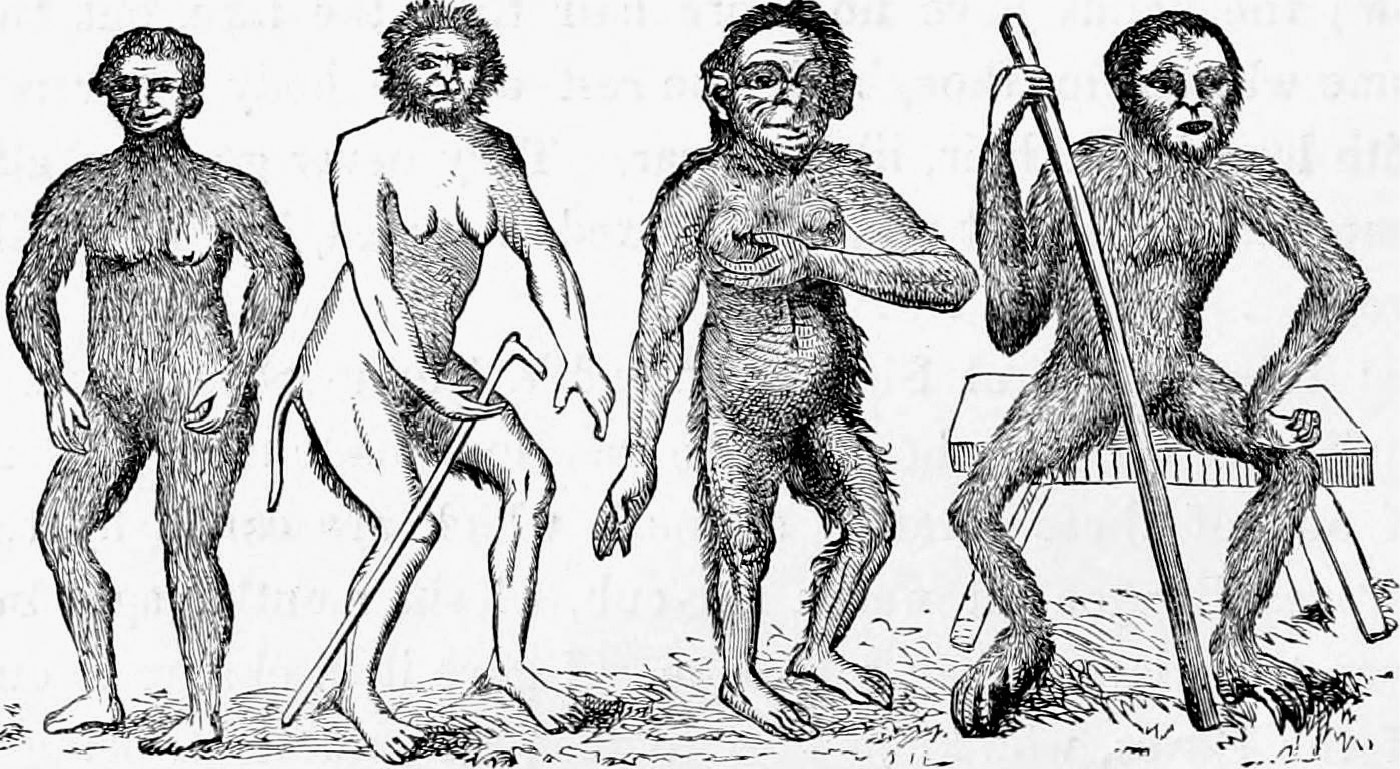

Linnaeus’s Homo nocturnus, Homo caudatus, Homo sylvestris, and Homo troglodtyes, 1758

Eighteen

Governed by Laws, Governed by Whim

Buffon’s chief critique of the Linnean system—that it was inherently arbitrary—seemed to find validation in 1758, when the system arbitrarily changed. That year, Linnaeus published the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae, which listed 4,236 animal species and completed the application of binomial names to all animals, complementing his binomial naming of plants. All in all, it was “a work which for a knowledge of nature has no equal,” as Linnaeus congratulated himself in his journal. Yet the effort had left him exhausted and depressed. “My hand is too weary to hold a pen,” he confided in a letter to a friend. “I am the child of misfortune. Had I a rope and English courage I would long since have hanged myself…. I am old and grey and worn out.” He was, at the time, fifty years old.

In the first edition of Systema Naturae, Linnaeus had coined the term Fauna as a companion to Flora. In the tenth, Linnaeus forged still more language to encapsulate his concepts. Among the now-common words that he coined was Cactus, for the order of prickly plants. He adapted it from the Greek word kaktos, which at the time referred only to a species of Spanish artichoke. Lemur, from the Latin word for “spirits of the dead,” a reflection of the creature’s nocturnal habits and unsettling stare. Aphid, for the genus of tiny insect: As he never explained the reason for this name, its etymology remains a mystery. Other names coined by Linnaeus in this edition did not remain solely scientific names but entered the common usage of modern language: absinthe, azalea, amaryllis, tanager, boa constrictor.

There were near-poetical acts of language encapsulated in the names themselves. Linnaeus, a lover of chocolate, named the cocoa plant Theobroma cacao, or “food of the Gods.” But there was also gibberish. Linnaeus had originally used Alcedo, Latin for “kingfisher,” for the genus of kingfishers. But as the category grew he decided to split Alcedo into two separate genera. To name them, he made two anagrams of the original term, labeling them Lacedo and Dacelo. The words were nonsensical but “sounded” right.

There were numerous reassignments of species, which retained their names but were shifted from one genus to another, evidence to Buffon that the system had been on shaky ground in the first place. Of the mongoose, he observed, “Monsieur Linnaeus made it first a badger, then he made it a ferret…others make it an otter, and others a rat; I cite these ideas…to put people on guard against these appellations that they call generic, and which are almost all false, or at least arbitrary, vague and equivocal.”

But those were minor adjustments. Far more notable were the major revisions. Linnaeus now moved worms and insects into separate orders, and not all water dwellers were lumped into the category of “fish.” The class of Quadrupedia (four-legged), which was now extended to include elephants, sea cows, whales, and all hoofed animals, was renamed Mammalia, from the Latin mammalis, or “pertaining to the breast.”

A categorical relabeling was long overdue—whales and sea cows were indisputably not four-legged—but switching to lactation as the defining characteristic was a jarring move, and easily criticized. “A general character, such as the teat, taken to identify quadrupeds should at least belong to all quadrupeds,” Buffon responded, pointing out that male horses do not have nipples (nor, for that matter, do male rats) and that the ability to produce milk was usually only a temporary condition in the lifecycle of a species. Identifying a newly discovered species as a mammal would be cumbersome—one would have to make sure they were observing a female specimen actively nurturing offspring. But Linnaeus was only interested in using the number and position of teats as one of several grouping characteristics at his disposal. To seize on “some small relationship between the number of nipples or teeth of these animals or some slight resemblance in the form of their horns” struck Buffon as nothing less than “violence.”

Yet the most consequential changes were Linnaeus’s extensive renovations to the order Anthropomorphia. Retiring the tautology of “man-like,” he renamed it Primates, or “of the first or highest rank.” Buffon did not object to the implicit value judgment; he too had needed to tread lightly when including humans in the animal kingdom. “Man is a reasonable being, and animals are creatures without reason,” he’d written in Histoire Naturelle, before gingerly piercing the barrier between the two: “Although the works of the Creator are in themselves all equally perfect, the animal is, according to our way of perceiving, the most complete work of Nature, and man is the masterpiece.”

But within the order Primates, the genus Homo displayed dubious changes. Two years earlier, in the ninth edition of Systema Naturae, Linnaeus had at last applied binomial nomenclature to the human species, naming it Homo diurnus, or day-dwelling man. Now he renamed it Homo sapiens, or wise man (the description remained know yourself). Previously the genus Homo held only one species, but now Linnaeus felt compelled to give it company. While Homo diurnus had disappeared, there was now a Homo nocturnus (night-dwelling man), Homo caudatus (tailed man), Homo troglodytes (cave-dwelling man), Homo sylvestris (forest man), Homo ferus (wild man), and Homo monstrosus.

The crowded genus would last only for this edition. Homo troglodytes would be reclassified as Simia satyrus, the chimpanzee. Homo sylvestris would become Pongo pygmaeus, the orangutan. Homo ferus would be discontinued, as it represented not a separate species but incidents of humans raised in the wild. Homo monstrosus would likewise fade, as Linnaeus had used it to file away miscellaneous oddities, from the rumored giants of Patagonia to a reported “large-headed, horned” denizen of China. But Homo nocturnus and Homo caudatus were products of Linnaeus’s own imagination.

Such errors were fleeting. Others were lasting, and profound. Linnaeus had originally said only that “man varies,” sorting humanity into the vague, unspecified categories of White European, Red American, Tawny Asian, and Black African. Now he added deeply detailed—and profoundly prejudiced—descriptions:

Homo sapiens americanus

Red-colored, choleric, erect. Hair black, straight, thick; nostrils wide, face harsh; beard scanty. Stubborn, cheerful; free. Paints himself with the red lines of Daedalus.

Governed by customs.

Homo sapiens europaeus

Fair, sanguine, brawny. Hair yellow, flowing. Eyes blue. Gentle, acute, inventive. Covered by close vestments.

Governed by laws.

Homo sapiens asiaticus

Sallow, melancholic, strict. Hair blackening. Eyes dark. Severe, haughty, greedy. Covered by loose vestments.

Governed by opinions.

Homo sapiens afer

Hair black, contorted. Skin silken. Nose snub. Swollen lips. Women shameful of bosom [i.e., on display]; breasts long-lactating. Sly, slow, careless. Anoints self thickly.

Governed by whim.

Linnaeus sought to encode such sweeping characterizations as universal qualities, aspects of identity as real as the needles of an evergreen or the hooves of a horse. Later apologists have attempted to absolve Linnaeus of racism, pointing out that he did not specifically use the term race, nor did he declare one type superior to others. This is specious. In 1758, the word race was a fluidly applied collective term, demarcating any group one wished to consider as a whole—a usage that persists today in the term the human race. Defining one group as “governed by laws” and another as “governed by whim” could not be a more blatant assertion of superiority. And unlike Homo nocturnus and Homo caudatus, these concoctions did not disappear. Their author would stand by them for the rest of his life.

Linnaeus believed many things that later admirers have chosen to ignore. He was convinced that epilepsy was caused by washing one’s hair, that the liberal application of aquavit to a puppy’s fur would cause it to remain a miniature dog, and that swallows slept through winter at the bottom of frozen lakes. These and other pronouncements, confidently stated but absent verification (Linnaeus, unlike Buffon, was not an experimenter), were at least confined to his minor writings. In the pages of his magnum opus, embedding equally unmoored conclusions was a spectacular act of ignorance masquerading as savantry.

It was also an act with enormous consequences. Humans’ practice of objectifying other humans on the basis of physical characteristics is, of course, ancient, and the xenophobic prejudices encapsulated in what we now term racism date back to human prehistory. But the modern conception of races—along with the spurious pseudoscience of assigning innate characteristics to them—has a genealogy that can be traced directly to the pages of Systema Naturae.

Buffon’s work was moving him in the opposite direction. As the ephemeral new members of the genus Homo demonstrated, Linnaeus’s notions of what constituted a species were more vague than ever, but they still centered on physical appearance. In the first volume of Histoire Naturelle, Buffon had stated that while physical descriptions were important, “care must be taken against losing one’s way in such a number of minor details…while considering too lightly the main and essential things.” Physiological details varied with individuals, and “the history of an animal ought not to be the history of the individual, but that of the entire species,” he cautioned. True natural history was “to depict things simply and clearly, without changing or oversimplifying them, and without adding anything to them from one’s imagination.”

He’d listed twelve factors he considered more important than appearance in defining a species. Now, after years of firsthand observation of his private menagerie, Buffon was more convinced than ever of the validity of that list:

Their generation (creation of live young)

The duration of pregnancy

Their nature of birth

Their number of young

Their care by their fathers and mothers

Their type of rearing

Their instinct

Their place of habitation

Their tricks

Their way of hunting

The services that they can render us

All the uses and commodities that we can obtain from them

Such multiple datapoints certainly helped him paint vivid verbal portraits in the pages of Histoire Naturelle. Yet taken as a whole, they fell short of usefully identifying a species; it was immensely impractical for field naturalists to standardize observation of all twelve. A breakthrough came when he realized that the first four qualities were interrelated: Generation, pregnancy, birth, and litter size could be seen as aspects of the same process, which he dubbed reproduction. It was in reproduction, then, that Buffon saw a practical species concept. “It is neither the number nor the collection of individuals who confirm the species,” he wrote, “but the constant and uninterrupted succession of individuals who reproduce.” Although species remained a “general and abstract word,” it now seemed possible to approach a working definition. Not by examining a single specimen but a long chain of them, extending backward and forward in time.

It is by comparing nature today to that of other times, and current Individuals to past Individuals, that we have taken a clear idea of what is called species; and the comparison of the number or likeness of Individuals, is only an accessory idea and often independent of the first…. The Donkey looks more like the Horse than the Barbet to the Greyhound, and yet the Barbet and the Greyhound are one and the same species, since they produce Individuals who can themselves produce other.

Were there not species that could interbreed? Yes, but only for a generation. Buffon had cited the horse and the donkey because, bred together, they produced a mule—a sturdy creature longer-lived than the horse and more tractable than the notoriously stubborn donkey. Yet mules are sterile: Each one must be born of a male donkey and a mare. An offspring of the opposite combination (female donkey and stallion) is possible, but rare. Called the hinny, it is equally sterile. But what of other animals? Were some capable of producing fertile hybrids, but simply did not do so because they had more compatible mates at hand?

The same year that Linnaeus published his tenth edition of Systema Naturae, Buffon published in the seventh volume of Histoire Naturelle a record of his ongoing experiments in cross-breeding, reporting on “a female wolf I kept three years, [who] although shut up alone in a large pen with a mastiff of the same age, was not able to accustom herself to living with him, nor to submit to him.” He would spend years on similar experiments, enforcing the cohabitation of male and female cross-species pairs—dogs and foxes, hares and rabbits, pigs and peccaries, goats and sheep. It was only the last of these pairings that produced results: nine hybrid offspring, seven male and two female. Yet none of the goat-sheep could be bred to produce a subsequent generation. Like the mule, they were sterile.

Buffon would have had similar results had he tried interbreeding large cats. We now know that jaguars and lions can interbreed, despite the former being native to the Americas and the latter to Africa. Pumas, leopards, and tigers can also interbreed with both the jaguar and the lion, creating some very interestingly named hybrids: liger, jaguleps, pumapards. All are single-generation creatures, unable to reproduce.

Buffon had his working definition. The essence of species lay in reproduction, the ability of one generation to propagate another. He logically applied this measure to humanity: Since all ethnic groups seemed clearly capable of interbreeding with one another, they comprised a single species. “The dissimilarities are merely external, the alterations of nature but superficial,” he concluded. “The Asian, European, and Negro all reproduce with equal ease with the American. There can be no greater proof that they are the issue of a single and identical stock than the facility with which they consolidate to the common stock.” In sum, reproduction was proof that

there was originally but one species, which, after being multiplied and diffused over the whole surface of the earth, underwent diverse changes from the influence of the climate, food, mode of living, epidemical distempers, and the intermixture of individuals…that at first these alterations were less conspicuous, and confined to individuals; that afterwards, from continued action, they formed specific varieties; that these varieties have been perpetuated from generation to generation.

Buffon was not free of prejudicial assumptions. He considered it likely that the earliest humans were relatively light-skinned, concluding that “blanc appears to be the primitive color of Nature.” But he would later amend this statement, hypothesizing that the earliest humans were dark-skinned Africans. And while the French word blanc is most commonly translated as white or pale, Buffon applied the term to a broad array of ethnicities. Inhabitants of the Barbary mountains in North Africa, of the northern provinces of Persia, and of the middle provinces of China—he described them all as blanc, making it clear he was referring to a far more diverse group than Linnaeus’s Homo sapiens europaeus. Buffon’s theory was that our species arose in a climate that the human animal finds most comfortable, namely “the most temperate climate [that] lies between the 40th and 50th degree of latitude.”

To some extent this reflected a cultural bias: Those latitudes include Italy, Switzerland, and of course France. But Buffon was not pointing to those countries. He was demarcating a geophysical band stretching around the Earth—one that includes parts of North Africa and the Mediterranean Sea, Turkey, Ukraine, broad swaths of North America, most of Mongolia, the aforementioned middle provinces of China, and a generous portion of Japan. Indeed, Buffon considered Asia the likely origination point of human civilization, calling it “the ancient continent” and stating that Japanese and Chinese culture “is of a very ancient date…. Their early civilization may be ascribed to the fertility of the soil, the mildness of their climate, and the vicinity of the sea.” In later pages of Histoire Naturelle he would make his point even clearer, writing that Europe “only much later received the light from the East.”

Before the foundation of Rome, the happiest countries of this part of the world, such as Italy, France, and Germany, were still only peopled by men who were half-savages…. It is thus in the northern countries of Asia that the stem of human knowledge grew; and it was upon the trunk of the tree of science that was raised the throne of man’s power.

Declaring just four varieties of humans (or subspecies; Linnaeus was never clear on the matter) was to Buffon an error of the highest magnitude. To affix inherent attributes to them was repugnant. Defining Homo sapiens asiaticus as “severe, haughty, greedy” was a grave disservice to our cultural forebears. Homo sapiens afer struck him as particularly ridiculous. Calling those of African descent “sly, slow, careless” served only to justify their exploitation, which Buffon adamantly opposed. “Their sufferings demand a tear,” he wrote. “Are they not sufficiently wretched in being reduced to a state of slavery; in being obliged always to work without reaping the smallest fruits of their labour, without being abused, buffeted, and treated like brutes?”

Humanity revolts at those oppressions…. How can men, in whom the smallest sentiment of humanity remains, adopt such maxims, and on such shallow foundations attempt to justify excesses to which nothing could ever have given birth but the most sordid avarice? But let us abandon those callous men, and return to our subject.