Samuel F. B. Morse, First Telegraph Instrument, 1837.36 Division of Work and Industry, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

The stars we are given. The constellations we make.

—REBECCA SOLNIT

Driving up a New York State highway along the Hudson River to Locust Grove, the house designed for Samuel F. B. Morse, I was just shy of a bridge wall that had recently collapsed when I thought about the line between dogged pursuit and dysfunctional persistence, between knowing when to continue and when to quit and reassess.1 The difficulty we have in distinguishing between these differences results in the curious fact that somewhere in the world, roughly every thirty years, a major bridge collapses while it is still being erected or soon thereafter.2 When scientists Paul G. Sibly and Alastair Walker identified the thirty-year cycle, they found that it was not caused by the implementation of any new technology, or because of a lapse in an engineer’s rigorous structural analysis, a field with a history of documenting failures dating back to the time of Galileo. It occurred because when engineers are one professional generation removed from the inception of the foundational design, they tend to trust their models too much. If a proven template has no chance of going awry, it is only after an obvious breakdown that the painstaking process of anticipating glitches begins.3 The ongoing pattern of collapse occurs, in other words, because of the blind spot created by success.

Effective building—of bridges, of concepts, and ideas—comes from a more supple form of grit that knows when development needs to give way to discovery.

When Morse invented the telegraph, he constructed the first model out of cogs, clock springs, and more, and set it into a wooden frame—the abandoned canvas stretcher bars for a painting he would never complete. He longed to be an artist. For twenty-six years, he had worked to become a renowned painter. Then he took what he learned to pioneer the invention of the telegraph.

I wanted to speak with Angela Lee Duckworth about this nimble form of grit. Weeks earlier, as I walked straight down the hall to meet Duckworth in her office at the University of Pennsylvania, and she beat me to it. Casually dressed in a boat-necked striped shirt, pants, and flats, her jet-black hair pulled back in a mid-height ponytail, she was bounding out of her office heading toward me. She was welcoming, warm, and commanding. When she and I were finished talking after that first meeting, her students lined up like ducklings, waiting in the threshold of the open office door, waiting for me to gather my bags. I was in the Positive Psychology Center, which has produced some of the most path-breaking work in the country, and I was talking with the recent MacArthur-winning scholar who humbly knows the limits of what can be studied in the lab.

Her work began in the first few months of her graduate school research, when she and Martin Seligman, head of the Positive Psychology Center, kept thinking about one main question: What are the true barriers to achievement? There are three kinds, as they saw it. The first is adversity, something that happens effectively to you—things implode, break down, or catastrophe strikes. There is also failure, hardship for which you are largely responsible. Then there are plateaus, a more subtle form of stultification where there is no visible movement forward. There may be no progress for decades. During each scenario, the urge to give up is adaptive and reasonable. We need to have that impulse. Yet the urge to hold on could explain how we could sustain ability, capacity for hard labor, and zeal over time. They thought the missing variable was grit.

Duckworth is best known for her research on both self-control and grit—what her studies show is one of the most powerful predictors of achievement, especially in challenging contexts. She has examined grit in a variety of environments from Teach For America to the Scripps National Spelling Bee, and the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. The U.S. Military Academy was so intrigued with the importance of grit that in 2004 she was invited to challenge their “Whole Candidate Score”—a composite score based on GPA, SAT scores, class rank, leadership ability, and physical fitness—against her grit scale derived from a self-report assessment test, comprised of statements such as “I finish whatever I begin” and “new ideas and projects sometimes distract me from previous ones.” Which metric was a better longitudinal predictor of the cadets who would last past the grueling summer of Beast Barracks, the punishing training first-year cadets endure at West Point? Whole Candidate Scores were not at all related to the number of cadets who stayed in the program—cadets were equally likely to leave West Point if they were in the top or the bottom of that metric. Grit scores, however, were significant predictors of staying in the program. Grittier cadets were more likely to make it through the summer.4

What surprised Duckworth was that grit is not positively correlated with IQ. Grit is connected to how we respond to so-called failure, about whether we see it as a comment on our identity or merely as information that may help us improve.5

I wanted to see if she could help me with a riddle, which for now let’s call the riddle of Samuel Morse: how to cultivate grit and when to stop before it becomes dysfunctional persistence.

Grit is not just a simple elbow-grease term for rugged persistence. It is an often invisible display of endurance that lets you stay in an uncomfortable place, work hard to improve upon a given interest, and do it again and again. It is not just about resisting the “hourly temptations,” as Francis Galton would call them, but toiling “over years, even decades,” as Duckworth argues, and even without positive reinforcement.6 Unlike dysfunctional persistence, a flat-footed posture we ease into through the comfort of success, grit is focused moxie, aided by a sustained response in the face of adversity.

Grit and self-control are distinct. Self-control is momentary, exercised by controlling impulses that “bring pleasure in the moment but are immediately regretted,” Duckworth said.7 The most vivid example comes from psychologist Walter Mischel’s “marshmallow studies,” as they are often called, conducted in the late 1960s, about the predictive power of self-control and delayed gratification. “Do you want one marshmallow now or two marshmallows when I come back?” he had researchers ask each of the children. Some opted for the immediate rush of one treat, while others held out for more. Follow-up studies decades later showed that the trait of self-control endured, and was correlated with high achievement and life outcomes measured by metrics from SAT scores to educational attainment.8 The time scale is longer for grit.

For the decade before she studied grit, Duckworth looked like its unlikely pioneer. During high school at her family’s dinner table in their home in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, her father, a color chemist at DuPont, would ask Duckworth questions such as, “Was Einstein or Newton the greater physicist?” or “Who was the greatest artist who ever lived?” As a teenager, she had been developing this hypothesis that happiness was people’s main aim. She asked her father what he wanted out of life. “He said, ‘I want to be successful. I want to be accomplished,’ ” she recalled. “I pushed back on him and said, ‘Well, what you mean is that you want to be happy and being accomplished is what makes you happy.’ He said, ‘No, what I mean is that I want to be accomplished. I don’t care if I end up happy or not.’ ” Habits leading to achievement became a topic that would smolder throughout her life.

Her decade after college is one she summarizes as “how not to be gritty.”9 It is filled with stop-and-start jobs that all required different skills—teaching, speechwriting, and consulting. Then she decided to pursue a doctorate at the age of thirty-two and began studying the psychology of effort.10 One day she sat in her apartment “doing the hard, depressing math” that she would be “forty years old before I had a real job,” and thought about the humiliation of going back to her fifteen-year college reunion still a student. “I realized that working hard is not enough. I needed to work hard consistently on a given path to accomplish anything.”

“Angela was fast, about as fast mentally as it is possible for a human being to be,” said Martin Seligman.11 Yet getting her PhD meant curbing her tendencies to flit. She asked for help from her husband, a sustainable real-estate developer. He became her accountability partner to follow through on her decision to complete the degree. There were moments when he had to remind her of their pact, like the time when she complained and wanted to leave the program and go to medical school instead. “You can’t do everything,” he reminded her. “You have to pick a path. And you’ve picked a pretty good one.”

Duckworth gets up every day to study, research, and teach the psychology of achievement. “I don’t play an instrument; I don’t study the psychology of eating, for example, although that’s kind of cool,” she said before a rare pause in her rapid-fire speech style as she looked down and smiled. “I just get up and study the psychology of achievement and effort, why people exert effort and why they don’t.” In her corner office was some corroborating evidence—a dense pile of white papers stacked and splayed out on her L-shaped desk, on top of file cabinets, at skewed angles with a logic that suggests a personal stratagem, a large mission to achieve, and enough active energy to live it out. My bag was next to the only free space on the floor I could find.

Duckworth wants to understand the psychology of achievement, and not just for “talent at the very high end,” but how to cultivate talent that occurs “way further back in the distribution.” The conclusion that grit is a critical characteristic for achievement has impacted schools across the country.12 U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan invited Duckworth to give education policy recommendations; she has worked with charter and private schools like Riverdale Country School, a top-tier New York City private school in the Bronx led by Dominic Randolph, and she is focusing on the portfolio mechanism of grading, one common in creative environments.13 Her studies and ideas have also become integrated into the pedagogy at the New York City KIPP network of charter schools, where cofounder David Levin has noticed that the alumni who went on to excel in college were the grittiest.14

Given the centrality of coping with failure to cultivate grit, it is no surprise that Harvard University president Drew Gilpin Faust recently said that we need to make it safer to fail.15 “Harvard students are good at performing in areas in which they excel. Learning how to fail is against their understanding of themselves.” What book did Faust think that all incoming freshmen should read? Being Wrong: Adventures in the Margin of Error by Kathryn Schulz.16 In her baccalaureate address to seniors, she stood “dressed like a Puritan minister” in the pulpit of Memorial Church, encouraging them to take risks and pursue their Plan A, delivered with a statement of “Veritas” that few expect—to succeed, you have to learn how to handle failure first.17 Harvard has also initiated the Success-Failure Project, designed to help students cultivate resilience in the face of rejection and setbacks.

Christopher Merrill, director of the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa, a place that is “harder to get into than Harvard,” tells me that in every workshop he was ever in, the teacher always thought that someone shouldn’t be a writer. “But what they can’t tell is how much someone wants something,” he said, how much a person is willing to work and under what circumstances.18

“People ask me all the time, ‘Are kids in America working too hard?’ Yes, there are privileged kids who are over-programmed, but,” Duckworth said, her voice more firm, “I think in life, most people are giving up too early.” If we go by the studies, it is not talent, not even self-esteem, but effort that makes the difference in measurable forms of achievement. It leads to the surprising fact that self-esteem increased amongst American children in the 1990s from its 1980s and 1970s levels—a laudable trend, but measurable achievement has not improved along with it.19 Higher self-esteem without higher levels of achievement means “many American kids, particularly in the last couple of decades, can feel really good about themselves without being good at anything.”20

In one of our conversations, she told me about Finland’s development of sisu, a rough cognate for grit. Etymologically, sisu denotes a person’s viscera, their “intestines (sisucunda).” It is defined as “having guts,” intentional, stoic, constant bravery in the face of adversity.21 For Finns, sisu is a part of national culture, forged through their history of war with Russia and required by the harsh climate.22 In this Nordic country, pride is equated with endurance. When Finnish mountain climber Veikka Gustafsson ascended a peak in Antarctica, it was named Mount Sisu. The fortitude to withstand war and foreign occupations is lyrically heralded in the Finnish epic poem, The Kalevala.23 Even the saunas—two million, one for every three Finns in a country of approximately five and a half million—involve fortitude: A sauna roast is often followed by a nude plunge into the ice-cold Baltic Sea. If Iceland is happier than it has any right to be considering the hours the country spends plunged in darkness each year, Finland’s past circumstances, climate, and developed culture have turned it into one of the grittiest.

Finland’s educational system is also currently ranked first, ahead of South Korea, now at number two.24 The United States is midway down the list.25 In Finland, there is no after-school tutoring or training, no “miracle pedagogy” in the classrooms, where students are on a first-name basis with their teachers, all of whom have master’s degrees. There is also more “creative play.”26 Perhaps the tradition of sisu and play, I suspect, are part of the larger, unstated reason for its success.27

“Wouldn’t it be great if you heard people talking about how they were going to do something to build their grit?” Duckworth asked.

Gritty people often sound, says Duckworth, like one of her favorite actors, Will Smith. He once said, “The only thing that I see that is distinctly different about me is I’m not afraid to die on a treadmill. I will not be outworked. Period. You might have more talent than me, you might be smarter than me, you might be sexier than me; you might be all of those things—you got it on me in nine categories. But if we get on the treadmill together, there’s two things: You’re getting off first, or I’m gonna die. It’s really that simple, right? . . . You’re not going to outwork me.”28

They can even sound like James Watson, co-discoverer of the structure of DNA. “When I was a boy, I had to reconcile the fact that I didn’t have a good IQ, but I still wanted to do something important,” Watson told me, recalling the reasons for his path-breaking discoveries from his office at Cold Spring Harbor one July afternoon. “I knew it would take grit, no question about it,” he said. He remains gritty about his avocations, too. “I want one hour with Roger Federer,” the octogenarian scientist said, explaining that he had started to get serious about tennis in his fifties and sixties. He volleys with the same tennis racquet Federer does. “I want to see if I could get even just one point on him.”29

Gritty people also sound like Morse.

Morse stated his decades-long ambition in even more lofty terms: “To be among those who shall revive the splendor of the fifteenth century; to rival the genius of a Raphael, a Michael Angelo [sic], or a Titian; my ambition is to be enlisted in the constellation of genius now rising in this country.”30 By his early forties, Morse considered destroying every canvas on which he’d ever laid his brush. Encountering every imaginable type of criticism about his work, failing repeatedly to receive painting commissions, and unable to support himself and his family, he felt “jilted,” his ardor returned with dust.31

Yet Morse would go on to build the nation a network; an invented trace of dots and dashes that ultimately bridged the extent of the globe. The telegraph, from the Greek tele and graph (to write at a distance), “annihilated space and time.”32 Its unprecedented communication speed seemed to have “chained the very lightning of heaven.” Its “almost supernatural agency” as one newspaper said, astonished. It left people “wonder-stricken and confused.” News of the signing of the Declaration of Independence once took two weeks to travel on horse or by foot from Philadelphia to Virginia. With the telegraph, news moved within minutes. A circuit that controlled recording keys—a lever, a magnet, a stylus, and scrolling paper—would create its signal dots and dashes, lines fashioned by electric current. While it would take decades to finalize the code and the relay, this principle was correct from the start. An exemplar of Yankee ingenuity, the telegraph model on loan from the Smithsonian now sits in the Oval Office. Many considered “the lightning line,” as the telegraph was often called, to be “the greatest triumph of the human mind.”33

Kenneth Silverman’s biography of the painter and inventor has an appropriate title: Lightning Man: The Accursed Life of Samuel F. B. Morse.

Morse had achieved stature as cofounder and president of the National Academy of Design in New York helping to nurture American artistic identity during the post-revolutionary era, and as an associate of the American Academy of the Fine Arts, but couldn’t eke out a living with his “migratory wanderings” in New England, painting portraits for fifteen dollars per head when he could find the work. He settled his family in New Haven while he painted and slept in his New York City studio, concluding, “If I am to live in poverty it will be as well there as any where.” He received a few prestigious commissions. Exhibiting them put him in debt. After the painting career that Morse considered, largely, a failure and the personal catastrophes it later created for his family, there was a nearly two-decade-long trial to create a transatlantic telegraph model—one filled with setbacks, prohibitive debt, social defections, public controversies, and feuds. At the end of his life, he felt that he had endured enough to drive anyone “into exile or to the insane hospital or to the grave.”34

Sometime after 1832, in Washington Square—his lodgings at the University of the City of New York (now New York University), where he was the school’s first professor of Painting—he nailed the wooden backing of the canvas firmly to a table to hold the telegraph model together. The battery wires and the frame of the first device were to him “so rude,” so coarse, that apart from relatives and trusted students, “he was reluctant to have it seen.”35

Morse devised the idea on the ship Sully on his way back from a two-and-a-half-year trip spent in Europe to study painting. He splayed out his concept for electrical telegraphy on three pages of his pocket sketchbook, constructing its “system of signs and the apparatus” underneath a list of countries, what could have been a model for a listed message sent over his imagined telegraph wires that read: “War. Holland. Belgium. Alliance. France. England. Against. Russia. Prussia. Austria.”37

Samuel F. B. Morse, First Telegraph Instrument, 1837.36 Division of Work and Industry, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

In 1837, he applied for a patent for his model, having heard that Boston physician Dr. Charles Jackson might have done so first. Fear of a near win forced his hand.38

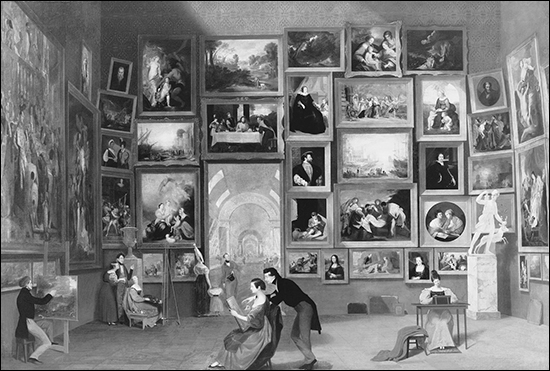

Morse would not live to see one of his paintings, completed just before quitting the profession to work on the telegraph, garner international acclaim. This was his six-feet by nine-feet canvas Gallery of the Louvre (1831–33), for which Morse replicated thirty-eight largely Italian masterpieces, including the Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci and multiple works by Titian, Veronese, Poussin, Rubens, and Claude Lorrain, piling them as he saw fit on the walls of the Louvre’s Salon Carré.39

Morse labored for fourteen months over this piece at the famed museum. He ventured outside during the cholera outbreak that took lives, maintaining such ascetic work habits that he “created a sensation in the Louvre,” with so many onlookers that he had “a little school of his own,” said author James Fenimore Cooper, America’s then-best-known novelist. Cooper would stop by the second floor of the Louvre to visit Morse nearly every day and egg him on, like an athletic fan in the stands: “Lay it on here, Samuel—more yellow—the nose is too short—the eye too small—damn it if I had been a painter what a picture I should have painted.”40

Samuel F. B. Morse, Gallery of the Louvre, 1831–33. Oil on canvas, 733/4 x 108 in. Daniel J. Terra Collection, 1992.51. Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago / Art Resource, NY.

In 1833, Morse’s painting failed to ignite public interest when it went on display in New York at the bookstore Carvill & Company on Broadway and Pine Street. The store charged twenty-five cents to see the work on display. The reviews were warm, but the public didn’t show. Financial valuation is hardly the same as artistic value, but the painting then sold for barely half of the asking price. “My profession . . . ,” he said, “exists on charity.”41 In 1982 the Terra Foundation for American Art purchased Morse’s Gallery of the Louvre for $3.25 million. It was a record for the sale of an early American painting at that time.42

Morse considered Gallery his chef d’oeuvre. The painting emblematizes a way of seeing that predates the modern age. It showed the once ritual space of the salon, where some large works were “skied,” or hung near the ceiling, before the gallery space would be reconsidered as the antiseptic white cube, where, as artist and critic Brian O’Doherty put it, even the body can feel like an intrusion.43

Morse’s eventual level of acclaim compared with his litany of failures seemed so improbable that the public speculated about his personal characteristics. Some thought it a wonder that he “succeeded at all, that he did not sink under the manifold discouragements and hardships.”44 The Home Journal conducted an unofficial phrenological exam on Morse and concluded that he was “forcible, persevering, almost headstrong, self-relying, independent, aspiring, good-hearted, and eminently social, though sufficiently selfish to look well to his own interests.”45 To be sure, he might have been all of those things. Yet Morse thought the answer lay elsewhere.

Grit is a portable skill that moves across seemingly varied interests. Grit can be expressed in your chosen pursuit and appear in multiple domains over time. It can be expressed through the pursuit of painting, and then through the invention of the telegraph. “It is possible to switch course, and still be gritty underneath it all,” Duckworth said.46

Morse documented his process in his letters home through his many decades as an itinerant painter and art student in Europe, and eventually as a professor at New York University. He started studying how others responded to defeat. When he found out that getting into the Royal Academy of Arts in London had recently become “a much harder task” given the new requirement to know anatomy, he wrote to his parents that he felt “rather encouraged from this circumstance, since the harder it is to gain admittance, the greater honor it will be should I enter.”47 When he studied with acclaimed painter Washington Allston in London, he wrote to his family: “It is a mortifying thing . . . when I have been painting all day very hard and begin to be pleased with what I have done, and on showing it to Mr. Allston, with the expectation of praise, and not only of praise but a score of ‘excellents,’ ‘well dones,’ and ‘admirables,’ I say it is mortifying to hear him after a long silence say, “very bad, Sir, that is not flesh, it is ‘mud,’ Sir, it is painted with ‘brick dust and clay.’ ”48 The comments at first made Morse want to “dash” his “palette knife through” his work, but later made him “see that Mr. Allston is not a flatterer but a friend, and that really to improve I must see my faults.”49

As if understanding the color theory all painters know: to create shadow, to give an object depth and volume, you blend its color with one least like it (yellow blends with purple to create a shadow, orange with blue, red with green), and so Morse would study how his icons thrived through adversity. He had studied with legendary president of the Royal Academy and painter Benjamin West, and wanted to know how West had been able to withstand “so much abuse” and “virulence” with a “nobleness of spirit,” remaining “heedless of the sneers, the ridicule, or the detraction of his enemies.”50 He began to look to past artists such as Giotto and Ghirlandaio, whose works some considered “rude, and stiff, and dry,” for their concordant strengths in their quality of expression.51 For decades, Morse’s letters show that he extended this perspective into other fields. On his way to Florence and Rome, he stopped at the island of Elba and lingered in the room that the defeated emperor Napoleon had occupied, and laid on the bed as he “endeavored to conceive for the moment how he, who had in that very situation seen the same objects when he woke, then viewed the reverses of life, to which he had apparently hitherto believed himself superior.”52

Around the same time of his reflections on Jackson’s and Pope Gregory’s responses to defeats, Morse felt his painting began to improve. He started teaching a few students, and settled into a studio on Broadway in New York. “My storms are partly over,” he said, as if previsioning his life.53 Soon after, he would file the patent for the model for the electromagnetic telegraph.

Despite all of the false alarms and setbacks with the telegraph, Morse’s perspective remained. He could respond to his friend that his telegraph “trials” were the things that “accompany the most valuable enterprises,” and, also, that “they are often compensated by important experience, the lessons of which will be profitable for the future.”54

His tenacity is apparent in his attempt to send a message in 1842 through the cable of his recently invented telegraph device from Manhattan to Governors Island, submerged under water over the mile distance. The Herald advertised the event as a chance to witness the device “destined to work a complete revolution in the mode of transmitting intelligence throughout the civilized world.” A few letters went through successfully, then the transmission came to an abrupt end. What looked like failure was, in fact, an accident; a ship crossing the river had entangled the cable in its anchor. The crowd scattered. Morse could barely sleep after what looked like yet another “mortifying” failure. He spent that night considering how the failed trial had mapped his solution. What would happen if he eliminated the wire altogether? Electricity could pass through water itself.55 It led to the breakthrough that let the telegraph cross oceans, one that would take decades to complete.

“I have been told several times since my return that I was born one hundred years too soon for the arts in our country,” Morse once wrote to his friend, Fenimore Cooper. If he was to be a “Pioneer,” he said, he was “fitted for it.”56

Grit gives the impression that it is a straight line, as if we just drill down in ways that may feel uncomfortable, and then improve. “Gritty people have a pattern of staying with one path,” Duckworth has said. “Grit is choosing to show up again and again.”57

Yet, she clarified: “Whatever you’re doing, you have to figure out when to give out effort and when to withdraw it. The really high-functioning people are able to do both; somehow have an eye [for] asking whether they are in the game too long. They have to be willing to commit to higher-level goals by shifting lower-level tactics. The higher level it is, the more you should be tenacious. The lower level it is, the more concrete or particular it is, the more you should be willing to give it up. I think it’s a good rule of thumb.”

I asked her for her thoughts on how we escape the dark side of grit. “I’m not sure we know exactly,” she told me. What makes someone pull back and change course when they’re focused is a hard thing to measure, but, she revealed, “It’s actually on our list to study in the next few years.”

Yet it may be more art than science. It seems to be the riddle of Morse—that true grit is not made up of just grit at all.

Reverberating under the surface of some of these grit pioneers and policymakers—Duckworth, Mischel, Duncan, and Dominic Randolph—seemed to be an interest in how the processes at work in art and design can help cultivate this nimble form of grit, and how central they are for the work and play of innovation. I heard it first from Randolph, the headmaster of Riverdale, which has implemented Duckworth’s ideas about fostering grit into its pedagogy. We barely ate our breakfast one day in June as he interlaced comments about making, spatial and visual thinking, and the pedagogy of art and design that can aid in cultivating this important trait. Most schools are structured around “mono-modal work,” Randolph said, drilling down on one thing without seeing its interrelated connections to other ideas. To teach students about grit, he realized that he would have to have them understand that there is no linear path.

In most public schools in America, the main way to do that is through the arts, and in the United States, the arts have been virtually eliminated since the 1970s. Since 1990, creativity scores have declined in general, but creativity scores for children from kindergarten to the sixth grade, as measured by Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking between 1968 and 2008, have dropped for the first time since its testing began. During the same period, IQ scores have increased each decade.58

As the arts are eliminated, so is the avenue to one of their irreplaceable gifts: the agency to withstand ambiguity long enough to discern whether to pursue a problem or to quit and reassess—when to see, as Morse did, that the painting could also be part of a telegraph. Agency comes from the convergent and divergent thinking that the creative process requires. With the recent decline in our investment in the arts and education, we are smarter, yet less equipped to find novel approaches to problems (as Duncan, too, has noted). If we are low in grit, as well, we are less able to stay with these problems long enough to resolve them.

Randolph had Riverdale begin working with Imagination Playground, a massive block set in weather-resistant blue material with no instructions, developed by architect and designer David Rockwell of the Rockwell Group. It lets “kids build things, and inherent in that process is that they’re going to build things that don’t quite work out,” Randolph says. A third-grade group he observed couldn’t start playing at first. They were stymied with no instructions, no set path. It was “free play with a purpose.”59 It neutralized the negative connotations of setbacks in a developmentally appropriate way.

“The idea of building grit and building self-control is that you get that through failure, and in most highly academic environments in the United States, no one fails anything,” Randolph says.60 Instead, we have a culture where everyone, particularly those in little league athletic competitions, wins some form of a trophy, regardless of how they perform. This form of play, of building, of creating made “having a setback okay.”

What inspired Randolph was an experience he had after college when he wanted to pursue a specific interest—studying copper-plate etching. He traveled to Florence, Italy, and sought out a press that used to cater to Robert Motherwell and Pablo Picasso. There was little instruction in this largely studio-based environment, until one teacher came in and gave him Allston-style feedback. Randolph didn’t know Italian, but said, “I did know what it meant to have my work thrown on the floor. . . . Wood is a very good teacher.”

As Randolph spoke, I realized he was echoing Morse’s comments after his painting critique sessions in Europe. Randolph described the critique as “the strongest experience I’ve ever had in my life.”

When Morse transformed the stretcher bars of the canvas into the telegraph, he was still, in essence, making things. He was no scientist. He was no Lord Kelvin. He was still pioneering through intelligent facture. The telegraph was not his first invention. Years earlier, he had come up with a machine to reproduce marble sculpture that he couldn’t patent, along with a leather piston.61 He had studied developments in electricity with Professor James Freeman Dana of Columbia College. He was also one of the first in America to experiment with the early form of photography, the daguerreotype, having learned the technique in Paris from Louis Daguerre. Morse was still innovating through making, playing, using what art historian Henri Focillon called “the mind in the hand.”62

As Morse invented the telegraph, he had spent over twenty years in a field where grit and reframing are prerequisites. In the arts, to persist regardless of public opinion is a matter of survival. This skill, nearly as important as talent, means focusing as much on process as outcome.

The “crit.” This is the creative environment where Morse’s letters reveal that he experienced this limber form of grit. Short for critique, the crit process remains the core activity in arts programs around the country such as the Yale School of Art, centuries after Morse walked the school’s campus as an undergraduate. In Yale’s Photography Department, the crit process happens in “the pool,” and in the Painting and Printmaking Department, they take place in “the pit”—both rectangular rooms below the main floor of their respective buildings that heighten a sense of inspection. A student often sits on a stool or chair for forty-five minutes as the faculty and, at times, other MFA students discuss his or her work displayed on the surrounding walls. To hear Yale MFA graduate and painter Lisa Yuskavage reflect on it, a crit can feel like “the general nightmare of standing nude in public,” but with the added dimension of “something else you fear, like standing nude on a scale.”63 Perhaps it feels this way because constructive honesty has long remained its ethic.

“Art comes out of failure,” said legendary conceptual artist John Baldessari, who set up the “Post Studio” crit sessions at California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) in 1970, the school’s inaugural year. He famously incinerated an entire body of acclaimed work he had made from 1953 to 1966 that didn’t meet his own standards—his Cremation Project (1970). “You have to try things out. You can’t sit around, terrified of being incorrect, saying, ‘I won’t do anything until I do a masterpiece.’ ”64

The goal of the crit is to help the student close the gap between their intentions and the work’s effect. It can mean withstanding, as Morse said, a brutal, “mortifying” comment. To hear conceptual artist Mel Bochner, a highly respected former Yale faculty member, say to a student in this audience-filled group crit, “Go back to the library and start with A,” as he once did to an MFA student with a wispy grasp of art history, is not uncommon.65 Of course, external and internal criticism can become too much and can crush the creative spirit, launching attacks that no defense mechanism can withstand, yet the grit that polished Morse’s own practice in Europe with Allston is still the essence of this crit.

Crits are part of how artists learn the paradox of creative balance.66 Part of it means learning the wisdom that painter Elizabeth Murray knew, that “to be right doesn’t mean that everyone else has to be wrong.” It is a benevolent approach to art-making paths that photographer Gregory Crewdson understands as head of the Photography Department at the Yale School of Art, encouraging artists to “find that 1 percent that really helps you” and just “forget 99 percent of what [you] hear.”67 The constant reframing these crits require helps artists sort out the riddle of the blank review, figuring out what feedback to ignore and what 1 percent is crucial to absorb.

The crit embodies the wisdom of the circle. It is at the heart of the myth of the trickster deity Eshu-Elegba, the West African Yoruba legend I learned from the legendary art historian Robert Farris Thompson.68 Disguised as a man, Eshu-Elegba strolled through a town in a cap topped with a crimson parrot feather, half painted white and the other half red, bisected by a line from the middle of his forehead to the top of his spine. Some in the town thought that they saw him walk by in a red cap. Others thought it was white. One person who had swept through the entire town knew that the cap was both colors. Chinua Achebe described the lesson of the myth in reference to an Igbo festival masquerade: “If you want to see it well, you must not stand in one place . . . If you’re rooted to a spot, you miss a lot of the grace.”69 This is the meaning at the heart of the legend about the crossroads, and the crit—you can’t know a subject until you’ve walked its circumference, seen it from as many perspectives as possible, then taken its full measure.

We reframe when we consider not only what subject the artist has made his or her own, but what self-defined problem their body of work is trying to solve, like Cézanne’s aim of realizing nature in paint, or Morse trying to make the genre of history painting extend to a quotidian scene in the Louvre. “Every important work of art can be regarded both as a historical event and as a hard-won solution to some problem,” art historian George Kubler said about the entire arc of artistic production in The Shape of Time, his seminal text describing what he sees as the generative force behind artistic development across the ages.70 Some artists, he argued, were dealing with foundational questions, what he calls “prime objects”—questions that can’t be divided or nuanced further and thus lead to an unending chain of potential answers, the query is so essential and irreducible. “The important clue is that any solution points to the existence of some problem,” he said. “As the solutions accumulate,” he continued, “the problem alters.”71

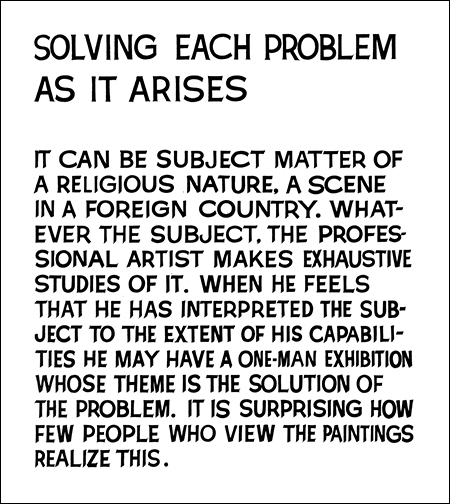

Many artists speak about their work in this unexpected way. Among them is Frank Gehry, who considers architecture to be about “bringing an informed aesethetic point of view to a visual problem.”72 Miró, who wrote to J. F. Ràfols Montroig about his excitement in “discovering new problems!!,” felt that would carry him from “deadly momentarily interesting work to really good painting.” Baldessari created a piece about how addressing problems is a tenet of art-making itself73:

John Baldessari, Solving Each Problem As It Arises, 1966–68. Acrylic on canvas 172.1 x 143.5 cm (67 3/4 x 56 1/2 in.). Yale University Art Gallery. Janet and Simeon Braguin Fund, 2001.3.1.

“Often people miss insights because they are not looking at it as a problem. It’s important to ask ‘Why,’ not ‘what,’ said James Watson. A shift between focused sight and peripheral vision comes when you consider your work in progress as an issue for which you aim to find a solution. It’s why dancer and choreographer Twyla Tharp advocates picking a fight as a way to find out what issue you’re trying to deal with, what you’re willing to fight to express.74 For at the heart of every innovator is a rebel, someone dissatisfied with the status quo. Yet the rebel’s affirmative cause often remains undefined. Determining what you’re fighting for helps to discern it.

“It’s important to be able to move beyond someone or something,” Watson told me. Framing ideas as a problem puts us on the quest to pursue what seems incomplete.

“Fields die just because no one thinks they can outdo what has been done.”75

Reframing our projects as a problem to solve happens through creating a series of amended pictures. This inner pictorial process helps us adjust our goals. It occurs not just with artistic practice, but also through visual thinking.

Reframing can turn an artist’s studio into a laboratory, combining things never before considered. Perhaps not all are as obvious as Morse’s. His students recalled seeing galvanic batteries, wires, and wooden materials strewn about his Washington Square space and the “sketch upon the canvas untouched.”76 One student, Daniel Huntington, remembers Morse’s studio with details about his teacher mixing colors with milk, at times with beer, as if having observed an experiment.77 On September 2, 1837, at NYU, Morse debuted the telegraph device, a tracing of dots and dashes. He had learned to sketch another way.

Many have argued that there is a need to bring the arts and sciences together. A clarion call to connect art and science came after C. P. Snow’s 1959 lecture “The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution” made the claim that we needed to better perceive the connections between science and literary intellectuals in Western culture.78 Sociobiologist Edward O. Wilson later said that there should be a “consilience” between art and science.79 Former NASA astronaut Mae Jemison took selected images with her on her first trip to space, including a poster of dancer and former artistic director of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater Judith Jamison performing the dance Cry, and a Bundu statue from Sierra Leone, because, as she said, “the creativity that allowed us . . . to conceive and build and launch the space shuttle, springs from the same source as the imagination and analysis it took to carve a Bundu statue, or the ingenuity it took to design, choreograph, and stage ‘Cry.’ . . . That’s what we have to reconcile in our minds, how these things fit together.”80 As a jazz musician once told me, musicians are mathematicians as well as artists.

Morse’s story suggests that the argument started not because of the need to bring art and science together, but because they were once not so far apart.81 When Frank Jewett Mather Jr. of The Nation stated that Morse “was an inventor superimposed upon an artist,” it was factually true.82 Equally true is that Morse could become an inventor because he was an artist all the while.

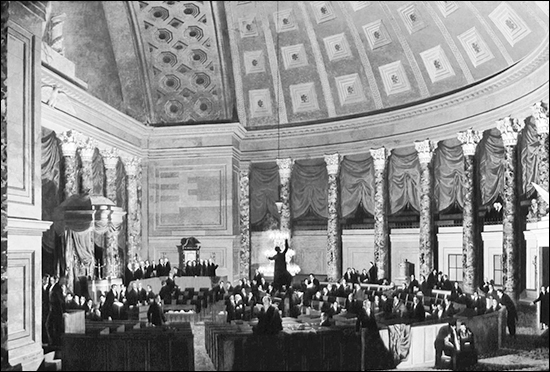

In one of the final paintings that laid him flat, the painting that failed to secure his last attempt at a commission, one he had worked fifteen years to achieve, Morse may have left a clue about his shift from art to invention, and the fact that the skills required for both are the same. He painted The House of Representatives (1822–23) as evidence of his suitability for a commission from Congress to complete a suite of paintings that still adorn the U.S. Capitol building. The painting has an odd compositional focus. In the center is a man screwing in an oil chandelier, preoccupied with currents.

Morse was “rejected beyond hope of appeal” by the congressional commission led by John Quincy Adams. When he toured the picture for seven weeks—displayed in a coffee house in Salem, Massachusetts, and at exhibitions in New York, Boston, Middleton, and Hartford, Connecticut—it lost twenty dollars in the first two weeks. Compounded by a litany of embarrassing, near-soul-stealing artistic failures, he took to his bed for weeks, “more seriously depressed than ever.” This final rejection forced him to shift his energies to his telegraph invention.83 By 1844 Morse went to the Capitol focused on a current that would occupy the work of Congress—obtaining a patent for the telegraph.

Samuel F. B. Morse, The House of Representatives, 1822–23. Oil on canvas. 86 7/8 × 130 5/8 in. Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D. C. Museum purchase, Gallery Fund.

In 1932, during the centennial celebration of Morse’s telegraph innovation, his work as a painter came to much of the public as a shock. A student of Morse’s, Samuel Isham, seemed to sense that his teacher’s invention might become disconnected from its artistic foundation. Yet Isham hoped we would all remember how “the qualities of mind which led to” his painting professor’s “world-wide fame” were, in fact, “developed in the progress of his art studies.”84 Morse, too, felt that the had always kept “an Artist’s heart.”85

If we fail to cultivate grit, it is also because we often grant little importance to the practice of making and the process that it can teach us throughout our lives.

Inventions come from those who can view a familiar set of variables from a radical perspective and see new possibilities. Creative practice is one of the most effective teachers of the spry movement of this perspective shift. It offers agency, required for supple, nimble endurance that helps us to sense when the bridge is about to collapse. It lets us shift our frame, like a painter who stared at a set of canvas stretcher bars for years and one day saw its potential to be an original communication device. And then persisted for decades to realize its full application for the world.

When I arrived at Locust Grove, Morse’s Italianate villa in Poughkeepsie, I strained to see it. His main request of the architect’s redesign was that there be no direct line of sight from his garden to his house. Seeing it fully should require a series of moves and turns. He only wanted the approach to be of bits of the house “peeping through the verdure.”86 Landscaping traditions at the time made that style au courant. It was a fitting conceptual approach to a house for a man who once wanted to be as pioneering as Rembrandt, but was then an American hero entering the same league as Benjamin Franklin, so well known that he simply wanted, as he wrote to a friend, “Obscurity.”87 This jagged path also mimed the agile darting that led to his feats. It was an example of what this deft form of grit can look like in action.

Our stories constitute their own human science—felt-facts long before studies could confirm them, our earliest form of psychology.88 Perhaps this is why there is a myth about inventors and artists of all kinds, such as there was about Morse when he lived. He never entirely gave up on his first ambition. “I sometimes indulge a vague dream that I may paint again,” he confessed to Fenimore Cooper.89 The man who once spent each working day for months in the Louvre would later visit countries and never venture into a single museum. Yet he would later call his telegraph invention part of “the Arts” of this country.90 It is, too, the art of how we create out of seeming ruin.

After World War II, the telephone took the path laid down by the telegraph; “sounders” and clicking devices would replace paper tape recordings; fiber optic cables replaced the insulated copper conducting wires along oceans—yet the telegraph remains a foundational bridge that connects continents, built around the globe.91

Decoding how to cultivate grit would be “akin to discovering the semiconductor,” Duckworth said.92 She is currently collaborating with Walter Mischel of Columbia University, the pioneer of self-control studies, to see how people develop this pliant trait.

What are the inner resources required for grit, and are they truly all within, I wondered, as I thought about the mentorship Duckworth found in her husband, Randolph found in his Italian instructor, Morse found in Allston, and many artists find in the crits they receive from others.

It seemed like the right time to describe Morse’s nimble path. She smiled and within a second recalled Mischel’s answer to a question posed to him by New York Times reporter David Brooks during a public interview at the Association for Psychological Science. What might Mischel choose to become if he had to do it all over again? He paused, reflected on it, and said, “I might become a painter.”93