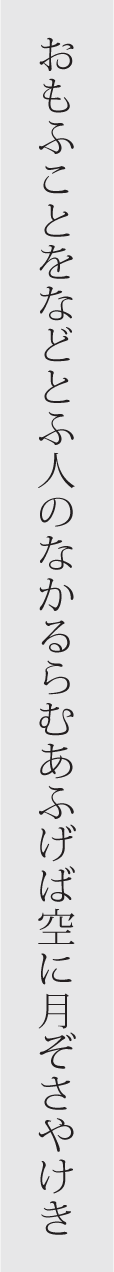

CHIEF ABBOT JIEN 慈円, Shin kokinshū 1782 (Miscellaneous): “From a fifty-poem sequence”

|

As I muse alone, |

omou koto o |

|

why does no one come to ask |

nado tou hito no |

|

what is troubling me? |

nakaruramu |

|

I look up, and in the sky |

augeba sora ni |

|

the moon is shining bright. |

tsuki zo sayakeki |

CONTEXT: Jien (or Jichin, 1155–1225) was the son of a regent and himself became the chief abbot of the Tendai sect, most powerful of the aristocratic sects of Buddhism at the time. The poem here was composed for a poem contest titled Rōnyaku gojisshu uta-awase (Contest of fifty poems, between the old and the young) convened by Retired Emperor Go-Toba early in 1201. The first step in the process was the composition of fifty-poem sequences by the ten participants, which were then paired for the contest of two hundred fifty rounds. Jien, at age forty-seven, was on the “old” side. His poem was on the open dai of “miscellaneous,” which gave poets considerable latitude in choosing imagery. Strictly speaking, the image of the moon would denote an autumn setting, but seasonal description is obviously not the main focus of the poem.

COMMENT: The upper half of Jien’s poem is a simple statement of loneliness. We are not told what the speaker is brooding about, only that he wishes someone would come and allow him to unburden himself. The last two lines then give him—and his readers—a reply. In his loneliness, he looks up at the sky and sees the moon shining bright. In this case the brightness (sayakesa) is crucial to our understanding. One need only remember the cold glare of the moon in Tadamine’s famous poem to conclude that in Japanese poetry the moon does not always offer comfort. But here the brilliance of the moon seems to be answering Jien’s query. As scholars point out, the moon shining bright is described in Buddhist discourse as the shinnyō no tsuki, “the moon of truth.” Since the compilers placed Jien’s poem in the “Miscellaneous” book of Shin kokinshū rather than in Buddhism, they must have judged it to be less an attempt at doctrinal statement than a poem of praise about the beauty of the moon shining in worldly gloom. It is not surprising, however, that Jien turned to a Buddhist conception for his theme. Several years before, he had been replaced as chief abbot because of political conflicts, but he would be reappointed at Go-Toba’s bidding just a few days after the first of the gatherings for the contest took place.

In several medieval lists this poem is offered as an example of the “lofty style” (taketakakiyō). One wonders if this is partly because early readers immediately identified the speaker with Jien himself, a man of the highest rank and aristocratic attainments. More than anything else, however, it is the elevated diction of the poem and its sense of grandeur that put it in that exalted category. Rhetorically the lines of the poem take us from the gloom of the speaker’s mind up into the sky, and then into the light. The way the upper and lower halves of the poem related to each other not through word association but through suggestion and feeling qualified the poem in the mind of the renga master Shinkei (1406–1475) as an example of soku, or “distant linking,” as explained in his Sasamegoto (Whisperings, 1463–1464, p. 122).

FUJIWARA NO IETAKA 藤原家隆, Minishū 1776 (Winter): “ ‘Snow in the pines,’ from a fifty-poem sequence at the house of the Reverend Prince Dōjō”

|

At Takasago |

takasago no |

|

the days go by without cries |

onoe no shika no |

|

from deer on the slopes— |

nakanu hi mo |

|

days that pile up with white snow |

tsumorihatenuru |

|

enveloping the pines. |

matsu no shirayuki |

CONTEXT: Fujiwara no Ietaka (1158–1237) was a regular in the court of Retired Emperor Go-Toba. Like Teika, he served as a compiler of Shin kokinshū.

COMMENT: Poetry in the waka form is highly intertextual in the sense that it uses fixed lines and phrases that inevitably gesture back toward scores of other poems. But from early in the tradition poets also used a device called, literally, “taking a line from a foundation poem” (honkadori). The practice began very early but was particularly conspicuous among poets of the Shin kokin age. It was applied in diverse ways, with poets sometimes appropriating only one prominent phrase, sometimes as much as three full lines. Ietaka’s poem is an example of the latter, taking three lines (the first three in the foundation poem, which become the last three in the later poem) from an anonymous poem from Shūishū (no. 191), written two hundred years before.

|

Again and again |

akikaze no |

|

the winds of autumn blow |

uchifuku goto ni |

|

at Takasago— |

takasago no |

|

where no day goes by without cries |

onoe no shika no |

|

from deer on the slopes. |

nakanu hi zo naki |

A first reading of Ietaka’s poem will focus on the clever way in which he “reverses” the earlier poem by changing just one syllable: takasago no onoe no shika no nakanu hi ZO [naki] becoming takasago no onoe no shika no nakanu hi MO [tsumori], which in the translation becomes “no day goes by” and “the days go by.” Beyond that, however, Ietaka has also changed the seasonal context, moving from autumn to winter. As a reader one cannot help but imagine the deer of the earlier poem hunkered down somewhere on slopes now covered with snow. Thus Ietaka invites us to hear those distant cries, along with the autumn wind, hovering behind his winter scene. In so doing, he suggests imagery and meaning that are the essence of what Shunzei called yūgen, “mystery and depth,” while also imbuing his scene with “deep feeling” (ushin). The Zen monk and poet Shōtetsu (1381–1459), speaking of layers of meaning, would say that Ietaka’s poem was itself the “deepest of all poems” (Kenzai zodan [Chats with Master Kenzai], before 1510?, p. 144). The call of the deer—figured as yearning for its mate—was considered especially moving. Ietaka makes it even more evocative by alluding to it only as an absence, in that way fully expressing the feeling of accumulating snow that obscures all.

EMPEROR TENCHI 天地天皇, Ogura hyakunin isshu 1

|

In autumn fields |

aki no ta no |

|

stands a makeshift hut of grass |

kariho no io no |

|

with its roof of thatch— |

toma o arami |

|

so roughly made that my long sleeves |

waga koromode wa |

|

are ever wet with dew. |

tsuyu ni nuretsutsu |

CONTEXT: Emperor Tenchi was the son of Emperor Jomei (593–641). As noted, succession disputes after his death eventually brought his brother, Emperor Tenmu, to the throne. His poem begins Fujiwara no Teika’s famous Ogura hyakunin isshu, the most famous of all hundred-poem sequences (hyakushu-uta), which dates from around 1216 and is thus a prime example of recycling. The Man’yōshū original (no. 2174), noted as anonymous, is on the dai of dew.

|

In autumn fields |

akita karu |

|

I’ve made a hut to live in, |

kariho o tsukuri |

|

while I harvest grain; |

waga oreba |

|

and so my long sleeves are cold, |

koromode samuku |

|

drenched as they are with dew. |

tsuyu zo okinikeru |

COMMENT: This poem has a messy history. The Man’yōshū version appears with a slightly altered first line as an anonymous poem in Shin kokinshū (no. 454). But the version Teika uses in his anthology comes from Gosenshū (Later collection, ca. 951; no. 302), the second imperial anthology, where it is listed as “topic unknown” and attributed to Emperor Tenchi, although he almost certainly did not write it. Prevailing opinion is that the final version dates from the Heian period, along with the attribution to Tenchi, reflecting his importance as the ancestor of all Heian-era emperors. The usual interpretation sees it not as a personal lament but as a didactic display of sympathy for farmers, but that idea probably also comes from Heian times.

The contrasts between the two versions tell us much about aesthetic ideals in Heian and later times. In the Man’yōshū version, the speaker constructs his own hut and alludes to actual work in the fields as his purpose, while the later version alludes directly to no such labor; nor does the later version say openly that the speaker “lives in” the hut, leaving that to suggestion, subtlety being a chief feature of late courtly ideals. Also, the Man’yōshū version says “sleeves are cold” directly, rather than hinting at that as in the newer version. Finally, there are syntactic breaks or pauses at the end of lines 2, 3, and 4 of the earlier version, while the Hyakunin isshu poem has only one break, at the end of line 3, which gives the poem the more elegant flow and rhythm of a formal poem (hare no uta). Thus the poem has been revised in a way that would have pleased representatives of later court ideals such as Teika’s father, Shunzei, who said that a good poem should have flowing aural qualities when read aloud and that it should be both elegant and moving (Korai fūteishō, p. 275). The revised version presents rustic subject matter, but in a more elegant and poignant way; and it eliminates choppy syntax in favor of a more smoothly flowing structure. A prominent medieval list of poems in aesthetic categories (Teika jittei, p. 363) lists the later version of the poem under yūgen, “mystery and depth.”

FUJIWARA NO TAMEUJI 藤原為氏, Shoku gosenshū 41 (Spring): “On ‘spring view of a cove,’ written in 1250 for a poem contest”

|

If someone asks me |

hito towaba |

|

I shall say I haven’t seen it— |

mizu to ya iwamu |

|

Tamazu Island, |

tamatsushima |

|

where haze spreads over the cove, |

kasumu irie no |

|

in spring, in the dim light of dawn. |

haru no akebono |

CONTEXT: Fujiwara no Tameuji (1222–1286) was son and heir of Fujiwara no Tameie (1198–1275), the latter being the sole compiler of Shoku gosenshū (Later collection continued, 1251), the imperial anthology in which the poem here appears. Tamazu Island was located off the coast at Waka Bay (now Wakayama Prefecture) and was the site of a shrine to one of the three gods of poetry, the other being Sumiyoshi Myōjin and Hitomaro.

COMMENT: The poet Tonna (1289–1372) records that the second line of this waka originally read, “I shall say I have seen it” and was changed to “I haven’t seen it” by Tameie himself, a small change (from mitsu to mizu in Japanese). Another anecdote, from Waka teikin (Teachings on poetry, 1326?, p. 139) explains, “Rather than describing in detail the features of Tamazushima, the poem seems replete with artistic atmosphere [fuzei] as the scene floats up before our eyes. It is the virtue of uta to reveal a surplus of meaning in just thirty-one syllables.… In poems with overtones [yojō], we see little technique on the surface, but as we recite them, we find more profound pathos and more loneliness.”

Leaving something to the imagination of readers is what constitutes the quality of yojō (also pronounced yosei) in this case, gesturing as it does toward an ineffable experience. And the effect is enhanced by an allusion to an anonymous Man’yōshū poem (no. 1215).

|

Tamazushima: |

tamatsushima |

|

be sure to observe it well. |

yoku mite imase |

|

What will you say |

aoniyoshi |

|

in Nara, place of rich earth, |

nara naru hito no |

|

when people ask what you saw? |

machitowaba ika ni |

Tameie’s death left his family in a fractured state. Tameuji was clearly his heir in the court hierarchy and inherited his titles, but his younger brothers challenged his authority. This conflict resulted in the splitting of the lineage into three branches: the Nijō descending from Tameuji; the Kyōgoku descending from Tamenori; and the Reizei descending from Tameie’s sons by his last wife, known as the Nun Abutsu (d. ca. 1283). This rivalry continued for more than a century, and the poetic issues it engendered for much longer than that. Yojō continued to function as ideal for poets in all those lineages, although more so for the Nijō than for the other lineages, and it would continue as an ideal in waka, renga, and haikai.

THE NUN ABUTSU 阿佛尼, Izayoi nikki (p. 195)

Mist was rising over waves breaking on the shore, concealing the many fishing boats on the water from view.

|

As if to declare, |

amaobune |

|

“You may not watch as fishing boats |

kogiyuku kata o |

|

ply the waters here!” |

miseji to ya |

|

waves rise and crest into mists |

nami ni tachisou |

|

at morning, out on the bay. |

ura no asagiri |

CONTEXT: Abutsu was a lady-in-waiting to an ex-empress in her youth who later became Fujiwara no Tameie’s wife and bore him several children. Izayoi nikki (Diary of the sixteenth night moon) relates how she traveled to Kamakura in 1279 in order to bring suit against Tameie’s formal heir, Tameuji, for withholding behests made to her sons. The poem above was written as she was arriving in Kamakura on the twenty-ninth day of the Tenth Lunar Month, just two weeks from her departure.

COMMENT: Travel poems are a staple of the court tradition, beginning even before Man’yōshū. Many among the nobility, high and low, traveled for official or private reasons, and pilgrimage too was an ordinary part of life. No wonder, then, that travel is a subcategory in even the earliest imperial anthologies (often subsumed under “Miscellaneous”) and a frequent dai in poetry contests and small anthologies. Our earliest major travel diary is Tosa nikki (Tosa Diary, 935) by Ki no Tsurayuki, and from his time until the end of the nineteenth century hundreds of other writers left such works. Some record mostly poems, composed at well-recognized meisho, while others include substantial bodies of prose. The travel diary of the Nun Abutsu presents a well-balanced mix. She documents thoroughly her journey along the most well-traveled road of the time, writing poems at all the places required by tradition, and concludes with a fairly lengthy description of her life in Kamakura, where she apparently stayed until her death a few years later.

We therefore know that the bay in this poem is at Kamakura and that the boats we see are mostly fishing boats. As the government seat of the shogun and his administrators, established nearly a century before, Kamakura was a bustling place, full of temples, shrines, government offices, residences grand and small, and shopping districts. Abutsu’s description shows us not such less-than-elegant and “worldly” sights, focusing rather on a vague view of mists on the sea, which she accuses of actively thwarting any desire she might have to see more of the boats at work. In this way we are denied any view of the labor of the boatmen, instead confronting a pastoral that shows the forces of the natural world colluding to restrict our vision: we continue to gaze out, but further details are left to the imagination. Abutsu’s reasons for traveling to Kamakura were worldly, indeed political for the most part, but her poems seldom allude to such matters in any direct way, except in how they establish her bona fides as a poet attempting to secure a place in court society for her sons.

LADY SAKUHEIMON’IN 朔平門院, Gyokuyōshū 719 (Autumn): “From among her poems on ‘the moon’ ”

|

In the growing light |

shiramiyuku |

|

of an ever whitening sky, |

sora no hikari ni |

|

its rays fade away |

kage kiete |

|

and leave only its silhouette— |

sugata bakari zo |

|

the moon lingering at dawn. |

ariake no tsuki |

CONTEXT: Sakuheimon’in (1287–1310) was a daughter of Emperor Fushimi’s (1265–1317) who died in her early twenties and left only a handful of poems. As a member of Fushimi’s family, however, she was involved in an important literary faction, the so-called Kyōgoku school, sponsored by Fushimi and the people around him. Gyokuyōshū (Collection of jeweled leaves, 1313), fourteenth of the imperial anthologies, enshrines their efforts.

COMMENT: The rhetorical tendencies of the Kyōgoku school are apparent here in the way the author avoids direct reference to a viewer in her poem, not even an adjective (shiramu, “whitening,” for instance, being presented in verbal form) to represent an emotional response. She also uses no metaphor, no allusion, not even a semantic proposition. Instead, she offers us a scene “as it is” (ari no mama), without explicit mediations: the moment of change when the moon is reduced to a pale sphere as the sun rises.

Sakuheimon’in’s poem recalls another from her father’s personal collection, Fushimiin gyoshū (The collection of Retired Emperor Fushimi, mid-fourteenth century; no. 1557), although we do not know which came first.

|

The color of frost |

niwa no omo wa |

|

begins whitening the ground |

shimo no iro yori |

|

of my garden court; |

shiramisomete |

|

and fading, paler all the while— |

usuku kieyuku |

|

the moon lingering at dawn. |

ariake no kage |

Fushimi’s poem is like his daughter’s in offering no subjective reference to a speaker, no adjectives, only a scene presented “objectively.” Kyōgoku Tamekane (1254–1332), a grandson of Tamie’s who was the chief theorist of the school, tells us that such an approach is not intended as a version of pastoral but rather an attempt to “become one” with the scene in Buddhist terms, thus capturing the truth of it, in its moment (orifushi no makoto). From this we can assume that neither author was intent on rendering a scene from experience—however much experience may have conditioned the process—so much as on presenting an allegory of harmonious union. Sakuheimon’in’s poem, in particular, might be described as a meditation on the transformative effects of light. Lacking even the garden of Fushimi’s poem, her scene has no immediately human or even earthly reference points, only the expanse of the broad sky high above us as it passes through a process of illumination in which the moon, a brilliant orb in the darkness, is absorbed into gathering sunlight.

KYŌGOKU TAMEKO 京極為子, Gyokuyōshū 1535 (Love): “Written as a love poem”

|

In sad reverie |

mono omoeba |

|

I abandon my writing brush |

hakanaki fude no |

|

to its own vain whims— |

susabi ni mo |

|

and find that what I write down |

kokoro ni nitaru |

|

is like what is in my heart. |

koto zo kakaruru |

CONTEXT: Kyōgoku Tameko (d. 1316?) was a lady in service to Empress Eifuku (1271–1343), consort of Emperor Fushimi. Along with her brother, Tamekane, she was an artistic leader of the Kyōgoku school. The headnote to this poem tells us nothing of the circumstances behind its composition but gives us a crucial prompt: the dai of love. Without that context, we might wonder about the cause of the “sad reverie” of the first line. Thinking about the past? Worldly affairs? Illness? Tameko, or perhaps a later editor, decided to resolve the issue, by implicitly acknowledging the ambiguity: “Written as a love poem.”

COMMENT: While mainstream love poems tend to employ striking imagery and complex rhetoric, the Kyōgoku school poets with whom Tameko was associated sought to represent the various emotions of love—yearning, anticipation, rejection, resentment, and so on—with fewer verbal mediations, emotions “just as they are” (ari no mama). Thus Tameko does not use a natural image to express her mood but something in her immediate surroundings: a writing brush. We see before us a lady sitting by her desk, musing about her relationship with some unidentified man, taking out an inkstone and brush and jotting down something—probably old poems—just to pass the time. Calligraphy practice was a constant in aristocratic life, where the need to write notes and letters was a daily thing. Here, however, the speaker picks up her brush in a moment of boredom, with no particular reason, and finds that her hands and heart are connected. Ironically, we encounter a distracted mind refusing to be distracted.

Although Tameko’s poem stands on its own and needs little in the way of explication, knowing that she alludes to a scene from The Tale of Genji enriches our understanding—which was the primary and immediate purpose of allusion in traditional court poetics. The scene is from the “Wakana” (Spring shoots) chapter and describes how Murasaki, Genji’s companion of many years, turns to brush and ink for distraction when she is feeling vulnerable after Genji has just married the Third Princess. “Setting herself to writing practice, she would find that, quite spontaneously, the old poems flowing from her brush would reveal her worries of the moment, impressing upon her how heavily those things weighed on her mind” (4:81).

The general custom in waka poetry was to allude to prose passages rather than poems in The Tale of Genji, and in that sense Tameko is following the canons of her day. Yet the passage she chose was not a particularly famous one, which leaves one impressed with how thoroughly she knew the tale.

TONNA 頓阿, Tonna hōshi ei 42 (Spring): “At day’s end, after viewing blossoms”

|

Till evening comes … |

kurenaba to |

|

so I thought as I spent the day |

omoishi hana no |

|

beneath the blossoms. |

ko no moto ni |

|

But how hard it is to abandon |

kikisutegataki |

|

the sound of the vespers bells! |

kane no oto kana |

CONTEXT: Tonna was a man of samurai birth who took the tonsure early to dedicate himself to poetry as a religious Way, living in various cottages in Kyoto, where he carried on a thriving literary practice involving textual work, teaching, and of course poetry gatherings. “Composing on topics” (daiei) was central to medieval poetic culture. Poem contests were still held, and hyakushu-uta (sequences of one hundred poems) were still commissioned for poetry gatherings. But even in casual gatherings after such events people often composed extemporaneously (tōza) on dai chosen by lots, a practice that allowed professional poets like the monk Tonna to show their mettle, as he does in this poem from Tonna hōshi ei (Poems by the lay monk Tonna, no. 1357).

COMMENT: Fujiwara no Tameie wrote in Eiga no ittei (The foremost style of poetic composition, early 1170s, p. 202) that the challenge of daiei was to abide by precedent while adding “something a little different” when occasion allowed. Since “at day’s end, after viewing blossoms” demanded treatment of cherry blossoms—the most timeworn dai of the entire classical canon—Tonna would have taken it as a special challenge. His speaker begins by presenting himself as waiting but then gives us a sound from day’s end, the vespers bells that rang throughout Kyoto at the end of each day. In so doing he focuses on the poetic “essence” of his dai, based on precedent and informed imagination, what critics called hon’i. Almost certainly he had in mind a poem (Shin kokinshū, no. 116) by Nōin (988–1050?):

“Written when he was in a mountain village”

|

To a mountain village |

yamazato no |

|

at evening on a spring day |

haru no yūgure |

|

I came, and saw this: |

kite mireba |

|

blossoms scattering on echoes |

iriai no kane ni |

|

from the vespers bells. |

hana zo chirikeru |

For Nōin and Tonna, both monks, the temple bell symbolized Buddha’s voice calling people away from worldly cares. In Nōin’s case the sound transforms the falling blossoms into an allegory of transient beauty in a world of universal decline and death. Tonna, on the other hand, focuses our attention on the irony of how the sight of the blossoms is replaced by the sound of the bell, how one sensory delight follows another, both teaching the same message. At first, the speaker plans to stay only till dusk, thinking there would be no reason to tarry. But the sound of bells reminds him of Nōin’s poem and awakens him to another subtle beauty that only gains in attraction as daylight fades and the blossoms literally recede from view.

PRINCE MUNENAGA 宗良親王, Rikashū 366 (Autumn): “Written when he was looking at autumn leaves, at a time when he was living in a mountain village”

|

These showers falling |

kokorozashi |

|

on a path back in the mountains |

fukaki yamaji no |

|

must have a kind heart— |

shigure kana |

|

dyeing leaves in autumn hues |

somuru momiji mo |

|

that only I shall see. |

ware nomi zo miru |

CONTEXT: Munenaga Shinnō (1311–1385?) wrote this poem when he was living away from Kyoto, embroiled in the political conflicts during a period of divided rule between the Northern Court in Kyoto and the Southern Court in the provinces. From 1337 on, he lived mostly in remote places like Yoshino, Shinano, and Echigo, finally passing away, sometime before 1389, in the provinces, far from Kyoto.

COMMENT: The majority of poems written from the Shin kokin age onward into the Edo period are on dai, and records show that this was true of Munenaga’s poems as well. And even when he writes about what is before his eyes, he employs mostly traditional images and ideas and creates a model of ushin, or “refined feeling.” Yet headnotes do reveal deeply personal dimensions to some of Munenaga’s poems. The rain showers in the poem here seem to offer consolation as they do the work of dyeing leaves. Normally, however, a poet would look forward to sharing such beauties with friends in the capital. If there is comfort in the constancy of natural processes, then, there is also a sense of alienation. And somehow the poem gains power because we know that Munenaga is not just creating a poetic conception—which it would be easy to do, adopting the voice of a recluse, for instance—but is actually looking out on a scene that must indeed have felt lonely. While he does not allow the realities of politics to invade his poem, he must have known that readers would know his situation. The final “that only I shall see” is, we know, more than rhetorical posturing for an audience, as is also the case with poems like the following lament, also from his personal anthology, Rikashū (Collection of the lord of the Bureau of Ceremonies, ca. 1374; no. 790): “Perhaps because I went to sleep with things on my mind, in my dreams I seemed to see only things of the past. After rising the next morning I wrote this”:

|

Sleep leads to dreams; |

nureba yume |

|

and waking, to reality. |

samureba utsutsu |

|

One way, or another, |

to ni kaku ni |

|

I never forget the past— |

mukashi wasururu |

|

not for an instant of time. |

toki no ma mo nashi |

A poem in the category of “Reminiscence,” perhaps? For Munenaga, living in his hut in the mountains, a happier youth and intervening trials must have been impossible to forget.

SHŌTETSU 正徹, Sōkonshū 7061: “Lightning on a dark night”

|

Even in its glow |

terashite mo |

|

my heart remains as ever, |

kokoro wa yami no |

|

still in the gloom; |

mama nareba |

|

it’s for someone besides me— |

waga mi no yoso no |

|

this lightning in the night. |

sayo no inazuma |

CONTEXT: Shōtetsu was born into a samurai family but entered a Buddhist temple as a young man and dedicated himself to poetry as a Buddhist Way. He attracted numerous disciples, including men later known primarily as renga poets, including Shinkei. He also had many elite patrons, such as the samurai of the Hatakeyama clan at whose monthly gathering (tsukinamikai) he composed the poem here.

COMMENT: Buddhism was a category in the court tradition, but Buddhist ideas and ideals appear in poems written on more secular themes as well. The first thing we notice about this poem by a Zen monk is how skillfully it is structured, with the two elements of the dai (“gloom” and “lightning”) separated as convention required and with the initial “glow” (the verb terasu, the first word in the Japanese) reaching forward to “lightning” (inazuma, last word in the Japanese) at the end. Between those poles, we confront a man in the dark. Assuming that Shōtetsu speaks for himself may go too far; the poem was on a dai that, if we take its essence to be the brevity of lightning as a natural phenomenon, the poet articulates skillfully.

In Buddhist thought the world is dark by definition, and strict Zen practitioners did not believe in saviors such as Amida. For Zen monks the goal was a moment of enlightenment that—usually after devotion and labor—might come in a flash. Yet the burden of the poem is that if enlightenment has come for somebody, it must be for someone else (yoso). Ironically, this makes more intense the gloom (yami) that remains. A similar idea comes through in another poem on “lightning,” also from Shōtetsu’s personal anthology, Sokonshū (Grassroots collection, precise date unknown; no. 10959):

|

In the dark of night, |

kuraki yo no |

|

to whom shall I pour out |

tare ni kokoro o |

|

what is in my heart? |

amasuran |

|

Suddenly the clouds blink— |

kumo zo matataku |

|

a flash of autumn lightning. |

aki no inazuma |

The Buddhist “prompts” of the first poem—glow (terasu) and gloom (yami)—are absent in this case, but the existential loneliness (sabi) remains; and the phrase “to whom shall I pour out / what is in my heart” expresses even more effectively a longing for something warmer than enlightenment—human companionship. The use of the word “blink” (matataku), an unusual metaphor, with its human connotations, stresses the point even more starkly. Whatever “eye” the lightning throws on the speaker’s very human situation seems a cold one indeed.

INAWASHIRO KENZAI 猪苗代兼載, Sōgi shūenki (pp. 459–60)

|

Dew on the branch tips, |

sue no tsuyu |

|

raindrops beneath the trees— |

moto no shizuku no |

|

these are but tokens |

kotowari wa |

|

of the order of our world, |

ōkata no yo no |

|

shared by one and all. |

tameshi nite |

|

Yet when it is a close friend |

chikaki wakare no |

|

one is parting from, |

kanashibi wa |

|

somehow the sorrow you feel |

mi ni kagiru ka to |

|

seems for you alone. |

omōyuru |

|

Ah, since we met long ago, |

nareshi hajime no |

|

how much time has passed, |

toshitsuki wa |

|

months adding up to make years |

misoji amari ni |

|

more than thirty times. |

nariniken |

|

In those days far in the past, |

sono inishie no |

|

so kind was he |

kokorozashi |

|

that now nothing would I grudge |

ōharayama ni |

|

to express my thanks— |

yaku sumi no |

|

not even my life itself, |

keburi ni soite |

|

which I would gladly give |

noboru to mo |

|

to rise with smoke from charcoal, |

oshimarenu beki |

|

sent from Ōhara. |

inochi ka wa |

|

We were in the East Country, |

onaji azuma no |

|

each on his journey, |

tabinagara |

|

but separated so far |

sakai haruka ni |

|

that the wind took far too long |

hedatsureba |

|

to bring me tidings. |

tayori no kaze mo |

|

Rising from sleep |

ari ari to |

|

on my pillow of boxwood, |

tsuge no makura no |

|

I was in a dream |

yoru no yume |

|

and unable to waken. |

odorokiaezu |

|

Still, though, I set off, |

omoitachi |

|

toiling over field and hill, |

noyama o shinogi |

|

hoping as I went |

tsuyu kieshi |

|

to witness his form, at least, |

ato o dani tote |

|

after his passing— |

tazunetsutsu |

|

while the mountains on the way |

koto tou yama wa |

|

showed no hint of care, |

matsukaze no |

|

replying to my queries |

kotae bakari zo |

|

with only the wind in the pines. |

kai nakarikeru |

Envoy

|

What foolishness |

okururu to |

|

to berate being left behind! |

nageku mo hakana |

|

How long will I last, |

iku yo shi mo |

|

my body a mere dewdrop |

arashi no ato no |

|

left in the wake of a storm? |

tsuyu no ukimi o |

CONTEXT: Inawashiro Kenzai (1452–1510) was a renga master from Aizu who studied and practiced in Kyoto for some years before retiring to the East Country. His chōka memorializes one of his teachers, Sōgi (1421–1502), who died at Yumoto on the eastern side of the Hakone Mountain range without Kenzai’s being able to pay his last respects. Sōchō (1448–1532) appended Kenzai’s poem to his own account of the master’s death, Sōgi shūenki (A record of Sōgi’s passing, 1502).

COMMENT: In the medieval period chōka were often used for laments. Kenzai’s poem includes one kakekotoba (tsuge, meaning both “inform” and “boxwood”), but it is one of Kokinshū vintage, and he does not employ other Man’yōshū conventions, using neither parallelism nor makurakotoba, instead using the medieval technique of honkadori. His first reference, given almost verbatim, is to Shin kokinshū no. 757, a didactic poem by Archbishop Henjō (816–890), to which Kenzai provides an emotional response.

|

Dew on the branch tips, |

sue no tsuyu |

|

raindrops beneath the trees: |

moto no shizuku ya |

|

these are but tokens |

yo no naka no |

|

of how in this world we mourn |

okure sakidatsu |

|

as others go—or go ourselves. |

tameshi naruran |

A second allusion is to an anonymous poem (no. 1208) from Goshūishū sent to someone who asked the author “if he would like a gift of charcoal”:

|

Were you so kind |

kokorozashi |

|

as to pledge me charcoal |

ōharayama no |

|

from Mount Ōhara |

sumi naraba |

|

then I would put that warmth to use |

omoi o soete |

|

in lighting the coals on fire. |

okosu bakari zo |

So playful a poem may seem inappropriate in the context of a lament, but Kenzai sidesteps the humor, alluding only to the “kindness” shown by Sōgi as a teacher (“as great as Mount Ōhara”) in order to express his own gratitude. Mount Ōhara was another name for Oshioyama, located west of Kyoto and known for its charcoal kilns.

Kenzai’s poem contains no vestige of a public voice, describing a personal grief so intense that even the natural landscape offers no relief. While it does contain a narrative element, then, its “story” focuses less on outside events than on the very medieval themes of transience and Buddhist resignation.

SASSA NARIMASA 佐々成政, Taikōki (p. 28)

|

In the world of men, |

nanigoto mo |

|

everything has changed— |

kawarihatetaru |

|

and changed utterly. |

yo no naka o |

|

And yet, all unknowing, |

shirade ya yuki no |

|

white snow keeps falling down. |

shiroku fururamu |