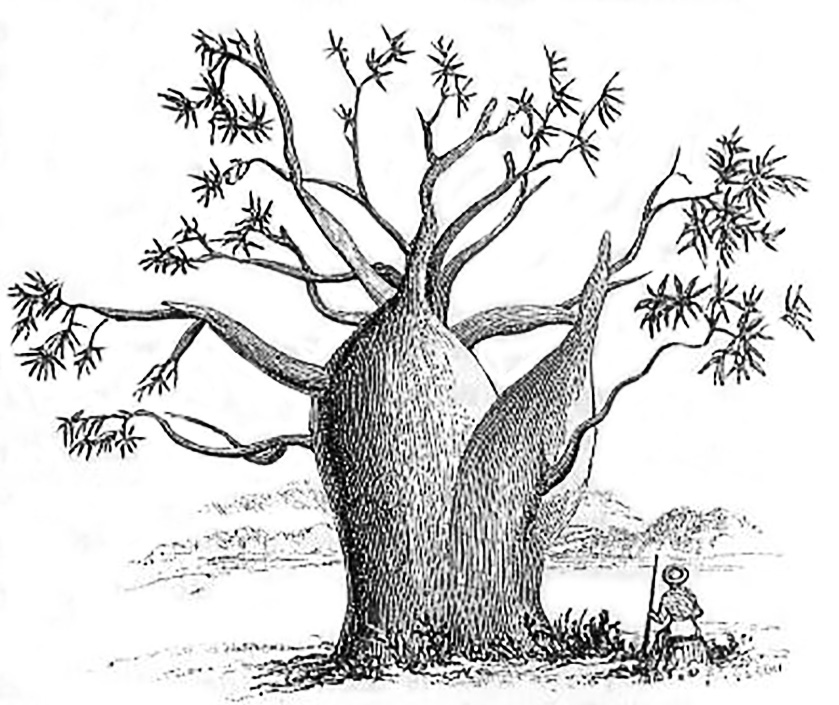

Adansonia digitata

Sixteen

Baobab-zu-zu

Buffon did not recruit apostles, but the prodigy Michel Adanson became one nonetheless. Born in 1727, Adanson had shown early signs of brilliance, mastering Latin by the age of seven, Greek by nine, and artfully translating Horace’s lyric poetry at eleven. But by then he was also facing a hard truth: He was the eldest of ten children, and his father worked as a minor attendant in the household of the Archbishop of Paris. The Archbishop was charitably paying his tuition at a conventional school, but he expected the boy to end his education at the age of thirteen and enter training for the priesthood. For the next two years, knowing his family could afford no other path, young Adanson made the most of his remaining time in the classroom, resigning himself to a future far more limited than his abilities. Then he discovered that the gates of the Jardin swung open for everyone, welcoming even a precocious thirteen-year-old boy to its formal grounds and informal courses of instruction.

Adanson began spending as much time there as possible. The staff grew accustomed to the sight of a small redheaded boy, looking even younger than his years, occupying a seat in the auditorium, roaming the Jardin’s green paths, and asking increasingly sophisticated questions. By fourteen he was a valued volunteer assistant to Bernard de Jussieu, accompanying him on specimen-hunting forays around the Paris countryside. By fifteen, he’d been spending so much time in the Jardin library that a visiting British botanist gave him the present of a small microscope, an expensive rarity at the time. “Young man, you have studied enough of the books,” the visitor said. “Your future path will be among the works of nature, not of man.”

Adanson took the hint. His ambition turned beyond the Jardin walls to the possible glories of the unknown. As far as he was concerned, Europe had few remaining surprises to offer the field naturalist. The true lodes of discovery were at least a continent away.

France had thus far launched only a single scientific expedition, the Geodesic Mission of 1735 to measure the circumference of the Earth, and it had ended in failure—nearly a decade later, several members of the mission (including Jussieu’s younger brother, Joseph) had yet to return. In 1748, with no other way to finance his travels, Adanson signed on as a bookkeeping clerk in the Compagnie des Indes, a French mercantile group that maintained a trading post in Senegal, on the West African coast. The job paid almost nothing, but the distant posting exuded adventure. “Senegal is of all white settlements the most difficult to penetrate, the hottest and most unhealthy to live in, the most dangerous in all respects,” Adanson announced, “and so known the least to naturalists.”

The Adanson who left was a bookish, unworldly twenty-year-old. The one who returned to the Jardin in 1754 was not only six years older but a man transformed. As one description noted,

He was…robust and healthy. He enjoyed dancing and was a good swordsman, a fine pistol shot, and a smart rider, having had a long training while in Africa in all those sports. He wrote that his blood was impetuous and swift, causing him to expend his energies in physical activities. He appreciated Gluck, ballet, and the opera. He was far from disdaining the attractions and charms of the ladies.

This swashbuckling figure also brought with him an astonishing trove of specimens: 350 birds, 40 quadrupeds, 600 insects, 700 shells, 400 fossil snails, 600 dried plants, and the seeds of 1,000 species. Much of it was utterly new to European science. He’d also collected hundreds of samples of minerals, resins, and exotic woods, logged astronomical observations, charted maps, and compiled a dictionary of the indigenous Wolof language.

Adanson moved in with the Jussieus, who had room to spare in their house on Rue des Bernardins, a fifteen-minute walk from the Jardin. To thank them, he prepared a special luncheon. As the Jussieus and five other invited guests looked on, he opened a box and removed several large, delicate objects packed in thick vegetable grease. He wiped off the grease to reveal African ostrich eggs, which, after several minutes of admiration, were whisked off into the kitchen to provide a memorable meal.

Adanson had enthralling stories to tell. He spoke of weeks of walking across desert sands so arid and hot that “the blood oftentimes opened itself a passage through my pores, which the sweat could not pervade,” and of witnessing, but unfortunately not preserving, a serpent whose head was “the same size as that of a crocodile…more than wide enough to swallow a hare, or even a pretty large dog, without having any occasion to chew it.”

Other stories reflected Adanson’s marked changes in perspective. He’d arrived in Senegal sporting white stockings, knickerbockers, and a standard version of European condescension toward the natives. In time, both his appearance and attitude vastly changed. He let his hair grow long, nearly to his waist, tucking it up in his hat when necessary. The stockings grew dirty, tattered away, and were not replaced.

His walls of prejudice eroded as well. A turning point came on an evening in October of 1751, when his Senegalese guides joined him in admiring the night sky. He was startled when they pointed out not only constellations but several planets as well. “Nay, they went so far as to distinguish the scintillation of the stars, which at that time began to be visible to the eye,” he recalled. “With proper instruments and a goodwill, they would become excellent astronomers.” By the end of his stay he was a committed advocate for native rights, fiercely opposing the slave trade.

He’d emerged with a second epiphany. While always aware of Buffon’s quarrel with Linnaeus, he’d kept his distance from the matter, knowing Jussieu’s friendly relations with Uppsala and mindful of Linnaeus’s self-appointed power to bestow species names. From Senegal he’d shipped Jussieu cuttings from a curious tree the locals called Baobab, adding in a cover letter, “I leave you the freedom to communicate the character of the Baobab to Mr. Linnaeus…. I further ask you to kindly ensure that this learned man learns of the infinite esteem I have for him and his works.” Linnaeus did name the species Adansonia digitata, but by the time Adanson learned of this he no longer cared. The overwhelming diversity of life he’d witnessed in Senegal had convinced him: Buffon was right. “As soon as we leave our temperate countries to enter the torrid zone,” he concluded, “there are always plants, but they have attributes so new that they elude most of our systems, whose limits hardly extend beyond the plants of our climate.” In short, Linnaeus’s neatly nested boxes of hierarchies were incapable of grasping life’s true profusion.

The returned Adanson had a new purpose in life. He wished to devise a means of organizing life that maintained the complexist mindset, one that avoided the systemists’ errors of over-simplicity and sweeping generalization. After all, it was theoretically possible to construct “an instructive and natural method,” as Buffon had written. All that was necessary was “to place together those things which resemble one another and separate those which differ.”

If the individuals resemble one another perfectly, or if the differences are so slight that we have difficulty perceiving them, they will be of the same species. If the differences begin to be perceptible but there are still greater similarities than differences, the individuals belong to a different species but the same genus as the first. And if the differences are yet more marked, without, however, exceeding the resemblances, then the individuals will not only belong to another species but even to a different genus than the group to which the first and these second group belong. They will, nonetheless, belong to the same class, because they have more resemblances than differences.

To Buffon, a complexist taxonomy was possible but impractical, at least given the present state of technology. Differentiation would need to be made not in the manner of Linnaeus, via an arbitrarily selected handful of physical characteristics—it would have to be “all-inclusive,” relying on as many characteristics as possible. In other words, a detailed knowledge of each organism, inside and out, was required: Otherwise, how could we find differences we didn’t even know to look for? Yet in-depth knowledge of many organisms was an unachievable goal in the eighteenth century. In an era when only the shells of mollusks tended to survive transportation from distant countries, when microscopes were insufficiently powerful to discern minuscule details, “one sees clearly that it is impossible to establish one general system, one perfect method, not only for the whole of Natural History, but for even one of its branches.”

But perfection was not necessary. Adanson had begun to see an approximative path toward taxonomy. “I have found a manner of describing, very different,” he wrote, “not only because it includes absolutely all different parts of the natural body, but also in that it describes these parts in all the qualities that are their own.” Adanson’s vision was a system that took meticulous account of multiple characteristics, internal as well as external, and weighted them accordingly on a spectrum of difference. It would be complicated, and arduous to compile: Determining a species would seem more like a calculus equation and less like looking up a name and address in Linnaeus’s directory. Yet Adanson thought it could be done, and that the result would be closer to the true natural system that even Linnaeus admitted was lacking in the botanical component of his work. Retiring the Linnean hierarchy by replacing it with something better might be a lifetime’s work, but Adanson felt confident that he was the person to do it.

No one in the Jardin was about to discourage him. After all, he was their fondly regarded prodigy all grown up, returning with the largest bounty of specimens ever gathered by a naturalist on a solitary expedition. He had twelve years of experience in natural history under his belt, yet was teeming with youth and vitality, even charisma. He had the support of Buffon, who praised Adanson’s collection as a “precious assemblage…worthy to be acquired by the King” and would ultimately quote him more than a hundred times in the pages of Histoire Naturelle. If anyone was going to dismantle the nested boxes of Systema Naturae, it was hard to imagine someone better suited to the task. Meeting in the Louvre in 1756, the Académie des Sciences approved the opening phase of his planned construction of a complexist taxonomy. “Let us multiply observations,” he wrote in the introduction to his manuscript, “and not systems or books, which do more to increase the confusion in natural history than to instruct.”

The following year, Adanson published the first volume of his Histoire Naturelle du Senegal, a preliminary work analyzing some of the specimens in his collection (which Buffon was still negotiating to purchase on behalf of the king). After six more years of work he published Familles des Plantes, a two-volume debut of what remained a work in progress. His use of weighted characteristics in Familles was still too tentative to evince much reaction, but the same could not be said for his unveiled system of reforming taxonomical names. It operated on three principles, which he dubbed the “rules of appointment.”

The first one: Use the historically oldest name for a species you can find. That meant reverting Linnaeus’s Actea back to the original ancient Greek term, Akokorion. But it also meant using indigenous names from the region of discovery. “Some modern botanists call barbarians…all the names Foreigners, Indians, Africans, Americans, and even those of some European nations,” Adanson noted. “But if these Dogmatic Authors had traveled, they would have recognized that in these various countries our European names are treated alike as barbarians; they are such in relation to their way of pronouncing, as theirs are ours. Let us therefore judge otherwise the acceptance of such an improper term, and let us agree that all these names put in the balance are equivalent to each other, and that they should be adopted whenever they are neither too long nor too harsh or too difficult to pronounce.”

The tree Linnaeus had named Adansonia in his honor? Baobab, the term he learned from the Senegalese, should be its formal name. “This is what made Monsieur de Buffon rightly say that the study of the appointment or modern nomenclature in Botany, is longer than the knowledge of Plants in itself,” Adanson wrote. “So we consider it superfluous to quote anything other than the oldest or best primitive name.”

He proposed taking the name of the “family” of plants (a name he preferred to genus), then adding an ingenious alphabetical code. The first species of baobab described would have the vowel a suffixed to it: Baobab-a. The next four would have the remaining vowels attached in succession: Baobab-e, Baobab-i, Baobab-o, Baobab-u. After that, the suffix would incorporate a cycle of consonants, preceding the vowel: Baobab-be, Baobab-ke (the c was changed to k for universal pronunciation), Baobab-de, et cetera. As he pointed out, this was a means of listing up to 110 species within a genus while keeping their names short, adding only two letters and one syllable. (He did the math wrong, counting 80.) He believed that would suffice for most botanical families, but the method stayed concise even if extended. Adding just two more letters of his twenty-one-letter phonetic alphabet produced 11,025 distinct variations, ending in the species name Baobab-zu-zu. That was not only pronounceable; one could look at it and know it had been discovered more recently than Baobab-zu-ka. In the tradition of Buffon, each species would also have a table of all historical names attached to it, sorted by rough chronology.

The second rule: Name a genus after its most common or best-known species. That was what earlier naturalists had done, after all, creating groupings like Pinus (pines), Acer (oaks), and the like. That would help the average person to begin conceptually zooming in on a species in question, as opposed to Linnaeus’s practice of choosing opaque names.

The third and final rule: Standardize spellings and pronunciation. Since a name would be spoken and written by people around the world—people who speak very different languages—the names should be made easy to speak and write for everyone. This meant “to write as we pronounce, to delete letters which do not ring, to join together those which have the same sound.” If a name contained silent letters, such as Herba, it should be streamlined to Erba. If it contained a letter that should be pronounced like another letter—the soft g of gentle, for instance, which sounds like a j—the letter most associated with that sound should be substituted. If a name uses the same letter twice in succession, as in Buffonia, simply eliminate one.

Linnaeus was swift in his dismissal. “I saw the natural method of Adanson,” he wrote to a colleague, soon after the second volume of Familles des Plantes was published in 1764. “There is nothing more silly…. He gives copious notes, but nevertheless distinguishes nothing. He changes all names into worse ones. I wonder whether he be sane or sober.” In other letters that year he continued to rail against the upstart (“He spoils and destroys, contrary to nature”), ultimately concluding,

Adanson’s method is the most unnatural possible…. All my generic Latin names have been deleted and instead come Malabar, Mexican, Brazilian, etc., names which can scarcely be pronounced by our tongues…. No one of his classes is natural, but a mixture of everything.

Adanson remained undeterred, both by Linnaeus’s dismissal and by the lackadaisical public reception of the work. As with any system, the proof would be in its population. With any luck, an instructive and natural method might be readied by the tenth volume, when Buffon planned to tackle the vegetable kingdom—the perfect occasion to retire Linnaeus’s admittedly artificial sexual system.

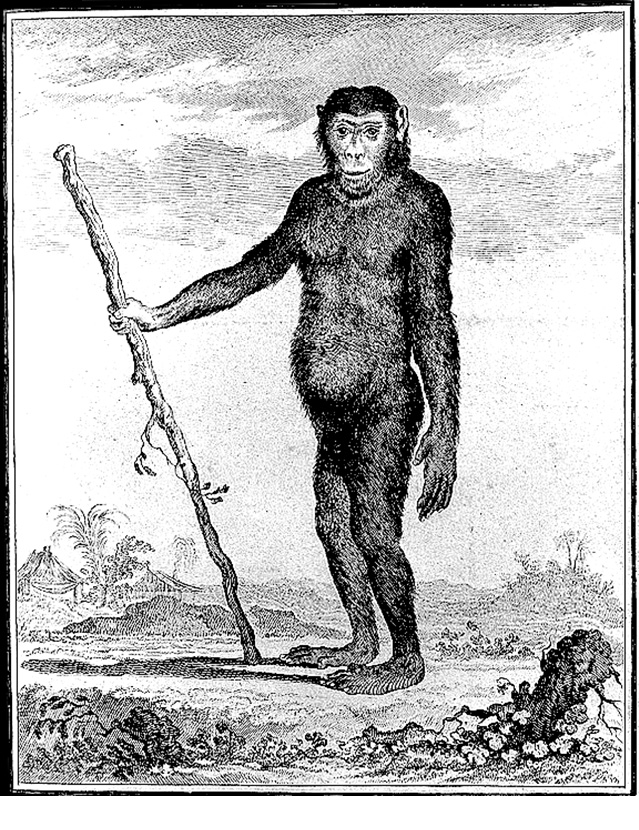

Jocko, Buffon’s chimpanzee

The master plan for Histoire Naturelle, however, was already undergoing modifications. Originally, the fourth and fifth volumes were to describe “all the Quadrupeds, and all the animals living [both] on land and in water.” The sixth one would turn to fishes. But over the course of 544 pages, volume four examined only the horse, the donkey, and the bull. Volume five, published in 1755, devoted 311 pages to the sheep, the goat (and Angora goat), the pig (including the boar), and dozens of varieties of dogs. Volume six, published the following year, took 343 pages to cover cats, deer, hares, and rabbits.

There were a lot of quadrupeds yet to go. Compounding the process was Buffon’s insistence on examining an actual, living creature whenever possible, converting portions of the Parc Buffon into a private menagerie and spending freely to populate it. He paid 1,200 livres—roughly the equivalent of Linnaeus’s annual salary—for a single Angola colobus monkey, imported from the African interior. He likely paid still more for his chimpanzee, which he named Jocko, and an unnamed lion that occupied a specially designed deep pit. Cages were detrimental to his purpose of observing animals in as natural a state as possible, and he was not averse to letting the more tranquil species roam freely across the grounds. Visitors report watching badgers pad indoors to warm themselves by the fireplace, a hedgehog helping himself to food in the kitchen, and the Angola monkey wreaking havoc in a reception room. Servants shooed them away and cleaned up in their wake, but only when Buffon’s examining eye turned elsewhere.