The Jardin du Roi, Paris

Nine

An Abridgment of the World Entire

If Linnaeus took note of the Tuileries Palace, the Louvre, the cathedral of Notre Dame, or any of the other landmarks of Paris when he arrived in June of 1738, it was only while striding purposefully past them on his way toward the semi-rural eastern edge of the city. There, hemmed in by a monastery and the municipal market for horses and pigs, stood a patch of green: the Jardin du Roi, a royal garden in a decidedly unroyal setting. To Linnaeus’s eyes, it was one of the marvels of the world.

The Jardin was a unique institution, in large part because it pretended to be no institution at all. Created in the previous century as a stealth project to subvert the academic status quo, it had survived and even flourished. Yet its very existence remained controversial.

As both law and long-standing tradition dictated, the teaching of medicine in Paris was the sole purview of the University of Paris, colloquially known as the Sorbonne. Since its founding in 1150, the Sorbonne had created and formalized many of the core concepts of higher education: strict qualifications for professors, the system of chancellors and deans, and the awarding of doctorate degrees. But five centuries had ossified several of the Sorbonne’s departments into hyper-conservative, static bodies. Particularly hidebound was the college of medicine, which conducted no research, held no classes other than lectures, and stuck to a dusty curriculum that did not extend past the writings of Galen, the Greek physician born in 129 a.d. By 1626, King Louis XIII had so little confidence in Sorbonne-trained doctors that he appointed as his personal physician one Guy de la Brosse, a man whose primary qualification was that he had studied in the provinces, not Paris.

De la Brosse wished to break the Sorbonne’s ancient monopoly on medical instruction. He found a sympathetic ear in the king’s chief minister Cardinal Richelieu, who ultimately counseled an oblique approach. At Richelieu’s prompting, the king commissioned de la Brosse to plant a garden in the Faubourg Saint-Victor, a sparsely settled area then technically outside the city. The Jardin Royal des Plantes Médicinales, as it was then called, would serve as the monarch’s personal medical chest, a ready source of the ingredients for physicks, poultices, and decoctions. Nearly two thousand botanical varieties took root there over the next five years.

Since the king’s physician would naturally need to compound such treatments at a moment’s notice, the Jardin acquired buildings to house apothecaries and their requisite equipment. The king then commanded that the royal medicine chest be expanded to a stockpile of every drug known to exist. This called for the construction of a warehouse, the addition of a staff to attend it, and an ongoing research program to ensure the collection stayed up to date. As this new concentration of natural knowledge could benefit kingdom as well as king, Louis XIII magnanimously allowed de la Brosse to share the Jardin with other physicians. For that matter, even medical students were welcome.

The Sorbonne howled. This was clearly an attempt to teach medicine, in violation of their sanctioned exclusivity. The king sidestepped their protests, maintaining that the Jardin was not a school but simply a garden: It held no entrance examinations, charged no tuition, and awarded no degrees. Yes, the grounds now employed several learned gentlemen to hold forth on various topics in botany, chemistry, and even anatomy, but they were “demonstrators,” not professors, and what appeared to be lectures were only demonstrations. The stockpile of drugs expanded into a burgeoning collection of “all rare things found in nature,” designated the Cabinet du Roi (natural history collections were commonly referred to as “cabinets,” no matter how vast they might be). As a final proof that the Jardin did not encroach upon the Sorbonne’s monopoly, in 1640 the gates were thrown open to the public. Now anyone who wished could stroll the grounds, wander into demonstrations, and enjoy a convivial exchange of knowledge that was most certainly in no way a formal education.

The Sorbonne continued to lodge numerous complaints with the French parliament. Rumors spread that de la Brosse was an atheist and a libertine, taking advantage of the isolated location to conduct orgies. The Sorbonne faculty grew especially enraged in 1673, when the Jardin’s “demonstrators” were audacious enough to demonstrate the circulation of blood, a principle discovered by Sir William Harvey in England a scant forty-five years earlier. Yet the Jardin Royal des Plantes Médicinales, eventually renamed the Jardin du Roi, endured as a technically non-academic educational institution, as four generations of intendants presided over what remained an egalitarian anomaly.

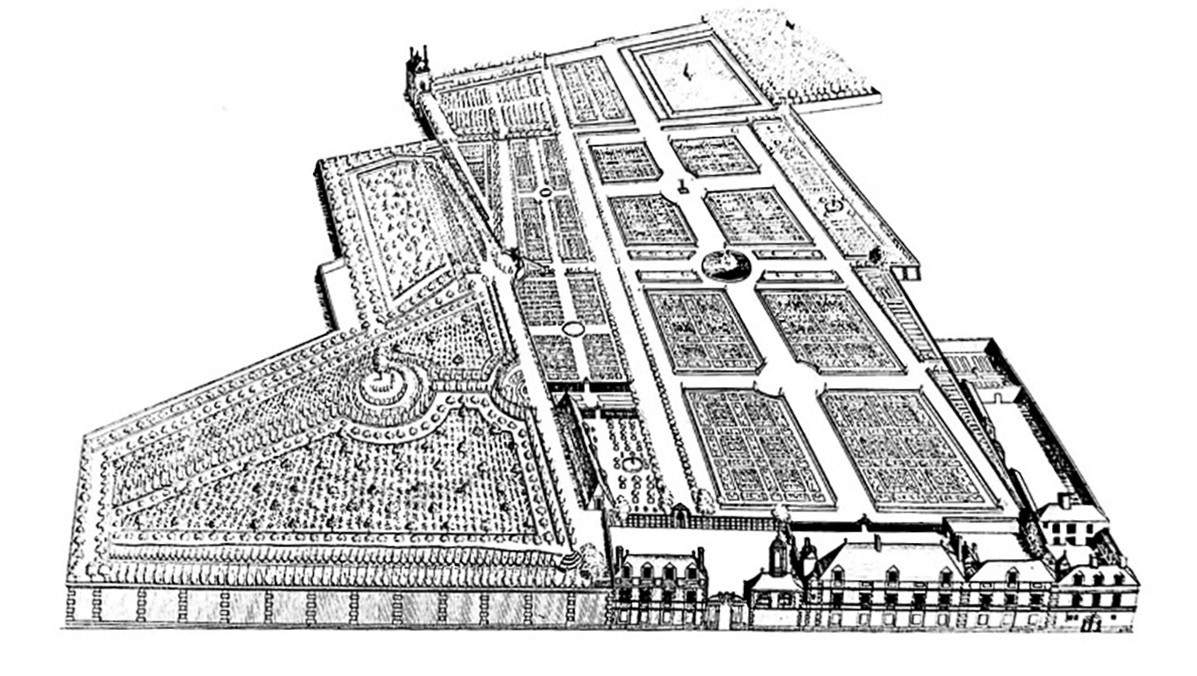

For Linnaeus it was hallowed ground. It was here that Tournefort had created his botanical system with 643 categories and where Valliant had put forth the idea that plants had sexual organs. The gates now opened to a lush campus of nearly twenty acres, with an amphitheater for chemistry demonstrations and (as was customary due to noxious odors) a separate structure for demonstrating anatomy. When it proved impractical to level a small hill in the eastern corner, Guy de la Brosse had incorporated it as a vista, landscaping a winding circular path along its height and planting a single tree at the summit, where it sheltered visitors enjoying views of the Seine and the surrounding countryside. Most of the public were content to enjoy that view, to stroll the geometrically tidy planting beds, and to tour the Cabinet of the King. But others lingered, learned, and marveled. Here, “one has found the means of shortening and flattening the surface of the earth,” the philosopher Denis Diderot wrote of the Jardin. “Here one sees productions from all the countries in the world, and so to speak an abridgment of the world entire.”

Linnaeus was eager to test the premise that anyone could wander into a class in session. When he saw a group gathering around one of the garden’s demonstrators, he quietly joined them. They were listening to thirty-seven-year-old Bernard de Jussieu, a Lyonnaise apothecary’s son who had joined the staff at the age of nineteen.

Bernard de Jussieu

The informal class was a refreshing departure for Linnaeus, who was used to elderly professors droning on from prepared texts. The genial, good-natured Jussieu engaged directly with his audience, asking questions of them and tailoring his explanations accordingly. When Jussieu pointed out a plant and asked if anyone present could identify its origin, a voice confidently rang out in Latin.

“Facies Americana.” The plant is native to the Americas.

“Tu es Diabolis aut Linnaeus,” Jussieu replied. You are either the Devil or Linnaeus.

It was a dramatic meeting, but not a startling one. Linnaeus would later cite the encounter as proof of his fame preceding him, but in truth he’d already paid a social call to the Jussieu household, leaving behind a memorably immodest letter of introduction (“Behold Charles Linnaeus, the prince of botany, if ever one existed”). Jussieu was familiar with the young man’s recent publications—Linnaeus had sent copies from Hartekamp—and while the Jardin had no intention of replacing its own venerable Tournefort system with Linnaeus’s vegetable letters, Jussieu was at least intrigued enough to extend a warm welcome.

Since Linnaeus understood French no better than Dutch, he and Jussieu continued to communicate in Latin, establishing a cordial friendship that would continue via correspondence for the rest of their lives. Linnaeus spent every day of the next month with Jussieu, who not only gave him the run of the Jardin but organized (and paid for) excursions to the countryside surrounding Paris. These included trips to the royal gardens of Versailles and Fontainebleau, off-limits to the public, where Jussieu called in favors to give him access to some of the rarest plants in France. This cordial treatment came as a great relief to Linnaeus, who knew that his sexual system had received a mixed reception in different countries. English botanists, initially wary of the system—one called Linnaeus “the man who has thrown all botany into confusion”—were beginning to embrace it. Most German botanists, on the other hand, remained openly hostile, rejecting it as uselessly artificial. “I have never pretended that the method was natural,” Linnaeus wrote in appeasement to one German professor. “Become yourself a creator of a similar system, and I will immediately acknowledge you…. PEACE BE WITH US!”

Through Jussieu, Linnaeus came to understand that the current reception of his sexual system in France lay somewhere in the middle. The general consensus was that while it should not replace the native Tournefort system, the ingenuity of its author should be applauded and encouraged. In their years of correspondence that followed, Jussieu would prompt Linnaeus not to rest on his laurels, but to continue seeking a truly natural botanical system.

After overstaying his planned visit by several weeks, the “prince of botany” reluctantly prepared to depart Paris. As a parting gift Jussieu brought him to the Louvre meeting rooms of the Académie des Sciences, where to his delight Linnaeus was inducted as a foreign correspondent. He would later vastly inflate this polite mark of professional courtesy, claiming that the academy’s president begged him to stay and “become a Frenchman,” with full membership and a generous stipend, an offer he said he turned down because it would have entailed learning French. In truth he had a fiancée waiting for him in Sweden, and her dowry was the only foreseeable source of income for the near future. Still, he found it hard to part with Jussieu, and particularly hard to leave the Jardin du Roi. It was a brilliant institution, he believed. If only a similar one could arise in Sweden.

When Jussieu introduced Linnaeus to the savants of the academy, Buffon was not among them. Regular attendance at the academy’s meetings was a requirement of membership, but Buffon insisted—and would insist, for the rest of his life—on departing Paris for Montbard every August, returning only in April the following year. He was there at that moment, preparing the first French translation of Isaac Newton’s Method of Fluxions and drafting a preface that addressed one of the most quarrelsome questions of the day: Who had invented calculus, Newton or Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz?

While Leibniz had been the first to publish on the subject in 1684, Newton’s private papers showed his own discoveries in the field dating back as early as 1666: The work Buffon was translating dated back to 1671. Leibniz and Newton had corresponded with each other, and there was ample evidence that the German, with the help of mutual friends, had read at least some of the Englishman’s unpublished notes and manuscripts. But their methodologies were slightly different, which seemed to indicate something more nuanced than mere plagiarism. The dispute raged long after the death of both men, becoming both an investigational matter and a metaphysical one: Did the right of “discovery” belong to the first expression of a concept, no matter how crude, or to the expression that, through elegant clarity, best revealed an underlying truth of the universe?

Buffon, who idolized Newton, argued passionately in his favor. His argument was lopsided at best—he knew very little about Leibniz’s goals and professional context—and would in time be supplanted by a general consensus that both men had discovered calculus independently. But the effort underscored his reputation as a rising star of French savantry. Voltaire, a fellow pro-Newtonian, was particularly impressed. “I am the lost child of a party of which Monsieur de Buffon is the head,” he wrote. “He pleases me so much that I would like to please him.”