The Velvet Revolution that magically began that afternoon was to produce a fundamental change of governmental power, without sparking civil war. Like all revolutions, it triggered bitter public controversies about who gets what, when, and how. It tore apart the old political ruling class and invented new rules for new political actors. The revolution bestowed the power to govern on new decision-makers. It forged new policies for tackling local and national problems and for reacting with and against international swings and trends. But the revolution did something more basic than this. It also flung everybody temporarily into an everyday world marked by flux, ambiguity, contingency. No doubt, the revolution drew together clumps of previously divided citizens who shared new memories, values, aspirations. The revolution legitimated not only governments and policies — practical outcomes — but also new shared sets of symbolic meanings and emotional commitments. The revolution produced a collective feeling of solidarity of the previously powerless. But in granting citizens a new freedom to speak and act differently the revolution also forced everybody into a state of unease. It catapulted them into a subjunctive mood. All of a sudden, some things were no longer sacred or forbidden. Everything seemed to be in perpetual motion. Reality seemed to lose its reality. Unreality abounded. There was difference, openness, and constant competition among various power groups to produce and to control the definition of reality.

When millions of oppressed people are flung together into a subjunctive mood they naturally feel sensations of joy. Hope and history are words that seem to rhyme. ‘Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,’ wrote Wordsworth, and so it usually is in all upheavals of a revolutionary kind. Revolution is a transformative experience. ‘It was like a step into an unknown space,’ said Havel, as if everybody was staging ‘a play that was unfinished’.302 Revolution is an adventure of the heart and soul. Citizens initially feel personally strengthened by it. Their inner feelings of barrenness, emptiness, isolation momentarily disappear. They lose their fear. They feel lighter, joyful, more enthusiastic, even passionate about their family, friends, neighbours, acquaintances, and fellow citizens. They feel they have a future. Astonished, they discover boundless energies within themselves. They experience joy in their determination to act and to change the world. Their participation in the turbulent thrill of the revolution becomes a giddy exploration of the unknown. The Germans call this giddiness Freude. The French call it jouissance. The Spanish call it alegria. The Czechs call this state of intoxication euforie.

All this is familiar. But it is equally clear that revolutions are also fickle events. Revolutions are times of condensed uncertainty. The joyful solidarity they produce is always countered by a shared sense of menace, danger, foreboding — of the sensed possibility that things will get worse, that evil will be the offspring of good. Revolutions disorientate people. They breed anxiety. Not only do many rediscover the obvious rule that the familiar normally serves as a comfortable home. They also learn at first hand that not everybody gains during revolutions, that indeed many lose out, and that everybody, through the course of revolutionary upheaval, fears to a greater or lesser extent that they will be pushed on to the side of the losers. The history of modern revolutions from the late eighteenth century onwards suggests that revolutions are never ‘the irruption of the masses in their own destiny’ (Trotsky), for the simple reason that they always — the Velvet Revolution was no exception — unleash the lust for power among jostling minorities of organized manipulators, who seek the ultimate prize: immense power over the lives of millions of others. During revolutions, that is to say, power struggles among political factions always break out. Within the old ruling groups, the knives are usually drawn. Groups of professional counter-revolutionaries are born. Within the ranks of the opposition, groups of professional revolutionaries possessed of great initiative, organizing talent and elaborate doctrines also make their appearance. At first, they appear to listen to their fellow citizens who are rebelling on the streets. Later, these revolutionary grouplets claim to represent them. Eventually, they supplant them, sometimes through violence. The professional revolutionists press home the need to avert counter-revolution and to revolutionize the revolution. The revolution is seen to be an irresistible necessity. This enables the revolutionaries to justify their actions, to sacrifice their victims to the great event, and to absolve in advance any guilt or crime that may be committed in the name of the revolution. Strangely, this idea of the necessity of the revolution is mixed up with the contrary presumption, among both the revolutionaries and their opponents, that human beings have absolute power over their destinies. And so revolutions are usually dangerous affairs. Revolutions are like hurricanes. Drawn into their forcefields, human beings find that it is possible to commit actions that posterity, out of sheer amazement and horror, finds it difficult to comprehend, let alone to justify.

The first day of the Velvet Revolution confirmed these maxims. Whatever observers may now think of the scale and causes of the events, the mayhem that followed undeniably scared many people, revolutionaries like Havel included. He noted that the authorities did their world-historical best to restore calm and to rebuild order and normality. On the morning after the events, on day two of the revolution, Communist Party newspapers reprinted the CTK communiqué, adding only that by ten o’clock in the evening the centre of Prague was peaceful again. The official press also reported some heavily doctored casualty figures: 7 policemen and 17 demonstrators had been injured; 143 people had been arrested and a further 9 detained for further questioning; 70 others had been caught flagrante delicto disturbing the peace; 21 others had been fined and released.

Quite the opposite message had meanwhile spread like fire through Prague. The word ‘massacre’ began to be heard everywhere. Whoever invented it either committed an unintended exaggeration or deliberately produced a white lie. But its effect was to arouse public indignation against the whole Communist system. As each hour passed, talk of massacre ensured that the radical resistance that had sprung up in the university faculties and theatres quickly spread into the streets. Televisions set up in shop windows ran videotapes of the police brutality. At scores of unofficial meetings and in theatres, cafés and pubs all over the city people began to talk of the need to stand up to the Communists, even to defeat them, for instance through strike action and public hearings about police brutality. Inebriated by their own power, crowds began to deface statues, rename underground stations, tear down Communist Red stars. Some people began to hold all-day vigils, lighting hundreds of votive candles at bloodstained sites, and then standing back in silence, as if in prayer.

Whatever fear and vacillation remained on the second day of the revolution suddenly evaporated with the extraordinary news, based on Western media reports that evening, that Martin Šmíd, a young student at the faculty of mathematics and physics, had died from injuries received the previous night. It later transpired that the report was untrue. The standard story is that Havel’s Trotskyite friend Petr Uhl had been approached by two StB agents who provided him with details of the death. Uhl was the director of a dissident press agency and in that capacity supplied Western agencies with the world-shattering news. Whether or not Uhl was handling the truth carelessly, or what the motives of the agents were, or why the dithering authorities subsequently spent a whole day searching for the supposed fatality, remains unclear to this day. It was subsequently alleged that an STB secret-police agent had infiltrated the demonstration, provoked it to change course, and then fell down, feigning death, to be carted away by an StB ambulance. The ploy was evidently backed by pro-Gorbachev Party bosses whose aim was to fire up the population, to discredit the hardliners, thus improving the chances of ‘the moderates’ retaining power. Whatever the case, the truth of the matter did not matter at the time. In thousands and thousands of minds, the death of a young student at the hands of the Communists during a demonstration to commemorate the death of a young student at the hands of the Nazis fifty years earlier proved that the two systems stood on the same continuum of intolerance, totalitarianism, violence.

With danger in the air, Havel was forced to grow concerned about his own personal safety. His friend John Bok especially criticized his habit of walking everywhere and of making his own way home at night after political meetings. He quickly convinced him of the need for protection.303 Several days into the revolution, long-haired, energetic Bok had organized a private police force to protect the body of the man who would prove to be its principal actor. The Force — ‘the boys’, Bok preferred to call them — operated from the outset according to the rules of military-police discipline. The thirty or so young men were not especially political. But they had grown tired of the Communist system and were alert to the high risks and dangers of this present moment in history, which their native intelligence told them was of historical significance. The Force was well briefed: their job was to protect the lilliputian figure, a man of the people, by operating in secret a rival force to that of the official StB, without it spotting and catching them. The Force looked and dressed like Czech athletes in training, which several of them were in fact. Full of energy, tall and physically agile, they wore track suits and trainers and were strictly forbidden to drink alcohol while on the job. They had excellent road sense and knew Prague like the backs of their big hands. Several were equipped with short-range walkie-talkies, which were used sparingly lest they were detected or monitored by the StB. All were skilled in the arts of seeing and shielding, without being seen.

The tasks of the Force were initially easy to execute: chauffeuring and ferrying Havel here and there all over Prague. Concealing his whereabouts. Keeping watch for the feared official police. Anticipating or foiling any plot they might be hatching to snatch and detain their man. Ushering Havel politely through small crowds of well-wishers. Making sure he shook and kissed hands in moderation, so that he could be on time for the next string of meetings. The problem of scheduling soon mushroomed in size and complexity. For the first time in his life, Havel found himself ever more trapped within a thickening forest of appointments. Individuals and groups, enjoying the new freedom to act with and against each other in opposition to the regime, wanted time with him, and he with them.

Gone for ever was the halcyon tranquillity of trilobite-hunting at Barrandov, peaceful walks through the woods at Hrádeček, long early-morning baths, sipping coffee laced with rum. Some mornings now began before first light. The days usually stretched unbroken beyond nightfall, and often well past midnight. The pace had to be quickened, kept up, quickened again. Amidst mounting chaos, appointments needed to be made and kept. Havel had to be reminded of them; alterations needed to be made; others had to be contacted as and when events demanded; routes and vehicles had to be co-ordinated; and, given the dangers of further police and army crackdowns, everything had to be executed quietly and invisibly.

The job of crowd control was not especially difficult at first. But the technique of gesturing Havel along his route with outstretched hands soon had to be replaced with flying wedges. As each day passed, and especially after the appearance of the first trolley cars adorned with banners reading Havel na Hrad (Havel for President), the Force found itself up against thickening walls of people, whose good nature was overpowered by its heaving numbers and, hence, the growing probability that Havel would be mobbed, trapped, knocked down, trampled, injured, wilfully hurt, assassinated even. No one, and certainly not Havel himself, knew the authorities’ intentions or tactics, especially after his daring act on the third evening of the revolution: to convene a meeting of citizens at theČinoherní klub theatre to discuss and to decide what now was to be done.

The wise political animal Havel did not know that the gathered group of revolutionaries was destined, in quick time, to lead the struggle against the old order, let alone that it would form itself into a shadow government. But he had the good sense to invite a broad and motley array of individuals and group representatives whose opinions captured something of the various hopes, fears, and angers sparked by the so-called massacre. The packed meeting included Charter 77 veterans, the Pen Club committee, members of groups like the Society for the Protection of the Unjustly Prosecuted (VONS), Art Forum, the Independent Students’ Union, the Czechoslovak Helsinki Committee, the Circle of Independent Intellectuals, Renaissance (Obroda), the Czechoslovak Democratic Initiative, and independent members of the churches, banned Christian and socialist parties, and other associations. That evening, on Sunday, 19 November 1989, at 11 p.m., after brief but spirited discussion, the meeting voted unanimously to form itself into a new citizens’ umbrella group called Civic Forum [Občanské fórum]. In the early hours of the next morning, it issued a proclamation. Signed by Havel and seventeen other representatives, the toughly worded document aimed to bring to justice those responsible for the massacre. It sought to remind the population of the tragedy that befell them after capitulating silently in 1968. It aimed as well somehow to split the ruling Communist Party by identifying some of its hardliners. The proclamation called for the resignation of the current Federal Minister of the Interior, František Kind, and Miroslav Štěpán, as well as those Communist leaders (like Gustáv Husák and Miloš Jakeš) who had actively supported the Warsaw Pact invasion in 1968. It went on to propose the setting up of an independent Civic Forum commission chartered to investigate the massacre and to punish those responsible. And, as if to remind everybody of the need to lift their political sights, it called for the release of all political prisoners, including those (like Petr Uhl) who had been arrested that day.304

It would have been easy for the authorities to pick off Havel and his Civic Forum colleagues. They instead kept their fingers off the trigger, probably because for the past two days, ever since the outbreak of the revolution, everything had gone badly for the Communist Party. The silent reprieve gave Havel courage that more could be done. He moved fast to seize the initiative, protected by the Force through all the confused twists and turns of the revolutionary maelstrom. From the moment Civic Forum was formed, Havel manifestly set his sights on becoming Leader of the Opposition. He busied himself initially in securing his immediate power base, for instance by helping to set up and monitor Civic Forum committees concerned with operations, technical advice, information, and planning of strategy. He paid special attention to keeping his fingers on the rapid pulse of events. His days were long and filled with scores of conversations, more or less confidential, laced with endless cigarettes, brandy and beer, snacks and cups of coffee. He quickly looked wrecked, as if to play the part of the rakish revolutionary leader burdened not by the weight of the past, but by the massive uncertainty about the fate of the present.

There are always moments in a revolution (as Jules Michelet pointed out) when actors feel as though normal mechanical time has vanished. This was certainly that moment. Sometimes Havel had the feeling that the revolution — he was now convinced that this was the right word to use — was moving too slowly, and at other times too fast. It never felt just right. Things often moved too slowly because people’s actions, including his own, quickly became ensnared within thickening webs of relations, obligations, problems, misunderstandings, all of which gave him and those around him in Civic Forum the feeling that their efforts were being diverted, dissipated, or bogged down in details. Yet events also sometimes seemed to move too quickly. Things happened and disappeared so fast that everybody had to hurry in order just to experience them. The revolution seemed to hurtle forwards at breakneck speed, with such force in fact that the proliferation of surprises and unforeseen events induced flutters and fears in everybody’s hearts. In either case, it felt to Havel as if the unfolding revolutionary events could not easily be brought to an end — neither that they could be halted nor that they pointed to a happy ending.

On board the revolution rollercoaster Havel worked hard through Civic Forum both to ensure its survival and to guarantee its role as the beating heart of the emerging opposition body. With his support, Civic Forum dispatched delegates all over the country with the aim of establishing brother and sister chapters. Attempts were also made to embarrass and paralyse the regime by sending delegations of Civic Forum representatives to visit all the strategically important state bodies, such as the Parliament, the Federal Government, the Czech Government, the Presidency, the Czech National Council, and the Ministry of the Interior. The delegations were typically met with sweet words or brick walls, but that did not matter because on each occasion the Civic Forum activists were chaperoned by cheering crowds, which gave the opposition the moral high ground and had the added effect of making the political authorities look as though they were paralysed by crisis. Havel, fearing that they would use violence, like cornered animals, lent his hand to the Forum’s efforts to calm public nerves and to appeal for absolute physical restraint within the ranks of the demonstrators, despite police provocations and rumours.

Among the many paradoxes of the Velvet Revolution — its name was drawn from the 1960s New York experimental rock band, the Velvet Underground — is that it began violently and continued throughout to threaten to rain down violence on a torrential scale. Havel told friends that he found the whole saga nerve-wracking, for he knew that any attempt by the authorities to impose martial law would throw everything into the pot of jeopardy. He also knew that the persistent and ineradicable threats of violence — symbolized by the omnipresent walls of grim-faced police dressed in riot gear — might at any moment puff up the street crowds into violent explosions. Everything rested on a knife-edge, especially after hundreds of police moved in on the fifth day of the revolution (Tuesday, 21 November) to surround and protect the building of the Central Committee. The sinister symbolism of that move was compounded by next day’s rumour, which ran hot through the street crowds, that all Prague schools and university faculties were being visited by security-police agents; that in nearby Pilsen militia leaders had urged Jakeš to ‘stand firm and reject reforms’ and to recognize that ‘force should be met by force’; and that 40,000 troops were closing in on the city to prepare a Beijing-style crushing of the Czech democracy movement.

Havel hoped against hope that everything would turn out well. Measured calculations dictated the conclusion that the regime would not crack down violently on its opponents. Moscow might not approve. The western enclaves of the Soviet empire were anyway in an advanced state of collapse (Communism had already peacefully collapsed in Hungary and Poland, and neighbouring East Germany was in turmoil). Violence would hardly bring much-needed economic reform or solve any other structural problems of the regime. Violence might well make the country ungovernable. A military crackdown would surely breed resistance from the emerging civil society. There would also certainly be a huge international outcry against a repetition of the Prague Spring solution. And yet within a revolutionary crisis of this kind, Havel sensed, reasoned calculations could count for nothing in comparison with the authorities’ fear-driven impulses. So he helped do some fire-fighting, as when he and Professor Jelínek from the Civic Forum leadership made several desperate telephone calls to the Pilsen militia leaders, who were indeed getting ready to issue live ammunition. The tactic of responsibly calling the militia’s bluff and sending off a thousand demonstrators to their buildings worked.

The success convinced Havel that the chances of a non-violent or ‘velvet’ outcome would partly depend on his winning leadership of the opposition. Nothing was certain. But a week into the revolution he had begun to look and act like the moral and political leader of the resistance to late-socialism. The revolution itself was proving to be a great spectacle. It enchanted both observers and participants alike, and so Havel, a master dramatist and compulsive planner of his and others’ moves, climbed eagerly on to a stage already clotted with countless actors. Edmund Burke’s remark to Lord Charlemont during the French Revolution, ‘What a play, what actors!’, applied just as well 200 years later to the Velvet Revolution, and particularly to Havel himself. His public quest to confirm his leadership — a show par excellence — began at the Prague theatre Laterna Magika. Havel chose that as the site to base the headquarters of Civic Forum, whose inner circles quickly began to function as a government in waiting.

There, in the smoky caverns of the Laterna Magika, he coordinated the huge task of drawing up blueprints for the future of the country, helped by a team of experts, including several frustrated prognostiks (academic economists), to whom the Jakeš government had refused to listen when the time had come for perestroika reforms: Dr Komárek, Dr Dlouhý, and his future enemy number one, Dr Klaus. Reporters from all over the world began to crowd into the theatre, hoping to get a glance or word from the becoming-famous playwright-leader. Havel tried to put some order into the chaos by organizing press conferences, among the first of which was held at 8.30 p.m. on 22 November. At an informal briefing beforehand, his furrowed face radiated confidence as he spoke of the past twenty years of post-totalitarian repression, the misuse of the word socialism, the organized lying about everything, including the Prague Spring and the recent massacre. He said that Civic Forum wanted to replace the powermongering, lies and corruption of the old order with a pluralist democracy. It wanted guarantees for independent economic activity, which was not the same as the restoration of capitalism.

Towards the end of the briefing, Havel said in jest to one reporter, Dana Emingerová, that if details of the briefing were published in the Czechoslovak press then he would pass on to her the prestigious Olof Palme Prize, which he had that day been awarded. In retrospect, the remark was highly revealing of the reigning ignorance within the opposition about the state of morale and fortitude within the upper ranks of the nomenklatura, who were now beginning to panic so wildly that they resembled the swine of Gadarene. Havel’s last remark at the briefing reinforced this impression. A messenger had just informed him that a highly secret extraordinary session of the Central Committee had just voted out the compromised leaders in favour of a reformist faction led by Štrougal. ‘This probable fall of the compromised calls for champagne,’ said Havel with a grin, without knowing that the Party session was not so extraordinary — simply because the whole of the Communist Party was in an advanced state of implosion.

Although it took several weeks for Havel and the rest of the inner circle of Civic Forum to realize that they had overestimated the power of the ruling party, he cunningly managed to manoeuvre it into its greatest public test of the revolution. The plan was to put the Party on trial before the emerging public opinion by inviting a senior Communist to address a public rally. The experience of addressing a public without rigging the setting, theme or outcome had almost been forgotten in Czechoslovakia since the military crushing of the Prague Spring. Havel reasoned that the Party leadership, well accustomed to deciding things in committees and behind closed doors, would probably be wrongfooted when exposed to the test of public-opinion-making. He personally had found unforgettable his public debut at Dobřís and more recently — eleven months ago, on 10 December 1988 — he had for the first time addressed a demonstration in Prague’s Škroup Square (so named after the composer of the national anthem). Czechoslovak television and amateur video images of that rally show the wispy-haired Havel up on the podium, dressed in a black leather jacket and a brightly coloured scarf, speaking into two loudhailers, attended by a young student, poking fun at the authorities, singing praises to citizens, evidently enjoying the stage performance immensely.305

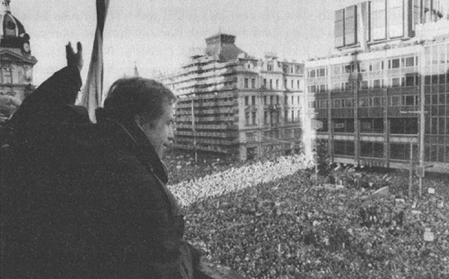

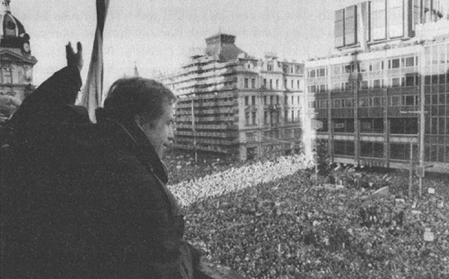

Havel had the chance to repeat this kind of performance on a freezing but sunny Tuesday, 21 November 1989, this time before an immense crowd of over 200,000 demonstrators squeezed into Wenceslas Square. It was the first time Civic Forum figures like Václav Malý, Radim Palouš, Milan Hruška, Karel Sedláček and Havel himself had appeared before such a large crowd. Although earlier that day the air had been rife with rumours about martial law and Chinese-style massacres, the crowd defiantly took refuge in its size, cheering the speakers standing up on the balcony of the Melantrich building, the headquarters of the Socialist Party, whose general secretary, Jan Škoda — a schoolmate from Poděbrady — was a founding member of Civic Forum. The wildest cheers of all were reserved for the nervous Havel. He made a tremendous impression as well on the police, many of whom were spotted sporting the national colours on their lapels and cheering Havel. His political career as Leader of the Opposition was now much clearer, and it was confirmed within hours by a secret approach to him from a leading Communist, Evžen Erban, sent by Premier Adamec to propose that secret negotiations about the future of the country begin immediately.

Little is known about that first contact with the Party, but Havel’s determination to look and act like the next leader of the country was revealed in the letters he immediately drafted on behalf of Civic Forum to Presidents Bush and Gorbachev. The letters aimed to inform them of the deep crisis in Czechoslovakia just before their planned talks in Malta. The quick unofficial replies he received made it crystal-clear not only that Bush favoured a breakthrough to political democracy, but also that Gorbachev, by refusing to back his Czechoslovak comrades with force, was defacto of the same opinion. Havel and the rest of Civic Forum drew courage. Their foray into foreign policy, which is what it amounted to, combined with the approach from Premier Adamec, served as the immediate backdrop for Havel’s direct backing for the Civic Forum plan to work towards a general strike by hosting a countrywide string of giant demonstrations designed to force the government on to its knees.

There were now large daily demonstrations in Prague, and a taste of things to come was provided by the next one after Havel’s Melantrich appearance. An estimated half a million people crushed into Wenceslas Square, amidst extraordinary reports and rumours. News was received of growing confusion within the upper echelons of the Party and of support for Civic Forum from a wide variety of groups and organizations, including the Slavia football club, the Prague Lawyers’ Association, the giant ČKD electronics plant, and Barrandov film studios, formerly the property of the Havel family. Demonstrators also knew of the demand for editorial freedom hurled by the employees of State Television at their Communist managers. And snippets of information were circulating fast about the unprecedented spreading of unrest to many towns outside Prague. In Bratislava, where the trial continued of Dr Čarnogurský, who was charged with defaming the socialist system by calling it totalitarian, up to 100,000 demonstrators, many of them workers from Slovnaft Petrol Complex, reportedly had turned out. In České Budějovice, 25,000 protestors braved pouring rain, while policemen searched student hostels for planted bombs. In Brno, perhaps 120,000 people came out in support of the local demand to widen the dialogue ‘to involve civil society’. In some cities, like the north Bohemian industrial town of Most, the authorities had tried to prohibit demonstrations, which took place regardless. The significant news also reached Wenceslas Square of the ‘disappearance’ of seventeen coachloads of Moravian militiamen, newly arrived in Prague to relieve colleagues now exhausted by five days on duty guarding state buildings. Havel told reporters that the militiamen had not been told where they should report for duty — such was the chaos in the capital’s police administration — and that consequently they had got lost in the huge crowd gathering for the 4 p.m. demonstration. The militiamen later tried to find accommodation, were refused everywhere they went, and presumably then found their own way back to Moravia, their ears ringing with the chief slogans chanted by the peaceful throng: ‘The Soviet Union: Our Model at Last! [Sovětský svaz, konečně náš vzor]’; ‘St Stephen’s Day without Štěpán! [Na Štěpána bez Štěpána]’; ‘Miloš Jakeš, it’s all over! [Miloši končíme]’; and a chant that must have thrilled Civic Forum’s leader, ‘Play Havel’s Plays! [Hrajte Havla]’.

And so came the weekend of the biggest peaceful demonstrations of all. Moved for reasons of space at the last moment to Letná Plain, high above the Old Town Square, the planned demonstrations on Saturday and Sunday, 25 and 26 November attracted great excitement. The Civic Forum leadership smelled victory. Popular fears of violent counter-revolution were at their lowest ebb. And the Communist leaders, plugging wax in their ears and shading their eyes, pretended to be busy with their official duties. On the day before the Letná demonstrations, the ageing Jakeš had appeared so calm that some of his senior comrades became convinced that he was actually insane. At seven o’clock that evening, Jakeš replied by suddenly announcing that he and his secretariat and politburo were resigning. The news was instantly relayed, in the style of the ancient Greeks, by a journalist who sprinted to Wenceslas Square, where the crowds that were still gathered there greeted the revelations with a roar.

The resignation resembled collective suicide. It was an act of grave political stupidity, and it convinced Havel and his supporters, who immediately afterwards drank a champagne toast to ‘A Free Czechoslovakia’, that the Party was dissolving into chaos. That was certainly the feeling on Letná Plain, where on the Saturday 750,000 people assembled, some of them having come straight from attending a special mass marking the canonization of Agnes of Bohemia in the Prague Cathedral, celebrated by the ninety-year-old Cardinal Tomášek and shown live for the first time by state television. The Letná demonstrators did not know that Štěpán had just been forced to resign and that President Husák had just agreed to halt criminal proceedings against eight people, including Miroslav Kusý and Ján Čarnogurský. The crowd was nevertheless thrilled to hear speeches from Havel and various other celebrities, and it was agreed by an enormous forest of hands that another demonstration at Letná would take place the following day, at 2 p.m.

With the scent of political victory in the freezing air, nearly a million demonstrators returned on the Sunday to cheer, shout slogans, jangle their keys and listen to the speeches. The gigantic crowd was told through loudspeakers of the Communist counter-demonstration at Litoměřice, where some 1,800 faithful Communists had gathered with shouts of ‘Long Live Socialism!’, ‘Long Live the Party!’, ‘Long Live the Army!’, ‘Long Live the Police!’, ‘We Shall Never Give Up!’, and ‘Who Is Havel?’. There were jeers and hoots of laughter, then respectful silence followed by some cheering and clapping as Alexander Dubček, the representative of both Slovak voices and of the aspirations of the Prague Spring, mounted the makeshift podium to speak of socialism with a human face and of the past twenty years as a period of national humiliation. There followed live music and a string of speakers, including police lieutenant Pinc. He received a mixed reception after apologizing personally to the crowd for police brutalities and trying to explain that the police themselves did not agree with the ruthless handling of the 17 November demonstration, and that they were only obeying orders. Student representatives replied by reading out a statement by the procurator-general, who acknowledged publicly that the police used excessive violence on the first day of the revolution. A large section of the crowd sounded amused, especially after a Charter 77 spokesman pointed out that not all political prisoners had yet been released. The chuckling turned into rapturous applause when it was announced that Petr Uhl — the first link in the chain of publicity of the massacre — had just arrived at the demonstration, straight from prison.

It was then Havel’s turn to stand up before the vast tidal sea of expectant faces. Dressed in black, wearing reading glasses, rocking nervously, to and fro, on his left leg, the man of the people began. ‘The Civic Forum wants to be a bridge between totalitarianism and a real, pluralistic democracy, which will subsequently be legitimized by a free election,’ he shouted into the microphone. ‘We want truth, humanity, freedom as well,’ he added, enveloped instantly in a cloud of thunderous applause. After thirty seconds he continued: ‘From here on we are all directing this country of ours and all of us bear responsibility for its fate.’306 Havel went on to announce that the Prime Minister of Czechoslovakia had been invited to speak to the crowd. Havel did not explain why, but those in the crowd who thought about it would have realized that the Civic Forum leadership had put their trust in Adamec as the only senior Communist leader whom they could trust. ‘Adamec! Adamec!’ some parts of the crowd began to chant, perhaps with the intention of exacting their pound of flesh.

Adamec initially lived up to Civic Forum’s and Havel’s expectations by telling the crowd politely that the government accepted all of their key demands. The crowd whistled. It roared with joy. But no sooner had Adamec performed well when he made the mistake of qualifying his opening statement. He revealed that he still knelt before the principle of the leading role of the Party by resorting to the ifs and buts for which he had always been famous. He was instantly repaid by the hostility of the demonstrators. Their sea of faces swelled up into a tsunami. It drowned out Adamec. They hissed and booed and heckled and taunted each sentence. Tension rose to the point where the Civic Forum marshals knew that either he was to be pulled from the podium or he would be swallowed up — suffocated, assaulted, even lynched — by the crowd. Adamec’s hunch that he could solve the political crisis and save the Czechoslovak Communist Party by appearing at Letná had gone hopelessly wrong. His attempt to outwit Civic Forum had backfired. So too had Civic Forum’s attempt to use the Party as a safe bridgehead into the post-Communist future. The revolution was now succeeding. ‘Our jaws cannot drop any lower,’ exclaimed Radio Free Europe.307 Communism’s time was up. The events boastfully predicted in the Prague scene a few days earlier — a prediction made by British writer Timothy Garton Ash that many thought a wild exaggeration — had come to pass. The political job of getting rid of Communism had taken ten hard years in Poland. In Hungary it had taken ten months. In neighbouring East Germany the revolution had taken ten weeks. In Czechoslovakia it had indeed taken just ten days.