“There is no better feeling to me than writing. I love to make a picture come to life and dance under my pen.”

—LOLITA PRINCE

The above quote comes from a homeless woman who is active in the Los Angeles Downtown Women’s Center’s writing workshop. When Lolita said, “I love to make a picture come to life and dance under my pen,” she expressed as good a definition of poetry as I know. Poets use words—only words—to create pictures for the reader. The dancing under the pen relates to the music of those words. A successful poem not only brings up a visual image of the subject, but through word choice, sounds, rhythm, and rhyme, it creates a physical reaction to enhance and reinforce the image.

Children love poetry. They love the music of it. They love anticipating rhyming words and saying them along with adults. This is the beginning of their reading. Studies show that children who hear poetry from a young age become proficient readers earlier than those not exposed to poems.

If this is true, why do editors frequently groan when they read picture-book manuscripts that incorporate rhyme? Why do they throw up their hands and beg, “Please! No more rhymed picture books!” The answer is simple. Most writers have failed to master the elements of good poetry. Yet writers persist. When they think of stories for children, they think of rhyme. It’s lively, and fun, so they give it a try.

You wouldn’t trust a doctor to perform your surgery if he hadn’t first studied medicine. You wouldn’t let a pilot fly your plane if she hadn’t taken flying lessons. And you wouldn’t hire a teacher if he hadn’t gone to college. But too many writers think they can write a rhymed picture book without any knowledge of poetry.

This chapter will help you determine your ability to write in rhyme and whether you first need to educate yourself about poetry.

We’re at that part of the book I warned you metrophobes (those who fear poetry) about earlier. Don’t panic. Take a deep breath. Now take another. I was a nervous wreck when I walked into my first poetry-writing class, but studying poetry is the best thing I did to strengthen my ability to write publishable picture books.

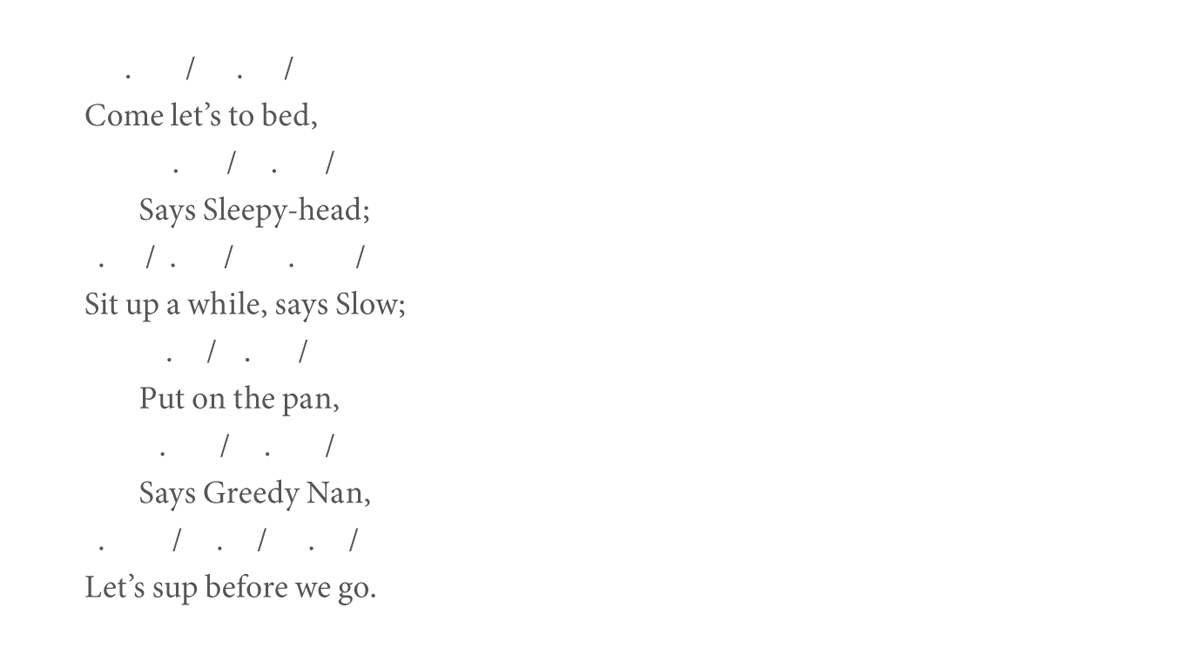

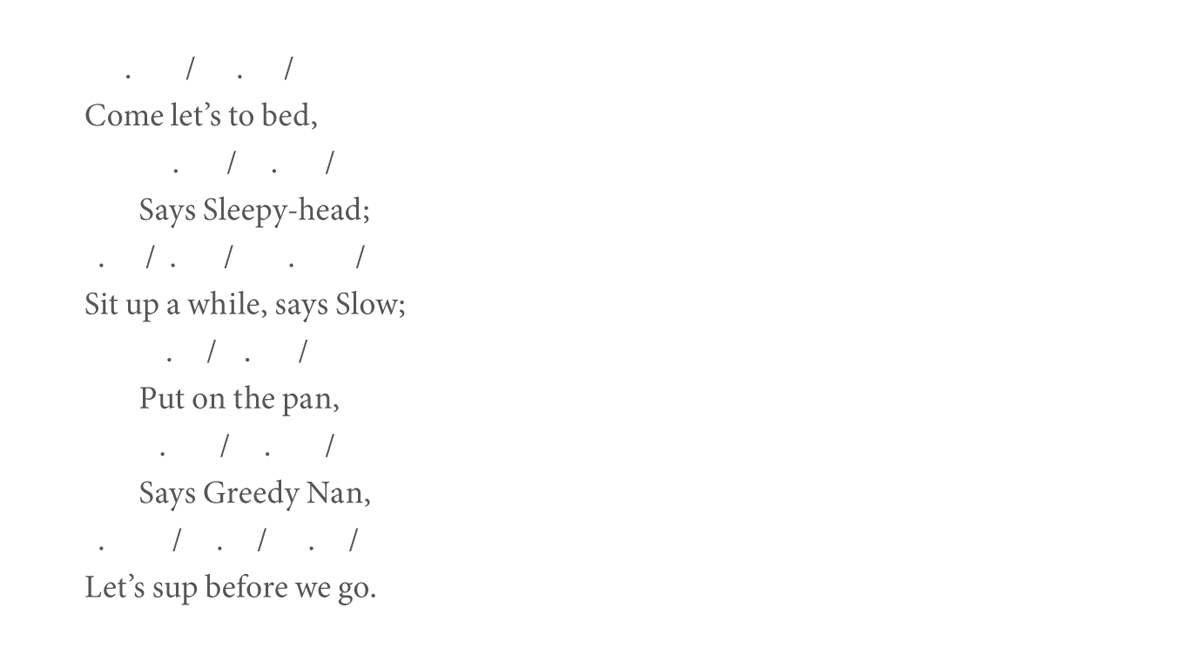

It’s time to take a dip in the rhymed, metrical poetry pool. I guarantee that by reading the next two chapters and taking practice swims, you and poetry will eventually get along fine. Let’s get our feet wet with four elements of good poetry—brevity, focus, consistent rhyme, and consistent rhythm. The first two elements have already been discussed in relation to picture books. To understand these concepts in relation to poetry, let’s look at that well-known nursery rhyme “To Bed!” by the prolific Mother Goose. Using this familiar work will help you spot errors more easily than you would in your poetic endeavors.

When I was in high school and assigned to write papers of a certain length, I often padded my work. After all, I had to make the assigned word count. Writing picture books, whether in prose or poetry, forced me and will force you to unlearn padding techniques. Picture books are short. Poems are short, too. Let’s look at our example below.

Come let’s to bed,

Says Sleepy-head;

Sit up a while, says Slow;

Put on the pan,

Says Greedy Nan,

Let’s sup before we go.

Mother Goose used only twenty-four words to tell us about bedtime for these three distinct personalities. Many writers get started writing a poem or a rhyming picture book and can’t stop. Students have shown me poems that go on for thousands of words. What a lot of work for nothing! Why nothing?

Remember we’re writing for children with short attention spans; they can’t sit still for long. War and Peace would never appeal to a five-year-old or even a ten-year-old. They simply can’t focus on such a long but fabulous book. So why do rhyming writers go on too long?

Sadly, too many writers lose their focus. Focus is staying on message, not going off on tangents. It’s following the poem or story road to the end without detours or side trips.

Writers lose focus in two ways. The first: They don’t have a focus to start with. They’re not sure what they’re writing about and maybe don’t realize they need to know. As discussed in chapter two, you, the writer, must think about what you’re trying to say. You don’t need to state it in your writing, but you need to know what it is. Otherwise, your writing will be like that house without a frame and collapse into a pile of “So what?” or end up a mere incident instead of a story.

Our poem “To Bed!” may be about three different characters, but it’s all focused on their going to bed. There’s nothing about what brought them to that moment or what they will do afterward.

The second: In poetry, writers lose focus because they’re having too much fun with rhyme and forget about the story, as I did here.

Come let’s to bed,

Says Sleepy-head.

It’s been a day

Of too much play.

We climbed a wall.

We tossed a ball.

We had a race—

A game of chase.

Slow takes a seat.

I’m feeling beat,

She yawns. She sighs.

She rubs her eyes.

I’m starved, Nan said.

Let’s bake some bread,

A cherry pie,

Oh me, oh my,

And pizza, too.

I’ll also brew

A pot of tea,

But just for me,

And then I’ll make

A layer cake

And one cream puff.

Still not enough!

This began as a story about three characters in specific relation to bedtime. Then I had so much fun explaining what caused Sleepy-head to be tired and demonstrating Slow’s personality through her actions. Being a fan of food, I imagined what Greedy Nan would eat. Couplets are addictive and easy to create. Once in the flow, I added too many details that distract from the rhyme’s purpose. It was a lark to write, but the focus changed too much.

There’s nothing like opening a rhyming dictionary and finding a word that takes you off in new directions, but stop and ask yourself: What’s the point? If the story is about these three characters at bedtime, details about their day, their food, and what Slow does when tired aren’t relevant.

As we’ve seen from the above example, rhyming, or the repetition of sounds, can be fun. Unfortunately, many newcomers who try to write a rhyming picture book don’t understand that rhyming must be consistent. Let’s look again at “To Bed!”

Come let’s to bed, | (a) |

Says Sleepy-head; | (a.1) |

Sit up a while, says Slow; | (b) |

Put on the pan, | (c) |

Says Greedy Nan, | (c.1) |

Let’s sup before we go. | (b.1) |

Those letters at the end of each line let you know which lines rhyme. See how we have a repetition of sound at the end of the lines in an aabccb pattern? There are three sets of rhyming lines, but each of these rhymes differently. If there is a number after the letter, as in line two, that means the ending word beside it rhymes with an ending word from a preceding line but is not the same word. If this poem had a seventh line that read, “They’ll share; I know,” the appropriate designation would be b.2. Unfortunately, trying to maintain consistent rhyme patterns leads beginning writers to make unwise word choices such as using words that rhyme but don’t add to the overall meaning, or forced rhyme, as in the following example.

Come let’s to bed, | (a) |

Says Sleepy-head; | (a.1) |

Sit up a while, says Slow; | (b) |

Put on the pan, | (c) |

Says Greedy Nan, | (c.1) |

Let’s sup before we go. | (b.1) |

I’ll mix and make | (d) |

A yummy cake. | (d.1) |

It won’t take long; I know. | (b.2) |

“I know” is only there so I can rhyme with “slow” and “go.” If you’re going to write a picture book in rhyme, every word must advance your story.

Rhyming leads to another problem. It can make your picture-book poem too predictable. You don’t want your reader to be able to guess every rhyming word. This most often happens when each line is a complete sentence, as in the following:

Come let’s to bed.

Lay down your head.

Sit up a while, says Slow.

I’m Greedy Nan.

Put on a pan.

Let’s sup before we go.

Create some spill-over lines (sentences that don’t end when the line does), so your rhyming will not be so predictable. This original poem, like many Mother Goose poems, breaks in obvious places, so its rhyme words are fairly obvious.

Here’s an example from one of my poems to demonstrate how spill-over lines add freshness. This poem is titled “Spider to Owl” and is written as a one-way conversation.

Owl, can’t you watch

the direction you’re going?

Your wing ripped my web!

You have no way of knowing

the rebuilding it takes.

I don’t have your talons,

or sharp curvy claws.

I have to rely on

my skills as a lacey,

white tablecloth spinner

to tempt in the bugs

I crave for my dinner.

Hear me, I beg you,

night’s quiet flier!

Please do your soaring

a little bit higher.

Notice how some of the rhyming words fall in the middle of a sentence. Beginning writers striving for a perfect rhyme scheme often use unnatural sentence inversions, as in the following.

Don’t beat your drum.

To bed, now come.

But I’m not tired, says Sue.

I want to eat

some cake, yum-sweet.

I’ll share a piece with you.

If line two were written in modern diction, it would be: “Now come to bed.” For line five to sound more like everyday speech, the adjective would need to come before the noun: “some yum-sweet cake.”

In our rhyming picture books, we want the writing to sound as natural as normal conversation. While poets may have gotten away with sentence inversions years ago, don’t let your poem today sound stilted and old-fashioned. If you are tempted to use forced rhyme or sentence inversions to keep your rhyme consistent, resist the temptation!

On the other hand, too many writers are unwilling to spend the time to establish and maintain rhyme patterns. They may be unaware of the importance of consistency, so they break the rhyme pattern, as in the example below.

Come let’s to bed,

Says Sleepy-head;

Sit up a while, says Slow;

Put on the pan,

Says Greedy Nan

Let’s sup before we go.

A great idea!

And we can read

A silly comic book.

These last three lines are jarring because the listener has accepted the pattern set up in the first six lines of a, a1, b, c, c1, b1, not only in his ears, but in his body. He expects this pattern to continue, in the same way we expect the sun to rise in the east and set in the west. Imagine what would happen if the sun suddenly rose in the north and set in the south! We would be thrown off-balance big-time. To a lesser degree, we were thrown off-balance by the last stanza added to the Mother Goose poem.

You may rightfully wonder if there are times when it’s okay to break the rhyme pattern. The answer is “Yes.” But only break the rhyme scheme to echo a change in the action of your poem. For instance, if the action in your poem is slowing down, you might insert an extra line to echo that slower movement. If the action in your poem speeds up, you might even delete a line, thereby bringing the rhymes closer together. Often writers change the rhyme scheme at the end of a poem (or a rhyming picture book) to signal the finish. Perhaps they write a nice rhyming couplet, thereby breaking the abcb pattern established throughout the piece.

It isn’t only a lack of brevity, focus, and rhyme that makes editors groan over poem picture-book manuscripts. Rhythm, too, is a key element of successful poem picture books. It’s also the element writers have the most trouble understanding. It’s time to take a deep breath and remind yourself that you can do this. If I could learn this, believe me, you can, too.

As with rhyme, the key is consistency. Don’t be fooled into thinking that if you can count syllables, you have mastered rhythm. Rhythm is not syllable count; it’s counting stresses and rhythmical feet. Rhythm is a pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables. Look at our example poem, where I have placed slanted lines above the words to indicate which beats are stressed.

In this poem, we have a soft beat followed by a stress, . /, otherwise known as an iambic rhythm. The soft beat and stress together form one metrical foot. In the lines above, the first, second, fourth, and fifth consist of two iambic metrical feet. The third and sixth lines have three iambic feet. While every line does not have an equal number of feet, the overall poem has a repeated pattern of two feet, two feet, three feet. When writing a story in rhyme, you must create a consistent pattern in your number of feet, or else you will jar the reader, as would the following poem.

It’s time we go to bed,

Yawns Sleepy-head.

Sit up a while, says Slow.

I’d rather cook a treat. Get out the pan,

Says hungry Greedy Nan.

Let’s eat and watch a scary video.

In this example, I kept the same iambic rhythm but paid no attention to how many feet in each line. Again, let me emphasize that poetry written in a lock-step rhythm often needs to be broken but only if it echoes a change in the story’s action. I did this in my book Everything to Spend the Night. The poem is iambic and has four metrical feet per line until the moment below.

The little girl denies she’s sleepy in a line that is out of sync with the established pattern, indicating, not only in words but in the music (or lack of music), that a change is coming. The next line may have four rhythmic feet again, but the iambic rhythm is broken. The last line returns to the book’s characteristic iambic tetrameter (four feet) because everything is finally okay.

Here’s what happens when the writer uses no rhythmic pattern at all (different rhythms and a different number of metrical feet) but sticks to a consistent rhyme scheme:

Shouldn’t we maybe think about bed?

Yawns a very sleepy head.

I’d rather stay up and finish this book, says Slow.

First, I’ll bake a cake in this pan,

Says a famished-for-sweets Nan.

You can each have a piece before we go.

I have to cover my ears reading this aloud. Can you hear how no rhythm translates to no poem?

Sometimes new writers use old-fashioned language to make the rhythmic pattern consistent:

’Tis time for bed,

Says Sleepy-head.

Don’t do this! Your poem will be outdated before your editor reads the second line.

If you still want to write your picture book using rhythm and rhyme, you must become familiar and comfortable with the following four basic rhythms.

We saw an example of this in “To Bed!” Each iambic foot starts with a soft beat and is followed by a hard beat. A good way to remember this is by thinking of the nonsensical sounds da DUM. An iambic foot is designated by . /, a period and a slash, and it is considered an upbeat—rising and happy—rhythm. Examples include beneath, before, betwixt, between, the bat, the ball, and a score. An iambic sentence might be It’s time to buy a loaf of bread. Iambic meter is the most commonly used rhythm, probably because it echoes one’s heartbeat.

Each anapestic foot starts with two soft beats and ends with a hard beat. Its nonsensical sounds would be da da DUM, designated with . . /, or two periods and a slash. You’ll find it in the words underscore, interlock, and disagree and in phrases such as at the lake, in the sand, a shy dog. This is an even happier, more upbeat rising rhythm than iambic. Using anapest signals to the reader that you are writing something humorous. In my book ’Twas the Late Night of Christmas, a new take on Clement Clarke Moore’s “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (“The Night Before Christmas”), I copied his almost-perfect anapestic rhythm. Here’s my opening line: “’Twas the late night of Christmas, when all through the house, everyone was exhausted, even the mouse.”

Each trochaic foot starts with a hard beat and is followed by a soft beat. Its nonsensical sounds would be DUM da, designated first by a slash and then a period (/ .). It’s found in the words diving, quickly, under, and nation and in phrases such as eat this, read slow, and go in. Here’s a trochaic sentence: Don’t you drink that water. The trochee tends to be used in sadder, perhaps more serious, poems.

Each dactylic foot starts with one hard beat and is followed by two soft beats. Its nonsense sounds are DUM da da, designated with a slash and two periods (/ . .). You can find it in the words stealthily, natural, and airiness or in phrases such as apples and, under the, and beating him. A dactylic sentence might read Munching fresh grass, the small snail overwhelmed by its tastiness waved his thin feelers with gratitude. This downbeat, heavy rhythm is most often found in poems that deal with serious matters.

Now you have had a quick overview of the four basic rhythms. That wasn’t so bad, was it? If you want to write rhymed picture books, you must be able to differentiate between the rhythms and create them consistently. I would suggest clapping or drumming each one out and then memorizing poems in each of the rhythms. Recite them until you feel comfortable with each one. To help you do this, here are four of my poems about rhinoceroses, each written in strict meter.

Old Rhino’s frame

is built too thin.

It’s way too small

for fitting in

the folds and wrinkles

of his skin.

See young Rhino. His skin, how it sags,

hangs in wrinkles, and folds!

So no matter his age,

You’d assume that he’s old.

Rhino’s wrinkles hang so loosely,

like a sweater, big and baggy.

He should wear a skin more fitting,

not so oversized and saggy.

Poor old Rhinoceros

tired of rain’s pitter and pattering,

drenched from drops’ splattering,

took off to search for a

place more hospitable.

Staggering, swaggering,

Wandering far and meandering,

finding a dry spot eventually,

just as the rain began tapering.

Please note all of these poems are written in mostly strict meter and therefore may feel stilted, but they work for the purpose of helping you learn rhythm. When you feel comfortable with these four basic rhythms, feel free to combine them so you don’t sound like Dr. Seuss, who sticks to a tight rhythm. In If Animals Said I Love You, I combined the upbeat iambic and anapestic rhythms so my poem didn’t feel sing-songy, as you can see in this couplet:

To feel comfortable with these different rhythms, read poetry. Determine the predominant rhythm, and mark the stresses. It’s imperative for rhythm to feel as comfortable as an old sock. If you’re not sure where the stress comes in a specific word, look it up in a dictionary.

However, stress may fall differently depending on the word’s placement in the sentence. For example, the word honey is a trochaic word, with the stress on the first syllable. But if the words preceding and following it create the phrase taste honey now, the stress would be on taste and now, with no stress on honey at all. And if I wrote, “Taste the honey now,” the stresses would appear over taste and hon and now. What words are stressed is determined by each one’s relationship to others in the line. So how do you know which words or syllables are stressed?

Read them aloud as if they were normal sentences, not poetry. That way you’re more likely to hear where the real stresses fall. Another approach is to ask someone else to read your lines and pay close attention to where they put the stresses.

Let’s see how well you identify the rhythm in these lines.

ANSWERS: 1. trochee 2. iamb 3. dactyl 4. anapest 5. trochee 6. iamb 7. trochee 8. anapest 9. dactyl 10. iamb 11. anapest 12. dactyl

Perhaps you did well on this quiz and feel comfortable using rhythm and rhyme. If you’ve decided you would like your story to be a poem, your newfound knowledge of the form should protect you from its potential pitfalls. On the other hand, if you have decided a poem picture book is not for you, then there is always prose.

Choosing to write prose does not give you license to abandon poetry. A picture book does not need to be a poem, but it must be written poetically, and we’ll talk about that in chapter fifteen.