5 A CULTURE OF CONSOLATION: MUSIC HALL AND MUSICAL THEATRE

In 1909 Europe seemed to be sleepwalking towards disaster. A music-hall hit of that year claimed ‘There’ll Be No War as Long as There’s a King Like Old King Edward’ (because ‘he ’ates that kind of thing!’), but unfortunately for all concerned, King Edward died in 1911.

In the US, popular music continued to grow and develop in a peaceful world. The country’s immediate pre-war music scene was quite different to Britain’s and wasn’t about to be frozen solid for four years. America was ushering in new names, new voices and new styles that would seem even more important in Europe after the war. Its songs were now being mass-produced.

Britain’s Edwardian age had been separated from its Victorian era by technology. In 1901 Marconi had sent a radio signal across the Atlantic; in 1904 came the first purpose-built cinema; and in 1906 the extended Bakerloo and Piccadilly lines were able to transport the working classes from Lambeth and Elephant and Castle to the more moneyed environs of Oxford Street and Regent’s Park in minutes. This new mobility – along with the football boom, the decline in religious observance, Electric Theatres showing ‘moving pictures’, and even the first roller-skating craze – were all meaningful strides away from tight British class strictures. The ermine-clad music-hall singer Vesta Victoria stuck it to lower-middle-class snobbery in 1907 on her recording of ‘Poor John’, where she found herself slowly being taken apart by a prospective mother-in-law, until the final verse: ‘She gave a sigh and cried, “I wonder what on earth he wants to marry for?” That was quite enough, up my temper flew. Says I, “Perhaps it’s so that he can get away from you.”’

Poor John’s mother would almost certainly have gone to see the Gaiety musical play The Merry Widow, brought to London by George Edwardes in 1907, in which the Austro-Hungarian bandleader Franz Lehár depicted a colourful Paris and an impoverished Balkan state in the 1860s. It was a huge hit. Edward VII came to one of the first performances, which made it a must-see. But it says a lot about recorded music’s lack of popularity in Britain in 1907 – partly because of the limitations of the two-minute cylinder or shellac format – that no English-language version was made at the time, and there wouldn’t be one until 1942. Sheet music and pianos were still a better outlet for home reproduction of musical theatre.

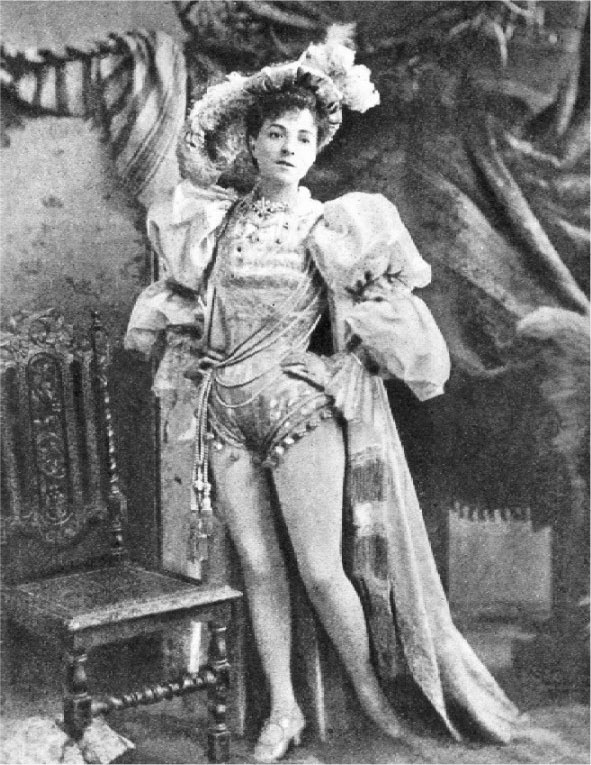

The Merry Widow’s star, Lily Elsie, was earning £10 a week from the show, but music-hall chorus girls were more likely to be on 35 shillings, even though the halls were more popular than ever. Grand London venues like the Empire Leicester Square, the Hippodrome and the Palace Theatre at Cambridge Circus – within yards of each other – were all late-Victorian, purpose-built music halls; they were also the work of architect Frank Matcham, who was keen on grand refinements, like the Indian-style interior and pagoda domes he added to the Empire Palace, Nottingham. Not to be outdone by Matcham, the Moss–Thornton group had cupids painted on the ceiling of their Liverpool Empire. These halls were now called ‘variety theatres’, the ‘t’-word distinguishing them from the older halls, which had been as much dining rooms and beer halls as places for entertainment.

Music hall had always been thought of as coarse and vulgar (which of course it often was), and had been battling against the moralists from the get-go. Yet, perversely, some of music hall’s strongest supporters were the ones trying to curtail its grubby charms. The Coliseum on St Martin’s Lane was built in 1903 by Oswald Stoll, a Liverpudlian impresario who was ashamed of music hall’s honest vulgarity and planned to improve it, clean it up, bring in some of the folks going to see The Merry Widow by making music hall a wholesome family entertainment – everything it hadn’t been. Signs appeared backstage: ‘Please do not use any strong language’ and ‘Gentlemen of the chorus are not allowed to take their whips to the dressing rooms’. In other words, said Stoll, mind your manners.

In 1906 came a new bill that recognised a worker’s right to withhold their labour. The music-hall strike began almost immediately, in January 1907. The strikers’ demands seemed quite reasonable: ‘No artist can be transferred from one theatre without artist’s consent’; ‘Times shall not be varied without artist’s consent’; and ‘No bias to be shown against any artist who has taken part in this movement’. Oswald Stoll led opposition to the strike, while Marie Lloyd stood by the striking performers. Stoll dismissed her ‘utterances’ as being down to her ‘innate partiality for dramatic effect’. Twenty-two halls were picketed, and the strike lasted until June, when it was ended by arbitration in favour of the artists.

Stoll needn’t have fretted so. What his fellow sensitive Edwardians had begun, new distractions for the working classes – the growth of spectator sport, the cinema, World War I and the advent of radio – all helped to finish.I By 1933 the Garrick was staging an evening of ‘Old Time Music Hall’; within thirty years of the Coliseum being built, music hall was essentially a thing of the past.

When the halls became a political battleground, the combative atmosphere put off many aspiring new acts, preventing fresh blood from joining the ranks. Ten-year-old Bud Flanagan was a budding conjuror but quit his music-hall gig as Fargo the Boy Wizard to go to sea as a ship’s electrician in 1910.II

The strike didn’t kill music hall; it just weakened its previously unassailable position. In 1909 Harry Champion brought the house down at the Metropolitan Theatre on Edgware Road with ‘Boiled Beef and Carrots’: ‘Don’t live like vegetarians on food they give to parrots. Blow out your kite from morn ’til night on boiled beef and carrots!’ (Champion also sang ‘A Little Bit of Cucumber’ to appease vegetarians.) 1912 saw the first Royal Command Performance at the Palace Theatre, London. Irving Berlin’s ‘Everybody’s Doin’ It’ was taken off the bill at the last minute, which must have pleased the rag-phobic George Robey. ‘The Palace girls danced charmingly,’ he recalled. ‘They actually dared to wear knee length skirts. I was surprised… some of my normally boisterous colleagues suffered at the hands of the censor who went through it with a fine comb.’ Robey sang alongside Harry Lauder and most of the music-hall greats, with the notable exception of Marie Lloyd. It was a respectable but very dull affair without her. Music hall hadn’t necessarily become more serious – Harry Champion’s ‘Any Old Iron’ (‘You look dapper from your napper to your feet!’) had been a hit in 1911 – but bawdiness was almost entirely eliminated. With the royal assent, music hall was now officially respectable, and its new status would be ridiculed in Wilkie Bard’s ‘I Want to Sing in Opera’: ‘I simply love Wagner, Mozart, Puccini, their music is really tip-top. So I mean to change my name Bloggs to Bloggini and see if I can’t get a shop… Signor Caruso told me to do so.’

The slow demise of music hall would also see the end of a potent weapon in the social struggle. ‘Boiled Beef and Carrots’ may have sounded boisterous enough, but songs about food – and the scarcity of it – were a reflection of working-class life that would never really be replaced. In 1901 J. A. Hobson had written: ‘Among large sections of the labouring classes, the music hall is a more potent educator than the church, or the school, or the press. The glorification of brute force and an ignorant contempt for foreigners are ever-present factors, which at great political crises make the music hall a serviceable engine for generating military passion. The art of the music hall is the only popular art of the day. Its songs pass quickly from the Empire and the Alhambra across the country, through a thousand provincial halls, clubs and saloons, until the remotest village is familiar with its songs and the sentiments.’

Given their often very localised material, the stars of the halls were surprisingly popular in America. The songs could just as easily set off the tears of America’s homesick immigrants, whatever their country of origin. 1905 saw thirty-five-year-old ex-miner Harry Lauder become a star with ‘I Love a Lassie’, a song he had written for a pantomime at the Theatre Royal, Glasgow; by 1908 he was doing a private performance for Edward VII at Sandringham. Lauder had been working as a music-hall performer in Scotland and the north of England, mostly as a comedian, but became an international star when he decided to tone down his accent, drop the jokes that were dialect-dependent and appear on stage fully kitted out in kilt, sporran and tam-o’-shanter. This must have been a weird throwback for someone who had worked for a decade down the mines of Hamilton, Lanarkshire, starting when he was fourteen years old, but it was a look that seemed to fit his own stirring, romanticised, Scottish-esque songs: not only ‘I Love a Lassie’, but also ‘Roamin’ in the Gloamin’’ and, most memorable of all, ‘Keep Right on to the End of the Road’ (written in 1916, a few days after his son had been killed in action).

Songwriter Irving Caesar’s family had arrived in New York from Romania in the 1890s. ‘Harry Lauder wasn’t loud, but he was a volcano,’ Caesar recalled. ‘My father had only been in this country ten or fifteen years. If he could go to a Harry Lauder presentation and come away and buy the records, and make the records part of their cultural experience, that proves something, doesn’t it?’

Caesar was one of a rising tide of American songwriters whose work would eventually eclipse Austro-Hungarian operettas and British music hall, but for now the US wept to ‘I Love a Lassie’ and swooned to the decidedly non-American, Viennese sounds of Franz Lehár, Emmerich Kálmán (The Countess Maritza) and Oscar Straus (The Chocolate Soldier). These were the descendants of Offenbach, but this was operetta largely without the raised eyebrow, romantic rather than witty. Gypsies seemed to be their major lyrical preoccupation. Lehár’s The Merry Widow wowed New York as it had London. A phenomenon at the time, its charms are largely untranslatable – like the Goons or Frampton Comes Alive! – to modern ears.

The Merry Widow had opened at George Edwardes’s Gaiety Theatre in 1907 and ran for more than two years. The Gaiety shows often made stars of their actresses, all of whom had hour-glass figures and milk-white skin, and The Merry Widow made Lily Elsie a huge star. Edwardes had originally signed up Mitzi Gunther, the original Merry Widow, who had made the operetta a hit in Germany and Austria, before he had met her; when she arrived in London, he got a shock and declared, ‘She has the voice of an angel, but no waist.’ The reality of weighty Teutonic operetta wasn’t for Edwardes, so he commissioned librettist Basil Hood to lighten the load and make The Merry Widow gayer and younger. The script now included the Ruritanian ambassador in Paris, Baron Popoff, and his troublesome pet, Hetty the hen. Lehár, a serious man, was unimpressed. Actor Joe Coyne, playing Prince Danilo, was such a lousy singer that he recited every song. When Lehár turned up to rehearsals, Edwardes convinced him that Coyne was ‘saving his voice’. None of this mattered. Lily Elsie became one of the most famous women in the country, and soon her face featured on chocolate boxes and biscuit tins. Middle-class women wore her wide-brimmed hat, and the ‘Merry Widow Waltz’ – reversed, in the Viennese style – was a sensation, selling over two million sheet-music copies.

The actresses in Edwardes’s shows were maybe the closest thing Britain had to pop stars. Appearing in Havana, Hope Hillier remembered meeting her co-star Gladys Cooper for the first time: ‘She came into the dressing room looking so beautiful that I had to gasp for breath.’ Stage-door johnnies had to be kept at bay, and Edwardes always felt slighted when his actresses married. Ruby Miller, with her spectacular red hair, became a favourite of the ‘mashers’ – Miller recalled them as ‘resplendent young men in their tails, their opera hat and cloak lined with satin, carrying tall ebony canes with gold knobs and gardenias in their buttonholes’. Max Beerbohm was a regular at both the Gaiety and Edwardes’s second theatre, Daly’s, and wrote about the allure and ‘surpassing joy’ of the actresses: ‘The look of total surprise that overspreads the faces of these ladies whenever they saunter onto the stage and behold us for the first time, making us feel that we have taken rather a liberty in being there: the faintly cordial look that appears for a fraction of an instant… the splendid nonchalance, all so proud, so fatigued, all seeming to wonder why they were born, and born to be so beautiful.’

In 1908 George Bernard Shaw’s sister Lucy returned from Germany and contacted Edwardes to tell him that Oscar Straus had turned Shaw’s Arms and the Man into an operetta called The Chocolate Soldier, and it was doing very well. The cocky Edwardes turned it down flat as Shaw had been sniffy about the Gaiety shows before, when he had been drama critic for the Saturday Review. His pettiness caused him to miss out on a huge hit – almost on the scale of The Merry Widow – and The Chocolate Soldier went straight to Broadway instead.

Edwardes opened a third theatre, the Adelphi, in 1911, but he was stretching himself and overestimating the lasting appeal of his style of poperetta. The Count of Luxembourg premiered there with great fanfare. Lily Elsie – now on £100 a week – was its star, Franz Lehár conducted, and King George V and Queen Mary were in the royal box on opening night. The Daily Chronicle wrote that Elsie gave ‘the strange impression of being from another world, where stage romances are life-and-death affairs, and a touch of the fingertips, a glance, a whisper, are matters of almost religious ecstasy’. Unfortunately, the paper also noted that ‘it is delicious while it lasts, but one comes away with few definite musical memories’. The Count of Luxembourg did poor business; the craze for waltzes was fading. And in worse news for Edwardes, Lily Elsie told him that she was to marry and retire from the stage. Soon after, he suffered a stroke from which he never fully recovered.

Changing musical tastes, ailing theatrical impresarios and the shadow of imminent war aside, the bioscope – or cinema, as it was soon to be known – was poised to replace the physical space of the variety theatre. Silent films threatened the musical play, so Edwardes came up with The Girl on the Film, a crude parody, in 1913. But a bigger threat came from the ‘revue’, an American import which didn’t have a need for a plot, just sketches, solo turns, songs and dances linked together by a vague central theme. Albert De Courville, a reporter for London’s Evening News, travelled to the US to study the way Americans produced their shows; he returned full of ragged-up enthusiasm and booked the Hippodrome to stage Hullo Ragtime in 1912. He brought a ‘trap’ drummer, cornet player and trombonist over to join the Hippodrome’s own orchestra. Its leader, Julian Jones, initially loathed this intrusion – ‘This is not music,’ he told De Courville, ‘it’s against all the principles of music!’ – but when the non-stop show was a runaway hit, he eventually conceded it was ‘quite effective’. De Courville allowed for no curtain waits and brought in an American dance instructor who drilled the chorus girls in a manner that was alien to Edwardes’s delicately staged routines. Everything about Hullo Ragtime moved faster, faster.

The difference in the pace of Edwardian Britain and America could be summed up by the story of James Bland, a black middle-class New Yorker.

Genuine black minstrel troupes – known as Georgia Minstrels rather than Nigger Minstrels, who were in blackface – had been popular in Britain since the 1870s, in the halls as well as when performing for nobility (Queen Victoria was alleged to have cracked a smile for one Billy Kersands of the Hague and Hicks troupe). Bland arrived in London in 1882, with his five-string banjo, as part of the Haverly troupe. He was quickly acclaimed for his own compositions: ‘Oh Dem Golden Slippers’, ‘Hand Me Down My Walking Cane’, ‘Carry Me Back to Old Virginny’ (‘where the cotton and corn and taters grow’) and the sweet barbershop harmonies of ‘In the Evening by the Moonlight’. The pre-war South in all its mythic honeysuckle gentility was evoked by Bland’s songs, and Britain hailed him as a successor to Stephen Foster, slapped his back, bought him drinks and treated him with due respect. When it was time for the Haverly Minstrels to go home, Bland decided to stay on in London.

His billing was ‘James Bland – the Idol of the Halls’, and he began to sing songs about London life while dressed immaculately in a suit. English hospitality began to catch up with him, though, and his fondness for pubs led him to turn up late for shows and stumble over his words, which his hosts put down to southern eccentricity. Yet when he returned to New York at the turn of the century, his homeland saw him as yesterday’s man, washed up. Ragtime was taking over, and his songs seemed old-fashioned, embarrassing, an echo of a past that newly urbanised America – especially black America – was keen to forget. Bland died, broke, in 1911.

In the shadow of a war that some knew was coming, Britain felt like it was in a state of flux. In stark contrast to the metallic brashness of Sophie Tucker and ‘Oh You Beautiful Doll’, the pre-war gentility of Britain was summed up by one of 1912’s biggest hits, Sidney Baines’s ‘Destiny Waltz’. A piece of light music that led to a series of Baines waltzes – ‘Ecstasy’, ‘Mystery’, ‘Victory’, ‘Witchery’ and the language-mangling ‘Frivolry’ – it sold a million copies and couldn’t have been more date-stamped; it was allegedly one of the tunes played on the Titanic. The light classical sound of the English tea dance, as much as the newly tamed world of music hall, met its nemesis in ragtime. J. B. Priestley saw the revolution at close quarters: ‘Of all the new exciting things that were crowding into our lives, the most urgent hit me when I went over to Leeds to a variety show at the Empire and heard Ragtime. Suddenly, I discovered the 20th century, glaring and screaming at me. The syncopated frenzy of this was something quite new – shining with sweat, the ragtimers almost hung over the footlights, defying us to resist the rhythm, drumming us into another kind of life in which anything might happen.’

Sophie Tucker was the physical embodiment of emancipation, and her American voice was the sound of Britain’s near future. In 1913 she began calling herself the ‘Mary Garden of Ragtime’ (Garden being a contemporary Scottish opera singer); she would have the pop nous to switch her nickname after the war to ‘The Queen of Jazz’ and picked up a new backing band called the Five Kings of Syncopation. Britain in 1913 was whistling a new music-hall song that still retains a sadness almost too great to think about. Florrie Forde recorded ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’ as a lament from an Irish worker in London; a year later, it signified a far greater homesickness.

- I. The same new pastimes meant that choral societies and brass bands – staples of the Victorian age – went into decline. In 1910 The British Bandsman’s Yorkshire correspondent asked, ‘Can anyone account for the apathy of the younger generation against becoming bandsmen?’ One answer was to be found in the centre of Bradford a year later, when Bradford City paraded the FA Cup for the first and only time, and ‘the multitude surged and swayed in Town Hall Square, Forster Square and Peel Square… a solid mass of people some of whom swarmed up lampposts in order to catch a glimpse of the Cup. The cheering swept through the streets in waves, and the teeming populace seemed almost frantic with joy.’

- II. Ironically, Bud Flanagan, with partner Chesney Allen, would later became one of the last hold-outs of music hall. A gentle singing comedy duo, they didn’t work together until the mid-1920s, but had become beloved stars of the Palladium by the end of the ’30s. Their sound was somehow very comforting, with Flanagan singing and Allen vaguely harmonising in a semi-spoken voice. Flanagan’s own ‘Underneath the Arches’ became their signature tune.