Late eighteenth-century painting by Matsumura Gekkei of a haikai master and students, from Shin hanatsumi by Yosa Buson.

Courtesy L. Tom Perry Special Collection, HBLL, Brigham Young University.

MATSUE SHIGEYORI 松江重頼, Enokoshū 1451 (Winter)

|

Falling snow |

furu yuki wa |

|

puts makeup on the City: |

kyōoshiroi to |

|

a Kyoto belle. |

miyako kana |

CONTEXT: Matsue Shigeyori (1602–1680) was born in Matsue but spent his adult life in Kyoto as a wealthy merchant. He studied renga in his younger years but gained his reputation in haikai. Shigeyori’s poem shows that already in the early 1600s Kyoto geisha were known for their distinctive white makeup. Although pre-Edo sources contain references to dancers and “pleasure women” who in some ways prefigure the geisha, it was later, in Shigeyori’s own time, that licensed entertainment districts were established in cities like Edo and Kyoto; and it was then that the term began to take on its conventional meaning.

COMMENT: What qualifies this hokku as haikai—i.e., humorous or unconventional verse? Certainly not the first line—literally, “the snow falling down.” So much was “snow” the quintessential kigo (season word) of winter that according to the rules of classical linked verse it could appear no more than four times in a sequence, unless it was used only figuratively, as in phrases like hana no yuki, “a snowfall of cherry blossoms.” In Shigeyori’s verse, the snow is real, but he immediately stamps his work as a haikai effort by a metaphor that would not appear in traditional forms: shiroi, or “makeup,” specifically the thick white facial makeup worn by geisha. Even in Edo times, some courtiers still wore facial powder, but Shigeyori no doubt refers to women he knew from his own experience of Kyoto culture, gesturing toward a whole world of pastimes and pleasures considered too risqué for traditional genres.

After the establishment of the shogun’s government there in 1600, Edo gradually overtook Kyoto as the most important of Japanese cities. Yet many warlords continued to maintain large city estates there, and the many temples and shrines in the city and its environs made it an important site of worship and pilgrimage, as well as tourism. The process of change was thus gradual, and when Enokoshū (Mongrel-puppy collection), a large collection of haikai from the pre-Bashō era, was published in 1633, Kyoto was still a grand metropolis, known as Miyako, “the capital” (translated here as “the City”), and it was still the preeminent Japanese city of the time. Rather than toward the imperial palace, however, Shigeyori’s metaphor gestures toward the merchant and pleasure districts of the city, which were full of inns, teahouses, shops, theaters, and precincts of worldly pleasures. The snow of his first line thus suggests a broad view of the city, appearing pure and white, showing an idealistic scene of the sort described by the poet Murata Harumi (1746–1812), who wrote that under snow “shop streets, too, take on a sudden sheen, reminding one of life in a mountain village and making even the hats and cloaks of tradesmen seem somehow things of beauty” (Kotojirishū, p. 609). Shigeyori’s mention of the makeup of a geisha, on the other hand, cannot but make us think of another sort of beauty pulsing beneath the makeup, both the makeup of the woman and that of the lively city that she represents.

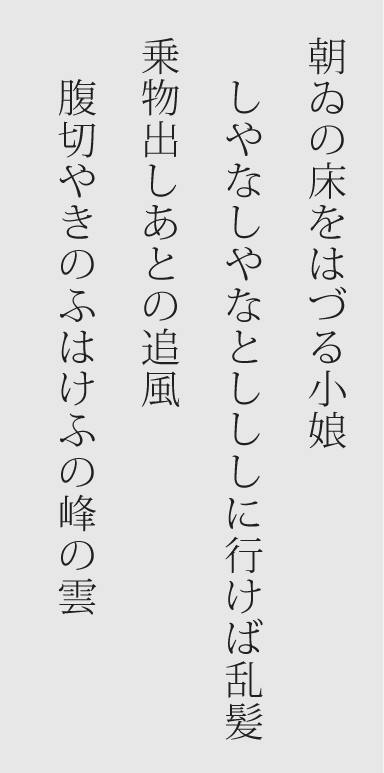

OZAWA BOKUSEKI 小沢卜尺 and OTHERS, Danrin toppyakuin 882–85: From the eighth of ten hundred-poem sequences composed in the summer of 1675

|

82 |

In bed at morning |

asai no toko o |

|

the girl acts shy. |

hazuru komusume |

|

|

Bokuseki |

||

|

83 |

In fine form |

shana shana to |

|

she goes off to pee— |

shishi shi ni yukeba |

|

|

hair in tangles. |

midaregami |

|

|

Shōkyū |

||

|

84 |

As the cart leaves, |

norimono ideshi |

|

wind follows behind. |

ato no oikaze |

|

|

Itchō |

||

|

85 |

Harakiri! |

harakiri ya |

|

Yesterday, today, |

kinō wa kyō no |

|

|

peaks of cloud. |

mine no kumo |

|

|

Zaishiki |

||

CONTEXT: Ozawa Bokuseki (d. 1695), Deki Shōkyū, Toyoshima Itchō, and Noguchi Zaishiki (d. 1719) were all haikai devotees living in Edo. The Ten Hundred-Verse Sequences of the Danrin School (Danrin toppyakuin) were composed in 1675 and published that same year.

COMMENT: The rules of haikai-style linked verse allow for more rapid changes than in classical renga, as reflected in these verses by Edo poets, some of them disciples of Nishiyama Sōin (1605–1682), who was himself a transitional figure between classical linked verse and haikai and leader of a faction referred to as the Danrin school—literally, “a grove for chatting”—dedicated to an informal style. The first verse presents an inexperienced young woman lingering in bed, perhaps after a night of lovemaking. Shōkyū’s tsukeku expands that scene, showing a girl trying to act with nonchalant elegance that only draws attention to the fact that she is going to relieve her bladder. Itchō’s verse, however, employs no vocabulary that would indicate love as a category: it is only when joined to the previous verse that we see the man in the cart leaving after a night with a woman. Then Zaishiki’s verse pivots to another topic altogether, mujō, or “transience.” Now the girl is forgotten as the cart is recast as a conveyance for the body of a high-ranking man going off to a cremation site, the trailing wind being transformed into the idea of samurai who will be obliged to follow him in death by committing ritual suicide. (The latter is suggested by the word oibara, a compound formed by the oi of oikaze in verse 84 and the hara of harakiri in verse no. 85). Thus we move from a shy girl to harakiri, all in just four verses, although old associations (“hair” relating back to “girl,” “follow” back to “goes,” “cloud” back to “wind”) still figure in the linking.

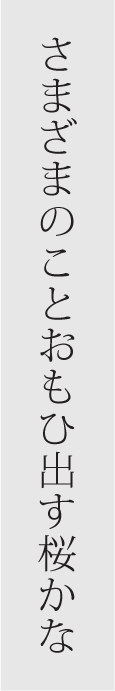

MATSUO BASHŌ 松尾芭蕉, Oi no kobumi (p. 318)

|

Ah, the jumble of things |

samazama no |

|

they call back to mind— |

koto omoidasu |

|

cherry blossoms. |

sakura kana |

CONTEXT: Matsuo Bashō was a man of modest background who in his midtwenties became a professional haikai poet. He lived in Edo but traveled widely and left travel records, as well as hokku, linked-verse sequences, and pieces of haikai prose. Bashō wrote this hokku in his hometown of Iga Ueno in the Second Month of 1688, when he was viewing the blossoms at the villa of Tanganshi, while on the journey later recorded in Oi no kobumi (Knapsack notes, 1688). Tanganshi was the son of Tōdō Sengin, the samurai patron of Bashō’s youth, whose death in 1666 had precipitated a crisis in Bashō’s life that we believe led him to pursue haikai as a profession. The setting, already nostalgic because of memories of his deceased parents, was doubly so because of memories of the same garden more than two decades before. The cottage where Bashō composed the hokku was thereafter known as Samazama-an, incorporating the first line of the poem.

COMMENT: In Haikai sabi shiori (Sabi and shiori in haikai, 1812, p. 385), Kaya Shirao (1738–1791) quotes a remark by his teacher, Shirai Chōsui (1701–1769), that sees an allusion to the “Suma” chapter of Genji monogatari, when Genji was in exile. “In Suma, the New Year came, and as the days grew longer, time was heavy on his hands. As the young cherry trees he had planted began to bloom, a few of their blossoms floated on the wind in mild skies, and so many things were called to mind that he was frequently in tears” (2:204).

The technique of allusive variation is not employed in haikai as often as it is in waka, perhaps because so short a form cannot accommodate a long passage of text. Still, allusions do appear. In this case, Bashō does what ancient poets were counseled to do: to put an old idea in a fresh context. In the tale, the eponymous character gazes out on cherry trees transplanted into his garden just the year before, while Bashō looks at cherry trees from long ago. But the phrase yorozu no koto oboshiiderarete (similar to samazama no koto omoidasu in Bashō’s poem) is vague enough that it could refer as much to Genji’s whole life as to his life at Suma. The important thing for Bashō is the idea of blossoms—a yearly marker of passing time—evoking memories for him, as for Genji. Writing about cherry blossoms was a challenge. Bashō’s accomplishment is in the way he makes the prominence of cherry blossoms in poetic culture the explicit theme of the poem. What he gives us is not natural description but one man’s reaction to a natural scene, one of the hallmarks of Bashō’s style. What is he remembering? No doubt his own youth and his patron, Sengin, first of all; but hovering in the background are cherry blossoms in thousands of other poems brought “again to mind.”

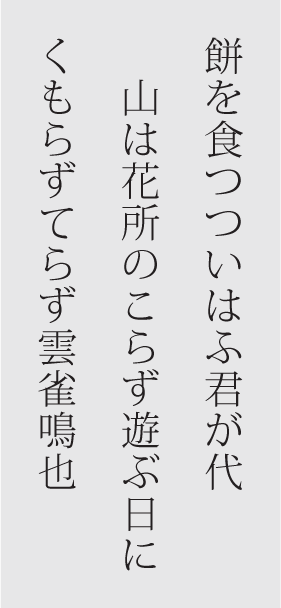

YAMAMOTO KAKEI 山本荷兮, Haru no hi 292–94

|

34 |

Gobbling up rice cakes, |

mochi o kuraitsutsu |

|

he celebrates the Reign |

iwau kimi ga yo |

|

|

Tankō |

||

|

35 |

Mountains in bloom: |

yama wa hana |

|

everyone, everywhere |

tokoro nokorazu |

|

|

on holiday. |

asobu hi ni |

|

|

Tōbun |

||

|

36 |

Not cloudy, not sunny— |

kumorazu terazu |

|

and a lark in song. |

hibari naku nari |

|

|

Kakei |

||

CONTEXT: Yamamoto Kakei (d. 1716) was a samurai and Sugita Tankō, a confectioner; Tōbun’s occupation is unknown. All were Nagoya disciples of Bashō. Kakei was the most prominent, a member of the Teitoku school who later became a disciple of Bashō’s and, from the mid-1690s onward, forsook haikai for renga. The links here ended a thirty-six-verse sequence in Haru no hi (Spring day, 1686) composed by six men of the Nagoya area, who began their effort at the country cottage of Sugita Tankō, one of the participants, but completed it in the rooms of Yamamoto Kakei, the next day, on the nineteenth day of the Third Month of 1686. Custom dictated that the final verse (no. 36, called the ageku) of a haikai sequence be in the spring category and that it be propitious in tone. Kakei’s ageku fulfills both requirements.

COMMENT: One of the dynamics at work in renku sequences is between nature and human affairs. (Sometimes the two are referred to as tenchi ninjō.) The three verses show that dynamic at work. Tankō creates the amusing scene of someone unceremoniously chomping on rice cakes in honor of the New Year. Rather than adding to that scene visually, Tōbun evokes a similar situation a few months later, as people take the day off to enjoy mountain cherry blossoms—an example of linking by hibiki, or “reverberation,” with “holiday” serving as an echo of “celebrate.” The final verse, by Kakei, however, shows no human involvement at all, instead focusing on the serene, gentle call of a lark in hazy spring skies. In this sense, the last link is a keikizuke, or “scenery link,” a term that means the same thing it does in renga discourse—that is, a natural scene with affective overtones. As a final verse, the singing draws our attention upward in search of the larks, who are traditionally figured as flying so high that they cannot be detected by the human eye. Thus we end the sequence with a kind of benediction, the religious connotations of that word not being inappropriate since the successful completion of a sequence was considered a votive act supplicating for peace and order in the world.

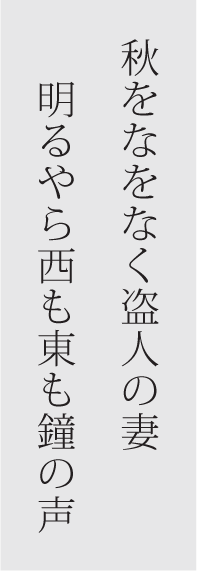

OKADA YASUI 岡田野水, Arano 1110 (Miscellaneous)

|

In autumn, more tears |

aki o nao naku |

|

for a sneak thief’s wife. |

nusubito no tsuma |

|

Must be daybreak. |

akuru yara |

|

From west, from east, |

nishi mo higashi mo |

|

bells sounding. |

kane no koe |

|

Yasui |

|

CONTEXT: Okada Yasui (1658–1743) and Ochi Etsujin (b. 1656) were Nagoya merchants. Prominent disciples of Bashō, they in turn practiced as haikai masters in their local area. The impetus behind the sequence (from Arano, Withered fields, 1689) involved here was a message in the Fourth Month from one Yamaguchi Sodō (1642–1716), who was then living near Mount Hiei, near Kyoto. Letter writing was an art form for literati but also a practical necessity, as all correspondence was undertaken by hand. Runners carrying mail were what kept shopkeepers and innkeepers along thoroughfares in business. As was typical, Sodō wrote a highly literary note, appending a hokku that was used to begin a sequence.

COMMENT: Etsujin presents us with the domestic scene of a wife whose tears increase with the coming of autumn—but with a twist, for her husband is a thief. Thieves appear sometimes in waka, but only sublimated through the image of shiranami, “white waves” or “breakers,” and they figure in serious renga only rarely. But in haikai they are fairly common, probably because they were such a part of the cast of characters in everyday life. But rather than focusing on the thief himself, Etsujin cagily focuses on the man’s wife, reminding us that even thieves have families with their own routines. The punishments for thievery were severe and could involve a culprit’s dependents.

Yasui’s response to Etsujin’s brief sketch offers a scene of bells ringing at daybreak that will make moving in a new direction easier for the next participant—what the commentaries call a yariku. But in the context of the link, the verse is a variation on the old trope of being kept awake by worries on an autumn night. The first line is thus interior monologue in a highly colloquial idiom: “Must be daybreak, I s’pose.” Then comes the explanation for the riddle of the woman’s tears: the bells, their warning echoes impinging from all sides. Thus Yasui fills in one of the elliptical corners of the maeku. In classical poems, such sounds evoked images of temples and often signaled lovers’ farewells or suggested scenes of religious life. In Yasui’s link, however, the bells inspire worries of a more worldly sort, and the tears are not shed in a romantic or devotional setting. Summer was the best season for thieves, since people were often out late carousing; autumn, always figured as melancholy in poetry, was a more dangerous time as well. Hence the heightened sense of worry. “Why isn’t he back yet?” “Has he been injured?” “Or, worse yet, caught?” Finding sympathy for the thief himself may be difficult, but we readily feel sorry for the wife who waits for his return every time he is “at work.”

SUGIYAMA SANPŪ 杉山杉風 and OTHERS, Hatsukaishi hyōchū 21–23

|

Since first bloom |

saku hi yori |

|

|

he’s been counting carts— |

kuruma kazoyuru |

|

|

beneath the blossoms. |

hana no kage |

|

|

Sanpū |

||

|

22 |

On the bridge, light rain, |

hashi wa kosame o |

|

shimmering like heat. |

moyuru kagerō |

|

|

23 |

Leftover snow, |

nokoru yuki |

|

leftover scarecrow: |

nokoru kagashi no |

|

|

uncommon sights. |

mezurashiku |

|

|

Shugen |

||

CONTEXT: Sugiyama Sanpū (1647–1732) was one of Bashō’s disciples, as were Senka and Shugen, about whom little else is known. Bashō left few critical writings, but in 1686 he penned a commentary on some of the verses from a sequence involving himself and some of his disciples titled Hatsukaishi hyōchū (Comments on the first sequence of the New Year) from which the verses here are taken.

COMMENT: Scholars see Bashō’s comments as early articulations of his aesthetic of karumi, or “lightness,” a term he uses in his characterization of verse 22: “Notice his way of handling the season, lightly and casually [karoku yasuraka ni]. What one should do in linking to a blossom verse is to do so straightforwardly, lightly [yasuyasu to karoku].” Thus he praises Senka for favoring delicacy over drama. About Shugen’s verse Bashō says more: “Again, a spring scene. Restrained linking technique. The worn-out scarecrow standing there, retaining the scent of the fields and rice paddies and orchards, makes for a most touching scene. I call it highly affecting the way autumn and winter remain on into spring, under a light layer of snow” (p. 471).

Here, the terms “a touching scene” (aware naru keiki) and “highly affecting” (kansei nari) derive from courtly poetics. Elsewhere in the same comments Bashō uses the terms yūgen, taketakashi, ari no mama, yojō, and omoshiroshi, signaling conscious engagement with courtly traditions. This should be no surprise: among Bashō’s stated ambitions was reconnection with the past in spirit, distancing himself from what he attacked as trivial in the haikai poetry of more recent times. In this sense, he reversed the medieval dictum of “old words, new heart” (Eiga taigai, p. 188), seeking to articulate the high ideals of the past with contemporary vocabulary and subject matter.

MUKAI KYORAI 向井去来, Kyoraishō (p. 445)

|

Nightclothes of fine twill, |

aya no nemaki ni |

|

reflecting sunlight. |

utsuru hi no kage |

|

In tears, she looks |

naku naku mo |

|

for little straw sandals— |

chiisaki waraji |

|

with no success. |

motomekane |

CONTEXT: Mukai Kyorai (1651–1704) was a student of Bashō’s who after the latter’s death was the leader of the Bashō school in the Kansai area. Records tell us that this link was composed for a thirty-six-verse sequence held at the cottage of the head priest of Kamigoryō Shrine in Kyoto late in 1690. Nine people participated, all disciples or associates of Bashō’s. Among them was Sakanoue Kōshun (d. 1701), a disciple of Kitamura Kigin’s (1624–1705), one of Bashō’s own teachers in his early days as a haikai poet. He is probably the source of the following anecdote also recorded in Kyoraishō (Kyorai’s notes, 1702–1704, p. 445):

When this maeku was produced in a gathering, the assembled people were having trouble coming up with a link. The master said, “This verse—it shows a high-ranking woman traveling, I think,” and someone came up with a link right away.

Kōshun said, “No sooner did he say it was a high-class woman than someone came up with a tsukeku. The way Bashō’s disciples got training was something special.”

COMMENT: People in the za had to produce verses on the spot, usually within a few minutes. For them techniques were thus not just aesthetic in purpose but also practical aids to composition. In the case of this tsukeku, we have an anecdote that illustrates how the idea of kuraizuke (linking by social station) assisted in responding to a difficult verse.

The challenge of the maeku, composed by a man named Oguri Shiyū (d. 1705), was that it was vague as to any surrounding context, such as who the owner of the “nightclothes of fine twill” was. When no one managed to come up with anything, Bashō offered a hint to set the other participants off in a useful direction by providing an imagined social station and purpose for the owner of the fine nightclothes—a person of substance, on the road, probably staying at an inn. Kyorai then did the rest, coming up with a credible human scene: a rich woman, probably young and perhaps not used to being on the road, still in her nightclothes (or is she perhaps taking them off to get dressed in her traveling clothes?), searching in frustration for her little straw sandals. Thus a maeku that offers no more than the single image of twill sparkling in morning sunlight is brought to life, and all thanks to a simple suggestion by the master about kurai. The “little” straw sandals is a master stroke, stopping short of saying “pretty” but suggesting the same, while also hinting at youth and inexperience. By the word “high-ranking woman” (jōrō), Bashō probably meant to suggest a young married woman. Kyorai’s verse gives no pronoun at all, however, leaving leeway for the next person in the linking process.

NAITŌ JŌSŌ 内藤丈草, Haikai Shirao yawa (p. 197)

|

Ōhara Moor. |

Ōhara ya |

|

Butterflies out dancing |

chō no detemau |

|

in misty moonlight. |

oborozuki |

CONTEXT: Haikai Shirao yawa (Shirao’s night tales about haikai, 1833), a collection of anecdotes, offers a story about the creation of this hokku:

This is a verse by Jōsō. When Bashō first heard it, he asked, “I wonder, these butterflies dancing—what would they look like?”

Jōsō replied, “Last night I actually walked through Ōhara and saw them at it.”

“Well, in that case, the verse is superb,” Bashō said, “truly, this is Ōhara,” and was extravagant in his praise, so it is said.

Naitō Jōsō (1662–1704), a samurai who took the tonsure at a young age to live as a literatus, was among Bashō’s chief disciples. Ōhara Moor, just north of Kyoto, was associated with a number of poignant events, especially Lady Kenreimon’in’s entry into a hillside temple there after the fall of the Heike clan in the late 1100s. Bashō praised Jōsō’s dreamy scene for capturing the essence of the place.

COMMENT: The provenance established by the anecdote in this case states an important principle that goes back at least as far as Fujiwara no Tameie, who in one of his treatises says that there was a special place in practice for poems composed “in accord with actual scenery” (Eiga no ittei, pp. 201–2). The nature of Bashō’s doubts is not clear (Is he doubting that butterflies actually dance? That they come out at night? Or were they perchance moths rather than butterflies?), but he ends up praising the poem in any case.

Without corroboration, determining whether a verse was based on actual observation is difficult, but an early anthology (Arano, 1689) offers poems such as these (nos. 447, 570, 654) by obscure disciples of Bashō’s that are easy to imagine as “real.”

|

Snow starts to fall |

yuki furite |

|

and into the horse stable |

umaya ni hairu |

|

go the sparrows. |

suzume kana |

|

In a big garden |

hironiwa ni |

|

he’s planted just one— |

hitomoto ueshi |

|

cherry tree. |

sakura kana |

|

Rainy evening: |

ame no kure |

|

mosquitoes buzzing around |

kasa no gururi ni |

|

my umbrella. |

naku ka kana |

|

Nisui |

|

UEJIMA ONITSURA 上島鬼貫, Onitsura haikai hyakusen (p. 211) (Autumn): “Strolling in the fields”

|

Autumn wind |

akikaze no |

|

blows in and passes by. |

fukiwatarikeri |

|

People’s faces. |

hito no kao |

CONTEXT: Uejima Onitsura (lay name Fujiwara Munechika, 1661–1738) was born to a sake brewer in Itami, Settsu Province. He studied medicine as a youth, and at eight years old he began his lifelong dedication to haikai. He studied under Nishiyama Sōin but remained an independent figure.

COMMENT: In time Onitsura became disillusioned with the wordplay of the Danrin style, instead arguing that the hallmark of good poetry was makoto, “sincerity,” a fundamental concept of Confucian dogma at the time that was also of some importance in court poetics. Like poets of the Kyōgoku faction in medieval times (who used that same term), Onitsura wanted objects to speak for themselves, revealing the rhythms of the phenomenal world. But the poem here shows that he was capable of complex conceptions. The first two lines present the most obvious quality of wind: that it blows by. But the word akikaze, “autumn wind,” of course communicates more than that. For one thing, the autumn wind is by definition a chilly wind, and one that we know blows leaves from the trees and contributes to the general trend toward decay that ends in winter. As a subtle way to tease out these qualities, the poet ends the poem with the evocative phrase hito no kao, “people’s faces.” Thus Onitsura uses the technique of apposition, leaving the task of overcoming the ellipsis to us as readers. The most likely scenario is that as they hear the wind blow by, people turn their faces up from whatever they are doing and notice the change in the landscape, thus coming together, in a way. And the reactions on those faces are various. Some enjoy the sight of things blown on the wind, others feel a sense of foreboding as winter comes on, still others may think about practical tasks that must be done—the possibilities are endless. Instead of the effect of wind on the leaves, then, we are left to imagine its effect on faces.

Onitsura also wrote highly colloquial poems such as the following (p. 220), on the topic “year’s end,” that invited criticism of the sort leveled at the waka poet Ozawa Roan.

|

You may resent it, |

oshimedomo |

|

but you’ll go to bed, get up— |

netara okitara |

|

to spring. |

haru de aro |

Some thought such poems went too far. The Zen priest Kyomyōshi Gitō (d. 1730), in a postface to Onitsura’s Hitorigoto (Talking to myself, 1718, p. 192), disagreed—“The diction of Onitsura’s haikai is not vulgar but simple and sincere [makoto]”—and compared him to the Chinese poetry of Tao Yuanming (365–427) and the Zen of Bodhidharma (fl. sixth century), founder of that sect.

NOZAWA BONCHŌ 野沢凡兆, Bashōmon kojin Shinseki (p. 264)

|

A cast-off skiff— |

sutebune no |

|

frozen, inside and out, |

uchisoto kōru |

|

on an inlet. |

irie kana |

|

Bonchō |

CONTEXT: Nozawa Bonchō (d. 1714), a Kyoto physician, was a sometime student of Bashō’s.

COMMENT: This haiku by Bonchō, recorded in a compendium of poems by Bashō’s disciples put together by Chōmu (1732–1795), calls to mind a waka by Shōtetsu on the topic “boat on an inlet”:

|

Owner unknown: |

nushi shiranu |

|

at evening, on an inlet, |

irie no yūbe |

|

with no one around— |

hito nakute |

|

just a rain cloak and a pole, |

mino to sao to no |

|

left behind in a boat. |

fune ni nokoreru |

As recorded by Tō no Tsuneyori (1401–1484) in Tōyashū kikigaki (Notes on conversations with Lord Tō, governor of Shimotsuke, 1456?, pp. 340–41), Shōtetsu’s poem (Sōkonshū, no. 5999) was attacked by the Nijō-school poet Gyōkō (1391–1455) as “the voice of a violent age,” in reference to the Mao preface to the Chinese Book of Songs. What offended was doubtless the starkness of the scene and the unsparing diction of the phrases nushi shiranu (owner unknown) and hito nakute (no one around). Shōtetsu paints an objective scene in the sabi mode: no metaphor, no figures of speech, nothing to signal a poem in the courtly tradition. Mainstream poems generally treat the subject of loneliness in more sentimental terms.

Whether Bonchō was thinking of Shōtetsu’s poem is not recorded, but we can be sure that Bonchō did not worry about such criticism. In haikai “common” objects and the less-elegant aspects of nature and human experience were not regarded as offensive. One thinks of a famous hokku by Bashō himself, written near the end of his life, in 1693, and recorded in Komo jishi shū (Straw-lion collection, 1693, p. 236):

“First day of the year”

|

Year in, year out, |

toshidoshi ya |

|

the monkey wears the mask |

saru ni kisetaru |

|

of a monkey’s face. |

saru no men |

While not objective in its rhetoric, this poem has none of the optimism one expects at the beginning of a new year. The idea of the monkey trapped forever, by decree of nature, behind a face that is comical to human eyes is boundlessly sad. And of course anyone—especially anyone getting on in years—looking at a monkey’s face is bound to notice its human qualities and realize that his predicament is not so far from our own. Basho’s reported comment on the verse was, “I was lamenting how people don’t make any progress but make the same mistakes year after year” (Sanzōshi [Three books], 1702, p. 566).

BONCHŌ AND BASHŌ, Kyoraishō (p. 434)

|

Lower Kyoto: |

shimogyō ya |

|

snow piles up, and then— |

yuki tsumu ue no |

|

night rain. |

yoru no ame |

CONTEXT: As noted, Nozawa Bonchō was one of Bashō’s disciples. An anecdote about the poem here recorded in Kyoraishō (pp. 434–35) tells us that Bonchō did not compose it alone.

At first, this poem had no first line. Beginning with the late master, everyone began suggesting lines, and finally this was the one decided upon. Bonchō, however, said, “Hmm,” and still wasn’t sure.

The late master said, “Try your own hand, Bonchō—suggest a line. If you come up with anything better, I won’t ever say another word about haikai.”

COMMENT: In this anecdote, revision is presented as a communal activity. Who contributed the first line is not entirely clear, but the story suggests it was Bashō himself. The anecdote has much to tell us about haikai culture. First, we see a poet with an incomplete poem, no doubt a common situation; many of Bashō’s own poems exist in many versions, some of them arrived at with input from other people. And as we think about poets trying to come up with a beginning line, we notice that Kyorai portrays a model for the master-disciple relationship in which the master prevails, but only after some give-and-take; authority is established through negotiation. And it is not by chance that Kyorai—author of the book in which it appears—is telling such a story as a disciple. The book was written after Bashō’s death and served as a claim to succession from the master.

But what is it about the version of the poem quoted by Kyorai that makes it superior? The answer has to do with the connotations associated with “lower” Kyoto, a place well known to the poets. Bonchō’s two lines present a natural scene of night rain falling onto accumulated snow but provide no specific setting—and no sense of human involvement or emotion. Establishing the scene as lower Kyoto, the commercial district of the city, always bustling with people, provides both those things, contributing a suggestion of liveliness to the scene and also making an implied contrast with the more upper-class upper section of the city. Thus as readers we imagine shopping districts, merchant tenements, streets and alleyways, rather than the spacious city estates of upper Kyoto, where at a little higher altitude snow might indeed still be falling. In this setting, we visualize slushy streets that add to the “lightness” (karumi) of the conception, while also injecting a sense of human involvement. Creating so concrete and evocative a context in just five syllables is no easy task, the anecdote implies. “A mountain village” would work, as would “a fishing village” or a time of day—“as evening descends.” But would any of those provide the same affective power and connotations beyond the words, moving beyond the aesthetic to the socio-aesthetic?

KAGAMI SHIKŌ 各務支考, Zoku Sarumino 3462 (Miscellaneous)

|

Sparrows sing |

jikidō ni |

|

by the monks’ dining hall. |

suzume naku nari |

|

Evening rain. |

yūshigure |

CONTEXT: Kagami Shikō (1665–1731) was born in Mino Province (modern Nagoya). He had firsthand experience of monastic life, having spent some years at Daichiji Temple in what is now Gifu, a Zen temple where his elder sister had had him placed as a young boy after the death of his father. Why he decided to leave the priesthood is not precisely known, but it seems likely that it was because of a desire to pursue further the more secular studies he undertook at the temple, which would have involved Chinese, along with some exposure to both Chinese and Japanese poetry. He studied in both Kyoto and Ise, at the same time beginning his activity in the world of haikai. He became a disciple of Bashō’s around 1690 when the master visited Mino on one of his journeys through the provinces. After Bashō’s death, he established a school of his own and was considered disloyal by some of Bashō’s other major disciples. The poem here is from the “Buddhism” chapter of Zoku sarumino (The monkey’s straw raincoat II, 1694), an anthology of poems by poets of Bashō’s school put together in the autumn of 1694, in Iga, just before Bashō’s death. Shikō assisted his master, but as it did not reach final form while Bashō was still living the anthology was viewed with some suspicion by many poets and scholars.

COMMENT: Although in the Buddhism category, Shikō’s poem presents a picture of everyday life rather than any doctrine, at least on the surface. Temples were places not just of study and meditation but also of labor of all sorts, especially for those of modest background in the lower ranks, as Shikō would certainly have been. For him, memories of daily life at Daichiji would have been of daily chores, and mealtimes would have been looked forward to as both respite from work and relief from pangs of hunger. Temple fare was notoriously bland, usually consisting of just vegetables and rice, meat being forbidden; but still one can imagine monks eager to receive their bowls. Rather than express this directly, however, Shikō takes an oblique approach, focusing on sparrows, and not inside the mess hall itself but outside. Buddhist doctrine taught that all beings shared in Buddha nature, though at different levels of grace, animals being down the ladder from men. Yet birds and men would of course both have an innate desire for food. The addition of evening showers is important in further establishing season—late autumn or early winter—and mood: the birds would be seeking shelter under the eaves from the cold rain, just as monks would be doing in the dining hall. In the end, Shikō’s conception is another example of karumi, or “lightness,” in the way it focuses on the common sparrow, whose twittering at the eaves in refuge is really little different from the monks inside the hall chatting over their food, all with evening rain coming down outside, imbuing the scene with sabi. The fact that by custom the monks would leave some of their precious fare to be set out for their animal neighbors strengthens the metaphorical bond.

KAWAI KENPŪ 河合見風, Kagetsu ichiyaron (One night with Kyōka and Chigetsu, 1765?) (p. 81)

There is nothing all that difficult about haikai. You just put your evening chats about the heat or the cold into a verse of seventeen syllables.

|

Such coolness! |

suzushisa ya |

|

An inner sanctum unknown |

hotoke mo shiranu |

|

even to Buddha. |

ushirodō |

|

Kenpū |

In terms of the outer scriptures, haikai consoles, while in terms of the inner scripture it soothes the seven emotions. You take what is before your eyes and evoke the forms of mountains, rivers, bays, and seas and the sights of flowers, birds, wind, and moon, everything down to people planting barley in the fields or rice in the paddies.

CONTEXT: Kawai Kenpū (1711–1783), of the Kaga domain, was a student of the Bashō school who also studied waka under a master of the Reizei house. This commentary on his hokku, from a treatise of uncertain origins titled Kagetsu ichiyaron, begins with two important contentions: first, that haikai is accessible to anyone, and second that its proper subject is everyday life. Then comes Kenpū’s hokku, offered as an embodiment of those assertions in its evocation of the everyday experience of coolness, followed by a claim that goes back as far as the Kokinshū preface—namely, that poetry should console and soothe by observing the patterns of nature and human affairs.

COMMENT: In all these ways, the comments here claim adherence to old traditions. The reference to the “outer” Confucian classics and the “inner” Buddhist scriptures also connects to the primary moral discourses of the time—the former offering teachings on how to regulate human affairs and the latter metaphysical insights into the nature of human existence and the hereafter. In various Buddhist texts the “seven emotions” are defined as happiness, anger, pity, pleasure, love, evil, and desire, which together define the range of human emotional phenomena, the transcendence of which is one fundamental aim of Buddhist enlightenment.

Kenpū’s hokku illustrates these claims by offering us not just a natural scene but also a proposition: that the experience of coolness, an everyday thing that virtually everyone has yearned for in the summer heat, offers enjoyment of the sort one might feel in a sequestered worship hall far back in a temple compound—the sort of place, needless to say, that normal people generally could not go. It is important that what the speaker claims is not intellectual—this is not a lecture by some cleric—but affective and sensory, the dai being coolness, not “enlightenment” or anything cerebral. Thus Kenpū elevates a simple bodily experience to the level of religious awakening. And to make his rather audacious claim more complete, he adds that such an awakening is not known even by the Buddha himself, a hyperbolic statement along the lines of the famous Zen advice, “If you meet the Buddha, kill the Buddha.” Buddha is not a vengeful god and does not mind being abused in the process of instruction.

YOSA BUSON 与謝蕪村, Buson kushū 128 (Spring): “Written for a gathering at the Bashō cottage”

|

While I broke ground, |

hata utsu ya |

|

that unmoving cloud— |

ugokanu kumo mo |

|

disappeared. |

naku narinu |

CONTEXT: After the death of his foremost disciples, Bashō’s reputation waned for a time, until a revival led by Yosa Buson (1716–1783), who began his career in Edo but gained prominence as a painter and poet in Kyoto during the 1770s. The cottage mentioned in the headnote was located in the grounds of Konpukuji, a subtemple of Ichijōji, a Zen temple in eastern Kyoto that Bashō had visited in his travels. Buson and his friends erected a cottage there in the master’s memory in 1776, where monthly poetry gatherings were held.

COMMENT: Buson was a professional painter, and many of his most famous hokku present static scenes that could be rendered in pictorial form. This hokku, however, involves a flashback of sorts: a plot, in narrative terms, albeit one that is highly elliptical. (Another of the characteristics of Buson is his evocation of short “stories.”) In spring, a farmer is out doing the backbreaking work of preparing soil for planting. After some time putting all his energy into that effort, he looks up from the fields and sees that the seemingly unmoving cloud that was in the sky when he began has now disappeared—a skillful way of representing the passage of time and the intensity of the man’s labor. What makes him look up we cannot say. Most likely it is simple fatigue, but one can also imagine that the departure of the cloud has allowed the sun to beat down more powerfully, removing the shadow under which he worked. In any case, the scene thus involves a central “absence” and duration of time that no painting could reproduce.

No doubt the bucolic surroundings of Konpukuji inspired Buson’s hokku, but it is not the only poem he wrote about farming. The lack of pronouns in hokku (a feature of Japanese discourse that is particularly conspicuous in poetry) presents the translator with a conundrum: should the perspective be first person, or third? Even if he did not spend time in the fields himself, Buson obviously could imagine himself in such a situation. And another poem, also from Buson kushū (A collection of Buson’s hokku, p. 61), seems more clearly to be written from the perspective of the laborer himself. (Or herself? The possibility cannot be denied, just as one must often leave open the possibility of a plural subject as well).

|

As I break ground, |

hata utsu ya |

|

I still see my house as day ends— |

waga mo ie miete |

|

but not for me. |

kurekanuru |

Pastoral scenes, often involving agricultural connotations, abound in waka anthologies, but it is in haikai that we see scenes of actual labor. Here the sky is growing dark, but as long as he can see his house through the gloom the farmer knows that he must make use of the light.

KYŪSO 旧礎 and OTHERS, Sabi, shiori (pp. 319, 325, 328, 329)

|

In every inlet, |

uraura ni |

|

boats not moving. |

ugokanu fune ya |

|

Summer rains. |

satsukiame |

|

Kyūso |

|

|

Penniless, |

zeni nakute |

|

I walk through autumn |

miyako no aki o |

|

in Kyoto. |

arukikeri |

|

Standing still |

furukawa no |

|

on an old riverbank— |

kishi ni shizukeki |

|

willow trees. |

yanagi kana |

|

It’s not as if |

nasu waza no |

|

my work is done. |

tsukuru ni wa arade |

|

Autumn dusk. |

aki no kure |

CONTEXT: Kyūso was from Kiryū in Kōzuke, and Kao, Sen’ya, and Ryūsui were all from Tajima. We also know that Kao’s lay name was Ashida Rokuzaemon and that he died in 1784 at the age of thirty-six. Sen’ya was probably not yet into his teens. Sabi, shiori (The “lonely” and “the bent and withered”) was compiled in 1776 by a man named Hanabinokoji Ichion (precise dates unknown), a disciple of Buson’s. After sections on pedagogy and some anecdotes, Ichion offers nearly a thousand hokku by students of Buson and his school, organized by region and author.

COMMENT: The hokku in Sabi, shiori are not arranged in seasonal categories but have season words, or kigo. The poems are thus not a sequence but a list of independent verses. Two of the ones here allude to autumn explicitly, and the other two have unequivocal kigo: satsukiame (rains of the Fifth Month) and yanagi (willows), an icon of spring.

Ryūsui’s poem has eight syllables in its second line, rather than the standard seven, but in haikai such slight departures were common, and in terms of rhetoric the poems are well within the boundaries of the Bashō school, each in its own way expressing the ideal of sabi. Kyūso depicts for us the essence of the feel of the rainy season via the image of boats moored in harbor, unable to brave the weather; and Sen’ya’s poem likewise presents us with a scene of natural beauty and feeling. The poems of Kao and Ryūsui, however, show us harsher vignettes of life: a man walking “penniless” through the streets of Kyoto, suggesting circumstances more moving because undisclosed, and a worker whose labors do not cease with the setting sun. The willows in Sen’ya’s verse offer a little color, but only against the backdrop of an “old riverbank.”

ARII SHOKYŪNI 有井諸九尼 and OTHERS, Akikaze no ki (p. 623)

Fourth Month, thirteenth, fourteenth. Passed over Nasu Moor. The autumn fields were unimaginably broad, and just the grasses and flowers we recognized were beyond counting. Standing there, I wrote,

|

Were you to speak, |

mono iwaba |

|

what would your voice be like? |

koe ika naran |

|

Maiden flowers. |

ominaeshi |

|

Shokyūni |

CONTEXT: Arii Shokyūni (1714–1781) was born in Kyushu to a village headman. In her teens she entered into an arranged marriage, as per prevailing custom, but no children came from the union, and around the age of twenty-six she ran away to Kyoto with a itinerant physician and haikai poet. After he died in 1762, she became a Zen nun and determined to live as a haikai master herself. In 1771, she set out with a priestly traveling companion to visit sites described in Bashō’s Oku no hosomichi (The narrow road through the hinterlands, 1694), documenting her journey in Akikaze no ki (A record of autumn wind, 1772). It chronicles her journey from her home in the Okazaki area of Kyoto, to Edo, Matsushima, and Miyagino, and other places, with long stops along the way.

COMMENT: Shokyūni’s hokku brings to mind a poem by Bashō’s traveling companion, Kawai Sora (1649–1710), about a little girl they met in the fields named Kasane, which the men imagine refers to an eight-pedaled variety of wild pinks (nadeshiko). Shokyūni’s maiden flowers (prominent in poetry since ancient times) do not come literally to life in the way Sora’s pinks do, but she suggests that we at least entertain such a possibility.

Akikaze no ki ends with a small anthology of hokku she collected along the way, among them a dozen by women, including these (pp. 627, 632).

|

If you stopped singing, |

nakariseba |

|

people could get to sleep— |

hito mo yoku nen |

|

cuckoo! |

hototogisu |

|

A warbler calls |

uguisu o |

|

and hearing its song |

kiku ya inochi mo |

|

extends my life. |

nagau naru |

Most women haikai poets of the Edo period were in some way connected to a male poet—as wife, sister, daughter, etc. In Shokyūni’s case, it helped that her second husband was a haikai master, and becoming a nun also eliminated some of the usual gender strictures. Some poems by women were gender marked, but mostly they aimed at broader human relevance that made them equals of men in the za.

BAIZAN 買山, Yahantei tsukinami hokku-awase (p. 418): “Water birds”

|

Water birds: |

mizutori no |

|

even chummier |

nao mutsumashiku |

|

in the rain. |

ame no naka |

CONTEXT: Baizan was from Fushimi, south of Kyoto proper. This poem was composed for a paper contest (not involving an actual meeting of all participants) held in the intercalary Tenth Month of 1786 by Takai Kitō (1741–1789; also known as Yahantei), a disciple of Buson’s. It is one of many such contests published by that master, which fulfilled one of his fundamental obligations; namely, getting his students—more than two hundred of them, mostly in Kyoto and its environs, where he had his practice and directed monthly meetings (tsukinamikai)—into print. The winning poems were “aired” in woodblock form, along with short critical appraisals by Kitō himself.

COMMENT: If ever one figure dominated a discourse, it is Matsuo Bashō. To this day most histories of haikai are structured around him, and his aesthetic values receive more attention than any others in his genre. But recent bibliographic labors have altered our understanding of Edo-era haikai in two ways. First, they make it clear that Bashō’s practice was eccentric in one way: most haikai professionals, of his and later eras, made their living through doing what Bashō abandoned after 1680—namely, direct tutoring and “marking” of student work. Second, they encourage us to look beyond Bashō’s hokku and travel writing to see him too as more engaged in an essentially social profession, even after 1680.

This leads us to pay more attention to poems like the one here from a later time, describing ducks huddling together in the rain. The dai in this case was waterfowl, and Kitō attached to it only one word of commentary, yūen, a variation on the ancient ideal of en, which means something like “beautiful and elegant.” Thus, in the world of haikai, we have a form, a venue, and a term of praise that link back to the world of waka and renga. Kitō’s comments on another example (Yahanteihan tsukinami hokku awase, pp. 358–59) from a monthly competition (dating from two years before), this one by a poet named Sha’en, make the connections just as obvious.

“Departing spring”

|

Lying ill, |

yameru mi no |

|

I am out of sorts |

ushirometaku mo |

|

at spring’s end. |

kure no haru |

COMMENT: The feeling of lying in bed, unable to see the colors of spring and resenting the passing of the season, is deeply moving [aware fukashi].

This example is not unusual: elsewhere Kitō employs other terms of praise used by Teika (and Bashō), including yūgen (mystery and depth) and yojō (overtones). Kitō had of course read Bashō, but he had also read the classics of the earlier tradition—as had Bashō, of course—from which the dai he assigned were often taken.

KOBAYASHI ISSA 小林一茶 and SUGINO SUIKEI 杉野翠兄, Issa Suikei ryōgin hyakuin

|

28 |

Fireflies—blown by wind |

hotaru fukichiru |

|

on Uji River. |

uji no kawakaze |

|

|

Suikei |

||

|

29 |

In moonlit darkness, |

tsuki kuraku |

|

thin trails of smoke rise |

sukumo no keburi |

|

|

from husks of reed. |

taedae ni |

|

|

Issa |

||

|

30 |

The wife of an outcast |

eta ga kanai ga |

|

makes offerings to the dead. |

tamamukae suru |

|

|

Suikei |

||

|

31 |

Autumn crows |

mono kurau |

|

set to eat something, |

aki no karasu no |

|

|

cawing away. |

sakebu koe |

|

|

Suikei |

||

|

32 |

In dappled dusk light— |

hi no chirachira ni |

|

skiff left on the bank. |

kishi no sutebune |

|

|

Issa |

||

CONTEXT: Kobayashi Issa (1763–1827), who in Japan is second in popularity as a haikai poet only to Bashō, is known for his attention to little things. His contemporary, Sugino Suikei (1754–1813), was an oil dealer living in Ryūgasaki (modern Ibaraki Prefecture). The sequence the two men composed together is an example of a duo sequence (ryōgin).

COMMENT: These verses from a duo sequence show that techniques established by renga masters persisted. In verse 28 we see fireflies along Uji River, to which Issa in verse 29 adds a time of day and human inhabitants. Then Suikei redefines Issa’s “moonlit” night as the time of Obon, the festival of the dead, when even tanners and other people in “unclean” occupations visit family grave sites with offerings. Linking to his own verse, Suikei then produces a nioizuke, or “link by suggestion,” that conjures up crows, defined as “unclean” because they eat carrion, in response to the idea of outcasts. Finally, Issa in verse 32 shifts away from Suikei’s bloody tableau by the technique of keikizuke, using simple apposition to pivot us away from foraging crows to a boat left on a riverbank in evening light, a more elegant scene, surely, and a classic example of a yariku, or “kind” link that would make it easier for the sequence to go in a new direction.

TOKOYODA CHŌSUI 常世田長翠, Ana ureshi (p. 324)

|

Barn swallows. |

tsubakuro ya |

|

How readily today |

kyō wa kinō ni |

|

becomes yesterday. |

nariyasuki |

CONTEXT: Tokoyoda Chōsui (1753–1813) was a disciple of Kaya Shirao’s, whose cottage in Edo he inherited. A native of Shimōsa Province, he left Edo and settled at Sakata in Dewa during his later years.

COMMENT: Most hokku present visual scenes, small narratives, or propositions, rather than anything philosophical. Here, however, Tokoyoda Chōsui uses simple apposition to suggest the continuity of time. The poem relies on no standard word associations, metaphors, or other rhetorical devices, presenting only a concrete noun and an abstract statement. As in a link, the first line connects to the final two lines through suggestion, or “scent” (nioi).

What qualities of barn swallows suggest the flow of time? In the canons of haikai, the word “swallow” indicates spring as a season, a time when the natural world is going through a transition; and we know that swallows often build nests for their young in liminal spaces such as the eaves of houses and outbuildings. Furthermore, we notice them in the morning or the evening, as the human day is undergoing a temporal change. Finally, the word yasushi, “readily” or “nonchalantly,” might relate to their instinctive behavior, which stands for the seemingly seamless and untroubled order of the natural world.

The use of apposition is a feature of many of the poems in his personal collection, Ana ureshi (Ah, a delight, 1816, pp. 322, 327, 330):

|

Spring day. |

haru no hi ya |

|

Two people walk together |

tsu no machi suguru |

|

through a port town. |

futarizure |

|

Full moon. |

meigetsu ya |

|

Yesterday the priest |

sō wa kinō no |

|

was a temple boy. |

chigo narishi |

|

A snipe cries. |

shigi naku ya |

|

Gone in passing wind, |

kaze ni kietaru |

|

a sandy path. |

suna no michi |

This is a world of experience rather than abstract “meaning.” Each poem offers juxtapositions that present a transition in time followed by a noun participating in that transition while also remaining static or stationary. One can imagine dramatic contexts (a wandering, a young monk looking at the moon with companions, someone lazily watching passersby on a spring day). But as they are, the poems offer only parataxis—statements not linked by grammar—and leave further combinations to the mind of the reader. The technique would become prominent in the twentieth century.

NATSUME SEIBI 夏目成美, Sumika o utsusu kotoba (Moving into a new house, 1814, p. 276)

The place I was moving to was near the entry gate in Asakusa, where I had once lived long before. Located where the Sumida River empties into the bay, along the Kamida River, the place was entirely surrounded by shopping districts, right next to the famous Sensōji Temple. In old age, a person would usually withdraw to a more tranquil place, although there are perhaps many who would prefer the opposite.… Someone told me that having lived so long in solitude I would not be able to stand city noise, but I answered that I would act like an old silkworm and think of the time I had left as time to enjoy.

|

So short a night! |

mijikayo wa |

|

Doing this, doing that— |

tote mo kakute mo |

|

time goes by. |

sugusu beshi |

CONTEXT: Natsume Seibi (1749–1816) was unusual in having no primary teacher and truly walking his own way, although he had contact with a number of the poets of his day, most especially Kobayashi Issa. In his sixty-sixth year, Seibi moved from Katsushika, outside the city, to the bustling Asakusa district of Edo, at the request of his children, who were providing his everyday needs.

COMMENT: The son of a wealthy rice broker, Seibi had lived in Asakusa in his youth, but still the adjustment was not easy. In a hokku from the same text (p. 276) he opines that even the most common sounds seem different in a new place.

|

All I hear |

kiku koto o |

|

I must hear anew— |

mina aratamete |

|

even the cuckoo. |

hototogisu |

Lame and elderly, Seibi was mostly housebound, and distance made it difficult for him to visit old friends in Katsushika, where he had lived for a decade. As commentary on his new situation, Seibi uses an old phrase, mijikayo wa, “So short a night!” Usually that phrase is used in love poems, lamenting the swift passing of a summer night, in words uttered at parting. And Seibi had in fact moved on the sixth day of the Fourth Month of 1814, at the beginning of summer according to the old calendar. But his poem contains no hint of love as a category; rather, it presents the trope of an aging person awake in the night. And he builds on that idea to suggest another connotation of mijikayo: the inevitability of time’s passage, for everyone, old and young alike. The sugusu beshi of the last line is emphatic: time will pass by. His ten years in another house are now no more than a dream, and the time back in the neighborhood of his childhood will pass just as quickly. In the summer of the following year, he would write in a colophon to Haikai nishi kasen (A western kasen, p. 202), “I waste away, prey to every malady, as with each passing year more of my friends die.” On the nineteenth day of the Eleventh Month of 1816 he passed away, at his house in Asakusa.

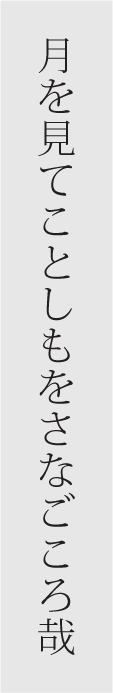

ŌSHIMA KANRAI 大島完来, Kūgeshū (p. 459) (Autumn): “Not praying for a long life”

|

I see the moon |

tsuki o mite |

|

and this year feel again |

kotoshi mo osana |

|

like a little child. |

gokoro kana |

CONTEXT: Ōshima Kanrai (1748–1817; also known as Kūge), born in Tsu Province, was known also by the sobriquet Setchūan the Fourth, signifying that he was the poetic heir of Ōshima Ryōta (1718–1787), master of one of the largest and most prominent haikai schools of the eighteenth century. Although Kanrai had begun life as a samurai in Ise, he left that life to come up to Edo to pursue a literary career. He took over Ryōta’s Edo practice upon the latter’s death in 1787.

COMMENT: The later poems of Ryōta are known for their plain style, and Kanrai’s poem is straightforward in that same way. Moon gazing, usually an autumn activity, had been a custom since ancient times, and coming up with a new variation on such an image was a challenge. Kanrai approaches the idea directly, alluding to the moon openly in his first line and then telling us simply how the experience makes him feel. Just as Bashō said that cherry blossoms “call many things to mind,” Kanrai finds that the sight of the moon makes him feel as if he were transcending time, feeling again like he did as a child. To complicate his scheme somewhat he employs the particle mo, meaning “again, just like before,” and with that one syllable extends our vision back across all the years since we first noticed the moon in our youth. While we pass through our lives below, taking on years along the way, the moon, always distant, clear, and cool in demeanor, remains the same.

For Kanrai to leave his living in Ise and opt for life as a haikai poet amounted to a religious renunciation of lay life, following a pattern set by medieval poets such as Tonna and Sōgi and later also by Bashō. In an explicitly Buddhist poem from his personal anthology, Kūgeshū (Kūge’s collection, 1820, p. 456), Kanrai makes the identification of priest and poet explicit:

|

Born in the world, |

umaruru ya |

|

Buddha, Bashō, both— |

shaka mo bashō mo |

|

dew on the grass. |

kusa no tsuyu |

The headnote to this poem says it was written at a tea gathering, another art that was also considered a religious michi, or “Way.” One thing that all these arts shared in Buddhist terms was a strong sense of the ephemerality of existence in the world. To borrow the metaphor of the second poem, such events shared the lot of all human activities, which in cosmic time last no longer than dewdrops on the grasses—grasses that are seasonal themselves and that will wither and decay as the season progresses. In this sense, the Buddha, the great master Bashō, the dew, and the grasses all teach nonduality: all distinctions being only temporal, and all things ultimately empty. Perhaps it was with this in mind that his disciples chose the title “Flowers of Emptiness” for Kanrai’s collected poems.

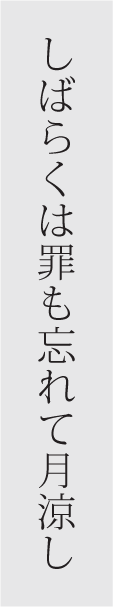

TAGAMI KIKUSHA 田上菊舎, Oi no chiri (p. 31)

|

For a while |

shibaraku wa |

|

I forget even my sins. |

tsumi mo wasurete |

|

So cool, the moon! |

tsuki suzushi |

CONTEXT: Tagami Kikusha (1753–1826) was the daughter of a physician in Nagato. She married at age sixteen, but when her husband died just eight years later, she became a nun and poet. Because of the premature death of her husband when she was still in her midtwenties she ended up living as a poet and devotee of the True Pure Land sect of Buddhism who also practiced the art of the tea ceremony. This poem was written early in the Sixth Month of 1780, near Zenkōji Temple (Nagano Prefecture), out of gratitude to a farm couple who had given her shelter.

COMMENT: At the time she wrote her poem, Kikusha was following in the footsteps of Matsuo Bashō in his Oku no hosomichi, taking notes for her own travel record, Oi no chiri (Knapsack dust, 1782). Yet the content of her poem suggests that her motives were as much devotional as artistic, and the many anecdotes she records about mercies extended to her on the road portray her journey as a pilgrimage. As a True Pure Land nun she believed in the bodhisattva Amida, whose name she recited in the nenbutsu (“Savior Amida—All Hail!”) as a plea for grace, and we are not surprised that her poem offers a moment of respite provided by a beautiful moon that she says can make us forget—although only briefly, of course—both the summer heat and a world of sin. The moon shining in the darkness of night was frequently employed as a metaphor for Buddhist enlightenment. Here it also stands for the kind ministrations of strangers.

Her travel diary Taorigiku (Hand-picked chrysanthemums, 1812, p. 161) records another poem she wrote around the same time that ends with the same line.

|

At Crone’s Crag |

ubaishi o |

|

I take strength late at night. |

chikara ni fukete |

|

So cool, the moon! |

tsuki suzushi |

Crone’s Crag (ubaishi) was a local landmark, a large hump of rock resembling a bent-over old woman that resonates with stories of old people left to die on the slopes of nearby Obasute Mountain. Kikusha decided the next day to climb the mountain trail, where a rainstorm forced her to take shelter between huge boulders, quite literally bent over like Crone’s Crag. Fortunately, she was able to “take strength” the next day from another merciful farm family. Kikusha’s travel diary documents a whole network of monks, nuns, artists, and poets in villages she traveled through, but she also introduces “people of feeling” (nasake shiru mono) from the lower classes. The cool moon of summer, she suggests, shines down on high and low alike, while her identification with Crone’s Crag serves as counterpoint, to accentuate the distance between the cool moon above and the fallen world below.

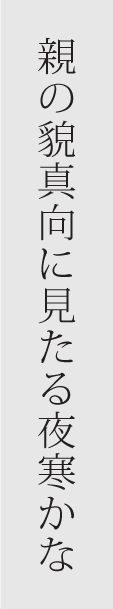

SHIMIZU IPPYŌ 清水一瓢, Gyoku sanjin kashū (p. 444): “This year, at the beginning of the Long Month, I left Asakusa … and traveled to Honmoku and on to Sugita, where I made offerings at the grave of my father”

|

Beside her, |

oya no kao |

|

I stare at Mother’s face |

mamuki ni mitaru |

|

in night’s chill. |

yosamu kana |

CONTEXT: Shimizu Ippyō (1770–1840; also known as Gyoku Sanjin, hence the title of his personal collection, Gyoku Sanjin kashū), a priest of the Nichiren sect, began his career at Hongyōji in Edo and ended up retiring there after being employed at other temples in Mishima and Kyoto. He was acquainted with both Issa and Seibi. This poem was composed in the “Long” Ninth Month in 1810, when he was visiting his mother in Sugita (now in Yokohama).

COMMENT: Many hokku offer the reader objective description, but more intimate feelings are not necessarily proscribed. This seems particularly true when it comes to the experiences of illness, old age, and death. In the following, Bashō (Nozarashi kikō [Bones bleaching in the fields], p. 291) writes movingly of seeing a lock of his late mother’s hair, as does Issa (Chichi no shūen nikki [A record of my father’s death], p. 424) of his father’s last moments and Seibi (Seibi hokkushū [Seibi’s hokku collection], p. 5) of taking his children to visit the grave of their mother four years after her death.

|

Held in my hand |

te ni toraba kien |

|

it would melt in hot tears— |

namida zo atsuki |

|

autumn frost. |

aki no shimo |

|

Bashō |

|

|

From his sleeping face |

nesugata no |

|

I brush the flies away— |

hae ou mo kyō ga |

|

today, one last time. |

kagiri kana |

|

Issa |

|

|

Pointless, |

ko o tsurete |

|

dragging my kids along. |

yuku kai mo nashi |

|

Frost-covered grave. |

shimo no haka |

|

Seibi |

|

Thus haikai continues the memorial traditions of waka and renga, albeit with more realistic imagery and more colloquial rhetoric. Ippyō’s poem concentrates on his mourning mother’s face. And what does he see? The signs of old age, no doubt: wrinkles and weathered skin; gray hair, or white; and signs of loss and weariness in the eyes. But all of this must be our contribution to the reading process. A lock of white hair, flies buzzing around a sleeping countenance, a frost-covered gravestone—all are examples of synecdoche, or parts standing for wholes we must imagine for ourselves. Ippyō’s concluding “night’s chill” (yosamu) likewise stands for more than autumn cold.

INOUE SEIGETSU 井上井月, Seigetsu kushū 436 (Summer)

|

Late into night, |

fukete kite |

|

knocking at the inn. |

yado o tataku ya |

|

Summer moon. |

natsu no tsuki |

CONTEXT: Seigetsu (1822–1887) was of samurai lineage, but one document says he went into poetry when faced with the prospect of farming for a living, perhaps reflecting the disenfranchisement of the warrior class that took place at the time of the Meiji Restoration. He was born in Nagaoka (modern Niigata Prefecture) in Japan’s snow country but later lived in nearby Ina, Shinano Province (modern Nagano Prefecture), near Zenkōji Temple. From his late teens on he dedicated himself entirely to haikai, taking the tonsure, as was the custom among haikai devotees, and traveling to Edo and the Kansai. A twentieth-century compendium of his work, Seigetsu kushū (Seigetsu’s hokku collection), contains nearly thirteen hundred of his hokku, along with a short treatise on poetry.

COMMENT: Scholars offer us little help in interpreting the poems of Seigetsu, a little-known regional poet. The poem here, however, asks us only one question: is it the summer moon knocking on the door, figuratively, or an actual traveler? In either case, someone is called to the door by knocking; and in either case our eyes are drawn up to an aloof moon. Like many haikai poets, Seigetsu thought of travel as an avocation and knew what it was like to be on the other side of the door with the hope of lodging.

Seigetsu passed away, still in obscurity, before Masaoka Shiki began a campaign to reclaim haikai as a poetic genre for a new age. Shiki had harsh words for Bashō, instead championing the works of Buson as models of what he called shasei, or “sketching from life.” Not so Seigetsu, who participated in memorial services for Bashō and revered him above all poets. One anecdote says that when asked for a copy of Bashō’s famous prose piece Genjūan no ki (Record of life in Genjū Cottage, 1690), he was able write it out—producing four tightly packed pages—from memory.

In response to Bashō’s famous hokku (Oi no kobumi, p. 312)

|

A traveler, |

tabibito to |

|

that’s what I’ll be called. |

waga na yobaren |

|

First winter rains. |

hatsushigure |

Seigetsu wrote an allusive variation (referred to as honku in haikai discourse) that is unequivocal in stating his desire for affiliation with Bashō as a model for life and practice (Seigetsu kushū, no. 269).

|

Count me, too, |

tabibito no |

|

among the travelers. |

ware mo kazu nari |

|

Cherries in full glory. |

hanazakari |

Records of his time sometimes refer to him as Unsui Seigetsu—Seigetsu, the Wandering Cloud—indicating that he got his wish.

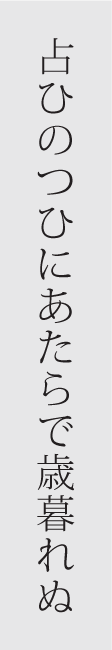

MASAOKA SHIKI 正岡子規, Shiki zenshū (3:312)

|

That fortune-teller |

uranai no |

|

was wrong, it seems, |

tsui ni atarade |

|

as the year ends. |

toshi kurenu |

CONTEXT: Masaoka Shiki (1867–1902) is the most famous of all modern poets in both tanka (the modern word for waka) and haiku, the latter being the word he insisted upon for modern hokku in order to signal a break with traditions of the past. His poem dates from the winter of 1897, when he was suffering with the spinal tuberculosis that would take his life five years later, in his thirty-fourth year.

COMMENT: Even in modern times, many haikai dai relate back to earlier poetic discourse. For instance, the “Winter” book of every anthology of waka concludes with poems on “the end of the year,” a dai that for centuries inspired laments such as the following from Taikenmon’in Horikawa shū (A collection of poems by Taikenmon’in Horikawa), no. 69, by a late Heian-era lady-in-waiting:

|

What was I thinking, |

mukashi nado |

|

when in the past I hurried |

toshi no okuri o |

|

to see a year off? |

isogiken |

|

As the years keep adding up, |

tsumoreba oi to |

|

I get older—that is all. |

narikeru mono o |

Our readiness to see the old year off, of course, comes in anticipation of the celebration of the New Year, still today the most important holiday in Japan. But human beings do not truly begin again each year with the calendar and are thus out of sync with the “rebirth” of the natural world, the poet reminds us. For us a new calendar does not truly bring new life.

Shiki’s poem is more elliptical and less earnest than Lady Horikawa’s, but the two share a sense of foreboding. Shiki, however, was not facing old age but death. He had nearly died in the spring of 1895, and one wonders how hopeful he could have been at the beginning of 1897. But the reading he got from the fortune-teller must have been something more positive than what he actually experienced as the year went on. And it appears that he was no happier the next year, when he wrote another poem (also from his complete works, Shiki zenshū, 3:404) on the same idea.

|

As if laughing |

ningen o |

|

at us, we human beings— |

warau ga gotoshi |

|

the year just ends. |

toshi no kure |

Oblivious to our feeble attempts to control it, time just goes by, Shiki says. Shiki faulted Bashō for sentimentality, and in these poems he perhaps shows us what he meant. Fortune-tellers are not the only deceivers, he suggests; we all deceive ourselves by concocting silly conceptions like seasons that mock us as we mistake time’s derision for smiles.

NATSUME SŌSEKI 夏目漱石, Natsume Sōseki nikki (p. 198)

My two brothers died young, and with not a white hair on their heads. Yet here I am, the hair at both my temples going white, as the thin thread of my life just stretches on.

|

Still I live, |

ikinokoru |

|

ashamed of the frost |

ware hazukashi ya |

|

at my temples. |

bin no shimo |

CONTEXT: After a stint as a professor of English literature at Tokyo Imperial University, Natsume Sōseki (1868–1916) went on to write some of the finest novels of the twentieth century, but he also was a close friend of Masaoka Shiki’s and wrote haiku. Information from Sōseki’s diary (nikki) tells us that from August to October of 1910, he was convalescing at the Kikuya Inn at Shūzenji Temple in Izu, suffering from the effects of a bleeding ulcer. This poem comes from his diary, September 14, when he was spending most of his time in bed.

COMMENT: Photos of his time at Shūzenji show an emaciated figure with flecks of white in his hair, and another poem written around the same time (Nikki, p. 198) makes it clear that he felt as if the end might not be far off.

|

Ill on the road, |

tabi ni yamu |

|

my heart feels night’s chill— |

yosamu kokoro ya |

|

wanting sympathy. |

yo wa nasake |

A literal translation of the last line of this second haiku would read, “In the world, [we need] sympathy,” and it comes from a famous saying, “On the road, one wants a companion—just as in the world one wants sympathy” (tabi wa michizure, yo wa nasake). One cannot help but wonder if he was thinking of Shiki, gone now eight years, who would have been a comfort on his journey. And we can be certain Sōseki had in mind Matsuo Bashō, from one of whose last poems (Oi nikki [Knapsack diary], p. 269) he took his first line:

|

Ill on the road, |

tabi ni yande |

|

I wander in my dreams |

yume wa kareno o |

|

in barren fields. |

kakemeguru |

In an essay about his experience at Shūzenji, Sōseki wrote that writing haiku and Chinese poems during his illness brought him a welcome sense of release from the obligations of normal life (Omoidasu koto nado [Things I remember], 1910, pp. 14–17), but the “night’s chill” of the second line would seem to reveal darker forebodings. Six years later, on December 9, his bleeding ulcer finally took his life. His last recorded haiku date from just a month before.

YOSHIYA NOBUKO 吉屋信子, Yoshiya Nobuko nikki (pp. 277–78): August 1945

August 15. Clear. Notice goes out that His Supreme Highness the Emperor himself will make a broadcast noon today. Feels like a weight bearing down on my chest …

At noon, His Highness, for the first time in his own voice, says that the war is coming to an end. I sit in front of the radio, weeping. Hearing the anthem “His Majesty’s Reign” was very sad.

The newspaper came at five and I read it. “Lots of imperial warplanes in the skies—sirens blaring—seven warplanes shot down.” Such were the reports.

At 11:40 came the final broadcast over the military news.

|

Cicadas crying, |

semi mo naki |

|

people crying, too. |

hito mo nakikeri |

|

Today, at noon. |

kyō mahiru |

CONTEXT: Yoshiya Nobuko (1896–1973) was a romance novelist who wrote openly as a lesbian and was one of the most popular writers of her time. She was an avid practitioner of haiku and a fixture among poets of the form in Kamakura.

COMMENT: Many writers have recorded their reactions to the broadcast in which the emperor himself announced defeat at the end of World War II, often noting how difficult it was to understand the emperor’s arcane vocabulary. From her diary (nikki), we know that Yoshiya Nobuko evidently understood right away. Like many others, she was relieved but also worried about the future as she listened to the national anthem. The drone of the cicadas, a conventional kigo, or “season word,” often symbolizes the universal ephemerality of mortal existence, not an inappropriate reference at the time in question; but the addition of human voices, crying not in the night but at midday, makes the poem into a more poignant lamentation over the events of a specific time and place.

A few days later Yoshiya’s diary tells us that she attended a haiku gathering at nearby Tsurugaoka Shrine with a number of other writers of the Kamakura community, including Kume Masao (1891–1952), Satomi Ton (1888–1983), Nagai Tatsuo (1904–1990), and others. The group strolled through the grounds of the shrine and found no other people about. Nobuko says that she thought to herself that maybe now that the war had ended it might be possible to begin writing again. The haiku she composed on that stroll (p. 279) is simple on the surface but gains in significance when considered in its historical context.

|

Only leaves now |

ha bakari no |

|

on the lotus pond, yet— |

hasuike naredo |

|

I stop to look. |

mite orinu |

Lotus flowers, another kigo, symbolize Buddhist enlightenment. Stopping to gaze on a summer pond where the flowers have not yet appeared she can only have been reflecting about what might be coming in the future, and not only for the pond.

NAGAI KAFŪ 永井荷風, Kafū haikushū 731

|

A peony falls |

botan chitte |

|

and again I hear rain |

mata ame o kiku |

|

outside my hut. |

iori kana |

CONTEXT: Nagai Kafū (1879–1959) was groomed for business by his father but refused to cooperate. He began as a writer of the naturalist school but went on to write elegies for the grimy alleyways of Tokyo. He also left behind more than eight hundred haiku, the first in 1889, the last in the mid-1950s. In April 1946, when this poem (from the standard collection of his haiku) was written, he was living in Sugano, Ichikawa City.

COMMENT: During World War II, Nagai Kafū published little, but he did keep a diary, where he occasionally complained about the Japanese government. Nor did the war’s end not stop him from grumbling, as evidenced by the words he jotted down before recording this haiku on April 28, 1946. The quality of the tobacco being rationed is so bad that it has put him off smoking, he frets, and to make matters worse, the soy sauce isn’t salty enough and the miso carries an unpleasant odor—“Conspicuous signs, one must think, of how the nation marches on toward its downfall.”

The haiku included here was written one evening at the request of a doctor who was treating Kafū at the time. The pose Kafū adopts is the hoary one of the recluse in his hut of grass. What the speaker is distracted by we do not know—his books? His memories? For whatever reason, he is preoccupied until a falling peony flower interrupts his reverie, drawing attention to what is going on outside. For readers the poem “unfolds” in a conventional but effective way. We begin with the image of a flower falling—a peony, a season word indicating summer—and the rain coming down outside, and only then learn the location of the speaker, an iori, or “hut.” Thus, in a common ploy, the speaker offers an image that may at first register as visual but then envelops us in sounds—first the heavy “plop” of a peony flower and then the pitter-patter of rain.

By this time Kafū was already publishing stories again—although he could not have known how prominent he would become in the immediate postwar era, when his reputation benefited greatly from his erstwhile belligerence toward the military regime. It is worth noting that after complaining about the tobacco and food he goes on to ridicule the Japanese people at the time for seeking solutions for the present crisis in superficial mimicry of “other cultures,” naming China and the West. As the peony was an import from China, one is tempted to undertake a metaphorical reading of his haiku, but that would doubtless be going too far. It appears in Japan as early as The Pillow Book of Sei Shōnagon (early eleventh century).

That Kafū put thought into his haiku is apparent from the fact that we have differing drafts. Next to the one here in his composition notebook (Sōsaku nōto) is this one (no. 732) that has the same feel but is less clever.

|

A peony falls |

botan chitte |

|