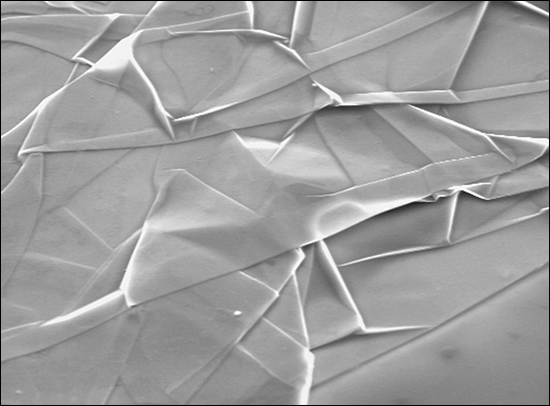

Graphene under the microscope. © Condensed Matter Physics Group, University of Manchester.

To know and then how not to know is the greatest puzzle of all . . . So much preparation for a few moments of innocence—of desperate play. To learn how to unlearn.

—PHILIP GUSTON1

“It says, ‘No entrance,’ but you just enter,” physicist Andre Geim told me as we walked with Ben Saunders at the G8 Innovation / DNA Summit in London when I was there to interview them onstage. Geim was talking about the graphite mines in the mountains where he often hikes—his preferred exploit when not researching in his lab at the University of Manchester, England. It was an echo. I had heard this from Geim’s younger colleague, Konstantin Novoselov, weeks earlier—his precise, pacific voice rising for the first time in our conversation: “The graphitic mines are completely unguarded. You can walk right in.” Their comments seemed less about hiking and more like unintended aphorisms, ones that could explain the insouciance behind their Nobel Prize–winning physics experiment: the first isolation of a two-dimensional object on the Earth.

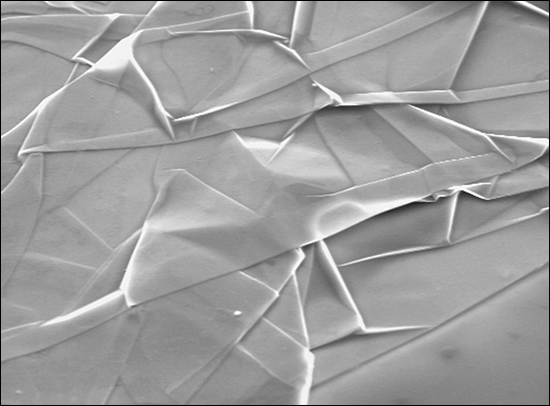

Graphene—as the two-dimensional honeycomb-shaped monolayer of carbon found in graphite is called—has turned out to be the thinnest, strongest, most conductive material to date on record.2 The material is finer than silk, two hundred times stronger than steel, and more inert than even gold. If we made a car out of graphene, it would be the lightest automobile in existence, but could also drive through walls. Graphene’s commercial applications, from solar cells to transistors, have made many think that it will replace silicon. This is a bonus on top of Novoselov and Geim’s main feat: identifying a phenomenon that has expanded what we know is possible in the world of physics itself.

Graphene under the microscope. © Condensed Matter Physics Group, University of Manchester.

The theory was that “Flatland” was a fantasy, just a whimsical invention from author Edwin A. Abbott’s mind.3 Physicists had long thought that objects with length, width, and no depth—meaning that electrons only move on a one-dimensional plane—could not thrive in a three-dimensional world. “It was assumed that they couldn’t exist,” Geim said, until the two physicists went about finding it by systematically abandoning their expertise.4 A paradox of innovation and mastery is that breakthroughs often occur when you start down a road, but wander off for a ways and pretend as if you have just begun.

Geim knows that, to most, his journey sounds unlikely.

“I tell people if you want to win a Nobel, first get an Ig Nobel,” Geim said, deadpan to the laughing audience in London, cued to his sardonic wit. Perhaps the audience knew that Geim is the only scientist to win both a Nobel Prize and Ig Nobel Prize, the reputation-denting award given to scientists for experiments so outlandish that they “first make people laugh, and then make them think.”5 Other Ig Nobel–winning experiments have included an award in chemistry for a wasabi-made alarm clock designed to rouse a sleeping person in an emergency, two prizes in psychology for the study of “why, in everyday life, people sigh,” an economics prize for finding that financial strain is a risk indicator for “destructive periodontal disease,” and a peace prize “for confirming the widely held belief that swearing relieves pain.”6 Witty, ridiculous, and slyly illuminating, the preeminent journal Nature has called the prominent prize announcements organized by the magazine Annals of Improbable Research, “arguably the highlight of the scientific calendar.”7

Geim won the auspicious Ig Nobel in Physics in 2000, ten years before winning the Nobel Prize, for levitating a live frog with magnets.

Geim is proud of his Ig Nobel, he said in his Nobel interview. “In my experience, if people don’t have a sense of humour, they are usually not very good scientists either,” he reasoned.8 The image of the flying frog had already made the rounds after its publication in the April 1997 issue of Physics World, what many considered just an April Fool’s Day prank.9 Geim didn’t care. Most thought that water’s magnetism, billions of times weaker than iron, was not strong enough to counter gravity, but the demonstration showed its true force. He had access to some of the strongest electromagnets around when he was working at the Radboud University Nijmegen’s High Field Magnet Laboratory in the Netherlands, where he held his first post as professor. The magnets consumed so much power that the lab only operated them at night, when costs were lower.10 Geim became curious about magnetism when he didn’t have the resources to continue his past experiments. If “magnetic water” did exist, he thought he would stand the best chance of demonstrating it with this device.

Frog levitated in the stable region. In M. V. Berry and A. K. Geim, “Of flying frogs and levitrons,” European Journal of Physics 18 (June 1997), 312. © IOP Publishing Ltd and European Physical Society. Reproduced by permission of IOP Publishing. All rights reserved.

On a Friday evening, he set the electromagnet to maximum power, then poured water straight into the expensive machine. He still can’t remember why he “behaved so ‘unprofessionally,’ ” but through it he saw how descending water “got stuck” within the vertical bore. Balls of water started floating. They were levitating. He had discovered that a seemingly “feeble magnetic response of water” could act against Earth’s gravitational force.

He dropped in all kinds of items containing water—strawberries, tomatoes, anything that would fit—until his lab colleagues, which include his wife, vortex physicist expert Irina Grigorieva, suggested that they levitate an amphibian to emphasize that there is truly diamagnetic force in everything. The frog was a better choice than other animals they considered—lizards, spiders, and even a hamster (too big).11 The frog may have been too attractive. The discovery made it into so many science textbooks that some mainly know Geim for the flying frog. The popular image also sparked some odd curiosity. A man who claimed to be a pastor from a church in southwest England wrote to Geim asking “very strange questions” about how to acquire his levitation machine and whether it could be concealed under the floor and not interfere with the sound of an organ, “So you can imagine what the application of this experiment would be!” Geim said.12

Many of his colleagues warned him that the award might damage his reputation, given its public nature (which is why awardees are given a few weeks to consider whether to accept their Ig Nobel). The raucous prize ceremony, complete with skits and roasts, takes place in a 1,000-person auditorium. Geim asked his colleague, Michael Berry, to accept it with him.

“He often complains that I used him as a fig leaf . . . ah, or whatever,” Geim said. He let out an incredulous laugh, then he stopped as if catching himself, his face turning slightly red, leaning forward in his chair, as he recalled it over a decade later.13 It wasn’t a self-deprecating aside about a humble detour. It was part of the direct route he and Novoselov took to isolate graphene itself.

The two acclaimed physicists have acquired the non-expert’s advantage through what Geim calls “Friday Night Experiments.” On these occasions, their lab works on the “crazy things that probably won’t pan out at all,” Novoselov told me, “but if they do, it would be really surprising,” and could constitute a major breakthrough.14 From the start of Geim’s career, he has devoted 10 percent of his lab time to this kind of research. It was this unique method that first attracted Novoselov to Geim’s lab in Holland when he was just a doctoral student. In 2010 when the two men won the Nobel Prize in Physics, Novoselov was thirty-six, the youngest in thirty years to win the award in that category.15 Just before the award-winning experiments, Novoselov had completed his research but hadn’t yet filed the paperwork to officially receive his PhD.

The Friday Night Experiments (FNEs), safe havens for their laboratory, are often so outlandish that they try to limit how long someone works on them—usually just a few months, so as not to hurt the careers of the lab’s postdoctoral fellows, undergraduates, or graduate students.

Geim’s perspective, blunt as you like, is that it’s “better to be wrong than be boring,” so he lets those working on the FNEs stay free enough to take risks and, inevitably, fail.16 This means that the FNEs are, unsurprisingly, unfunded. Due to their nature, they have to be. They are times when “we’re entering into someone else’s territory, to be frank, and questioning things people who work in that area never bother to ask.”

The physicists have become known for the unlikely breakthroughs that have come from these trials. Out of the two dozen or so attempted Friday Night Experiments, many have been near wins, such as one attempting to find the “heartbeats” of unique yeast cells, in which they detected no pulse or electrical signals, but noticed that when threatened, yeast emitted what the physicists jokingly called “the last fart of a living cell.” That is, when the cells were treated with excess alcohol, the sensor recorded a large voltage spike as if releasing a “last gasp.”17 Three FNEs have been hits, a success rate of 12.5 percent. The flying frog and the illustration of diamagnetism was the first. The second was the creation of gecko tape, the eponymously titled adhesive that mimics the clinging ability of the gecko’s hairy feet.

The third FNE hit was the Nobel Prize–winning isolation of graphene.

Friday Night Experiments are a way to live out the wisdom of the deliberate amateur.

“The biggest adventure is to move into an area in which you are not an expert,” Geim believes. “Sometimes I joke that I am not interested in doing re-search, only search,” he has said about the “unusual” overall career philosophy both men use to “graze shallow.” They stay in a field for five years, do some good work, and then get out.18 The inventiveness and sheer fun of it all can make it look like they’re not “doing science in the eyes of other people.”19 Shelving experience to remain open to new possibilities can make an expert look elementary. Yet the gifts from assuming this posture on the unfinished path of mastery can come no other way.

Geim and Novoselov found graphene hiding out in the graphite from an ordinary pencil. They isolated it with a tool that seemed even more rudimentary—a piece of Scotch tape. The physicists had never worked with carbon before. Their team worked long hours to familiarize themselves with the literature. Yet too much reading and research before experimentation can be “truly detrimental,” Geim believes. So they were careful not to read so much as to read themselves right out of their own ideas.20 Concepts are patchworks like centos, an aggregate of ideas from others over time. Graze too much before a new project or experiment and you may conclude that it has all been done.

The graphene FNE began when Geim asked Da Jiang, a doctoral student from China, to polish a piece of graphite an inch across and a few millimeters thick down to ten microns using a specialized machine for an experiment about transistors. Due to their language barrier, and Geim giving him the tougher form of graphite, Da polished the graphite down to “dust,” but not the ultimate thinness Geim wanted.21

The team salvaged the next step with a lateral move. Their lab also used graphite with scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) experiments, preparing it with adhesive rips to give it a clean, uncontaminated surface. “I knew about the process; it has been used for decades,” Novoselov told me, but now, with a low-temperature STM in the lab, he saw up close how they could just discard the Scotch tape after cleaning the samples.

“We took it out of the trash and just used it,” Novoselov said.22 The flakes of graphite on the tape from the waste bin were finer and thinner than what Da had found using the fancy machine. They weren’t one layer thick, an achievement that came with successively ripping them with the Scotch tape, but they were closer than any recorded attempt.

The act of writing on a blank page shows how easily graphite, made up of carbon, can be shaved. To write in pencil means putting enough pressure on the tip of graphite such that it peels off onto the paper, leaving a trail of gray—imperceptibly small layers of carbon. Attach graphite to adhesive and it will cleave. Over time, Novoselov perfected a method of using the tape to get the graphite down to one micron thick, pressing it on the graphite and ripping them apart. Their five-, sometimes six-person team then toiled for a year of intensive experiments done during fourteen-hour workdays to measure the monolayer of carbon. They also swapped the adhesive for Japanese Nitto tape, “probably because the whole process is so simple and cheap we wanted to fancy it up a little and use this blue tape.”23 Yet “the method is called the ‘Scotch tape technique.’ I fought against this name,” Geim said, “but lost.”24

Prior to this discovery, the charge carrier in all known atoms was thought to move through materials like billiard balls knocking into one another, but in graphene atoms the charge carrier mimics massless photons moving with a constant velocity—it appears to move at nearly 1/300th the speed of light. Take a monolayer of carbons out of that three-dimensional home in graphite with repeated Scotch tape rips and it exhibits a list of traits that, in concert, seem impossible. The two men would never call it a “discovery,” as much as non-specialists describe their feat that way. It was there all the while. “We came in one morning with nothing in our hands but a piece of graphite and within a few hours had a device that gave us a non-trivial result.”25 It may have seemed too simple.

The team submitted a paper summarizing their findings to Nature. The journal rejected it, such a common fate for historically path-breaking ideas that it could signal an unintended compliment. One of Nature’s anonymous referees responded that it was interesting but they would only publish it if the team “measured this, that, and the other thing in addition, and then maybe they’d consider it for publication,” Novoselov recalled, skimming over the details.26 The journal again spurned their resubmitted article. One referee said it did “not constitute a sufficient scientific advance,” Geim said in his Nobel Prize speech.27 Science magazine later published an even more polished version.28 The physicists’ second paper on the topic did appear in Nature.

“People probably didn’t believe that what we had was one-atom thick,” Novoselov told me. “It takes a lot of courage from the journal’s editor and the referees to put a paper of this proportion through. And at the time, even we didn’t understand what the implications might be. We didn’t even understand fully how many other people had been working on carbon science. But to this day, I’m not really sure why it was rejected.” He said it in a patient voice that held the symphonic contrasts of his own process. Some phrases were straightforward and clear. Others bolted through the phone with the poetry of knowledge crystallized into wisdom.

Their process is so well-known that Geim’s colleagues often ask if he’ll “move on” now that they’ve isolated graphene and created a new field of research in custom-designed materials made from two-dimensional objects. They “hope I’ll leave the field to them. No chance, guys!” he teased. “You’ll have to cope with my sarcastic jokes for longer” as he puts “more stakes in the ground” around what has now become an enormous research area, not the tumbleweeds it was at the start of their experiment.29 By stakes, though, he doesn’t mean filing a patent for the material.30

Geim wants to continue the adventure with “exploratory detours” and lateral steps always “away from the stampede.”31 He likens himself to a gold-miner character from a Jack London novel, trying to carry stones through a mountain pass to mark their terrain, a subarea in graphene research.32 Once he has, then he’ll find the next open plain on which to chart a new path.

An ever-onward almost is part of mastery, on the field, in the studio, and in the lab. The wisdom of the deliberate amateur is part of how we endure. Maintaining proficiency is best kept by finding ways to periodically give it up.

It is an old idea for artists, seen in the freedom that comes in a late style or the Zen concept of “beginner’s mind,” a shift in perspective that comes from trying to see things anew after gaining sufficient expertise.33 “As you grow older, every book becomes a little more difficult,” author Erskine Caldwell told The Paris Review about the process of writing, not just “because you’re more critical of what you’re doing,” but because “you reach the point where you know something is wrong but you’re incapable of making it any better.”34 Choreographer Twyla Tharp also used the technique. “Experience . . . is what gets you through the door. But experience also closes the door,” she said. “You tend to rely on that memory and stick with what has worked before. You don’t try anything anew.”35 Without off-road exploration, we have little way of figuring it out.

The amateur’s “useful wonder” is what the expert may not realize she has left behind.36 Psychologists call the unintended routine that comes with expertise the Einstellung effect. It is the cost of success: The bias that creeps in without our notice and can block us from seeing how to do things any other way.37 Deliberate amateurs are not trying to follow an apprentice’s schedule—learn the trade, climb the guild’s rungs, train another.

An amateur is unlike the novice bound by lack of experience and the expert trapped by having too much. Driven by impulse and desire, the amateur stays in the place of a “constant now,” seeing possibilities to which the expert is blind and which the apprentice may not yet discern. It can lead to playing like there’s “no birth certificate on your notes,” as Ornette Coleman once said about a trumpeter’s sound. It keeps us in the spirit of discovery.38

The term amateur is now pejorative: to lack in skill or knowledge, to be a dilettante, dabbler, fancier, or hobbyist—all conceptual flirts. Yet centuries ago, the word amateur wasn’t meant to disparage. It described a person undertaking an activity for sheer pleasure, not solely pursuing a goal for the sake of their profession. The French amateur is from the Latin amator—a lover, a devotee, a person who adores a particular endeavor.

An amateur’s adventure is an embodied feeling of being rapt, utterly absorbed. We sense it after reaching a state of exhaustion, switching tasks to something that has our interest, and feeling refueled, our endurance enhanced by authentic passion. For a moment, we are out of time.39 It can be the bodily suspension that let Geim pour water down a machine’s bore and not be able to explain what possessed him.

German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer and writer Ludwig Börne both made the case for periodically cultivating this approach. This was an age when arguing for originality had been controversial for centuries. (The term original was then a veiled synonym for “crazy,” unique in an unenviable way, until René Descartes shifted its valence).40 Börne argued for “the art of making oneself ignorant” in his controversial 1823 essay, “How to Become an Original Writer in Three Days.” Inherited knowledge, he said, was like some “ancient manuscripts where one must scrape away the boring disputes of would-be Church Fathers and the ranting of inflamed monks to catch a glimpse of the Roman classic lying beneath.”41 Schopenhauer developed Börne’s idea when he called for an “intellectual Sabbath” from constantly being on “the playground of others’ thoughts.” Worried that “his age would ‘read itself stupid,’ ” and no longer be able to generate novel ideas, he outlined his logic with an analogy about riding versus walking: If a person only rides and never walks, she will soon lose the ability to walk herself anywhere.42 Follow someone else’s route too often and soon you lose the ability to map out your own.

Besides, you can’t stay interested in your work if “from your scientific cradle to your scientific coffin, you just go along the straight railway line,” Geim has said often.43

Yet few cultivate this method as a strategy.

“You always can be considered as a fool,” Geim said, “inventing the wheel, investing your time into something, which might turn out like a blip.”44 It can turn a walk into a wander. Geim described how hard it was to switch subjects, moving from semiconductor physics to superconductivity. “I went to those conferences as a beginner with having a couple of already prestigious papers, being an associate professor. People looked at me [and said], ‘Who is this materials postdoc? What is he doing?’ Because I came from a completely different community . . . It’s not secure. You’re moving in the unknown waters which are not only scientifically unknown but . . . psychologically.”45 The approach means moving forward by backpedaling, running to get up to speed, leaping, then scanning the field midair to find out if you’re wasting your time.

This agility takes an inordinate amount of “courage,” Geim said. “I suppose,” he said, that is where “play comes in.”46 Playfulness lets us withstand enormous uncertainty: The deliberate amateur knows no other way.

“I want to start by discussing the subject of play,” said Adam Smith, the editorial director of Nobel Media, who conducted Geim and Novoselov’s official interview before the prize ceremony. “People often view science as a very serious exploit, but it’s really quite playful, and you in particular keep play at the forefront of your research activities. Can you tell me how play figures in your research?”

It was a reasonable opening question. The same Nobel interviewer had posed the question over the phone a slightly different way two months before. “I guess we could call it the ‘Lego Doctrine,’ ” Geim then said about his philosophy, and described how we build anew based on what “Lego pieces” we have, from “facilities” to “random knowledge.”47 If you tinker enough, if you’re curious and industrious enough, he said, “You don’t need to be in a Harvard or Cambridge, in one of the universities which collect the smartest people and the best equipment. You can be in the second- or even third-rated universities in terms of facilities and, whatever, prestige, but you still can do something amazing . . . without being at the best place at the best time.”48

Yet this time, Geim looked down, entwined his fingers, pursed his lips, and looked up at the ceiling. Novoselov started in. “They teach you a lot about physics in the University, but they don’t teach you how to do science.” Any process that “promotes the freedom of mind” is productive.49

As he concluded, Geim was still gazing upward. To talk about play, Smith had to prod.

“And you, Professor Geim?”

He looked to be mid-thought. He is, for all of his wicked humor, serious, even intimidating. The majority of Geim’s experiments require extreme focus and care. On the day when he was notified about the Nobel, he had plans to write a paper and answer e-mails and “muddle on as before,” but “the Nobel Prize interrupted my work,” he said. “I’m not sure that it’s a useful interruption, okay. Certainly it’s a pleasant one.”50 His Nobel Prize Banquet speech was a reminder about the danger of blurring the line between “opinion” and “evidence.”51 Novoselov values Geim’s industriousness and frankness. “It’s a great comfort to have someone nearby who is smarter than you are. And Andre is direct enough to also say when he thinks something is bullshit,” said Novoselov, even if it’s just with a facial reaction. “It won’t take much to get a clear answer from him.”

But when Geim was asked about the centrality of so-called play to innovation in the formality of the Laureate interview, he deliberated a long time. I would later ask him why he was so reluctant to speak.

When a musician says that someone can play, it means they are skilled, responsive, and nimble; the person knows how to harmonize or offer dissonance when it’s right. The musician can play like Esperanza Spalding, with her hands on the bass and her voice running in a different direction altogether. But it is also the emphasis on the word. Musicians often say it with a downbeat at the end, stretched out like a bass bow, as if the word is as heavy as the talent they’ve described. Their tone conveys that this skill is serious. We hear the heft inherent in the creative act of play when, for example, author Toni Morrison says that an idea for a book never comes to her “in a flash,” but is “a sustained thing I have to play with.”52 Yet outside of the creative process, play is a term that can hurt the concept it names. It’s nearly axiomatic that play is considered the opposite of much that we value—heft and thoroughness. Use it as a noun, an adverb, or a verb, and most of these words will only skim the surface of what play means, and what it can lead to.

We recalled play’s importance when Antanas Mockus resigned as president of the National University of Colombia, successfully ran for mayor of Bogotá in 1995 and again in 2001, and became widely credited for transforming one of the world’s most chaotic, crime-ridden cities with tactics so playful, so humorous that to some they looked foolish: one policy called for mimes to replace the “notoriously bribable” traffic police. With faces painted white or blue, some dressed in bowties, black pencil on their eyes and eyebrows to exaggerate expression, the mimes would stand at intersections and on streets mocking bad behavior and praising good behavior from pedestrians and drivers. Mockus’s theory was that play could help, since people are often more afraid of ridicule than being fined. During his tenure, traffic fatalities dropped by over 50 percent. The homicide rate also decreased by 70 percent. The program was so successful that Mockus fired 3,200 traffic cops. The hundreds of traffic officers that remained were trained as mimes.

“I said to myself, we’re six million inhabitants. Those games can’t transform behavior,” said Rocio Londoño, director of culture and arts in Bogotá, reflecting on Mockus’s work.53 Yet the spritelike Mockus continued to employ his policies at every turn. To advocate for water conservation, the heavily bearded mayor filmed a (largely cropped) commercial of himself in the shower, turning off the water as he lathered. Water conservation in the city improved by 40 percent during his administration; he was able to provide drinking water to all homes. (Only 79 percent had water in their homes before his tenure.)

Mockus was a deliberate amateur, a university president who intentionally chose a new course. During his two nonconsecutive terms, his policies aimed at fixing the disparity between culture, morality, and the law. Yet, as his colleagues pointed out, he wasn’t an expert in political theory. He ran as a true skeptic of traditional politics, the first Independent mayor, with no favors to bind him. Months before his election, he was known only as a mathematician and philosopher. Not yet married to Adriana Córdoba, he ran his 1994 campaign from the house where he lived with his mother, Nijolé, a Lithuanian-born sculptor who disapproved of his entrance into politics. Journalists would come to interview him. His mother would ask the journalists to get out of her house. During his campaign, he literally ran around the city streets, cleaning its “visual pollution” in a self-styled yellow and red “Supercitizen” full-body leotard. The news site La Silla Vacía said that Mockus was most like surrealist Salvador Dalí in his relationship to the public: “Even if they don’t understand his words, they understand his message.” In the country that inspired the magical realism of Gabriel García Márquez, political analysts resorted to artistic analogies to explain Mockus’s phenomena in Colombia—the staggering shifts that came through the perception shift of radical play.

We seem to know the centrality of play as we speak through a language of dexterous hands. The symbol for support and approval is a thumbs-up. When we understand a concept, we often say that we grasp it. When a circumstance is under control, we have a grip on it. Even foundational contracts can be signed by a handshake agreement. A gesture or event that moves us is touching. We say that we’re staying in touch even though we might have no physical contact at all, but communicate regularly. When a show’s script needs improvement, it gets a punch up. “The hand is in search of a brain, the brain is in search of a hand, and play is the medium by which those two are linked in the best way,” Stuart Brown, founder of The National Institute for Play, summarized.54

Perhaps we underestimate its importance because we forget what physical anthropologists know: When we suppress play, danger is often close at hand. Of all the species, humans are the most neo-tenous; we have great potential to stay supple, flexible, and to retain qualities found in children throughout our lives, one of which is the ability to play. Brown understands its importance from his work in internal medicine, psychiatry, and clinical research. He saw it in a gruesome study on the common theme of play deprivation in homicidal males. After years of taking play histories of individuals, Brown has found that our earliest memories connected to joy and play alter the trajectories of our lives as adults.55

Play’s importance is also evident in early childhood development and learning. For every fifteen minutes of play, children tend to use a third of that time engaged in learning about mathematical, spatial, and architectural principles. One of my favorite examples comes from a study from the journal Cognition, run by MIT professor Laura Schulz, with this setup: In the first group, an experimenter would take a toy with four tubes to a group of four-year-olds, and in one case she would act surprised when she pulled a tube and it squeaked, and then leave them with the toy. Another group of four-year-olds received the same toy, but through directed teaching—“I’m going to show you how this toy works. Watch this!” she said excitedly, and then made the tube squeak. Systematically, when both groups of children were left alone to play with the toy, all made it squeak, but the first group engaged with it for longer than the second group. The group introduced to the toy through play also found out that it had “ ‘hidden features” that the experimenter hadn’t hinted at, like the mirror hidden in one of the tubes. The group taught about the toy never discovered all that it could do. Their curiosity was dampened. The research is becoming more and more clear about this counterintuitive fact: directed teaching is important, but learning that comes from play and spontaneous discovery is critical. Endurance is best sustained through periodic play.

“Kids are born scientists,” astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson believes. “They’re born probing the natural world that surrounds them. They’ll lift up a rock . . . They’ll experiment with breakable things in your house. It might mean they break a dish someday, because they’re experimenting with how dishes roll down the corridor . . . So you buy a new dish. And you say, ‘Well, that can be costly.’ But as Derek Bok, former president of Harvard, once said, ‘If you think education is costly, look at the cost of ignorance.’ ”56 Just as C. P. Snow and others argued for the conceptual reunion of art and science, Tyson, Beau Lotto, and others have made the same case for some conceptual blending between what we see as science, discovery, and play, and what constitutes innovation in any field.

The trouble is that the perspective-altering gift of play remains associated with children. “That’s been the biggest barrier—people see it as the opposite of work, as something childlike,” said Ivy Ross, a pioneering designer and marketing executive who became known for her innovation at firms from Mattel to the Gap by creating new environments that prioritized play.57 “And that’s why it’s really a hard thing for people to accept. But play is actually the opposite of depression, since depression is being numb to possibilities.”

To work around this, Ross created Project Platypus at Mattel’s El Segundo, California, headquarters. The space was informal. She rotated in a team of twelve, stripped of their titles and given positions as mobile as their desks on wheels. They could work with whomever they wanted, however they wanted. Aside from a room for private calls and a room for “sound baths”—a space with chairs with inbuilt speakers, tipped at the angle of an astronaut’s shuttle launch chair, that played those rare binaural frequencies meant to stimulate both hemispheres of the brain—their workspace was lined with carpets that looked like grass. It resembled a Montessori environment, with stimuli to satisfy every self-initiated interest: games and even rubber rockets to shoot to give the mind a break. There was no set schedule; the weeks were filled with “mental grazing,” the team filling themselves with new ideas, images, and concepts that they knew little about.58 “Sometimes the ideas gelled, sometimes it wasn’t until week seven, but it never disappointed me,” Ross said about Project Platypus. They always got more innovative work done than ever before. It was so creative it was fertile. People joked that it was the secret key to pregnancy. After twelve weeks with Ross, women who had been trying to conceive often left somewhere in their first trimester.

“Innovation is an outcome. Play is a state of mind. Innovation is often what we get when we play,” Ross believes.

A constellation of voices has begun to argue for the importance of permitting an adventurous approach into the process of innovative, serious work. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL) considers play so critical for its engineers’ performance that it asks applicants about their hobbies as children. In consultation with Frank Wilson, a neurologist focused on the coevolution of the hand and brain, and Nate Johnson, a mechanic in Long Beach, JPL found that younger engineers were not as good at mechanical problem solving as their retiring engineers. The kind of play that Wilson championed happened so infrequently that NASA experts were then not as comfortable using their hands.59 JPL then changed its policy to ask candidates about how much they played in their childhood, no matter how stellar their academic pedigree.60

Play spaces don’t necessarily need anything commodious. The paracosms children often create are a hallmark of innovation of another kind of play: the abstract thinking that produces extended, private meta-worlds. Apparently, MacArthur Fellow “genius” grant winners engage in these magnum daydreams when they are young at a rate twice as high as that found in a sample set of college students. Robert Root-Bernstein of Michigan State University, who pioneered the study that produced this finding with his wife and colleague, Michele, is a MacArthur Fellow recipient himself.61

We create because we imagine. Pioneering French polymath Henri Poincaré, who, like Geim, moved from field to field within mathematics and physics, describes how ideas act like objects in motion: “I could almost feel them jostling one another, until two of them coalesced [s’accroachassent], so to speak, to form a stable combination.”62 Perceptions of innovation in science, the arts, or in exploration of any kind can block our view of what is often going on—the constant suspension and multi-sensation of cognitive and physical play.

The slipstream between working and work generated from imagining is also why Novoselov told me that it was impossible to set a true start date for any single experiment. When I asked him when the FNE for graphene began, he mentioned that it began in internal ways—while going to sleep, in the shower—such that making a true start date is inevitably inaccurate.

Yet in the context of scientific research, play may never be the right word, at least not publicly.

What Geim wanted, he would later reveal, was a new term, a “slightly different manner of speech,” to define what we really mean by play: “curiosity-driven research.”63 He would prefer to call it “adventure.”64 His Nobel Prize Lecture is titled, after all, a “Random Walk to Graphene.” That was how he would describe the journey, a hand-connected experiment that is, in fact, not research, but a search.

A process akin to Friday Night Experiments is at work in some of the best science labs in the country, it seems, as Kevin Dunbar discusses his research in four prominent molecular biology labs over the course of a year. Dunbar, now at the University of Maryland, has spent nearly his entire career quantifying just how valuable it is to take mistakes seriously in the lab and how we can overcome the blind spots to them.

“We really know virtually nothing about the scientific process, about how scientists think and reason,” he said. After fifteen years of total access to four prominent biochemistry labs, following the scientists at meetings, looking at their lab journals, grants and tests, and watching them interact (what he has termed an “in vivo” research method), Dunbar observed that their experiments were failing 40 to 75 percent of the time, but the best scientists were able to follow up on their unexpected findings. He has found that the most productive labs were the ones where nonspecialist scientists were part of the results review process.65 In labs where scientists all had the same types of expertise, figuring out what was going wrong was slow and inefficient.66 When someone thinks they understand something, the mind edits reality so efficiently that errors can be hard to perceive, but when someone observes a scenario that they are unfamiliar with, a part of the brain operates inefficiently, giving us time to see outliers and consider their significance.

Factors such as job security help determine who ultimately sets out to follow the path of the deliberate amateur. Graduate students and postdocs were often the least motivated to go through the laborious process of following up on each failure since “they have short-term goals,” Dunbar said. “They want to get a job when they’re done and have a good publication, but tenured professors, who have relatively secure career futures, liked the unexpected findings.” The more senior the researchers were, he found, the more they could afford to “play.”67

“How many scientific revolutions have been missed because their potential inaugurators disregarded the whimsical, the incidental, the inconvenient inside the laboratory?”68 Dunbar offers an answer. The freedom that comes from the context of FNEs can assist the resistance.69

These late-night adventures give permission to release ourselves from what can stymie invention—“wrongness,” as author Kathryn Schulz calls it. “Recognizing our errors is such a strange experience,” she writes: not only is it an unhoned, largely ignored part of our internal lives, but when we do find ourselves confronting our own error “we suddenly find ourselves at odds with ourselves.”70 This feeling of wrongness is the sense of recognition that Aristotle described in the Poetics, the moment when a character sees his own error in a Greek tragedy. “Error, in that moment, is less an intellectual problem than an existential one—a crisis not in what we know, but in who we are.”

Some environments never permit such havens or Friday Night Experiments, and for this we have vacations; time to spend away from our routine to relax and often pursue a passion project. It is the same principle behind the increased efficacy we see when we work with brief intervals of rest during the day.71 Yet we often see vacations as we do play: a period at odds with productivity when it actually enhances it.

The idea of the scientific process as a search, an adventure, is more than a metaphor; Geim has found that research is both his labor and his “hobby.” A vacation for him is likely to be a hike or a short walk. I spoke with Geim in London after our panel with Ben Saunders, as both men relaxed in the greenroom of the G8 Innovation / DNA Summit. The physicist was interested in talking with the polar explorer and in getting advice from him. He sensed that their exploits were similar.

“I have these sideways pursuits,” he said to Saunders about his explorations when we were offstage, “and because I’ll likely never meet another man like you again I’d like to know, what is the most difficult thing you find out in the Arctic? What is it? The perseverance, the stamina—this I know you have, okay—the isolation. It can’t be because you talk to your teammates on the phone. It is . . . what?”

“It’s being able to withstand it,” Saunders said. “Courage,” he added, and the surprising ways that we find it within. Geim nodded, looked down, and smiled.

Geim then told me why he had been reluctant to speak about play in his official Nobel interview. He wanted to emphasize the paradox of play. Whimsy is what permits us to endure the gravity of the conditions required for innovation (and exploration). I listened as Saunders talked about his last preparations for the Arctic, and then as Geim laughed, recounting tales of his falls down mountain crevasses. It was as if they had met in the common space between their endeavors. “To strive, to seek, to find . . .”

Trammeled walkways that emerge on the grass and ground are called desire lines—intrepid paths stamped into the ground by the determined impulse of freedom. In the woods and in cities, these footpaths offer more efficient ways to get around than the urban planners have designed with paved streets. In Finland, urban planners often head to parks after snowfall to view how pedestrians would navigate if they followed their own desire.72 To follow these desire lines is “to respond to an invitation.”73 Someone had to be the first to tread. This is the kind of adventurous search, seeking out roads that, though hidden, are found on open ground, “waiting for our wits to grow sharper.”74

The graphite mines do lie unguarded. When the trade in graphite fell centuries ago, the mines opened again and the paths to them lay fallow. Hikers discovered them by following the desire lines up the mountainside. Novoselov saw them for himself, surrounded by the higher ranges like Scafell Pike, the tallest mountain in England, near the material’s excavation sites. Researching these graphite-lined paths is what he often does when not at work on the next stage of graphene—making custom materials built “layer by layer with atomic precision” that can have predetermined properties and functionality: “We can select one layer to be a sensor, one [could] be photosensitive, act as a solar cell, [and] another layer can act as a transistor.”75 Last I spoke to the physicists, they were able to make custom-designed materials ten microns thick.

The untold story of graphite brought Novoselov home to his lab—the material was originally found, sold, and mined from Britain’s Lake District, near his base in Manchester.76 The veins of the pockmarked mountains, near the wettest part of England, Seathwaite, hold graphite as a pure material, abundant and unmixed with other minerals. Once termed “wad” by locals, graphite was so easy to find that it could be “taken out in lumps sometimes as big as a man’s fist.”77 Lake District farmers used it to mark their sheep until the early eighteenth century, while during the Renaissance Flemish traders sold this English graphite to artists—it was perfect for gestural strokes.78 Graphite was also a valuable material for artillery and protected iron and steel from rust. For a period, an act of Parliament guarded the mines.79

Novoselov thinks graphite was used earlier than all of this evidence suggests. He has found graphite pencils and manuscripts that antedate the mines’ official history. The material was there all the while.

The entrances to the graphite mines are clearly visible, but only after first scaling its gateway peaks. Otherwise, they remain hidden in plain sight.

To play is a way of climbing and finding hidden mines without serious strain. Those who manage to suspend their disbelief see the threshold—horizontal and often dry—and enter.