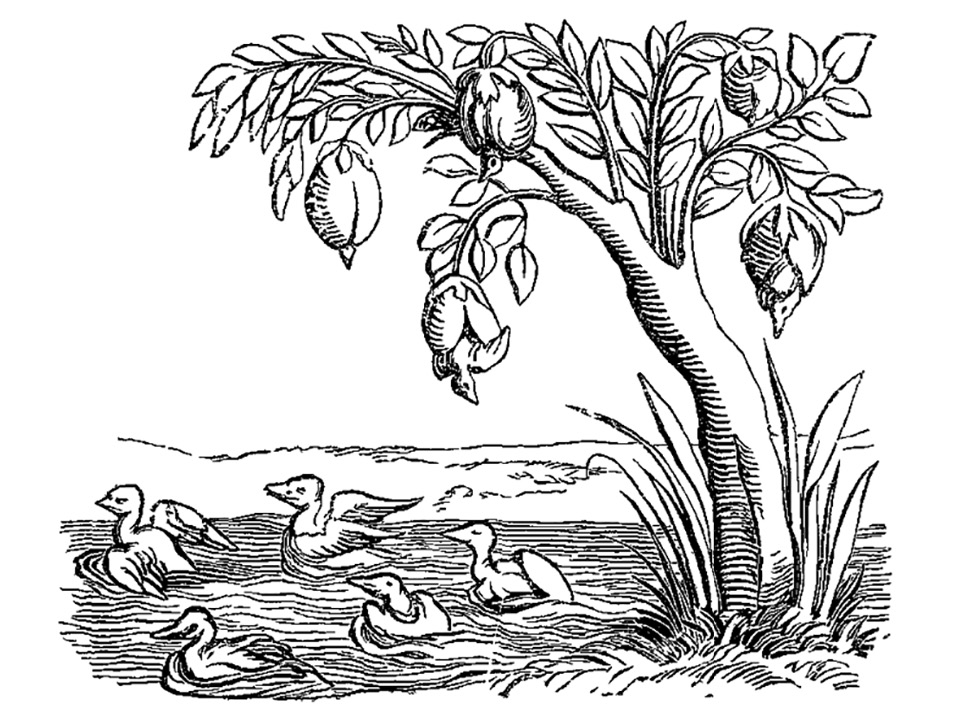

The bernicla, or barnacle tree, with fruit transforming into geese

Four

Vegetable Lambs and Barnacle Trees

In late fall of 1729, two friends divided up the world between themselves.

One of them was Carl Linnaeus, retrieved from the edge of destitution by his chance encounter with Professor Celsius. In addition to providing room and board, his new mentor had arranged to upgrade Linnaeus’s scholarship, securing his studies for another year. No longer consumed by maintaining a precarious existence, Linnaeus was at last able to enjoy the non-academic aspects of student life: lingering in cafés, engaging in leisurely extracurricular discussions, and forging friendships.

Peter Artedi, two years older and from the northern Swedish province of Ångermanland, had a background remarkably similar to that of Linnaeus. He too was a pastor’s son, with a Latin surname coined by his father. He’d also been raised to inherit the family pulpit, developed a fixation on natural history, and been shunted off to medical school instead. Linnaeus had noticed him months earlier in the university library, and silently registered that they seemed interested in the same books, but had not felt confident to approach Artedi until recently. Once he struck up a conversation, the floodgates opened. “We immediately started talking about stones, plants and animals,” Linnaeus recalled. “I wanted his friendship; and not only did he give it to me, but he also promised me his help whenever I needed it.”

Physically and temperamentally, they were markedly different. Linnaeus described Artedi as “tall, slow and serious,” at the same time describing himself as “small, giddy, hasty and quick.” Artedi was inclined to sleep all day and work at night, while Linnaeus was an early riser who kept regular hours. But they were fast friends, and determined not to become rivals. As a measure against future conflicts in their careers, they divided up the living world between themselves. Linnaeus would study insects and birds, and Artedi would take fishes (then a term for all aquatic creatures), reptiles, and amphibians. Trichozoologia (“hairy animals”) would be catalogued collaboratively: Both could study as many as they chose, so long as each informed the other first. Knowing that Linnaeus’s chief interest lay in plants, Artedi deferentially chose only a few of them, chiefly carrots, parsley, and celery. They also agreed to safeguard each other’s legacy: In the case of one’s death, both vowed, the other would take possession of the deceased’s research papers and carry on in his stead.

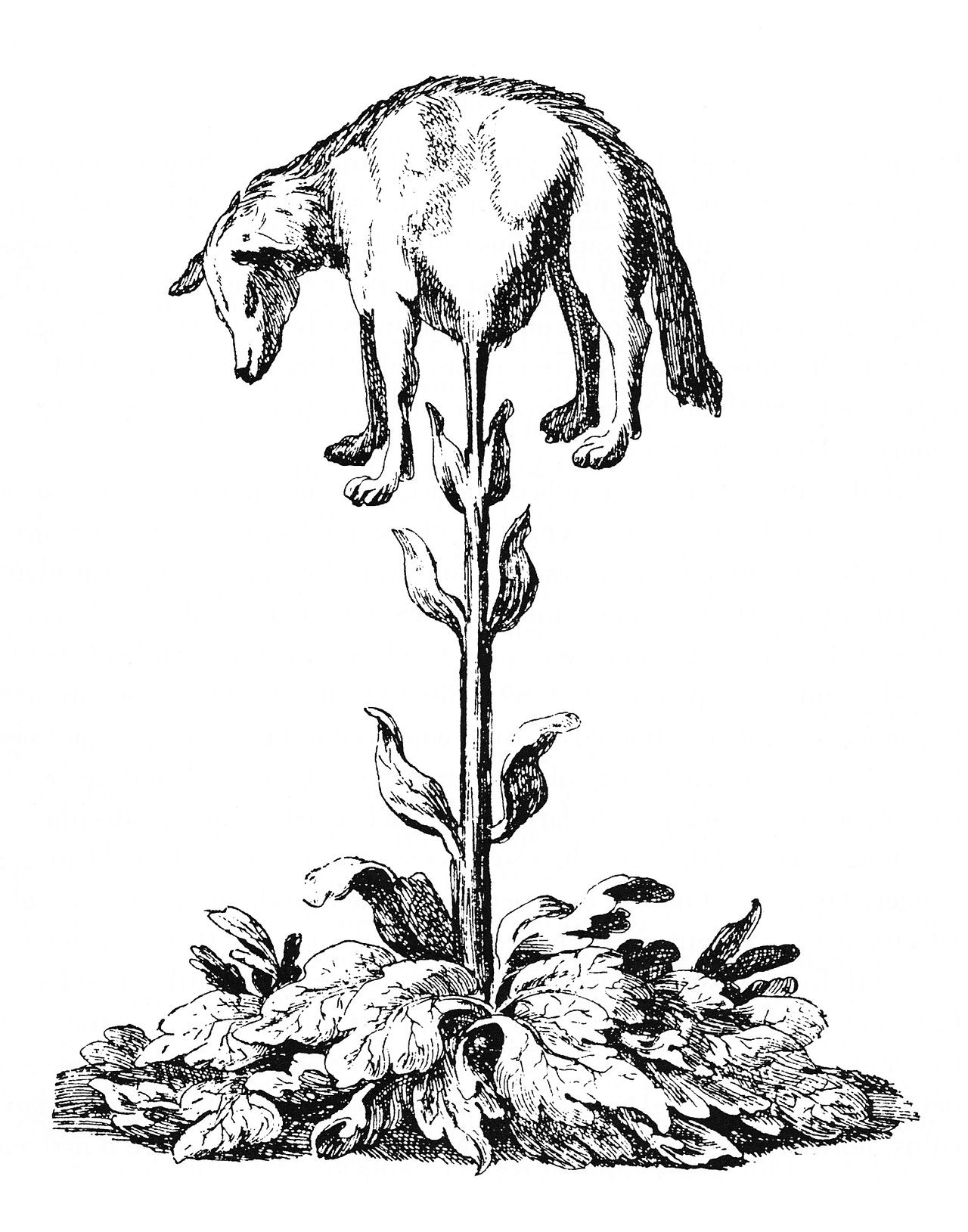

Yet as their amicable division of all life grew more detailed, Artedi and Linnaeus were confronted by the fact that no matter how neatly they drew their boundaries, some species refused to respect them. There was, for instance, the boramez, or vegetable lamb of Tartary. Reportedly native to parts of Asia bounded by the Caspian Sea, the boramez was an animal like an ordinary lamb, except it was also a plant. It emerged from the earth suspended on a stalk that served as a sort of rigid umbilical cord; the lamb would die if it was cut. It did not live long, as it could only graze on grass in its stem’s perimeter. Its meat tasted like mutton, but its blood tasted like honey.

The boramez

Then there was the bernicla, the barnacle goose tree. Supposedly native to a small island off the coast of Lancashire, the tree gave forth fruit in the form of barnacles, which dropped into the water and, after a few submerged months, emerged as geese. This was an especially tricky question for Linnaeus’s and Artedi’s respective specialties, as it was simultaneously a plant, a fish, and a bird. According to John Gerard, an English naturalist, these mussel-shaped shells would grow until they split open, revealing

the legs of the Birde hanging out, til at length it is all come foorth. The bird would hang by its bill until fully mature, then would drop into the sea. Where it gathereth feathers, and groweth to a foule, bigger than a Mallard, and lesser than a Goose.

Were such fantastical species taken seriously in 1729? Barring a few skeptics, very much so. The vegetable lamb had its own entry in Ephraim Chamber’s Cyclopaedia, or a Universal Dictionary of Arts and Science, published just the year previously. In Gerard’s Herball, published in 1636 but used as a teaching text well into the nineteenth century, the barnacle tree is authoritatively catalogued, side by side with a description of a potato. Pope Innocent III had explicitly prohibited the eating of barnacle geese during Lent, deciding that despite their unusual reproduction, they lived and fed like conventional geese and so were of the same nature as other birds. In Jewish dietary law, Rabbeinu Tam had determined that they were kosher, and should be slaughtered following the normal prescriptions for birds.

To modern eyes, such creatures are patently impossible. The vegetable lamb likely arose from a misreading of Herodotus, who wrote of a plant whose “fruit whereof is a wool exceeding in beauty and goodness that of sheep.” He was describing cotton. Until closed by Innocent III and Rabbeinu Tam, the barnacle tree was probably a fictional loophole for those who wished to eat fowl but pretend it was fish. To understand why even experienced naturalists documented their existence without blinking, it’s helpful to understand the near-universal acceptance of a master plan for organizing all life, a pattern commonly acknowledged as existing in nature.

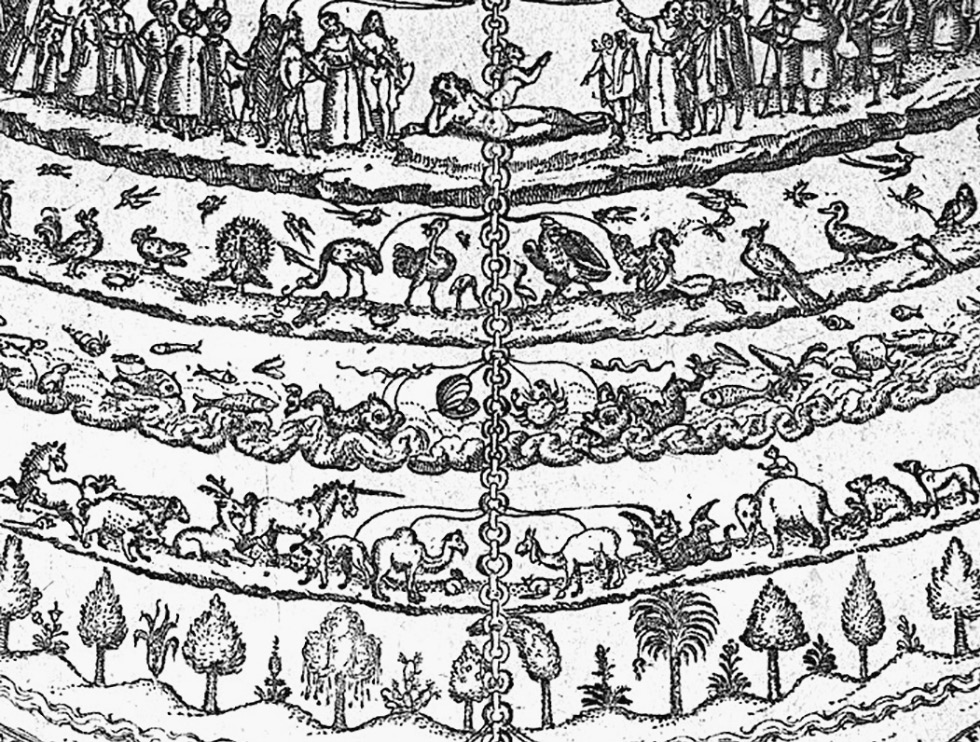

It was a straight, ascending line.

First popularized by Aristotle in his History of Animals as the concept of scala naturae, or Ladder of Life, the schema was simple: a single line of increasing sophistication—commonly known as “perfection”—rising from simple plant life at the bottom step to humanity at the topmost. Further elaboration over the centuries transformed the rungs of the ladder into the links of a chain, refining the metaphor into a Great Chain of Being. At the bottom, the chain descended to mineral life. At the top it stretched up past humanity, to angels and finally to God Himself. Creatures like the bernicla and boramez struck no one as a violation of categories, as they constituted their own categories, their own links on the chain. If anything, intermediary organisms like vegetable lambs and geese-fruiting trees seemed necessary linkages from one level of perfection to another.

The Great Chain of Being was more than a metaphor. It was an instrument of temporal power. The particulars varied from version to version, but many depictions of the Great Chain awarded kings and nobility their own links, directly above ordinary people, thereby giving sanction to a ruling class as an integral aspect of the natural order. This attitude would be codified into the eighteenth-century hymn “All Things Bright and Beautiful”:

The rich man in his castle

The poor man at his gate

God made them high or lowly,

And ordered their estate.

The Great Chain reinforced a monarchical perspective in lesser realms as well. The eagle was elevated to the status of the “king” of birds. Typically the elephant or the lion was heralded as the king of beasts, and the whale the king of fishes. The oak tree was the king of plants. Extending beyond living things, the Great Chain declared gold the king of metals, diamonds the king of gems, and marble the king of stones. By the late Renaissance, the Great Chain of Being was displaying even more precise calibrations. Wild animals held higher place than domesticated ones, since their untamed nature was evidence of larger souls. Worm-eating birds were higher than seed-eating ones. Celestial beings were introduced toward the top of the hierarchy, with seraphim declared the highest order of angels—since a seraphim was king, or “primate,” of the angels.

The Great Chain of Being (detail), from Rhetorica Christiana, 1579

The schema grew in both complexity and acceptance, to the extent that by 1667 the scholarly British Royal Society was defining its mission in direct relation to the chain:

This is the highest pitch of humane reason: to follow all the links of this chain, till all their secrets are opened to our minds; and their works advance’d and imitated by our hands. This is truly to command the world; to rank all the varieties and degrees of things so orderly upon one another…we make a second advantage of this rising grouynd, thereby to look the nearer into heaven.

Yet for all the praise it had garnered over the centuries, the Great Chain raised a host of questions. If the lion was king of the animals, were other cats higher up on the chain than dogs? Were nutritious turnips more “perfected” than ornamental rosebushes? Such questions were debated by students like Linnaeus and Artedi, but there were no clear answers.

The respectability conferred by Celsius’s patronage had opened up another vista of opportunity for Linnaeus, namely a lucrative trade in tutoring his fellow medical students. They were turning to him in increasing numbers, drawn by his real-world experience—unlike most of them, he’d spent a year assisting a practicing physician. His time with Dr. Rothman in the village of Växjö would, ultimately, be the only meaningful medical education Linnaeus would ever receive, and at the moment it made him a valuable if somewhat circumspect resource.

Rothman had begun Linnaeus’s medical apprenticeship by instructing him in two subjects. The first was physiology, the mechanics of how the body works. During the course of his village rounds, he’d prompted Linnaeus to study the articulation of a patient’s limbs, to see and feel how muscle and bone connect and coordinate, and to notice how illness or injury impeded that motion. A gash or a broken bone was a rare opportunity to witness flashes of the interior body itself, glimpsed between pulsings and blood. That was why Linnaeus had paid most of his scholarship money to witness the dissection of the executed woman in Stockholm: to confirm his mental picture of the world beneath the skin.

The second subject was materia medica, the identification and preparation of substances used in medicine. Aside from a few items such as tincture of opium, drugs in the modern sense of the term did not exist. In their place was an arsenal of salves, poultices, elixirs, and other concoctions collectively known as physicks, a term that gave rise to calling the doctors who applied them “physicians.” A precursor of pharmacology, materia medica was essentially a stock of recipes for physicks, accompanied with instructions on how to obtain the necessary therapeutic ingredients. Some treatments were readily available: Patients suffering from lethargy, diarrhea, or postpartum pain were frequently prescribed generous amounts of wine, and asthmatics were treated with red sugar candy. Some physicks involved animals: The ague, for instance, was treated by wrapping the patient in the skin of a freshly killed lamb. Others were mineral in nature: Paralysis, bad breath, and melancholy were treated with Aurum potabile, a drinkable suspension of flecks of gold. But most physicks drew their primary ingredients from plants. Carl learned to identify a plant and harvest its medicinal components, quickly and with confidence.

Unusually for his era, Rothman had cautioned Linnaeus against use of the Doctrine of Signatures, a philosophy of materia medica commonly accepted at the time. Rooted in prehistory but refined in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, this was the belief that each plant had been designed by God to serve a specific human purpose, and that clues to that purpose were conveniently incorporated into the plant’s appearance. Hence a blood-red leaf was the sign that a plant helped strengthen the blood. The walnut, because it resembled a human brain, treated mental illness. Strong-smelling plants, because they excited the nose, would excite a patient’s nerves when ingested. The notion was patently flawed and even dangerous: Birthwort, a plant commonly administered to pregnant women because its flowers resembled birth canals, is now linked to kidney disease and cancer. But this idea would hold a place in mainstream medicine for generations to come.

While Linnaeus’s rejection of signatures reduced the amount of minutiae to memorize, even his version of materia medica could not be gleaned solely from books. Most texts on medicinal plants, if illustrated at all, had only moderately detailed woodcuts or engravings of the plants themselves, insufficiently detailed for the student to accurately locate them in the field. Rothman had given Linnaeus access to a copy of the standard work on the subject, Theophrastus’s Historia Plantarum, but it was more confusing than useful. In addition to being over two thousand years old (Theophrastus had been a pupil of Aristotle), the text only described about five hundred kinds of plants, few of which were found in northern Europe. Linnaeus attempted to reconcile Theophrastus with the plants of southern Sweden, but found that “there were many which had not at the time been examined with sufficient botanical accuracy, and which, not being reducible to the rules of that system, involved our young botanist [himself] in great perplexity.”

Even well-known plants were difficult to recognize in the pages of Theophrastus, who could only describe by painting word pictures, using comparisons now obscured by two millennia. For instance, his description of the sacred lotus (Nolumbo nucifera) compares the stalk to the thickness of a man’s finger, the flower bud to a wasp’s nest, and the blades of its leaves to a Thessalian hat. How large was a Thessalian hat? The question was as mysterious to Linnaeus as it was to Rothman, who admonished his apprentice not to put too much stock in Theophrastus, or for that matter formal classical identification in general. “To know a flighty Latin word or the name of a plant was nothing,” he’d informed his pupil, urging him to rely on his own senses and field experience.

Yet ancient names were an essential aspect of European medicine. They transcended regional differences, as illustrated by Linnaeus’s namesake tree. In Sweden it was called lind. In Germany it was linden, in Romania it was tei, and in England it was either basswood or lime (the latter being a further confusion, as it bore no relation to the citrus tree of the same name). But a Swede, a German, a Romanian, and an Englishman could all discuss the same tree by referring to it as tilia, the term used in Latin translations of Historia Plantarum. The use of Latin names was more than a tribute to antiquity. It was a tool for contemporary clarity.

Such practice required going beyond the ancients. It was necessary to coin Latin names for plants that Theophrastus and others of his era never mentioned. The challenge of this was embodied by a book Rothman had made available to Linnaeus: Elements of Botany, or A Method for Recognizing Plants, by the French botanist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, laboriously translated into academic Latin as Institutiones Rei Herbariae. The translation had taken over five years to produce, as it required tracking down or inventing Latin names for nearly seven thousand plants.

The materia medica Linnaeus had learned—and was now trying to teach his fellow students—was subtle and contextual, informed by the observation that many plants’ appearances and even medical properties change throughout the year. In ripened form the flåderbår, or elderberry, is a staple of Swedish cuisine; in immature form it looks less like a berry than a kind of pea, and is poisonous. Different parts of a plant yielded different treatments as well, as in the case of the linden, Linnaeus’s own namesake tree. Leaving aside the dubious Doctrine of Signatures (which held that its heart-shaped leaves were good for irregular heartbeats), practical experience showed that a linden tea—brewed from blossoms, not leaves—could combat anxiety. However, the same tea might exacerbate the symptoms of someone feeling dizzy or light-headed, in which case a better treatment might be a decoction of bark from the same tree. Linnaeus could teach these nuances in the abstract, but the efficacy of such medicine still hinged on deriving treatments from the correct plant, not a similar-appearing one. How to be certain? In the absence of extensive time in the field, Tournefort provided an alternative.

Institutiones Rei Herbariae was not strictly part of the medical curriculum, since it encompassed plants with no known medicinal purpose. Yet Linnaeus had been enthralled, not only by the book’s massive scope but also by its attempt to organize the subject into an overarching whole. Tournefort’s system separated trees from herbs, then classified the latter chiefly on the characteristics of their petals. Since some plants had no petals (these were classified as “apetalous”), the schema was not a model of clarity, and even this pared-down approach quickly bogged down in complexity. After dividing plants into 22 distinct petal-shape groupings, Tournefort further subdivided them into 698 genera, broad categories based on other physical resemblances. There Tournefort halted. The book’s subtitle was “a method for recognizing plants,” but sorting nearly seven thousand plants into nearly seven hundred categories only brought the reader partway down the path of recognizing individual species. For field identification, one would either need to tote along a very large book or memorize all 698 genera.

Linnaeus the medical apprentice had memorized them, but Linnaeus the tutor found few of his fellow students interested in putting forth a similar effort. Or, for that matter, much effort at all. Why go to the trouble? Their professors administered no tests, engaged in no classroom discussions, and only evaluated students based on submitted written work. Not overly bound by scruples, Linnaeus let out discreet word: For the proper fee, he’d not only edit their papers but write them himself. This dubious trade kept him busy and well compensated until December, when another writing project loomed, one that he dreaded. It was time to write a poem.

Uppsala students under a professor’s mentorship were traditionally expected to present their patrons with an original poem of praise on New Year’s Day. Linnaeus did not feel remotely up to the task of composing verse, but ghostwriting and the tedium of trying to pound Tournefort through his fellow students’ heads had started him thinking about a streamlined, easier-to-grasp approach to plant identification. In the waning days of 1729, he began work on an alternative gift for Professor Celsius. I am no poet but something, however, of a botanist, he wrote in Swedish, taking care not to blot lines or waste paper. I therefore offer you this fruit from the little crop that God has granted me.