28 BE LIKE THE KETTLE AND SING: BRITAIN AT WAR

In 1941 there were at least 50 clubs in Soho, probably more – bottle clubs where you were supposed to order drinks in advance – nobody obeyed the law. I worked in a first floor club all through the air raids, no stopping for bombs. People were fatalistic but tremendously happy. Everybody had the feeling that death was on the doorstep, so they all had a good time. As I walked back to Aldgate at 3 or 4 in the morning the whole of the City of London would be alight. We walked on through it almost every night, bomb stories were two a penny. It wasn’t bravery, there was nothing you could do about it – it just went on night after night.

Tony Crombie, jazz drummer

When World War II was declared on 1 September 1939, the BBC made a decision to cut all music – whether pop, light or serious – from its schedule. It badly misjudged the national mood. Over the next six years, entertainment – especially popular music – would come very close behind food and shelter in the list of needs of a nation at war. Vera Lynn would sing directly to the troops – ‘The London I Love’, ‘It Always Rains Before the Rainbow’ and ‘The White Cliffs of Dover’ – and receive a thousand letters a week that were more like thank-you notes than fan mail. The BBC’s stance led to a sudden boom in record sales in 1939, as people still wanted and needed to hear Joe Loss’s ‘Let the People Sing’ (‘any sort of song they choose, anything to kill the blues’), with its odd blend of church-bell brass, maudlin middle-European violin and a chorus message that seemed to be aimed directly at the BBC.

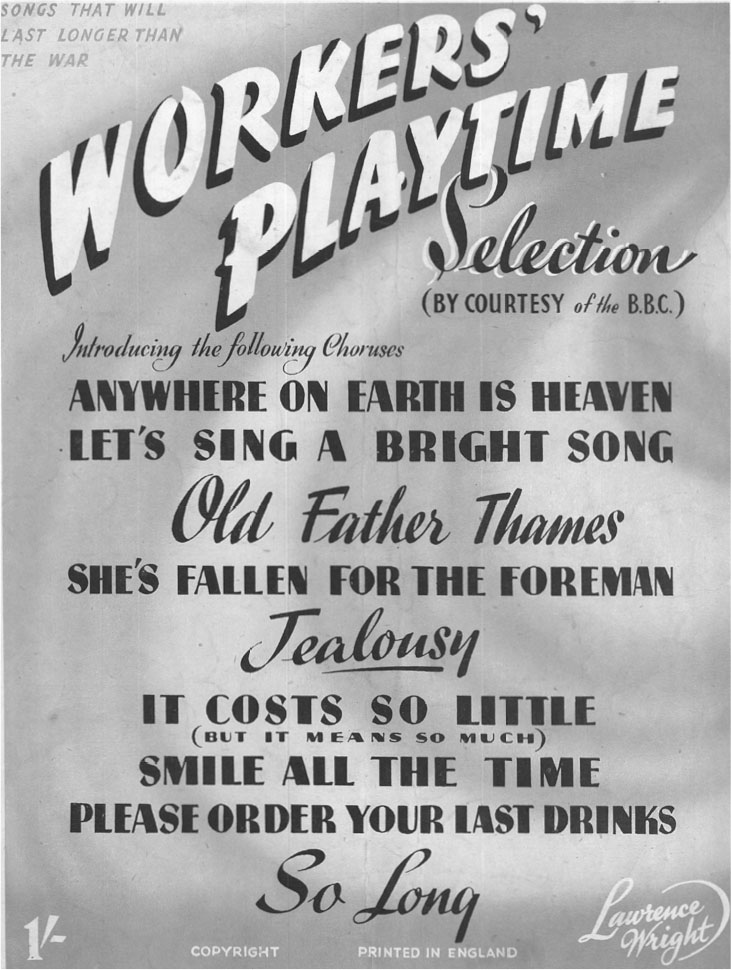

War or not, people in Britain still liked to get drunk and sing. By the end of 1939 half a million sheet-music copies of ‘Beer Barrel Polka’ had been sold in Britain, and it mutated into ‘Roll Out the Barrel’, the country’s most popular singalong, with the possible exceptions of ‘The Hokey Cokey’ and ‘Happy Birthday’. The BBC, facing a storm of criticism (‘The most pitiful exhibition of complacent amateurishness to be heard on the whole of this planet during the first weeks of war,’ roared Gramophone’s Compton Mackenzie), relented, setting up a ‘slush committee’ to decide what to broadcast.I Cecil Madden, a BBC programmer, recalled, ‘Every week we had to go through mountains of songs and records. We existed to ban songs, which was very unfortunate, because one likes to be creative.’ To sum up its new role, BBC producer Wynford Reynolds coined the phrase ‘victory through harmony’. The Corporation began to broadcast from factories and military camps. Sometimes young non-combatants, like child stars, would drop in. Even regular Joes would get to sing on a show called Private Smith Entertains.

The Harry Roy Band’s tribute to ‘a stately gentleman we love so’, ‘God Bless You, Mr Chamberlain’, was a big hit during the ‘phoney war’ in 1939: ‘You look swell holding your umbrella, all the world loves this wonderful fella.’ But as the years rolled on, with no real light on the horizon, Vera Lynn’s ‘We’ll Meet Again’ would become the melancholic anthem: ‘don’t know where, don’t know when’. When bombs started falling, the BBC had to acknowledge popular music’s power and the nation’s shared affinities, and, to be fair, it did. The phoney war ended abruptly on 7 September 1940 – Black Saturday – when 430 people were killed in London and a further 1,600 were injured. The city was then bombed for fifty-seven consecutive nights.

Vera Lynn came from the halls and variety theatres, and she rose to fame thanks to the long run of Apple Sauce at the London Palladium, in which she starred with comedian Max Miller. But Vera was made for radio and would go on to become as associated with World War II as Churchill. Quite long-faced and rather toothy, she wasn’t Betty Grable, but her voice was perfect for the job in hand; her songs projected the values of home and family, and her heartfelt, slightly melancholic voice conveyed a powerful imagery over the airwaves. The Radio Times noted that by the spring of 1941 her blend of girl-next-door glamour and reassurance had made her the number-one ‘sweetheart of the forces’, and by the end of the year, with Sincerely Yours, Lynn was on the air. Covering a lot of ground, she had to act as lover (‘Yours’), lucky talisman (‘We’ll Meet Again’), mother (the lullaby ‘Baby Mine’ from Dumbo) and seer (‘White Cliffs of Dover’). She turned longing and absence into a communal experience. Still, it wasn’t enough for the BBC: Basil Nicholls, controller of programmes, said ‘the programme is solidly popular with the ordinary rank and file of the Forces. On the other hand, it does not do us any good to have a reputation for flabby amusement.’ And so even Lynn’s position was constantly under review. At one point she was off the air for a year, only returning in 1944, with Thirty Minutes of Music in the Vera Lynn Manner. But then it was quite un-BBC that a working-class Londoner who refined her accent only moderately for broadcast represented the unity of the nation.

Having decided that popular music was good for morale (a decision it would still rescind at various points in the war), in late 1939 the BBC broadcast a variety concert from RAF Hendon, where Mantovani’s orchestra played ‘We’re Going to Hang Out the Washing on the Siegfried Line’, with a vocal refrain from Adelaide Hall, the Cotton Club legend. She had just arrived in London from Paris; with help from bandleader Joe Loss, she found herself in the BBC’s employ within a matter of days.

Hall’s contract with the BBC, and her theatre shows around the country, contrasted sharply with her Cotton Club days, when the colour divide between stage and audience had been absolute. Still, Britain had its own race issues to deal with. In 1932 the Paramount Ballroom on Tottenham Court Road opened underneath the huge art deco Paramount Court apartment block. It was black-run and welcomed an almost exclusively black crowd; a few white girls might have braved the dirty looks, but certainly you never saw white men. This was somewhere to come at the weekend to meet other people of your own skin colour, listen to West Indian musicians and relax without anyone giving you trouble. At the end of the night the banquettes were often occupied by people who couldn’t find a home in their often unwelcoming host country. Britain didn’t have a colour bar, but there were plenty of problems, and housing was already a serious issue for Caribbean émigrés.

Habitués of the Paramount would have struggled to find genuine swing on the radio, but for thirty minutes every week the BBC provided an alternative to the soma-like Music While You Work. Broadcasting a solid half-hour of swing every week, Radio Rhythm Club began in June 1940. Record collecting played a vital role in British jazz fandom. Almost no one heard swing in the flesh, unless it was a token number played by a British dance band; everyone’s accrued knowledge came from records. This led Radio Rhythm Club to have a scholarly tone – catalogue numbers would have been mentioned frequently – and it was, unsurprisingly, male-dominated. Out of 211 broadcasts, only two featured women as announcers or guests. Mary Lytton and Bettie Edwards wrote together under the gender-free name B. M. Lytton-Edwards for Swing Magazine and were just as likely to make references to catalogue numbers as the guys. They also had a glamorous/not-glamorous back story, pretending to have grown up on a farm in Iowa, where they were subjected to ‘Sweet Adeline’ endlessly, before hot jazz saved their souls. Gender balance aside, Radio Rhythm Club was popular with the fans. It was presented by Charles Chilton, a genuine jazz enthusiast who was not only hip enough to describe something hot on Savoy as ‘the last word’, but also had a very non-BBC, relatable London accent.

The show even had space for jitterbug-friendly jam sessions with Harry Parry’s Radio Rhythm Club Sextet, a decent outfit led by the Goodman-influenced Parry that featured black British guitarist Joe Deniz, drummer Bobby Midgley, ‘vibraphone ace’ Roy Marsh and future superstar pianist George Shearing. They caused a near-riot when they played in Deniz’s home town of Cardiff, and one lad who enthusiastically jumped on stage had to be wrapped up in a curtain and carried off by stagehands.

A rare out-and-out British jazz bandleader, Parry had started out in Llandudno and had been playing at Mayfair’s St Regis restaurant – the group was called the St Regis Quintet at this point – before the BBC called. The sextet’s records on Parlophone are a delight (especially their ace signature tune, the Parry-written ‘Champagne’), and their popularity led to the over-subscribed Cavendish Swing Concert, a public jam session that spun off from Radio Rhythm Club in January 1942. ‘Swing fervour reached a new high level in this country… when 2,500 eager, enthusiastic, foot-stomping and wildly applauding fans packed the London Coliseum to capacity,’ wrote Melody Maker. Back in 1941 the paper had been rather less excitable: ‘The BBC Rhythm Club is the final and ultimate gesture, a sort of non-aggression pact between swing and officialdom, and everybody is happy.’ By 1945 the scene had grown so much, thanks to Harry Parry and Charles Chilton, that small-group swing programming at the BBC – from combos led by Frank Weir, Johnny Claes and Stéphane Grappelli, as well as Parry – had become almost commonplace.

The Squadronaires were formed as a ‘service dance band’, with a nucleus of players from the Ambrose band. They pilfered swing arrangements from Bob Crosby and made a British wartime hit out of his ‘South Rampart Street Parade’. George Chisholm had been Bert Ambrose’s trombonist and remembered how half a dozen band members ‘decided to volunteer in the RAF, not through bravery, I’m sure. Six of us went up like idiots and said, “Here we are, we’re a band.” We went to Uxbridge, a parent station for a few weeks, sweeping floors, cleaning lavatories, and in the evenings we’d sit and have a little blow. It strayed into the office of the commanding officer, and he said, “Splendid, why don’t you play in the officers’ mess this Friday?” Consequently we were sent to Germany and France and Holland and what have you, and we joined the entertainments there.’

The Air Council objected most strongly to the name. They insisted the band was called His Majesty’s Royal Air Force Dance Orchestra, with the bossy credit ‘by permission of the Air Council’, on Decca 78s, such as 1941’s ominous, atmospheric, multi-part ‘There’s Something in the Air’. As time went by, the Air Council began to allow the use of ‘the Squadronaires’ in small print; the more the band played, the larger the print became.

This system – or lack of it – also created ‘supergroups’ the Skyrockets (officially known as the Number One Balloon Centre Dance Orchestra) and the Blue Rockets (the Royal Ordnance Army Corps Dance Orchestra) from the cream of Britain’s existing bands.II Ivy Benson’s outfit played alongside the Squadronaires and Skyrockets at the Jazz Jamboree of 1943, and it is worth dwelling on her band. Benson was one of the few women to lead an all-female band, along with Blanche ColemanIII and Gloria Gaye (whose band wore silver lamé dresses and were coached by Geraldo), though all three are barely remembered now. Ivy had been a regular performer on the BBC’s Children’s Hour, broadcast from Leeds, since she was nine, and worked in a factory until she could afford to buy her first alto saxophone and move to London. By the early 1940s she had become a bandleader herself, and her outfit landed an unofficial gig as a resident dance band at the BBC in 1943. She wanted to lead a group of female musicians ‘who not only looked good but sounded good’, and who worked hard too. Most of her players arrived from works’ brass bands in the north of England. Trumpet player Gracie Cole had won so many awards with bands in Yorkshire (the Grimethorpe Colliery Band, the Besses o’ th’ Barn brass band) that it took £18 a week to lure her down to London in 1945; she later joined the higher-profile Squadronaires. Holding on to musicians proved tricky: they were also magnets for GIs and frequently quit the band to get married. ‘I lost seven in one year to America,’ moaned Ivy. ‘Only the other week a girl slipped away from the stage. I thought she was going to the lavatory but she went off with a GI. Nobody’s seen her since.’

The fact that so many male musicians were away certainly furthered the cause of the Benson band, but they were still a constant target for sniping men; the Dance Band section of the Musicians’ Union even sent a delegation to Broadcasting House to vent their fury. ‘It was the plum job in the country. The reviews for the first broadcast were vitriolic,’ remembered Benson trombonist Sheila Tracy. Melody Maker labelled it ‘The Battle of the Saxes’. Ivy’s three hundred fan letters a week from servicemen suggested it was nothing more than jealousy and misogyny.

Still, men ultimately ran the show. At the personal request of Field Marshal Montgomery, the Benson band were flown to Berlin to play at a concert celebrating the end of the war. And with that, Britain decided that all-female bands had pretty much served their purpose. The men were back now. ‘Every door slammed in her [Benson’s] face,’ said Tracy. ‘Even the BBC turned their back on her. A committee of bandleaders was set up and they all closed ranks – with the band circuit booked up there was nowhere to go.’ After the war, the Ivy Benson band would be largely relegated to playing American army bases and Butlin’s holiday camps.

In the autumn of 1940, as the Blitz raged on and dance bands were decimated by the call-up, the BBC’s options were limited. It could call on all-female bands, but it was also within its remit to support the civilian dance-music profession during the war. With the Skyrockets and Squadronaires covering musicians in service, the BBC decided to offer Jack Payne’s and Geraldo’s outfits indefinite contracts as house bands. They were signed up to the Corporation’s Dance Band Scheme, which meant the band members would be exempted from the draft; each band would have a stable line-up and, therefore, some guarantee of quality players. To add a bit of variety, these two outfits would be supplemented on air by a ‘band of the week’, like Bert Ambrose’s or Billy Cotton’s.

For £250 a week, Payne committed to give three broadcasts for the Home Service and Forces Programme, plus a further three for the Overseas Service. Like a doctor, he agreed to be on call six days a week. As well as performing straight dance-band music, Payne’s eighteen-piece outfit had a show called Moods Modernistic, which could include light classical pieces like Massenet’s ‘Elegy’, as well as ballad hits of the day, like Billie Holiday’s ‘I Don’t Want to Cry Anymore’ (Bruce Trent, Payne’s male vocalist, handled this one). Melody Maker described Payne’s arrangements as ‘overdone’ and his brass section as ‘weak… Jack’s band never really swings a phrase, even by accident.’

Still, there was a reassuring familiarity to this heavy rotation of Payne and Geraldo, and besides, Geraldo had a certain slickness. One Columbia Records advert described him as ‘polished and streamlined… fastidious’. He didn’t attempt to cover up his north London accent and enjoyed tinkering with his life story. The one-time Gerald Bright had studied piano at the Royal Academy of Music and led hotel bands in Blackpool during the 1920s, before apparently heading to Brazil in 1929 to study coffee plantations. While there – and there’s no evidence he ever was – he became intrigued by the tango, and returned home to front the Gaucho Tango Orchestra, changing his name to Geraldo while he was at it and landing a residency at the Savoy in 1930. Melody Maker described his appearance as ‘polished to the last demi-semiquaver’. He was open to swing, though, sneaking things like ‘Stormy Weather’ and ‘Ain’t Misbehavin’’ into Tunes We Shall Never Forget, a BBC oldies show.

Geraldo spoke to the troops as well, who were turned off by Payne’s pomposity as much as his straight-backed arrangements. ‘I think the greatest kick I get out of my job these days is when we are broadcasting to you fellows,’ he told them. His style was intimate and informal. On top of this, he was a genuine swing enthusiast, and among his innovations was a swing septet, made up of existing band members, which played relatively daring material, like guitarist Ivor Mairants’s ‘Sea Food Squabble’ (1942).

Geraldo later reminisced on life during wartime with the jazz journalist and broadcaster Benny Green: ‘We used to start broadcasting and then the warning would go, air raid warning. And then we’d go onto short wave and still continue broadcasting. We couldn’t come out because there was an air raid going on outside, so we used to have mattresses on the floor at the bottom of the Paris cinema and try and sleep down there. When the all-clear went in the morning we’d get up, go back to our respective homes, have a shave and a bath, and come and start broadcasting again.’

Radio could reach nearly everybody, but live performances were also important. Geraldo played at factories around the country, where the reaction was ‘second to none, they absolutely lavished in it’.

The difference between British and American wartime music was encapsulated not by Payne or Geraldo, or even Radio Rhythm Club, but by the BBC’s Dancing Club, hosted by ‘strict-tempo’ ballroom phenomenon Victor Silvester. Aged fourteen, he had lied about his age to fight in World War I and unwillingly became part of a firing squad that shot fourteen deserters. A complete change of direction was necessary for his mental well-being, and it came after the war, when he attended a tea dance at Harrods. Realising his feet were his fortune, he then won the first-ever World Dancing Championships in 1922, and his book, Modern Ballroom Dancing, was a million-seller. By the late 1920s Silvester had his own dancing school in Bond Street, approved by the Imperial Society of Teachers of Dance. It was all about rules – slow, slow, quick, quick, slow – and to anyone outside of the ballroom scene, it was a form of dancing that seemed thoroughly joyless.

Silvester didn’t like much of the recorded music he heard and was peeved by unnecessary solos, silly vocal refrains and (most of all) drummers doing silly paradiddles. So in 1935 he picked up a baton and started to record ‘strict tempo’ records for Parlophone, metronomic but catchy things like Sammy Cahn and Jule Styne’s ‘And Then You Kissed Me’ and Joseph Meyer’s ‘You’re Dancing on My Heart’, which became his signature tune. In March 1941 the BBC Variety Department’s Mike Meehan called him up and said, ‘There are thousands of service men and girls at camps and gun sites miles from anywhere. It occurred to me that if you gave dance lessons on the air it would help them to pass the time.’

Silvester was there to help pass the time. His music was sensible. There were no vocals to interfere with the seamless glide of brushed drums, with just a piano and either a violin or clarinet as the cherry on top. No shocks or surprises at all – that was the point. Silvester was a tall, athletic man, a smoothie who started each Dancing Club broadcast with ten minutes of instruction; this appealed to both the BBC’s conservative side and the British weakness for being gently told exactly how to behave. The Radio Times would print diagrams to accompany each broadcast so that people could practise in their parlours, feet rotating like helicopter blades. Silvester’s band became the most popular in the land, and his regimented dancing became known (in Britain, at least) as the ‘international style’.

You would think he considered the music to be entirely secondary, if it wasn’t for a second band he started in 1943. Inspired by the influx of American GIs, he held the baton for a series of terrific recordings, under the name Victor Silvester’s Jive Band. The sound was far from the suave, slick hum the public might have expected. With arrangements by pianist Billy Munn and players like ace trombonist George Chisholm and Silvester loyalist ‘Poggy’ Pogson on sax and clarinet, 78s like ‘Crazy Rhythm’ and ‘There’s No Honey on the Moon’ sounded like jazz loyalists had finally been let loose at Abbey Road. Post-war, though, Silvester reverted to the minimal, tidy sound that had made his name, which earned him his own request show on the BBC World Service. By the time he died in 1978 he had sold some seventy-five million records.

If Vera Lynn was the forces sweetheart, Gracie Fields was everyone’s big sister. ‘Our Gracie’ was at the height of her fame at the outset of World War II. In 1939, having just been given a CBE for services to entertainment, as well as the Freedom of the Borough of Rochdale, she became seriously ill with cervical cancer. The public sent her over 250,000 goodwill messages. Knowing she had a job of morale-boosting on her hands, she cut ‘Old Soldiers Never Die’ and the upbeat ‘I’m Sending a Letter to Santa Claus’, the biggest Christmas hit of 1939. Best of the lot was ‘The Thingummybob (That’s Going to Win the War)’, which made mind-numbing manufacturing jobs seem a little less pointless. Then disaster struck. She fell in love with the Italian-born film director Monty Banks and married him in March 1940. Banks had been christened Mario Bianchi, across enemy lines, in Italy. As he remained an Italian citizen, he would have been interned in the UK, so the couple were forced to leave Britain for North America, and the public’s affections for Our Gracie became understandably muted. Once the conflict was over, though, Gracie was forgiven and welcomed home, and she scored her biggest-ever hit with the stately ‘Now Is the Hour’ in 1948.

With Our Gracie abroad, Petula Clark became like another family member, Britain’s daughter or kid sister. She toured the country with another child star called Julie Andrews, the two performing at the Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA) shows put on for troops at all the training camps, airfields and bases around London and beyond. Julie was a little buttoned-up, very proper, performing with her parents as ‘Ted and Barbara Andrews and their little girl Julie’. Petula, on the other hand, sang swing numbers, cracked jokes and did ‘When That Man Is Dead and Gone’. ‘The first show I did for the BBC was at the Criterion theatre on Piccadilly,’ she recalled, ‘which the BBC used because it was underground. It was full of sandbags; it was really “London in the war”. Our mum was Welsh, so when things really got a bit too hectic we used to go off to Wales, which I loved.’ She would travel from one camp to another in troop trains, never really knowing where she was, sleeping in the luggage rack. ‘And, of course, there were no lights. It was kind of strange.’ Still, she was a little envious of her fellow child star: ‘She sang with this amazing voice. I’d think, “How does she do that?”’ As it turned out, neither of them would need to worry about their future.

The majority of Britain’s wartime hits were still American in origin, but this feels like a good place to salute Northern Ireland-born Jimmy Kennedy. He had been a career civil servant in the early 1930s, and a lyricist on the side, but he wrote such unlikely hits as ‘The Teddy Bears’ Picnic’ (a Henry Hall hit in 1941). He had written the first indisputable classic of the war, ‘We’re Going to Hang Out the Washing on the Siegfried Line’, in 1939, when the war still seemed like an abstract concept. Kennedy had turned a chain of fortifications along Germany’s western border into something relatable to your back yard.

Kennedy would go on to write travelogue standards like Gene Autry’s Mexican tear-jerker ‘South of the Border’; ‘Isle of Capri’ (after he heard Gracie Fields gushing about her holiday home) and ‘April in Portugal’ (both of which Frank Sinatra went on to record); and ‘My Prayer’ and ‘Harbour Lights’ (which would give the Platters’ adult-oriented doo-wop hits in the mid-1950s). His best-known song might be ‘Red Sails in the Sunset’, cut by everyone from Bing Crosby to Fats Domino and written about his home town of Portstewart, in County Londonderry. Even though he never sought publicity, it seems bizarre that one of the most successful songwriters Northern Ireland has produced – only Van Morrison can really come close – remains so obscure. On the promenade in Portstewart, the local hero and his ‘Red Sails in the Sunset’ are commemorated by an abstract copper sculpture of a fish and a sail, once reddish, now green.

Arguably the most popular song with the British troops was of German origin. ‘Lilli Marlene’ (originally called ‘Song of a Young Sentry’) had been recorded in 1939 by Lale Andersen and picked up by the Axis-run Radio Belgrade, which played it at the same time every night. It had a bewitching effect. Soldiers on both sides tuned in to hear it, and soon different countries had their own recording. Anne Shelton, one of Jack Payne’s singers, recorded it with an English lyric by Tommie Connor, who had also written Gracie Fields’s more jovial ‘The Biggest Aspidistra in the World’ and Vera Lynn’s ‘Be Like the Kettle and Sing’. Shelton, still a teenager when the war ended, also recorded Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein III’s Academy Award-winning ‘The Last Time I Saw Paris’, but Tony Martin scored the bigger UK hit with this; the lyric’s familiarity with Parisian life somehow sounded more convincing coming from an American rather than an unworldly girl from Dulwich.IV Also written from a safe distance was Eric Maschwitz’s ‘A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square’, composed in 1939, while he was staying in Le Lavandou, in south-east France. It was placed in the London revue New Faces and sung by Vera Lynn, and would go on to become a standard.

On the home front, the war’s ultimate soundtrack would be Vera Lynn’s ‘The White Cliffs of Dover’, which had been written by New Yorkers Walter Kent and Nat Burton in 1941 to uplift the spirits of the British as the threat of a Nazi invasion seemed at its most imminent. Its American origins explain why bluebirds are included in the lyric, even though they’ve never been spotted in Dover during wartime or peacetime, but it was a beautiful gesture from one side of the Atlantic to the other. Vera sang it on the very first broadcast of Sincerely Yours in November 1941. A month later came Pearl Harbour.

- I. The slush committee would be wheeled out on a regular basis. In 1942 there was a ban on ‘numbers which are slushy in sentiment’; in 1943 they blacklisted crooners – ‘anaemic or debilitated performances by male singers’ – who might somehow emasculate our servicemen; and in the same year the Corporation decided to promote Britishness over ‘pseudo-American’ music, which left the swing-friendly house band of Geraldo out in the cold.

- II. The Squadronaires included saxophonist Cliff Townshend, father of the Who’s Pete Townshend. A clarinet player in the Blue Rockets was Edwin Astley, who went on to write TV themes for The Saint, The Champions, Department S and Danger Man in the 1960s.

- III. Andrew Motion reckons that Blanche Coleman was the inspiration for the pseudonym Brunette Coleman, under which Philip Larkin wrote risqué girls’ school stories, though Larkin hate figure Ornette Coleman seems just as likely.

- IV. Shelton’s career would survive well into the 1950s. She had a number-one hit with the Joe Meek-engineered ‘Lay Down Your Arms’ as late as 1956, the year of Suez, the Hungarian uprising and Gene Vincent’s ‘Be-Bop-a-Lula’.