Detail from Edo-period illustration of Wakan rōeishū, an early eleventh-century anthology of poems in Japanese and Chinese.

Courtesy L. Tom Perry Special Collection, HBLL, Brigham Young University.

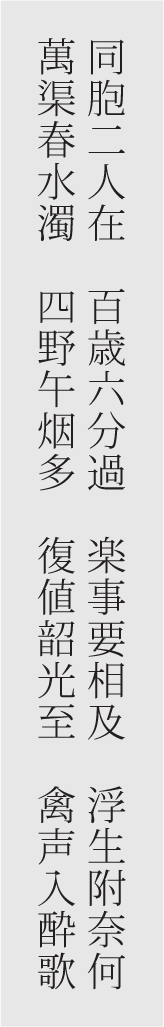

PRINCESS UCHISHI 有智子内親王, Honchō ichinin isshu 145: In Response to Emperor Saga’s “Mount Wu Looming High”

Mount Wu is lofty, its slopes sheer;

I gaze upon it—ah, how high it towers!

Peaks of green and waters ocean-blue loom ahead;

from deep purple skies streams gush down.

Dark clouds engulf all at morning;

incessant rains pour down at dusk.

And there is more: monkeys crying at dawn—

cold voices in the limbs of old trees.

CONTEXT: Uchishi Naishinnō (807–847) was the daughter of Emperor Saga (786–842). She served as Virgin at Kamo Shrine from 810 to 831. Unusually for a woman of her time, she was known for her Chinese poems. The Mount Wu (Wushan) of her poem, located in the Yangtze Gorges, has been known since ancient times as a place of mystery and legend. She most likely knew of it from a rhapsody (fu) by Song Yu (ca. 319–298 BCE). That poem tells of how King Xiang, visiting Gaotang Shrine with Song Yu, was out walking when he saw a pillar of mist rising from a shrine on the mountain. Song Yu then told the story of a former king who, while staying in that same area, was visited by a divine maiden in a dream, who lay with him and the next morning told him that she could not tarry, but that he should remember her when he saw the clouds on Wushan in the morning and the rain in the evening. After hearing the story, Song Yu wrote his rhapsody, which paints Mount Wu complete with tigers, dragons, alligators, and wizards.

COMMENT: Princess Uchishi’s poem (an example of lüshi, “regulated verse”) begins with the mountain, which for her existed only in the imagination. She then enumerates peaks, rivers, waterfalls, and the obligatory clouds and rain, referring only vaguely to the mystery of the site. Her final couplet adds just one thing to the scene: “monkeys crying at dawn—/ cold voices in the limbs of old trees.” Hers is a starker landscape that evokes a hidden world via a technique similar to allusive variation (honkadori) in waka.

Emperor Saga’s court produced a great deal of Chinese poetry. Uchishi’s half brother, Crown Prince Masara (808–850; later Emperor Ninmyō), also showed talent. His “Snow Falling in a Quiet Courtyard” (no. 141 in Honchō ichinin isshu, a late seventeenth-century collection of Chinese poems by Japanese poets) was written when he was seventeen. It offers description and is similar rhetorically, but without any mythological overtones.

Dark clouds gather on the myriad peaks;

white snow floats on winds in the palace grounds—

falling damp but freezing harder still on the flagstones,

soundlessly, calmly descending from the sky.

Cinnabar it cancels out, making all white,

painting over differences, making all the same.

Sitting quietly, I observe this by myself,

as the stones disappear from sight.

PRINCE SUKEHITO 輔仁親王, Honchō ichinin isshu 261: Woman Selling Charcoal

Just now I heard her—an old lady peddling charcoal;

her village is far away, off in the Ōhara hills.

In thin robes she climbs steep slopes, harsh winds at her side;

under cold skies at dusk she heads home, moon in front of her.

Amidst white snow, she raises her voice at crowded crossways;

in the autumn wind, prices go up among ramshackle houses.

For what she sells, most favor buying from a stout young man;

how one pities her, seeing those white flecks in her hair.

CONTEXT: Sukehito Shinnō (1073–1119) was a prince who did not succeed politically and in his last decade lived in seclusion, writing poetry in both Chinese and Japanese. His lüshi offers a variation on “The Charcoal Seller: An Attack on the Purchasing Tactics of the Palace” by the Tang poet Bai Juyi, who was especially popular among Japanese courtiers.

COMMENT: Bai Juyi’s work is social critique, presenting an old man herding an ox loaded with charcoal pursued by palace agents who force him to sell his cargo for a pittance. Sukehito’s poem is a variation on that idea that presents us with an old woman and says nothing about an ox or a cart. And rather than being stuck on a muddy road, we see her hawking her charcoal through the streets. Only the last line contains a hint of critique in suggesting that she suffers because of her gender and age. The poem also presents the name of a famous place—Ōhara, northeast of Kyoto proper. All the major images associated with the period when autumn is becoming winter in court poetry are presented: harsh winds, cold skies, snow, and autumn wind, adding the moon to indicate time of day.

Many poets wrote both kanshi and waka and some renga as well, so one wonders if the renga master Shinkei had Sukehito’s poem in mind when he composed his famous scene (Chikurinshō, no. 1258) of a charcoal seller too poor to afford his own products:

|

A pitiful sight: |

aware ni mo |

|

smoke rising at evening |

mashiba oritaku |

|

from a brushwood fire. |

yūkeburi |

|

His charcoal sold at market, |

sumi uru ichi no |

|

a man heads back into the hills. |

kaerusa no yama |

The first verse here includes the word aware, which Sukehito uses in its verbal form, awaremu, and his scene seems closer to the mood of Sukehito’s than to that of Bai Juyi. The better conclusion, however, is that Shinkei was aware of both scenes, which hover together around the edges of his ink-wash tableau.

HINO TOSHIMOTO 日野俊基, Honchō ichinin isshu 326: Before Execution at Kuzuhara Hill in Kamakura

The saying is ancient:

there is no death, no life.

For ten thousand li clouds dissipate;

the Yangtze’s waters flow clear.

CONTEXT: Hino Toshimoto (d. 1332) was a scholar in service to Emperor Go-Daigo (1288–1339), in whose rebellion against the warrior government he was implicated—not just once, but twice. The first time he escaped death, but when another plot was revealed he was not spared. He was executed in the Sixth Month of 1332 at Kuzuharagaoka in Kamakura.

COMMENT: This poem is an early example of a jisei no ku, or “death poem.” Often such poems are of dubious origin, but some accounts do show people writing such didactic poems immediately before death, on the battlefield or the execution grounds. Toshimoto evidently wrote two, the Chinese poem here and a waka recorded on a plaque at Kuzuharagaoka Shrine:

|

Before autumn has come |

aki o matade |

|

my life fades like a dewdrop |

kuzuharaoka ni |

|

at Kuzuhara Hill— |

kieru mi no |

|

though I leave some regrets |

tsuyu no urami ya |

|

behind me in the world. |

yo ni nokoru ran |

Toshimoto’s Chinese poem, a highly elliptical example of the shi form, begins with a statement of stoicism, evoking a grand image of the Yangtze River, meant to contrast with the insignificance of a single human life. As a scholar, he no doubt wanted to be remembered for his skill in Chinese, which the poem demonstrates. His Japanese poem, probably intended for family, is different indeed: here we encounter not stoicism but a hint of regret, expressed not in grand imagery but in a dewdrop.

Toshimoto had a brother, Suketomo, who was also involved in the 1332 plot and was also put to death, after banishment to the island of Sado in the Japan Sea. He, too, left a Chinese quatrain (Honchō ichinin isshu, no. 325):

The five aggregates achieved only fleeting form;

the four elements now return to nothingness.

I offer my neck to the white blade—

to be severed in one blast of wind.

Suketomo refers us to the Buddhist concepts of the five aggregates (goun), or skandhas—form, sensation, perception, mental formations, and consciousness—and then to the four elements of earth, water, fire, and wind. His final image is obviously meant to slice through all such distinctions. His Chinese poem is as stoical as his brother’s.

ZEKKAI CHŪSHIN 絶海中津, Shōkenkō 5: Waiting for a Friend Who Doesn’t Show Up

You promised to come and visit,

so night after night I fret, waiting for you.

Clouds and rain come fitfully—

rambling, staying or going as they please.

In mountain dusk, autumn’s voice comes early;

my attic room is empty, vapors deep around it.

In the quiet I sit, no one here to chat with me;

and my zither, it just hangs there on the wall.

CONTEXT: Zekkai Chūshin (1336–1405) was a priest who served at the very apex of the hierarchy of the Rinzai sect of Zen, which arrived in Japan in the late twelfth century and was of central political and cultural importance throughout the medieval period, especially among the military aristocracy. The name Gozan, “Five Mountains,” originated in China, where five Zen temples (“mountains”) were designated as preeminent. Nanzenji, Shōkokuji, and Tenryūji were among the designated temples in Kyoto, as were Kenchōji, Engakuji, and Jūfukuji in Kamakura. Many Zen priests traveled to China to study, often staying for long periods, and Zen temples quite naturally became centers of Chinese learning that produced many artists (the renga master Sōgi and the ink-wash painter Sesshū, for instance) as well as priests who wrote poetry, usually in Chinese.

COMMENT: Zen poems resemble waka of the same time in focusing on natural imagery but often employ less than elegant imagery. Sometimes the poems articulate religious ideas, while sometimes they reflect the Zen belief that enlightenment was to be found in the quotidian rather than in “otherworldly” experiences or rituals. Here there is no overtly religious symbolism at work, unless one thinks of the dusky autumn landscape as standing for oncoming decline and death. Alternatively, one might take the last lines as a statement of grudging stoicism.

Zekkai’s lüshi, from his personal collection (whose highly allusive title means something like “scraps of straw no more substantial than plantain leaves”), has a strong sense of speaker, as is often true in Gozan poems. Many Zen meditation exercises (kōan) presented quirky models of behavior, and those qualities shine through to one degree or another in many Gozan poems as well. In this case, however, Zekkai presents us with a very ordinary person in an ordinary situation, and one that reveals nothing about his own status. The trope of a lonely person waiting for a visitor who doesn’t show up appears frequently in court poetry as well. There the figure is a melancholy one, however, while Zekkai’s speaker is more whimsical. Essentially, the poem presents us with a complaint—“Are you no better than fitful clouds and rain? I wait here alone as autumn deepens, so depressed that I don’t even take down my zither to play.” Similar complaints are often found in love poems in the waka form, of course, but here the headnote tells us that it is a friend that the speaker waits for and not a lover.

The “attic room” probably refers to a small second-story chamber where friends might gather together to chat, write poetry, drink sake, and get a nice view of the moon.

SON’AN REIGEN 村菴霊彦, Chūka jakuboku shishō 142: From Afar, I See a House Where Trees Are in Flower, and Go Right In

Far off, I see them—peach trees, or maybe plums?

I go in the gate, not asking whose house it is.

While spring lasts, I am a crazy butterfly:

I go in, I pass by—all for the flowers.

CONTEXT: Son’an Reigen (1403–1488; also known as Kisei Reigen) was a Rinzai priest associated with Nanzenji. His poem, from a collection of poems by Chinese and Japanese monks compiled in the mid-1500s, is a kudai kanshi that takes a line from a Chinese poem as its topic, a practice as common in kanshi as in waka, where the device was called kudai waka. Reigen builds his quatrain (jueju) on a line from Bai Juyi recorded in Wakan rōeishū (no. 115):

From afar, I see a house where trees are in flower, and go right in:

rich or poor, known to me or not, it doesn’t matter.

COMMENT: While noting Bai Juyi’s verse, a commentary on Reigen’s poem by a Zen priest of the mid-1500s says the meaning (kokoro) of Reigen’s poem derives more from an allusion to the story of how the Daoist sage Zhuangzi falls asleep, dreams of being a butterfly, and after waking is not sure whether he is a man who dreamed he was a butterfly or a butterfly dreaming he is a man. In this way Reigen presents himself as a carefree spirit captivated by spring flowers. The speaker’s avowed indifference toward worldly hierarchies (“not asking whose house it is”) is again typical of Zen, and his dedication to aesthetic experience puts him in the lineage of the medieval priest Saigyō, who likewise declared his freedom (Shin kokinshū, no. 86) from the usual obligations of social life:

|

That pathway I marked |

yoshinoyama |

|

when last year I made my way |

kozo no shiori no |

|

into Yoshino— |

michi kaete |

|

I abandon now to visit |

mada minu kata no |

|

blossoms I have not yet seen. |

hana o tazunen |

Another poem by Son’an (Chūka jakuboku shishō, no. 188) presents us with a summer flower, the peony, and involves a similar claim that pits the poet against those of more conventional taste:

Behind a small house, a new bloom: shaped like jewels of ice.

I wonder: did rain wash the rouge away?

In the grand houses, they compete in reds and purples;

but this kind of elegance—this they know nothing of.

Appreciation of flowers from which the vivid colors have been washed away, the poet suggests, is something denied to those wealthy enough to get whatever they want.

ISHIKAWA JŌZAN 石川丈山, Shinpen fushōshū-a 260: About the Earthquake of the Summer of 1662

Word is, when the earth of the capital shook,

shopkeepers and nobles all dashed about in fear.

Mountains crumbled, the ground cracked, waters all around rose;

but the birds in the sky—they didn’t even know it happened.

CONTEXT: Like Kinoshita Chōshōshi, the samurai Ishikawa Jōzan (1538–1672) offended his patron and was forced into retirement at a young age. Before retiring to Higashiyama he was a scholar to the Asano clan in Aki Province. Rather than immediately withdrawing into seclusion, however, he studied Confucian thought and served in the retinue of a daimyo for a time, then retired to a cottage in the eastern hills of Kyoto and devoting himself to Chinese poetry. The earthquake of 1662—probably greater than seven on the Richter scale—struck the capital on the first day of the Fifth Month, when he was eighty years old.

COMMENT: Writing in Chinese allowed a poet to write about topics never contemplated in waka, such as the 1662 earthquake, which destroyed the Great Buddha at Hōkōji Temple and the stone bridge across the Kamo River at Gojō Avenue. Even in the mountains Jōzan must have felt the shaking, but it was in the crowded streets of the city below that the greatest damage took place; and the poem offers little concrete description of the event, instead employing only conventional phrases. The attitude is clinical rather than compassionate, the words of a distant observer. The last line suggests that as an old recluse Jōzan identified more with the birds flying above the fray than with the frantic crowds below. He was old and done with the worlds of status and commerce.

Another, more personal poem from his Shinpen fushōshū-b (The Fushō collection, revised edition, 1676, p. 178) was also written when Jōzan was living in his villa, the Shisendō, which he had adorned with the portraits of thirty-six Chinese poets he had commissioned from a member of the Kanō school.

Being Ill on a Summer Night

My body declines, my life nearing its end;

my heart is tranquil, but at night—no sleep.

The frogs croaking, the cuckoos calling—

in chorus with the rain, they blast my ailing pillow.

This poem does include seasonal icons and is closer to the waka tradition in feel. Even more so, however, its image of rain “blasting” the pillow where he lies ill reminds one of the Gozan poets. Chinese poetry in the Edo period embodied all such influences and was as important intellectually as court poetry, boasting a large number of practitioners and occupying an important place, especially among Confucian scholars but also among men of samurai birth.

OGYŪ SORAI 荻生徂徠, Soraishū (p. 202): Farmhouses on a Cove

The roadway follows the cove bank, winding along;

around the farmhouses here, fences are rare.

The banks are so low farmers can wash their tools;

when the skies are clear, it’s here people dry fishing clothes.

The little ox loaded with firewood stops to drink;

a small boat loads up harvested barley, then heads home.

Kids play in the sand on the shore;

the gulls are used to them and don’t fly away.

CONTEXT: Ogyū Sorai (1666–1728) was one of the premier Confucian scholars of his time. After retiring from government service in 1709, he established his own academy, where he led a “back to the classics” movement, meaning the Chinese classics and early Chinese kings. It was one of many schools at the time. His approach emphasized the need for law and authority but also personal cultivation rather than more openly political activities.

COMMENT: One of Sorai’s ideals, culled from the Chinese Book of Songs, was fūga, “courtly elegance,” a term that was also used by Matsuo Bashō. Sorai’s conception of fūga, however, focused more on the civilizing effects of poetry, meaning both that the content of poetry should be life affirming and positive and that the composition of poetry had an elevating effect on the poet. And his attitudes are apparent in the lifestyle he catalogues in the example here, from his personal collection, a regulated verse (lüshi) that presents us with a kind of investigation of things (“immediate manifestations of being”) that when properly perceived reveal the order behind the surface of sensory experience. The topic of “cove” (irie in Japanese) is common in waka: one remembers Shōtetsu’s use of the image in a stark winter setting, for instance. But Sorai’s poem concentrates not on the water so much as on people, who are noted as an absence in Shōtetsu’s conception but are very much present in Sorai’s. In this way Sorai suggests that the water is not only beautiful but also integral to the daily life of people: farmers, fisherfolk, ox herds and their oxen, harvesters, kids, and gulls, all of whom make brief appearances, making up a lively tableau. He mentions weather once (“when the skies are clear”), but only to represent the rhythm of life in such a place and to suggest that his description is not meant as a “sketch” of just one moment but rather a composite, as an idealized state of being presented in parallel sentences that represent order. Above all, what we see in his poem is labor and the utility of water, until we get to the children, who have achieved a kind of symbiosis with the gulls, symbolizing innocence and natural harmony.

In Sorai’s thought, achieving such harmony with the constantly changing realities of the natural world was the ultimate human goal. His view of human nature, while stressing the need for the kind of behavior inculcated by social and governmental institutions, allowed for personal engagement with important classical texts of the Confucian tradition and the development of individual talents. Predictably, his waterside scenes concentrate on the “lower” orders of civilized society, which he saw as providing the ultimate foundation for an orderly state.

GION NANKAI 祇園南海, Nankai Sensei shibunshū (p. 208): Expressing My Feelings

In my inn, the gloom of evening is beyond bearing;

wind blows frost-laden leaves as high as the second floor.

Thick-billed crows fly low in drizzle of dusky hue;

geese fly close as fulling sounds ring out in the autumn sky.

The season’s tokens are so right they surprise a traveler from afar;

with no hope of fame, I give myself to the floating life.

As to future plans—what will become of me?

Who will take pity on me, a boat unmoored?

CONTEXT: Gion Nankai (1677–1751) is considered one the finest painters in the Nanga style, a Japanese rendering of the so-called Southern School of Chinese painting (Nanzonghua). He was born into the family of a samurai-physician in Wakayama but from a young age was interested only in the arts. In his early twenties he committed an offense that put him in seclusion for a decade; thereafter, he worked as a Confucian scholar, dedicating himself to the life of a bunjin (literatus, connoisseur) and eschewing political affairs. Poetry, calligraphy, and music: these were his obsessions, which he sought to integrate into a lifestyle. Not surprisingly, he believed that the proper subject of all the arts was a realm of beauty and pleasure above the mundane world. The poets he most admired in the Chinese canon were Tang-dynasty masters such as Li Bai (701–762). He had little use for what he considered to be the overly rational poetry of the Song dynasty (960–1279).

COMMENT: This poem as taken from a modern edition of his works, Nankai Sensei shibunshū (Writings of Master Nankai), was written when Nankai was on the road and can easily be compared to famous waka on the ennui associated with the topic of travel. The setting is an inn; the season is late autumn or winter; the time of day, evening. In all, it is a monochromatic scene rendered with great artistry. The crow, considered an inelegant image in waka was not so in Chinese poetry; together with the wild geese, it draws our attention to the sky, as the sound of women fulling robes—an autumn task associated with lonely wives in traditional poetics—adds to the sense of gloom. All of this could of course be rendered in a painting, but the final lines of the poem shift our attention from the outer world with an “editorial” comment, noting that the landscape he sees is almost too perfect in terms of traditional motifs and ending with abstract statements that could not be expressed in pictorial form.

In the midst of this is the poet himself, a traveler and as such someone with no worldly ambitions, abandoning himself (taku su) to a floating life (rōyū), which is neatly symbolized by the unmoored boat, tossed on the waves. How much of the landscape was actually before Nankai’s eyes is impossible to say, although the phrase “the season’s tokens are so right” introduces a hint of reflexive play into his conception. The goal of painting and poetry in literati discourse was ultimately expressive rather than representational, and the scene Nankai presents is meant to convey his feelings rather than a realistic landscape. The title of his poem is a compound that appears frequently in waka and renga as well, where almost always we encounter not happy but melancholy thoughts.

KAN CHAZAN 菅茶山, Kōyō sekiyō sonshashi 117: First Day of the New Year

My two siblings are still alive,

and I have lived six of ten decades.

I still hope to meet with pleasures,

but life is a risk—what else can one say?

Ditches flow with muddy spring rains;

fields are thick with midday fog.

Once again I greet soft spring light;

birds join in with drinking songs.

CONTEXT: Kan Chazan is the sobriquet of the Confucian scholar Suganami Tokinori (1748–1827). He was born in Bingo Province (modern Hiroshima Prefecture) and after studying in Kyoto and Osaka spent much of his life there. Among his friends were Yosa Buson and other literati figures. He was sixty-one years old when he wrote this lüshi and was no doubt feeling his age, although he would live on for two more decades. His Confucian academy (which he dubbed the Village School of Yellow Leaves and Evening Light [Kōyō Sekiyō Sonsha]—the source of the title of his personal collection of 1812) in Kannabe, Bingo Province, was thriving. Twelve years before, he had turned over the family business, a sake brewery, to his brother so that he could dedicate himself to his scholarship, teaching, and, of course, poetry.

COMMENT: Chazan’s poetry is known for its gently subjective tone and focus on everyday life, including words and images sometimes regarded as too common and vulgar for “upright” and properly Confucian poetry. His setting in this case is New Year’s Day, which came in what is late January or early February in the modern calendar. It was the holiday of all holidays across all segments of society. Although often the weather did not show any sign of it, New Year’s was figured as the beginning of spring and treated as a time of renewal with family gatherings and trips to shrines and temples.

Chazan’s poem begins with sober reflection. He has been fortunate, he tells us: he and his sisters (named Chiyo and Matsu, records inform us) are still living; and he still anticipates experiencing joys (“enjoyable things,” which implies everyday, including ordinary, things, wine, women, and song, rather than more idealistic forms of happiness). But he is quick to add that life is uncertain. The word he uses is fusei, literally a “floating life.” In that sense his poem is only cautiously optimistic. The spring rains, which signal the end of winter cold and the advent of a season of rebirth, are not presented in the usual propitious terms: we see ditches of muddy water and fields thick with fog. If we feel a sense of new life in the scene, then, we realize that the perspective is more that of a farmer than of a traditional court poet, a landscape rendered in rustic terms and not as an elegant tableau designed to more explicitly symbolize notions of peace and order. And in his last lines we see the same thing: while acknowledging the soft light of spring, Chazan mixes the songs of drunks with birdsong. Thus in every respect the poem is earthy by comparison with standard waka, resisting the traditional associations of old aesthetic ideals.

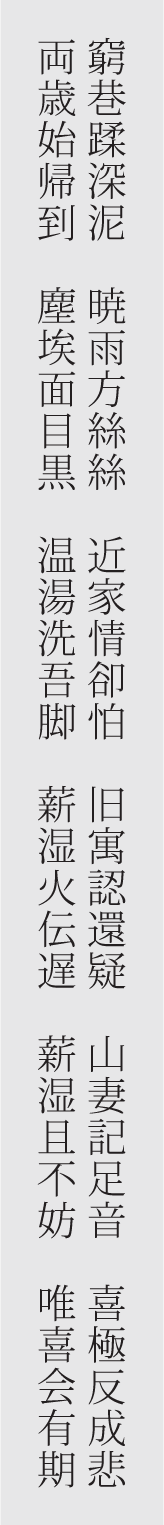

RAI SAN’YŌ 頼山陽, San’yō shishō 96: Arriving Home

On a backstreet, I trudge through mud,

amidst tendrils of dawn rain.

Approaching home, I feel uneasy;

spying my house, I feel even more unsure.

I hear my wife’s footsteps, a country girl’s steps,

and feel such joy that I become sad.

For two years I have not returned home;

my face is yellowed and dark from the world’s dust.

She makes to heat water and wash my feet,

but the firewood is damp, and the fire won’t start.

But damp firewood—that’s no bother;

I’m just glad to be with her again.

CONTEXT: Rai San’yō (1780–1832) was a Confucian scholar born in Aki Province (Hiroshima). He studied under his own father, also a scholar, and then other scholars, including Kan Chazan. In addition to Chinese poetry, he also wrote an important history of Japan. His stubborn behavior led to house arrest for three years and later disinheritance. By 1811, however, after turning down Kan Chazan’s offer to adopt him as his heir, he had a school of his own in Kyoto. In 1815, he moved with his family into a house near the intersection of Nijō Avenue and Takakura Street in Kyoto, but he often traveled. The poem here was written after a long absence.

COMMENT: This poem from San’yō’s personal collection of Chinese poems, published in the year of his death, presents a very personal story. After two years, the speaker—San’yō himself, there can be no doubt—is nervous about returning home; and the closer he comes, he tells us, the more unsettled are his emotions. His wife may resent having to raise children and manage a household without his support. Perhaps he wonders if she will have aged, or is concerned about what she will make of him—or both. The “world’s dust” (jin’ai) comes up frequently in Chinese poetry as a symbol of the filthy nature of the worlds of politics and commerce, in particular. San’yō says, graphically, that that dust has soiled his face.

The speaker characterizes his wife with one word, sansai—literally, a “mountain wife”—implying a contrast between the different worlds they live in, his intellectual, hers domestic. But then the tension dissolves as she plays her “proper” wifely role and prepares to wash the dust of the roads from his feet. Whether this is done lovingly or not is something we are not told, but it would be hard to think of it as anything but a moment of intimacy: a simple act of physical contact that would allow the ice to start breaking. And the final lines express relief. When the fire won’t start, the two people have a quiet time together, probably in silence—and just as well. He can savor a moment of physical relief, pay a little attention to his wife, and admit to himself that he is happy for domestic joys that he has all but forgotten.