Lisette Model, Louis Armstrong, c. 1956. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Museum. © Lisette Model Foundation Inc. (1983).

Over the long run of human history, the constant presence of beauty helps call us to the work of repairing injuries in the realm of injustice.

—ELAINE SCARRY1

It fixed me like a statue a quarter of an hour, or half an hour, I do not know which, for I lost all ideas of time, ‘even the consciousness of my existence.’

—THOMAS JEFFERSON2

In the face of war, he would ensure that they remembered the power of aesthetic force. Few else would have dared. After all, the crowd was living out the consequences of America’s greatest failure with their lives. Nearly one in four men would die for it during the nation-fracturing Civil War.3 They had come to Boston’s Tremont Temple to hear what the path toward a true union might mean. No one was expecting to hear what the speaker thought it would take to mend the nation’s foundations, though they would listen. For it came from this man, the “volcanic,” near-peerless orator, one of the nation’s greatest statesmen in importance if not in title, who had earned an oracular reputation as that of a “prophet,” advocating for acts that, soon after, came to pass—the freedom of enslaved men and women who crossed over into Union territory, arming African-Americans in the military, and a president-issued Emancipation Proclamation.4 At the age of twenty-three, at a time when orators “were analogous to star athletes” and “the stage” could resemble a “boxing ring,” his will, skill, style, and intellectual prowess proved to nearly all that “this is an extraordinary man” as one journalist put it, “cut out for a hero . . . As a speaker he has few equals.”5 He may have sensed that what he was to advocate was unexpected. He was, after all, a man of action. President Abraham Lincoln, then considered by many of his close advisors to be a failure before his reelection, sought his counsel on the subject of emancipation. In a two-hour, one-on-one meeting, Lincoln requested, should the war end without abolishing slavery, that he spearhead a federally sponsored underground railroad, helping the enslaved to go North.6 Now in Tremont Temple, what the orator was about to tell the audience seemed like a mere trifle in contrast, but Frederick Douglass was sure, even in the face of war, that the transportive, emancipatory force of “pictures,” and the expanded, imaginative visions they inspire, was the way to move toward what seemed impossible.7

An encounter with pictures that moves us, those in the world and the ones it creates in the mind, has a double-barreled power to convey humanity as it is, and, through the power of the imagination, to ignite an inner vision of life as it could be. The inward “picture making faculty,” Douglass argued, the human capacity for artful, imaginative thought, is what permits us to see the chasm accurately, our failures—the “picture of life contrasted with the fact of life.” “All that is really peculiar to humanity . . . proceeds from this one faculty or power.”8 This distinction of “the ideal contrasted with the real” is what made “criticism possible,” that is, it enabled the criticism of slavery, inequity, and injustice of any kind.9

It helps us deal with the opposite of failure, which may not be success—that momentary label affixed to us by others—but reconciliation, aligning our past with an expanded vision that has just come into view.

It may have seemed unusual, even unthinkable, as if Douglass was asking the gathered crowd to look at a single flower while flying down a perilous path on the back of a galloping horse. They had likely come expecting to hear a lecture about the Civil War and its Union-slashing effects rather than an ode to the power of visual imagination. Yet there Douglass stood in Boston’s famed Tremont Temple—the integrated church one block from Boston Commons where he had delivered a commemorative address on the anniversary of John Brown’s execution a year earlier, and where he would go on January 1, 1863, to hear the news of Lincoln signing the Emancipation Proclamation “on the wires” via a Samuel F. B. Morse–devised telegraph.10 Lincoln, too, had spoken at the church, as had abolitionists of the day, from Brown to William Lloyd Garrison. Now, early in 1861, with the war just begun, the crowd was beginning to pay for combat’s consequences with their lives. We will never know how he said it, in a stentorian or a subdued tone, but we do know that the audience was largely silent—his speeches “completely carried away” his audience, Elizabeth Cady Stanton recalled—as he focused on the critical role of what some might consider irrelevant in the face of a nation-severing conflict.11

Douglass made the case for art before science would show it: The “key to the great mystery of life and progress” was the ability of men and women to fashion a mental or material picture and let his or her entire world, sentiments, and vision of every other living thing be affected by it.12 Even the most humble image held in the hand or in the mind was never silent. Like the tones of music, it could speak to the heart in a way that words could not. All of the “Daguerreotypes, Ambrotypes, Photographs and Electrotypes, good and bad, [that] now adorn or disfigure all our dwellings,” Douglass said, could allow for progress through the mental pictures that they conjured. He went on to describe “the whole soul of man,” when “rightly viewed,” as “a sort of picture gallery[,] a grand panorama,” contrasting the sweep of life with the potential for progress in every moment.13 From the famed orator and abolitionist came one of the earliest articulations of how the private function of aesthetic force operates in public life. He was interested in the emancipatory quality of an aesthetic experience and the way it permeates the everyday.

Perhaps most surprising may not be that he said it, but when he did—at a time of unthinkable retrenchment and national fracture, when there was blood on the fields. In his first meeting with Lincoln, Douglass had turned up at the White House in August of 1863, traveling down by train without an appointment and sitting down with those who looked as if they had been waiting a week (and some had). Douglass sent the card announcing his arrival up the stairs. Within minutes, Lincoln received him. The Civil War president considered Douglass to be “one of the most meritorious men, if not the most meritorious man in the United States.”14

The crowd would recall, too, what Douglass had once uttered—violence and force may be the only way out. He would not have been surprised if “Old Testament retribution” broke out through a Southern slave insurrection. It would have been as natural as the eruption of “slumbering volcanoes.”15 It was a time when most saw incendiary force as indispensable; “I have need to be all on fire, for I have mountains of ice about me to melt,” abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison had said.16 Douglass took it further, saying that “it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake . . . the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed.”17 Yet he had hinted at times that talk and action were not all that it would take to mend the nation’s fracture as he addressed the more serious mood of the country. Those expecting to hear a two-hour speech the week that Emancipation would take place only heard a “ten-minute homily” that day at A. M. E. Zion Church in Rochester. “This is scarcely a day for prose,” but instead, “a day for poetry and song, a new song.”18

On the eve of Emancipation, eliminating the line between liberty and slavery by law, the nation was focused on another kind of justice that no law could correct—the ability to reconcile your dream with your reality.19 The older notion of a “self-made man” was tested after the abolition of slavery upheld the two main tenets of American life—equality and what Lincoln called the “new birth of freedom.”20 Erasing the dichotomy of liberty and slavery would put even greater pressure on what “success and failure”—increasingly unmoored from financial position, but determined by character, agency and vision—would come to mean in public life.21 Douglass was not only speaking about national justice, but what reconciliation would mean for each individual.

The course of our lives, Douglass argued, resembles “a thousand arrows shot from the same point and aimed at the same object.” After leaving their starting position, the arrows are “divided in the air” with only a few flying true, as he put it, “matched when dormant” but “unmatched in action.” Bridging the gap between sight and vision, which often comes through aesthetic force, is part of what made the difference.22

The words to describe aesthetic force suggest that it leaves us changed—stunned, dazzled, knocked out. It can quicken the pulse, make us gape, even gasp with astonishment. Its importance is its animating trait—not what it is, but what it does to those who behold it in all its forms. Its seeming lightness can make us forget that it has weight, force enough to bring about a self-correction, the acknowledgment of failure at the heart of justice—the moment when we reconcile our past with our intended future selves. Few experiences get us to this place more powerfully, with a tender push past the praetorian-guarded doors of reason and logic, than the emotive power of aesthetic force.

What forces us to see our errors, collective failures, ones too large to ignore and personal, perceptual ones of our own? Argument alone is not enough to make men good, Aristotle said.23 Reason does not govern completely, as the example of Odysseus lured by the Sirens’ song shows us. A cogent lecture on the topic by Yale philosophy professor Tamar Gendler outlined the way in which the non-rational takes over in everyday life, using an example of what would happen if we were to stand on a piece of glass at a peak point at the Grand Canyon over the coursing Colorado River. The rational part of us would know that we’re safe on the glass, but being “affected by this visual stimulus” is enough to cause physiological sensations, which we may sense as trembling.24

“We all have a blind spot around our privileges shaped exactly like us,” Junot Díaz has said, and it can create blindness to failures all around.25 It results in the Einstellung effect: the cost of success is that it can block our ability to see when what has worked well in the past might not any longer. In the face of entrenched failure, there are limits to reason’s ability to offer us a way out. Play helps us to see things anew, as do safe havens. Yet the imagination inspired by an aesthetic encounter can get us to the point of surrender, making way for a new version of ourselves.

Our reaction to aesthetic force, more easily than logic, is often how we accept with grace that the ground has shifted beneath our feet.26 “Art is a journey into the most unknown thing of all—oneself,” architect Louis Kahn stated. “Nobody knows his own frontiers.”

Aesthetic force can alter vision. When an experience astonishes us, we can conjure up an image that we mistakenly recall as fact. Academy Award–winning visual effects supervisor Robert Legato discovered this phenomenon when working on feature films from Martin Scorsese’s Hugo and The Departed to James Cameron’s Titanic. Legato’s powerful cinematic moments re-create historic events, but he doesn’t reproduce them with fidelity. He makes up a compilation of images culled from what viewers state that they recall seeing, feeling, and in turn believing was in front of their eyes. He grew curious about how the audience viewed his scenes—the ones he wanted to astonish, to evoke poignant, powerful emotion—and had a conversation that became an experiment. When he was creating footage for the Ron Howard–directed feature film Apollo 13, an astronaut who had been on this seventh Apollo mission came to the film set as a consultant to check on the veracity of the events shown. The astronaut viewed footage of the actual shuttle blasting off with the red gantry arms rotating out of the way alongside the fabricated footage from the film. Both looked “wrong” to him. “When we’re infused with either enthusiasm or awe or fondness . . . it changes what we see,” Legato said. “It changes what we remember.”27

Daniel Schacter, the Harvard psychologist whose research on memory may one day change how we consider its function in our lives, posits that instead of simply recording the past, “memory is set up to use the past to imagine the future” and “its flexibility creates a vulnerability—a risk of confusing imagination with reality.”28 This can result in “false memories,” the ones that so stunned Legato. Factor in our “positivity bias,” our tendency to recall the impactful and positive over the mundane, and it becomes clear that astonishment can change our view of the world.

Recently psychologists such as Jonathan Haidt and Sara Algoe have begun to measure how awe or elevation systematically results in generosity and altruism. A sense of “vastness” seems to inspire that in us.29 Yet philosophy considered it before psychology ever would. Beginning with Plato, philosophers have had a common concern about how our responses to aesthetics can sideline cognitive defenses. Two thousand years ago, in the first century CE, Longinus understood that something akin to “transport” happens when we feel moved by “elevated language,” that does not occur with rational “persuasion.”30 It was a truth that Leo Tolstoy declaimed a century or so ago: our response to art has the agency to do what “external measures—by our law-courts, police, charitable institutions, factory inspections” cannot.31 Centuries later, we sense it still, as did Tolstoy, John Keats, and art critic Michael Brenson made the rare argument that “the aesthetic response is miraculous. Such an astonishing amount of psychological, social, and historical information can be interwoven into a single connective charge that a lifetime of thinking cannot disentangle the threads.”32

We permit a new future to enter the room with these startling encounters. A young boy from Austin, Texas, Charles Black Jr., stood and knew it when he was just sixteen years old, thinking he was going to a coed social at the Driskill Hotel in his hometown in 1931. It was a dance, the first in a session of four, yet he remained transfixed by an image that he had never seen before. The trumpet player, a jazz musician whom he had not heard of, performed largely with his eyes closed, sounding out notes, ideas, laments, sonnets, “that had never before existed,” he said. His music sounded like an “utter transcendence of all else created.” He was with a friend, a “ ‘good old boy’ from Austin High,” who sensed it too, and was troubled. It rumbled the ground underneath them. His friend stood a while longer, “shook his head as if clearing it,” as if prying himself out of the trance. But Charles Black Jr. was sure even then. The trumpeter, “Louis Armstrong, King of the Trumpet” as it turned out, “was the first genius I had ever seen,” Black said, and that genius was housed in the body of a man whom Black’s childhood world had denigrated. The moment was “solemn.” Black had been staring at “genius,” yes, “fine control over total power, all height and depth, forever and ever,” and also staring at the gulf created by “the failure to recognize kinship.” He felt that Armstrong, who played as if “guided by a Daemon,” all “power” and lyricism, “opened my eyes wide, and put to me a choice”—to keep to a small view of humanity or to embrace a more expanded vision—and once Black made that choice, he never turned back. This is what aesthetic force can do—create a clear line forward, and an alternate route to choose.

Lisette Model, Louis Armstrong, c. 1956. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Museum. © Lisette Model Foundation Inc. (1983).

Later Black would say that, in many ways, this was the day he began “walking toward the Brown case, where I belonged.” Black would go on to join the legal team for the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case that persuaded the U.S. Supreme Court to unanimously declare segregation unlawful, and become one of the preeminent constitutional lawyers in the country.33

Like an unwelcome guest at a tightly guarded affair, the power of aesthetic force can be “haughtily dismiss[ed],” though it can get us to a point of self-correction.34 It has a hidden life in the personal form of justice. Black never forgot it. He held an annual Armstrong listening night at Columbia and Yale, where he would go on to teach constitutional law, to honor the power of art in the field of justice and the man who caused him to have an inner, life-changing shift.

Out of the “great artists in my time . . . it just happened that the one who said the most to me . . . was and is Louis,” Black said. Whatever is melodic, lyric, or poetic that gets us to this place can be catalytic in a way that few other things can. Yet it was fitting that for Black it was jazz, built as it is on the art of sounding out longing, as we hear in much of American roots music, specifically the blues. The melody of a song about heartbreak suggests that we believe life will improve, yet in its bittersweet tones we remind ourselves that sometimes the only way out is through.35

“Pictures have a power akin to song,” Douglass said. “Give me the making of a nations [sic] ballads, and I care not who has the making of its Laws.”36 The foundations of progress rest on twice-stamped improbability, once from the fractured foundations we need to mend, and again from stomping on its ground in a protracted tangle with failure, attesting to the desire for more. Social justice, no matter its kind, comes from more than critique and counterstatement, but from wrestling with seeming failure—what haunts us and what we would rather not inhabit, the gulf between what is and what should be. The tool we marshal to cross our gulf is irrevocably altered vision.

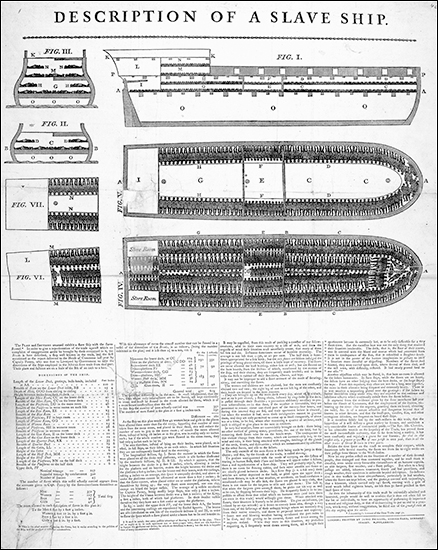

How many movements began when an aesthetic encounter indelibly changed our past perceptions of the world? It was an abolitionist’s print, not logical argument, which dealt the final blow to the slave trade—the broadside of Description of a Slave Ship (1789). The London print of the British slave ship Brookes showed the dehumanizing statistical visualization with graphic precision—how the legally permitted 454 men, women, and children might be accommodated (though the ship Brookes carried many more, up to 740).37

Description of a Slave Ship. (London: James Phillips, 1787). © The British Library Board. All Rights Reserved. 1881.d.8 (46).

The contrast between reality and the image it conjured in the mind was intolerable enough to abolish the institution and was the evidentiary proof of slavery’s inhumanity used in Parliament hearings.

Many credit the awe over Earthrise, the photograph taken from Apollo 8 orbiting the moon in 1968, with galvanizing force for the environmental movement.

Seeing images by Carleton Watkins of Yosemite Valley’s granite cliffs convinced Lincoln to sign legislation in 1864 that would lead to the establishment of the National Park Service.38 It is embedded so deeply in the private lives of our more public shifts that we can forget it is there until a poet is jailed in a repressive regime, when his books are banned—there is a force to the images that they inspire that has a straight line to justice, and its mechanism can spark an inner alteration.39

NASA / William Anders, Earthrise, 1968.

It is similar to the phenomenon of the unfinished. When we’re overcome by aesthetic force, a propulsion comes from the sense that, until that moment, we have been somehow incomplete. It can make us realize that our views and judgments need correction. It can give these moments “elasticity” and “plasticity”; as Elaine Scarry writes about the force of being moved by beauty—“momentarily stunned by beauty, the mind before long begins to create or to recall and, in doing so, soon discovers the limits of its own starting place, if there are limits to be found . . .”40

Douglass knew this from his own life. Born into bondage, he decided to seek his freedom after he saw a simple, seemingly innocuous image of sailboats on the Chesapeake Bay, gliding with a rightful ease that he had never felt. He stood and “traced” their path moving off to the ocean, powered by the currents, and then thought that he, too, would “take to the water” and go one hundred miles north.41 He would set down these moments in words—probing and exact—with a pen that he would often lay in the bored-out “gashes” in his feet. They had been cracked open by frost from times when he had endured winters enslaved in Maryland.42 He told his story through autobiographies that garnered him wide acclaim (and a warrant for his life—as we know, he fled to Britain to escape capture and a return to slavery). My Bondage and My Freedom (1855) sold 5,000 copies in the first two days.43 John Whittier was not alone in considering it the headwaters of a “new, truly national literature.”44 Yet Douglass knew that the key to change lies in the literature of thought pictures we carry born out of contrast. “Poets, prophets and reformers are all picture makers—and this ability is the secret of their power and of their achievements,” he said. “They see what ought to be by the reflection of what is, and endeavor to remove the contradiction.”45 This penetrating vision went far beyond a theory of our response to pictures. It described the chrysalis nature of becoming.

Today, saturated with images, we live in a world where aesthetic force is alternatively so self-evident, so easily dismissed, that we move forward through its veracious power without realizing it. Douglass was speaking at a time when aesthetic force could not be forgotten. Then the new inventions of photography, microscopes, and telescopes had begun to give validity to what people could before only imagine. Many had started trying to take pictures of the granular surface of the moon as soon as Daguerre’s photographic method was announced—constructing images of what we could envision, but not yet fully see.46 Rampant visual deception, from frauds to humbugs to optical illusions, also had the power to confound and challenge the authority granted to sight alone. Each prompted the question, “How do I know what I am seeing is real?” Being skeptical of what the eye could see was a sign of wisdom; seeing reality justly meant accepting the limits of sight.47

The authority then lost by the eye was the gain of the imagination. Not seeing what was in front of everyone’s view was disconcerting. Perhaps our most well-known example came from the time in 1872 when California tycoon Leland Stanford was curious about whether all four legs of a running horse ever leave the ground at the same time while galloping. At that point, before the invention of stop-motion photography, it wasn’t clear. He decided to hire Eadweard Muybridge to photograph his horses mid-run.48 It was a similar impulse to the one that occurred just after the invention of the daguerreotype, when all around the world people tried to take images of what the eye could not fully see such as the lunar terrain. Muybridge inaugurated a technique to freeze physical motion, a device comprised of twelve cameras, twenty-four inches apart set on Stanford’s 8,000-acre estate in Palo Alto. The cameras went off at 1/1,000 of a second, triggered by the horse galloping on the track. On the third day, he got the adjustment right, proving that “unsupported transit” did in fact take place. It took him until 1878 to create a more refined system and revisit the Palo Alto track.49 We focus on what would come out of this: Muybridge published his project Animal Locomotion (1872–85) to show the other physical movements that human vision cannot capture, which led to the birth of motion pictures. Yet we may forget what it conveyed—wonder through the mysterious act of sight was all around.50

Astonishment was bi-directional. People could lose themselves in both “minuteness” and “vastness.”51 The act of looking through a microscope could “lay bare a land of enchantments” and offer “revelations” that were “astounding.”52 The turn-of-the-century invention of the X-ray (a discovery, too, based on an accident taken as a route to a new possibility) was seen as a “new light, before which flesh, wood, aluminum, paper, and leather became as glass” which then many thought seemed “like some aged Arabian fiction.”53 Not only did scientific discoveries challenge the presumed accuracy of vision, but so did visual entertainments, from trompe l’oeil paintings to P. T. Barnum’s humbugs. This “diminished credibility of the seen world” around the turn of the twentieth century placed greater value on what cannot be glimpsed.54

The mechanics of how we see and remember when we are moved is one way that we move forward out of near ruin. Douglass was describing, as he saw it, our pictorial process of creating reality.

It is as true of vision as it is of justice—distorted, flat, horizontal worlds become more full when we accept that the limit of vision is the way we see unfolding, infinite depth. Painted and printed images used to be just flat bands of color until the invention of perspectival construction and with it, the vanishing point—the void, nothing, the start of infinite possibility.55 Moving toward a reality that is just, collectively and for each of us individually, comes from a similar engagement with an inbuilt failure. A fuller vision comes from our ability to recognize the fallibility in our current and past forms of sight.

When I visited Douglass’s estate high on a hill in Anacostia, overlooking the Capitol building, I saw that his irregularly shaped study, where he wrote speeches and correspondence, was angled to face three things at once—glass-paneled bookshelves, a wall of pictures and photographs, and a window with a view of pure expanse. There are homes, and there are homes. Douglass’s residence in Anacostia was a political act, not a retreat.56 His study has a curious tripartite vantage. It was off the parlor next to the main entrance without a division: there was no door. The arrangement of his study displayed his life lived with those powers—of oratory, of pictures, and through the window, a new imagined world. Behind his home, in view from his study, was a cabin—a windowless, one-room brick house, only ten by twelve feet—that he had built to replicate the slave cabin where he was born. Out on the house’s hilltop front lawn, he could face the arc of his own unprecedented rise—to the right, a green expanse of Maryland where he was born enslaved, and to the left, Washington DC, where he became a man so prominent that a bill was introduced in the Senate for his body to lie in state in the Capitol upon his death.57

He had no doubt, he said, that his topic would need further exploration. “The influence of pictures” upon our thoughts “may some day, furnish a theme for those better able than I, to do it justice,” he said.58 It has since become a timeless idea, articulated by national leaders and sages in our age.

What we lose if we underestimate the power of an aesthetic act is not solely talent and freedom of expression, but the avenue to see up and out of failures that we didn’t even know we had. Aesthetic force is not merely a reflection of a feeling, luxury, or respite from life. The vision we conjure from the experience can serve as an indispensable way out from intractable paths.

What is the future of how we think about so-called failure, these dubious starts and unlikely transformations? This was the apt question that came from a friend, a photographer, as I was writing this book. We can answer it by finding ways to honor them, by not letting the path out of them stay hidden, by letting them be generative, even indispensable. Seeing the uncommon foundations of a rise is not merely a contrarian way of looking at the world. It has, in many cases, been the only way that we have created the one in which we are honored to live.