A bust of Buffon in his seventies

Twenty-two

The Price of Time

While Buffon surely noted the passing of his rival, almost none of his private writings during this period survive. He was still in the habit of burning all his papers once he was through with them, and he had much to burn. At the age of seventy-one, he was busier than ever. Eleven years earlier, after the considerable investment of nearly half a million livres, he’d opened an ironworks in Buffon, his namesake hamlet near Montbard. Serving as both a foundry and a research center into metallurgy, the ironworks had grown to employ more than four hundred workers, casting cannon for the French army and navy alongside experimental items, such as the ornate iron fencing Buffon installed in the Jardin. As one of the first attempts at private large-scale industrial manufacturing in France, the Buffon ironworks were a template for factories to come. They were also quite profitable. Buffon poured some of the profits into acquiring adjacent properties and expanding the Jardin, trusting that the king would eventually compensate him for the expenditures. (He would be disappointed.)

He’d also entered into his most prolific phase as a writer. In just three years he’d produced five more volumes of Histoire Naturelle, bringing their total number to fifteen. From that he at last turned away from the subject of quadrupeds, commencing his survey of birds. He began by constructing an aviary in Montbard, this time not in the Parc Buffon but adjacent to his manor. The location was a gift to his wife, who enjoyed the soundscape of birdsong.

Buffon was also continuing to boost the careers of younger natural historians. One notable patronage began in September of 1764, when a man named Philibert Commerson arrived at the gates of the Jardin, humbly inquiring after a job he’d been offered seven years earlier. Born to a prosperous middle-class family, Commerson was a physician who’d never bothered to practice, having attended the Montpellier medical school in southern France chiefly to take botany classes. He’d made an early name for himself in botanical circles, but not an entirely positive one—he had a reputation for brilliance but also for flouting authority. Instead of asking for permission to take cuttings from the university botanical gardens, he’d simply helped himself. When caught and banned from the grounds, he’d climbed over the fence at night and continued adding to his collection.

Still, his research had earned the attention of Linnaeus, who commissioned him to write a study on Mediterranean fish, and Jussieu, who offered him a place at the Jardin du Roi. He’d quickly fulfilled the commission but turned down the job, preferring instead to botanize in the French and Swiss countryside.

The next seven years did not go well. Commerson’s family began to withdraw their financial support. He suffered multiple injuries during his field studies—falls from rock-climbing, near-drownings in torrential streams, and ultimately a severe dog bite that left him bedridden for three months (he would walk with difficulty for the rest of his life). In want and in pain, Commerson agreed to his family’s hastily arranged match with a woman seven years his senior. They attempted to start a family. She died in childbirth, at the age of forty-one.

Now thirty-six years old, Commerson quietly departed for Paris, accompanied by a single family servant. He rented a second-floor apartment on the Rue des Boulangers, a few blocks away from the Jardin, where Jussieu informed him that, regrettably, the offered position had long since been filled. But Buffon welcomed him nevertheless, giving him the run of the Jardin, introducing him into the social circles of Parisian savantry, and sponsoring him two years later, when the botanical opportunity of a lifetime arose.

The opportunity began with the unhappiness of Louis Antoine de Bougainville, a decommissioned French army colonel who loathed being remembered for the lowest point of his military career: surrendering Montreal to the British during the Seven Years’ War. After that war, after a defeated France had ceded almost all of its territory in North America, Bougainville used his own funds to help 150 colonists relocate from French Canada to a group of islands off the coast of South America, in a settlement he named Port Saint Louis.

It was an expensive achievement, and quickly dismantled. After returning to France, Bougainville learned that the nascent colony was seen as a threat by Spain, who considered it a prime location to stage attacks against Spanish holdings on the mainland. King Louis XIV, aware that the British probably agreed, decided to sell the island chain to Spain rather than risk the costs of having to defend it. Bougainville was ordered to sail back to the archipelago (which Britain would indeed later claim as the Falkland Islands) and hand it over to Spain.

Bougainville did not particularly relish adding another surrender to his record. He proposed making the voyage grander in scale, transforming it from yet another French concession into a triumphal act. No French ship had ever circumnavigated the globe. What if he sailed to South America, turned over the islands, and just kept going? It would be a prideful achievement, but more important a covert scouting mission for heretofore-unknown lands that France could claim as territories. To mask this intent, Bougainville suggested making it a scientific expedition.

The king, receptive to the suggestion, reached out to the Jardin to provide a suitably intrepid naturalist. Buffon steered the appointment to Commerson, who eagerly accepted, asking only permission to bring along Jean Baret, his longtime servant and assistant. There were no objections. The expedition, consisting of two ships, the Etoile and the Boudeuse, departed on November 15, 1766.

On board ship and at ports of call, Jean Baret struck his fellow expeditionaries as exactly the sort of assistant the slightly built, sickly Commerson needed. In his mid-twenties, sturdily built, and strong, Baret earned the nickname “Commerson’s beast of burden” and the admiration of Bougainville, who wrote of him “carrying, even on those laborious excursions, provisions, arms and portfolios of plants with a courage and strength.” Working in tandem, Baret and Commerson collected or documented so many specimens that Commerson was struck by the implications on Linnean taxonomy. “What presumption to lay down the law as to the number of plants and their characters in spite of all the discoveries which are yet to be made,” he wrote. “Linnaeus only proposes some 7,000 to 8,000…. I venture to say however that I have already made by my own hand 25,000, and I am not afraid to declare that there exist at least four or five times as many species on the whole world’s surface.”

In April of 1768, after successful specimen-collection stops in Brazil and Patagonia, Bougainville’s two ships crossed the Pacific, reached the Society Islands, and dropped anchor in Tahiti. They were only the second group of Europeans to visit the Polynesian archipelago: The British ship HMS Dolphin had passed through just ten months earlier. Upon learning that the British had not staked a claim, Bougainville promptly claimed the islands for France, naming the region New Cytheria.

When the expedition arrived, one of the first Tahitians to come aboard the Etoile was a young man named Autourou. Instead of being impressed by the formal uniforms of Bougainville and his retinue, Autourou saw Baret among the crew assembled on deck and began circling in fascination, saying “Aiene, aiene.” The next day, when Commerson and Baret were onshore collecting specimens, they found themselves surrounded by Tahitians looking at the assistant with wonder and again repeating “Aiene.” One of the strongest among them stepped forward, picked up Baret, and began to carry him away. An officer of the Etoile drew his sword and pursued, thwarting the abduction and compelling the expeditionaries to puzzle out what was going on.

Aiene, they soon gathered, meant “female.” Unaware of the clothing and behavioral conventions that Europeans associated with gender, the Tahitians had immediately recognized what had passed unnoticed by Bougainville and company during the months of voyage: Commerson’s valet was not Jean but Jeanne. “With tears in her eyes [she] admitted that she was a girl,” Bougainville wrote, “that she had misled her master by appearing before him in men’s clothing at Rochefort at the time of boarding…. When she came on board she knew that it was a question of circumnavigating the world and this voyage had excited her curiosity. She will be the only one of her sex [to do so] and I admire her determination.”

Philibert Commerson and Jeanne Baret

The statement that she had “misled her master” was a lie, and soon unraveled; Commerson and Baret had been lovers for years. They’d even had a child together not long after arriving in Paris, a son they named Jean-Pierre, who’d died a few months later. The ruse had been planned from the beginning by them both. The double deception—of Baret’s gender switch and Commerson’s pretended ignorance—roused the anger of their fellow expeditionaries. It marked Commerson as a criminal: It was illegal for a woman to sail aboard a French vessel. To the relief of Bougainville, they disembarked shortly thereafter on the island of Mauritius, where the two at last lived openly as a couple. Commerson happily continued to acquire specimens both on Mauritius and the island of Madagascar, until his health began to fail. Baret tended to him until he died in 1773, at the age of forty-five. Two years later, Baret returned to France, in the process becoming the first woman to circumnavigate the globe.

Baret brought with her Commerson’s collection of specimens, which by now contained thousands of species entirely novel to European savantry. Buffon could have summarily confiscated the collection in the name of the king, but instead he insisted on treating Baret respectfully, entering into negotiations for the collection’s sale. They settled on a price that allowed her to live comfortably until her death in 1807.

Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu

Buffon assigned the collection to the Jardin du Roi, conveying it into the care of another protégé: Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu, the twenty-nine-year-old nephew of Bernard de Jussieu, who’d arrived from Lyon as a teenager and taken a medical degree before installing himself in the Jardin. While living with and caring for the aging Bernard, he’d been surprised to learn that the elder Jussieu had given up on waiting for Linnaeus to develop a natural system of botany and had begun quietly developing one himself. Bernard had made significant progress, going so far as to lay out a garden at Versailles according to his new taxonomy, but with characteristic modesty had refused to publish even a brief description of his principles. The garden was eventually plowed over, and the project languished until 1772, when his nephew Antoine-Laurent decided to take it up. Unlike his friend Adanson, the younger Jussieu was more deferential than defiant in his opposition, admitting only to “not being wholly Linnaean” and calling Linnaeus himself “a great man.” Yet he was convinced that botany deserved an alternative to Linnean systematics, which, he wrote, “seem to keep science away from its true goal.” He was still working on a Jussieu System when his uncle Bernard died in 1777, just two months prior to Linnaeus’s passing. The Commerson-Baret collection came into his hands soon afterward, and his progress accelerated.

That same year, Buffon released his fourth and fifth volumes on birds, and a fifth volume of “suppléments” to earlier portions of Histoire Naturelle. One of these supplements was in truth a direct revisitation of Earth’s deep history—the same subject he’d used to begin the series, and the subject that had drawn the angry censure of theologians and the Sorbonne. In an essay entitled The Epochs of Nature, he divided the history of the Earth into seven “epochs,” clearly intended as counterparts for the seven days of biblical creation. He did not specify the time period for each epoch, as he could not—no technology existed for accurately measuring geological time. But the essay’s radical claim remained clear: Earth’s history far exceeded the brief span enumerated in the Old Testament.

Buffon began by assuming the role of his inevitable critics. “How could you reconcile, one might say, such a great age that you give to matter, with the sacred traditions, which provide for the world only some six or eight thousand years?” he wrote. “To contradict them, is that not to lack respect to God, who had the goodness to reveal them to us?” On the contrary, he argued, “The more I have penetrated into the heart of Nature, the more I have admired and profoundly respected its Creator. But a blind respect would be superstition.”

Let us try to hear reasonably the first facts that the divine Interpreter has transmitted to us on the subject of creation; let us collect with care the rays that have escaped from that first light; far from obscuring the truth, they can only add a new degree of luminosity and of splendor.

The first epoch, he wrote, began with the creation of the solar system. He theorized that the Earth and other planets were accreted masses of matter ejected from the sun at approximately the same time, since all “circle around the sun in the same direction, and nearly all in the same plane”—a theory that, in broad strokes, remains predominant today. Earth’s second epoch began when it solidified, coalescing into a dense, rough spheroid. In the third, Earth became an ocean planet (“for a long time the seas covered it entirely, with the possible exception of some very high ground”); the fourth began when the waters retreated and “the lands raised above the waters became covered with great trees and vegetations of all kinds,” Buffon wrote. “The worldwide sea was filled everywhere with fish and shellfish.”

Then life arrived on land. The fifth epoch dawned “when the Elephants and the other animals of the South lived in the north,” and the sixth was marked by the separation of the continents. The seventh and current epoch was the age of humans, or more specifically “when the power of man has assisted that of Nature.”

The Epochs of Nature represented Buffon’s final attempt to break the lens of fixity, and as such it was a calculated provocation. He anticipated a backlash, which came in November of 1779 when the Sorbonne once again formally denounced him and began censure proceedings. The theology faculty formed a committee to take up the question, but this time Buffon had the tacit support of the king himself. Louis XVI trod lightly amid the academic indignation, quietly requesting only that the committee “proceed with circumspection,” but this had the effect of stopping them in their tracks. The committee never issued a report. The Sorbonne nevertheless prepared a new retraction for Buffon to sign, one very similar to the retraction he’d put his signature to twenty-eight years earlier. Again, he gladly signed it, and again promised to incorporate the retraction in the next volume of Histoire Naturelle.

This time he did not keep his promise. In fact, he went so far as to republish The Epochs of Nature as a separate volume, the better to reach the widest possible audience. Wary of pressing the point further, the Sorbonne published his retraction themselves in a brochure (written in Latin) in 1780. “When the Sorbonne picked petty quarrels with me, I had no difficulty in giving it all the satisfaction that it could desire,” he confessed to a friend. “It was only a mockery, but men were foolish enough to be contented with it.”

“No man has known the price of time better than the Count de Buffon,” one relative observed. “No man has employed, more constantly or with more uniform purpose, all the moments of his life.” Yet in the spring of 1782, the formidably busy Buffon stopped in his tracks. A special visitor had arrived at the Jardin, and Buffon wished to give him his full attention.

The visitor was Carl von Linné the Younger, now forty-two years old and well into his tenure as his father’s successor. Buffon had never met the senior Linnaeus in person, but here was an unprecedented opportunity to defuse the old perceptions that he had been the father’s nemesis and perhaps forge a form of peace. He welcomed the son effusively, insisting on being his personal tour guide and directing that they wander undisturbed, that “on that day he would be spoke to by none but him.” As assistants rushed to clear the Jardin paths and the rooms of the Cabinet, their tour began.

The occasion was the professor’s first trip out of Sweden in an official capacity, a circuit of courtesy calls to prominent naturalists in Denmark, the Netherlands, and now France; London would be next. It was a junket, but a welcome respite for von Linné. His life back in Uppsala bordered on the miserable.

A taller, thinner version of his father, von Linné was generally well liked as a person and respected (albeit grudgingly by some) for gamely doing his best to fulfill familial expectations. But as a teacher, he could not step to the podium without revealing his limitations. “His delivery was fluent, but mixed with a certain cold indifference,” one lecture audience member reported. “It appeared as if his exertions were rather a performance of the duties of his station, than a real zeal flowing from a natural fondness of his science.”

Even before his father’s death, he’d made a botch of Uppsala’s academic politics. In 1777 he petitioned the king of Sweden to assume the last of his father’s duties by becoming a full professor. Owing to his father’s worsening condition the petition had been granted, but by appealing directly to the king he’d gone over the head of the university’s chancellor, which angered both the chancellor and his colleagues, who called him behind his back a “wretched boy” and a “lazy loon in a superlative degree.” The task of simply maintaining his father’s collection was exhausting: He was fighting off rats, wood mice, moths, and molds until he complained he was “as tired as a day laborer.” But worst of all was his domestic situation. While never warm to her husband, the Widow von Linné positively hated her bachelor son. “It was singular that the lady of Linnaeus should have had so particular an aversion,” one visitor to the household wrote. “He could not have had a greater enemy in the world than his own mother…. Her only son lived under the most slavish restraint and in continual fear of her.” Humiliated on almost all fronts, he considered his role the hollowest of legacies.

“Poh! My father’s successor,” he privately grumbled to a friend. “I would rather be anything else. I would rather be a soldier.” Still he plodded on, albeit slowly. Despite his announced intention to update his father’s Systema Naturae and its sub-catalogues, he had thus far only completed a Supplementum, a single volume intended to augment both Genera Plantarum and Species Plantarum.

For Buffon, getting to know Professor von Linné carried at least a pang of sadness. For all the indications that the younger man was struggling to walk in his father’s footsteps, he was at least an undisputed successor. Buffon was attempting to construct a similar legacy for his own son. It was a battle he’d already half-lost, and he seemed on the verge of losing it completely.

On that afternoon in 1782, Buffon had been a widower for thirteen years. His wife, Marie-Françoise, had been severely injured in a riding accident in Paris, suffering a disfiguring jaw injury that kept her immobilized and in pain for almost three years. When she died at the age of thirty-seven, the grief-stricken Buffon formally mourned for the next two years; he would never remarry. Instead he devoted himself to raising their only child, Georges-Louie-Marie Buffon, universally known as Buffonet.

As Linnaeus had done with Carl the Younger, Buffon sought to anoint Buffonet as his successor from the start. Linnaeus had enrolled his son at Uppsala University at the age of nine; Buffon had succeeded in convincing King Louis XV to promise that Buffonet would inherit his position as intendant of the Jardin, even though the boy was only five years old at the time. The attempt at a dynasty only lasted two years. In February of 1771, Buffon had been struck down by an attack of dysentery so virulent he was expected to die at any moment. The king’s assurances had been for sometime in the distant future; Buffonet at the time was still only seven. Under these circumstances other ambitious men began jockeying for Buffon’s job, and the king began to listen. In between bouts of agony, Buffon learned that the arrangement was suspended. His successor would not be his son but the Count d’Angvillier, a rank amateur in matters of natural history.

Buffon did not die. He rallied back to health, much to the embarrassment of the king, who felt exposed to criticism at court for having jumped the gun. To save face he made Buffon a count, creating the title by declaring that Buffon’s holdings in Burgundy comprised a county in themselves. As an additional honor, the king awarded the newly ennobled Comte de Buffon the status of royal attendant, allowing him to enter the royal bedchamber instead of requesting formal audience. The king, however, did not retract the future appointment of the Count d’Angvillier. Buffon was now an aristocrat, but it had come at a bitter price.

He continued to raise his son as the prodigy of natural history he wished him to be. While Buffonet might not be destined to run the Jardin, he could still carry on the work of the Histoire Naturelle. Yet despite twelve years of private tutors and his father’s personal instruction, Buffonet displayed neither the intellect nor the inclination to engage in the subjects at hand. He pranked his tutor by spraying ink across his shirt. Sent off on a tour of European capitals, the boy dined privately with Catherine the Great of Russia, an admirer of the senior Buffon. The occasion prompted Catherine to observe “the strange irony by which men of genius seem fated to father sons who are virtual imbeciles.” Now eighteen, the handsome but shallow Buffonet was likely to be found anywhere but in the Jardin.

Buffon and Linnaeus the Younger walked the earthen avenues formed by the spaces between plant beds, and past ubiquitous identification labels that disproved the rumors that Buffon had suppressed Linnean botanical names (they were prominently displayed, alongside Tournefortian ones). As they entered the Cabinet du Roi, the visitor could not help but notice the building’s centerpiece, a feature his host found personally embarrassing. It was a heroic statue of Buffon himself.

To Buffon’s dismay, the statue had been the second of the king’s expiatory gestures for reneging on his promise to Buffonet. It was ordered as a surprise, with the commission given to Augustin Pajou, one of the foremost sculptors of the day, at the significant cost of fifteen thousand livres. The secret project took six years to complete, and was installed while Buffon was away at Montbard. “It would have given me greater pleasure if it were installed only after my death,” he confided. “I have always thought that a wise man must rather fear envy than attach importance to glory.” As he’d written in Histoire Naturelle’s fourth volume:

Glory…becomes no more than an object without appeal for those who have come close to it, and a vain and deceitful phantom for others who have remained at a distance from it. Laziness takes its place, and seems to offer easier paths and more solid benefits to everyone, but disgust precedes it and boredom follows it. Boredom, that sad tyrant of all things that think, against which wisdom can do less than madness.

Buffon was not immune to flattery, but there was a line between flattery and glorification. Though confident of his historical importance, he was also well attuned to public relations. He sensed that the statue would be seen as a sop to his ego, even though he had not commissioned it, posed for it, or even authorized its existence. When he finally saw it in person, his suspicions were confirmed.

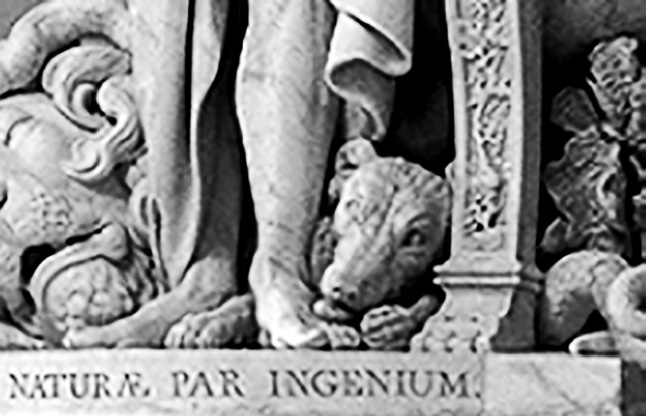

Detail of statue

The Buffon it depicted was nearly nine feet tall, heroically muscular, and, in the words of one contemporary, “absolutely naked, enveloped only by a drapery to conceal from view those parts which modesty orders one to hide.” The figure holds a stylus in his right hand, seemingly poised to write upon a tablet propped upon a globe of the Earth. The overall pose evokes Moses receiving the Commandments. Beneath the globe sponges grow, representing the vegetable kingdom. The animal kingdom is represented by a lion, either dead or insensible, a serpent winding through his mane, and a sheepdog. A cluster of crystals, representing the mineral kingdom, grow by the lion’s head. In a touch later described as an “unfortunate marriage of actual and symbolic,” the sheepdog is earnestly licking the toes of Buffon’s bare left foot.

In the third volume of Histoire Naturelle, Buffon had written a description of the (male) human animal:

He carries himself straight and tall, his attitude is that of command, his head looks to heaven and presents an august face on which is printed the character of his dignity. The image of the soul is painted there by his physiognomy, the excellence of his nature breaks through his material organs and animates the features of his face with a divine fire.

Augustin Pajou, the sculptor, seems to have intended to bring this passage to life, with Buffon as the embodiment. But the idealized image was already proving to be more of an embarrassment than even Buffon had imagined. The original inscription at the base had been Naturam amplectitur omnen, “He embraces all of Nature,” but persistently reoccurring graffiti added Qui trop embrasse mal étreint, “He who embraces all, grasps poorly.” At the time of Linnaeus the Younger’s visit, the inscription had recently been removed and a new one substituted: Majestati Naturae par Ingenium, “A genius to match the majesty of Nature.” Buffon doubtless did not linger long in the statue’s vestibule, instead hurrying into the Cabinet itself, where he and his guest whiled away several companionable hours.

Professor von Linné departed in a hail of pleasantries, pleased to have been treated with far more respect than he’d been accustomed to back in Uppsala. But he could not help being awed. Much expanded by Buffon’s methodical acquisitions of adjacent properties (often using his own money), the Jardin now extended over 110 acres. The Uppsala botanical garden comprised 11 acres. Its only staff was a part-time gardener; Buffon employed more than a hundred. His cabinet occupied a single small outbuilding, and it certainly bore no towering statue of his father.

The two never saw each other again. Von Linné the Younger returned from his tour nine months later with a case of jaundice, contracted in London, and died the following year. On November 30, 1783, his body joined his father’s under the floor of Uppsala Cathedral. After the funeral oration, attendees bore witness as the family coat of arms was broken into pieces, in accordance with Swedish tradition. Since there were no male survivors to assume the Riddarklassen title, the House of von Linné ceased to exist.

There were, however, female survivors. As Linnaeus Junior had never married, his inheritance reverted to his mother. This included the entire collection of specimens, which Linnaeus Senior had considered his most valuable bequest. “Let no naturalist steal a single plant,” he’d written in his will. “Invaluable as they are, they will increase in value as time goes on. They are the greatest the world has ever seen.” Linnaeus Junior had taken this injunction seriously. Not long after his father’s funeral he’d turned down a wealthy Englishman’s offer of twelve thousand pounds for the collection, a decision that may have explained some of his mother’s animosity toward him.

Faced with the costs of ushering her two remaining daughters into respectable marriages, Sara-Lisa von Linné was unsentimental about selling off the family’s chief asset. She reached out to the English collector, but he was no longer interested. The best price she could muster was from another Englishman, an amateur naturalist who offered slightly more than one thousand pounds. It was a fraction of the original offer, but the widow could pry no higher price from any other interested parties. The deal was done, and on September 17, 1784, the British brig Appearance sailed from Stockholm, carrying twenty-six crates from Uppsala in its cargo hold.

It was time for Buffon to grapple with his own mortality. Outwardly, he was still a fine physical specimen. A visitor to Montbard in 1785 described him as “looking at age seventy-eight like many do at fifty-six or fifty-eight…a man of large stature, with a very happy physiognomy, brown eyes, black eyebrows, a thick head of hair, white as snow.” But unknown to all but a few intimates, his famously rigorous routine was now being interrupted by excruciating attacks of abdominal and lower back pain, and agonizing urination. Buffon was suffering from nephrolithiasis, more commonly known as kidney stones. His solitary habits had thus far allowed him to conceal his attacks, but they were increasing in frequency, often bringing his work to a standstill.

As to the work itself, no end loomed even on the distant horizon. To Buffon it was patently obvious that even under the best of circumstances, he’d never live to see the completion of the Histoire. It was time to choose a successor.

He’d abandoned hoping that it might be Buffonet, now twenty-one. Buffon had at last let his son become a soldier, purchasing for him an officer’s commission in the elite Gardes Française. He’d also facilitated Buffonet’s marriage to the daughter of the Marquise de Cepoy, a match that came with a generous dowry. Buffon added an extravagant stipend of twenty thousand livres a year and wished the couple well.

Georges-Louie-Marie Buffon, known as Buffonet

Yet Buffon, like Linnaeus, had a far more capable offspring. Visitors to Montbard often found themselves attempting to avoid staring at Monsieur Lucas, Buffon’s young assistant, for two reasons. For one, he was exceptionally handsome. “He was remarkably tall and had features of great regularity,” as one guest described him. But moreover “the distinction of his form and the beauty of his face made him look, very strongly, like the native son of Buffon.”

The suggestion that the resemblance might be coincidental was pure politesse. It was unspoken but long accepted that Monsieur Lucas was in fact Buffon’s son, the result of a liaison with a village woman. Unlike his half-brother, he was an adept manager, a gifted horticulturalist, and a man of the outdoors. Buffon trusted Lucas to manage the Montbard estate for several years before relocating him to the Jardin, where Lucas occupied an apartment in the Cabinet building. There, Lucas became the de facto intendant while Buffon was away, holding the purse strings and executing his father’s plans. But Buffon could not publicly acknowledge him as his son, nor train him as his successor.

Who, then, would carry on the work of Histoire Naturelle?

It would not be Michel Adanson. While he had once annoyed Buffon by openly lobbying to become his successor, by now he was enmired in a project of his own. In 1775, Adanson had presented to the Académie des Sciences a plan to extend his complexist taxonomy across twenty-seven volumes of “a Natural Method comprising all known beings,” followed by an eight-volume continuation of The Natural History of Senegal, then “a Natural History Course, a Universal Vocabulary of Natural History to serve as a basis for the universal order, then of a collection of 40,000 figures of 40,000 species of known beings, and finally a Collection of 34,000 species of beings preserved in my office.”

This was, as everyone but Adanson himself recognized, monumentally overambitious: The task would be greater than the lifelong toils of Buffon and Linnaeus combined. Buffon had attempted to make him see reason, counseling Adanson to dial back his ambition, but he could not be persuaded. The academy, naturally, voted not to fund the project. Adanson had vowed to undertake it nonetheless, at his own expense. In the eight years since, his dogged insistence on being the vast work’s sole author had taken him away from the Jardin. When his manuscripts and specimens overflowed his rooms at the Jussieu house, he’d left it for larger quarters in a cheaper, more distant neighborhood. With no income other than a meager pension Buffon had arranged for him through the academy, he attempted to make ends meet by privately teaching botany.

Students came rarely, and rarely lasted long. He was still welcome at the Jardin—Buffon made sure of that—but the crush of work and the indignity of encroaching poverty had turned him into something of a recluse. Overwhelmed by sheer volume, his effort to develop a complexist taxonomy came to a standstill. The task of constructing an alternative to Linnean systematics was now the sole purview of Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu, years into the project of building upon his late uncle’s work. Unwilling to interrupt that work, Buffon did not consider the younger Jussieu a candidate to succeed him.

Bernard-Germain-Étienne de La Ville-sur-Illon, Comte de Lacépède

The winning candidate would be Bernard-Germain-Étienne de La Ville-sur-Illon, the Comte de Lacépède, born in Gascony in 1756. Buffon could see similarities between the young count and himself: Lacépède had inherited his fortune (and in his case, a title) from a childless great-uncle on his mother’s side. Like Buffon, he grew up dividing his time between a rural estate and his province’s capital. A recent entry to the circle of Jardinistes, Lacépède was only twenty-seven, and he had grown up obsessively reading Histoire Naturelle.

In 1784, Buffon appointed Lacépède as curator and assistant demonstrator in the Jardin, on the understanding that the young man would study to become his literary successor as well, practicing to write in Buffon’s distinctive style. This was important: Buffon not only wanted Lacépède’s volumes to blend seamlessly with his, he believed that style itself was critical to Histoire Naturelle’s success. “Style is the only passport to posterity,” Buffon had written.

It is not range of information, nor mastery of some little known branch of science, nor yet novelty of matter that will ensure immortality. Works that can claim all this will yet die if they are conversant about trivial objects only, or written without taste, genius and true nobility of mind.

Most important, Lacépède shared his core philosophy: It took discipline to perceive nature in all its complexities. The urge to tame such complexities through oversimplifying, by seeing demarcations when none existed, was a human failing, and ultimately a human blindness. Lacépède understood the distinction between the mask and the veil—between imposing order and patiently waiting for nature to reveal what it would. With any luck, Lacépède would pass this understanding on to his own successor, and that successor would do the same in turn. It was now apparent that the Histoire Naturelle might best be considered a multi-generational project, extending well into the nineteenth century if not beyond.

Buffon had made his peace with that realization, with knowing that his life’s work would comprise not a monument in itself but a foundation for others to build upon. After four decades of unstinting discipline he’d failed to achieve his goal, yet the effort left him more awestruck than disappointed. “Far from becoming discouraged, the philosopher should applaud nature,” he wrote, returning to his metaphor of the veil.

Even when she appears miserly of herself or overly mysterious, and should feel pleased that as he lifts one part of her veil, she allows him to glimpse an immense number of other objects, all worthy of investigation. For what we already know should allow us to judge of what we will be able to know; the human mind has no frontiers, it extends proportionately as the universe displays itself; man, then, can and must attempt all, and he needs only time in order to know all.

Buffon’s own time, he knew, was running out.

In May of 1784, while walking the streets of Philadelphia, Thomas Jefferson noticed an unusually large panther skin hanging from the door of a hatter’s shop. The forty-one-year-old Jefferson bought it on the spot, determining, as he put it, “to carry it to France, to convince Monsieur Buffon of his mistake with this animal, which he had confounded with the Cougar.” He was in town waiting for a ship to take him to the Continent, where he was about to succeed Benjamin Franklin and become the American republic’s second ambassador to France. Yet to him, a posting to France meant entering the domain of the great Buffon, and he most earnestly wished to make his acquaintance.

For one, his predecessor was one of Buffon’s dearest friends. Franklin and Buffon had grown so close that other Frenchmen, wanting Buffon’s attention, often first approached the American ambassador. But also among his many other interests, Jefferson considered himself something of a naturalist. In fact he was working on a book on the subject at the time: Notes on the State of Virginia, the only book Jefferson would publish. As soon as the first printing of two hundred copies emerged from a Paris press, he bundled a copy with the panther skin and sent both on to Buffon.

In January of 1786, he received an acknowledgment:

Monsieur De Buffon offers his thanks to Mr. Jefferson for the animal skin that he was kind enough to send him. Would his health have permitted he would have conveyed his thanks in person, but as he cannot travel, he hopes that Mr. Jefferson would enjoy coming…to enjoy a meal in the garden.

This cougar differs from the one that was supplied by a Monsieur Coliunou, in that the body is shorter…it also has a shorter tail, and so it seems to fall in the middle between Coliunou’s cougar and the South American variety.

By referring to it as “the animal skin” and later “this cougar,” Buffon was pointedly refuting the reason Jefferson had sent it in the first place: He did not believe it to be a panther skin, as he did not believe panthers existed in North America. (He was correct; even the so-called Florida panther is actually a cougar.) Nevertheless, the invitation was too tempting to turn down. It was a long journey from Paris to Montbard, particularly for a single evening, but Jefferson was curious to see both the great man and the park that had become his natural element. He gladly accepted.

“It was Buffon’s practice to remain in his study till dinner time, and receive no visitors under any pretense,” Jefferson observed, “but his house was open and his grounds, and a servant showed them very civilly.” Whiling away his time wandering through the gardens, he caught a glimpse of his host deep in thought, pacing down another path. He knew better than to acknowledge Buffon’s presence, as that was standard protocol. Their formal meeting came that evening, when Buffon entered the dining room in his characteristic full finery. “I was introduced to him as Mr. Jefferson, who, in some notes on Virginia, had combated some of his opinions,” the ambassador reported. “He proved himself then, as he always did, a man of extraordinary powers in conversation.”

The two men were amiable but did not exactly mesh. Buffon, who abhorred slavery, was all too aware that Jefferson was a slave owner. Buffon had also read Notes on the State of Virginia, and was quite aware that while Jefferson had praised him as “the best informed of any naturalist who has ever written” in its pages, he’d also spent a good bit of the book directly rebutting one passage from Histoire Naturelle, in which Buffon had written “the animals common both to the old and new world are smaller in the latter, and that those peculiar to the new are on a smaller scale.”

To Buffon this had seemed a reasonable observation. The large cats of Africa and Asia—lions and tigers, and yes, panthers—were larger than the reported large cats of the Americas. The European bison is larger than the American one. There were no American equivalents of the giraffe, nor of the elephant.

Ah, but there was an American elephant, Jefferson contended. The incognitum or mammoth, whose fossilized bones were on display at the Jardin: Those had been unearthed in Kentucky. True, no living mammoths had yet been captured, but the American wilderness was large, and largely unexplored. Surely they would eventually turn up. Jefferson did not believe in extinction, not because of religious orthodoxy but because it struck him as too extreme for the subtleties of nature. (Fourteen years later, then-president Jefferson would dispatch the Lewis and Clark Expedition with standing instructions to shoot and preserve portions of any living mammoths they might encounter.)

Buffon was in no mood to explain his conception of deep time. “Instead of entering into an argument,” the American recalled, “he took down his last work, presented it to me, and said, ‘When Mr. Jefferson shall have read this, he will be perfectly satisfied that I am right.’ ” Jefferson does not record the volume. Since at the time Buffon was publishing Histoire Naturelle’s survey of minerals, it seems likely “his last work” refers to the most recently published supplementary volume, which includes the following passage:

This communication of elephants, from one continent to another, must have taken place through the northern lands of Asia neighboring America…. One can thus presume, on some basis, that the eastern seas beyond and above Kamchatka are not very deep. And, one has already seen that they are littered with a great number of islands.

In other words, Buffon envisioned a time when the separation of continents was not quite complete. The Old and New Worlds, he speculated, had once been connected by a land bridge stretching from the Kamchatka peninsula, of which only the Aleutian Islands remained. Numerous species, including humans, had likely migrated across this land bridge. Over vast expanses of time—enough for the land bridge to disappear—the migrated species adapted to the new climates of the Americas. The incognitum, however, could not. (Buffon was right, but only in the broader sense; it now seems likely that mastodons could not “adapt” to the increased hunting of human population growth during the Pleistocene.)

Still contentious, Jefferson told Buffon that he had conflated two different species into one, the American deer and the European red deer. “I attempted…to convince him of his error…. I told him our deer had horns two feet long; he replied with warmth, that if I could produce a single specimen, with horns [antlers] one foot long, he would give up the question.” He also found the count “absolutely unacquainted” with another North American animal, the moose. Buffon thought it was a kind of reindeer. Jefferson assured him they were a completely different species, and that “the reindeer could walk under the belly of our moose.” That North America could produce an animal so large was, of course, difficult for Buffon to believe. Jefferson pointed out that Pehr Kalm, Linnaeus’s American apostle, had mentioned the moose’s enormous size, but this did not quite convince Buffon; Kalm had been known to exaggerate.

Jefferson had to leave it at that. It was exactly 9:00 p.m. Buffon, sticking to the same schedule he’d maintained for more than four decades, thanked his guest and retired for the evening.

Jefferson left Montbard determined to provide Buffon with indisputable proof that North America was indeed home to mammals of impressive size. On January 7, 1786, he commissioned John Sullivan, an American friend, to obtain a freshly preserved moose. “It would be an acquisition here, more precious than you can imagine,” Jefferson wrote. “I will pray you send me the skin, skeleton and horns just as you can get them.”

In the winter of March 1787, under heavy snow, Sullivan dispatched a hunting party of twenty men to Vermont, where they shot a magnificent specimen: a moose standing seven feet tall, with antlers towering four feet higher still. It took two weeks to deliver the carcass to Boston, by which time it was rapidly decomposing. Sullivan did his best to render the bones from the flesh, but found it “a very troublesome affair” to assemble a complete skeleton. Unable to salvage the antlers, he procured another pair to “be fixed on at pleasure.” The crated-up remains were placed on a ship and transported to Le Havre-de-Grace in France, where they subsequently went missing. Jefferson called it “a proper catastrophe,” mourning that “this chapter of natural history will still remain a blank.” To his elation the boxes of moose eventually turned up, along with a staggering bill—the equivalent of about thirty thousand dollars today. Jefferson paid up, declaring the entire project “an infinitude of trouble.” Still, he took great pride in delivering the moose to the Jardin du Roi and felt vindicated when Buffon agreed to have it “stuffed and placed on his legs in the King’s Cabinet.” As he reported to Daniel Webster, the giant moose “convinced Mr. Buffon. He promised in his next volume to set these things right.”

There would be no such volume. Buffon had already published what would be his last entry on a living creature, the stub-billed penguin (“a kind of goose which does not fly”) in 1783. The next volumes were devoted to minerals, a forum he used to again assert that “petrifications and fossils” comprised the remains of living species, many of which were now extinct.

This operation of Nature is the great means which she has used, and which she still uses, to preserve forever the footprints of perishable beings; it is indeed by these petrifications that we recognize her oldest productions, and that we have an idea of these species now annihilated, whose existence preceded that of all beings now living or vegetable; they are the only monuments of the first ages in the world.

He also took a few last jabs at systematists. “Nothing has more retarded the progress of the sciences than this logomachia, this creation of new words,” he wrote in an essay on sulfur. “Such is the defect in all methodological nomenclatures,” he noted in his entry on salt. “They vanish, their inadequacy exposed, as soon as one tries to apply them to the real objects of nature.”

On March 28, 1787, Buffon’s final volume was approved for publication by the royal censor. It was a treatise on magnets, capped off with 361 pages of meticulously compiled tables documenting the declination of compass needles observed by mariners at various locations throughout history. Histoire Naturelle, Générale et Particulière now stood at thirty-five volumes—three introductory ones on general subjects, twelve on mammals, nine on birds, five on minerals, and six miscellaneous ones he entitled Suppléments. It was only a fraction of his original plan, which had been to cover “the whole extent of Nature, and the entire Kingdom of Creation” in fifteen volumes. He never touched upon amphibians, fish, mollusks, or insects. The realm of plants, for which he’d originally allocated three volumes that would bring him in sharpest contrast with Linnaeus, still awaited a viable plan of organization.

It was a staggering achievement nonetheless. Even incomplete and excluding the Cabinet descriptions (outsourced and credited to his assistant Daubenton), the Histoire comprised the most extensive nonfiction work to emerge from the pen of a single author, rivaling in size and scope encyclopedias compiled by hundreds of contributors.

Histoire Naturelle had upset far more factions than systematists and the Sorbonne. There were other ideologies, other worldviews, that Buffon had offended, particularly when he found himself unable to mask his condemnation. His excoriation of slavery (How can men, in whose breasts a single spark of humanity remains unextinguished, adopt such detestable maxims?) was difficult to ignore, particularly in the pages of a bestselling book at a time when the international slave trade was at its height. His musings that civilization had first arisen in Asia were well outside the mainstream worldview, which held that civilization was a torch passed directly from the Greeks to the Romans to contemporary Europe. He’d courted controversy in his Discours sur la Nature des Animaux, a section of the fourth volume of Histoire Naturelle, where he addressed the notion that animals had no souls. Centuries of observation, he pointed out, made it clear that animals could experience “all that is best in love,” including bonding, maternal and paternal connections, and even self-sacrifice. He could not, however, conclude directly that this proved animals had souls, since that would bring down the wrath of Catholic theologians, who assured the faithful that animals had nothing of the kind. This skirted the censors, but it made for unsettling reading: the idea that un-souled creatures were nevertheless experiencing romantic attachments. The discourse offended prudes as well as theologians, since Buffon made it clear that “all that is best in love” also included sexual attraction and gratification, an elevation of sexuality that ran against the notion of consigning it to base and shameful urges. After reading Discours sur la Nature des Animaux, the king’s mistress Madame Pompadour showed her disapproval by wordlessly swiping Buffon in the face with her fan.

Misogynists were also displeased. Elsewhere in Histoire Naturelle, Buffon unleashed a scathing attack on how men had used the concept of “virginity” to control women. “A virtue existing solely in purity of heart,” he observed, “has been metamorphosed into a physical object, in which most men think themselves deeply interested.”

This notion, accordingly, has given rise to many absurd opinions, customs, ceremonies, and superstitions; it has even given authority to pains and punishments, to the most illicit abuses, and to practices which mock humanity…. I have little hope of being able to eradicate the ridiculous prejudices which have been formulated on this subject.

This contention, that virginity was a “moral being” and not a “physical object,” meant that a woman lost her virginity when she first chose to have sex, not when it was forced upon her. He also pointed out that the so-called proof of virginity, an intact hymen, was elusive—when anatomists could find this membrane at all, he pointed out, its configuration varied so widely that it could often not be disturbed by intercourse at all. “The symptoms of virginity,” he concluded, “are not only uncertain, but imaginary.”

Buffon had even attempted to dismantle a near-universal belief: that the Earth’s abundance was unlimited. Writing of what we now call biomass in his essay “De la Terre Végetale,” he wrote, “Nature’s productive capacity is so great that the quantity of this vegetal humus would continue to augment everywhere, if we did not despoil and impoverish the earth by our planned exploitations of it, which are almost always immoderate.” The idea that humans could “despoil and impoverish” a God-given natural cornucopia was almost as blasphemous as the notion that it had not been created in a single act.

But each of the thousands of pages of Histoire Naturelle, controversial or not, was the direct production of Buffon’s unstinting application of the complexist worldview, the willingness to peer patiently through the veil of Nature rather than imposing a mask. “The true and only science is the knowledge of facts,” he’d declared in his youth. The facts had taken him in directions where he practically stood alone. He could only hope that Lacépède would summon similar discipline, and courage.

After forty-seven years of clockwork scheduling, Buffon’s springtime return to Paris seemed as predictable as the arrival of the season itself. But in early 1788, the staff of the Jardin du Roi received an unprecedented notice: The intendant had broken routine, wrapping up his Montbard affairs and preparing the transfer of his household far sooner than usual. It was still winter when a welcoming party of demonstrators, gardeners, and assorted Jardinistes assembled in the Jardin’s esplanade, watching an unfamiliar carriage pass through the gates and halt before the Cabinet du Roi. Why was the Count not arriving in his usual style, in his personal coach? That question faded at the sight of the man who emerged and stepped down haltingly, under an assistant’s hovering care.

Buffon was eighty-one years old. Advanced nephrolithiasis compelled him to walk with a deliberate gait, his customary composure occasionally broken by a wince. The carriage had been borrowed, in the hopes that its more robust suspension would better shield him from the jarring of ruts and potholes.

His condition, Buffon knew, was in its terminal phase. Unable to be removed by surgery, the kidney stones had accumulated to the point at which the kidneys themselves were beginning to shut down. The pain dominated every waking hour, and there were far too many waking hours. “Sleep had abandoned him for the last three years of his life,” his grand-nephew would later recount, and yet “the uselessness of remedies did not seem to surprise or irritate him.”

He saw his approaching destruction…with courage and resignation, without being surprised and without complaining; he calmly dictated his last dispositions. The movements of the soul did not disturb the freedom of the spirit.

“What kindness! You have come to watch me die,” Buffon said a few days later, grasping the hands of the woman arriving at his bedside. “What a spectacle for a sensitive soul!” It was a morbid jest, and one that no longer unnerved the visitor. Buffon had been welcoming her in this fashion for several mornings now, as if she hadn’t already spent the previous day sitting quietly by his side. She was Suzanne Curchod Necker, an elegant fifty-one-year-old who moved in the highest circles of Parisian society. Her husband, the former director-general of the Royal Treasury, was a wealthy banker. She and Buffon had loved each other for more than fifteen years.

Suzanne Curchod Necker

Theirs was what the French call une amitié amoureuse, an intimacy that is nonsexual but nonetheless passionate, conducted in plain sight and with the tolerance of significant others. “I love you and I will love you all my life,” he’d written, in one of the stream of letters they exchanged. “I love and respect you beyond all that I love.”

His words were well chosen. Respect, not ardency, had won her affection. The founder and formidable center of one of Paris’s most prestigious literary salons, Madame Necker had little time for those admirers who praised only her beauty and social graces while failing to acknowledge her keen, far-ranging intelligence. This had never been the case with Buffon: The great man cultivated her acquaintance with a refreshing lack of condescension, treating her not as an object of flirtation but as an intellect fully capable of sparring with his own. He sent Necker drafts of his own work to “submit to her judgement, asking at the same time that she may be indulgent and frank with him.” They argued over religion (she was a Calvinist, and hoped to convert him), exchanged ideas and confidences, and grew close.

Their relationship was conducted entirely in the open—her husband Jacques and Buffon often corresponded about “our Suzanne”—but it was indisputably one of chaste intimacy. Despite the passionate language that passed between them, neither was interested in a sexual relationship. Madame Necker was aware that her husband’s political career made him vulnerable to scandal. Buffon, still devastated by his wife’s passing (“Her death has left an incurable wound in my heart,” he confessed) was elated to pursue intimacy on an entirely different plane. “Ah, God!” he wrote to Necker. “It is not a sentiment without fire; it is rather a warming of the soul, and emotion, a movement sweeter and also quite as strong as that of any other passion. It is enjoyment without violence, a happiness more than a pleasure. It is a communication of existence more pure, and yet more real than the sentiment of love. The union of souls is a penetration, that of bodies only a contact.”

It is clear that Buffon saw her not only as an equal but in many respects a superior. “But for the union of souls, is it not necessary that they be both upon the same level, and can I flatter myself that mine will ever raise itself as high as yours?” he asked in a letter. “I think so sometimes because I wish it, because you are my model, because I love and respect you more than I have ever loved any one.”

Such feelings were reciprocated. “When I see him,” she wrote of Buffon, “my heart deceives me in two ways directly contrary to each other. I believe I am admiring him for the first time, and I think that I have loved him all my life.”

Over the years he’d confessed to her about the indignities of aging, of fading eyesight and a trembling hand that increasingly struggled to hold a pen. He’d shared his heartbreak over Buffonet’s unsuitability as a successor, and the unvarnished truth about his present suffering. It was Necker who, having immediately grasped the significance of his plans to leave Montbard early, sent her most luxurious carriage to minimize the agony of the journey. Now he was refusing all food and medicine, and she was here to hold his hand.

“I feel myself dying,” Buffon said. “You are still a charmer to me, when every other charm has gone from me.”

She remained by his bedside for five more days, until the morning when he surprised everyone by asking them to leave. He wished to make one last tour of the Jardin, in as solitary a fashion as possible. On an April afternoon, “at a time when a warmer sun was gilding the new shoots,” Necker and other friends retreated to a distance. “We could see an old man,” she wrote, “supported by two servants, wrapped in warm furs, walking for a moment in the alley trees crossing the garden.” The furs had been a gift from Catherine the Great of Russia.

The Jardin he teetered across was significantly different from the one he’d entered in 1749. He’d expanded it 450 percent, increasing the original stock of two thousand plants to more than sixty thousand. The former Cabinet of Drugs, renamed the Cabinet du Roi, now occupied not a few crowded rooms but a stately building. Buffon had tripled the staff, and doubled the courses of study available, at no cost, to anyone who wished to undertake them. He had turned the former apothecary garden into the largest institution of natural history in the world.

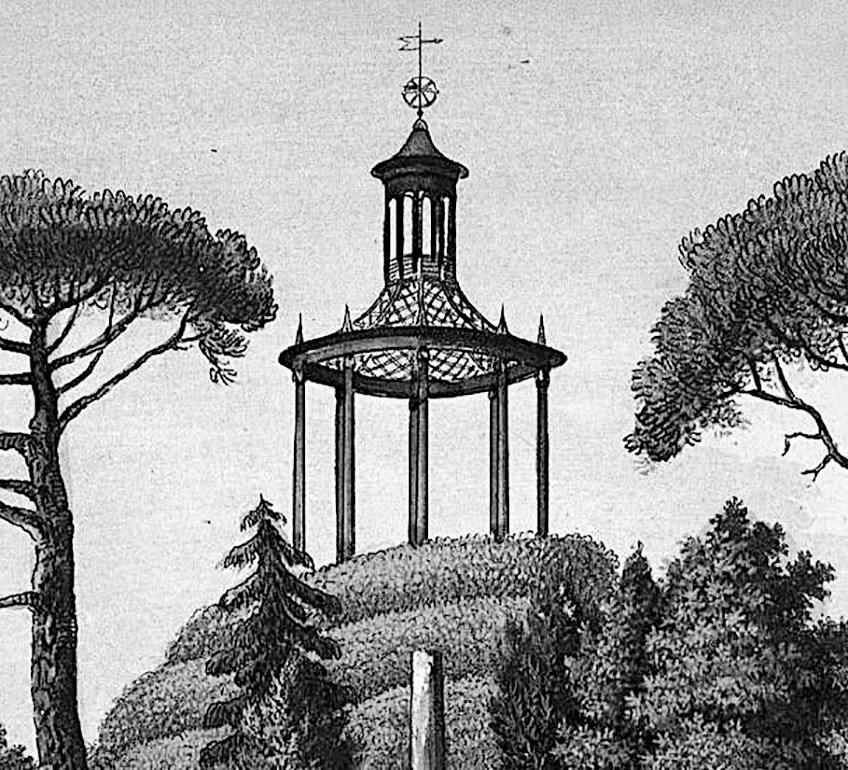

Passing summarily by the monumental statue of himself, donated by a guilty king, he took in a view of the open-air structure he considered his true monument. The highest point in the garden had been topped with a flagpole when Buffon took command of the Jardin, but in 1786 he’d made it the site of a gazebo he called the Gloriette. Cast at Buffon’s own eponymous ironworks in Burgundy, it was the first all-iron structure in Paris. It seemed to defy gravity. The slender columns were designed as a series of spear-like projections, holding to earth a cupola that was not a weighty dome but a delicate latticework that seemed woven like a basket, its own arc being pulled higher into the sky by a smaller structure surmounted by a weather vane and armillary sphere. Unlike other cupolas, which were designed to convey solidity and stolidity, the Gloriette was like the gondola of a balloon, about to take flight. It marked noon by means of an unusual mechanism: a magnified sunbeam burned through a single strand of hair holding back a counterweight. When released, a hammer in the shape of a globe struck a gong, allowing passersby to adjust their timepieces and notifying workers it was time to replace the hair. The uppermost part bore the inscription Horas non numero nisi serenas, “I count only the bright hours.”

Buffon’s Gloriette, at the highest point in the Jardin

The Gloriette’s elegant blend of simplicity and complexity would not be fully appreciated until decades later, when mathematicians noticed that the airy, net-like roof drew its solidity not only from solid iron casting but from the pattern of the lattice. It is a one-sheeted hyperboloid, considered the most complicated of quadratic surfaces yet discovered. Maximizing the ratio of structural integrity to surface area, one-sheeted hyperboloids would not enter the lexicon of architecture until the twentieth century, when they became the underlying formula for the cooling towers of power plants. The Gloriette, like Buffon, was ahead of its time.

The Jardin was thriving, and would endure. So too would Histoire Naturelle. To Buffon’s mild annoyance, his handpicked successor the Count de Lacépède was so eager to carry the torch that he’d already published a volume of his own, a work on egg-bearing quadrupeds and snakes. Buffon would have preferred that Lacépède wait until his passing, but at least he could enjoy his protégé’s praise in the introduction (“a general and immense natural work, of which his genius conceived the vast whole in such a sublime manner”), and read enough to assure himself that Lacépède’s voice on the page reasonably resembled his own, and that their philosophies remained in alignment.

Buffon was not a religious man, but “when I become dangerously ill and feel my end approaching, I will not hesitate to send for the sacraments,” he’d confided to a friend. “One owes it to the public cult.” He believed that a family priest was at his side during the evening of April 14, but he was hallucinating: It was Madame Necker who heard his last confession. “Dear Ignatius,” he said to the imagined cleric, “you have known me for more than forty years; you know what my behavior has always been. I did good when I could and I have nothing to be ashamed of. I declare that I die in the religion in which I was born.” He drank three teaspoons of Alicante wine, closed his eyes, and died at forty minutes past midnight.

In accordance with his wishes, Buffon became his final specimen. During an autopsy conducted the following day, the stones in his urinary tract were extracted and counted. There were fifty-seven, enough to overflow an adult’s cupped hand—an astonishing amount of internal shrapnel, representing an unfathomable quantity of pain. Buffon’s heart was excised and drained of blood, then given per his instructions to Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond, a geologist who had assisted him in his research on mineralogy. After a longer procedure requiring the delicate deployment of a bone saw, the autopsists removed Buffon’s brain. They measured it, assessed it as “of a slightly larger size than that of ordinary brains,” and presented it to Buffon’s son.

Buffonet did not want it. He was all too aware of how his own intellect had disappointed his father, and the prospect of a lifetime tending to the relic of his father’s brain appears to have been less than appealing. Instead, he proposed a switch: He would keep his father’s heart, while the geologist could depart with the brain. As Saint-Fond was compelled to discreetly mention, the heart was intended for another. Buffonet understood, and saw an opportunity to clear himself of the matter altogether.

Saint-Fond departed with both the heart and the brain. He placed the latter in a crystal urn and attached an engraved label reading Cerebellum of Buffon, conserved by the method of the Egyptians. (It would remain in his family for the next seventy-nine years.) Buffon’s heart, encased in gold and crystal, made its way to the private quarters of Madame Necker, the chaste love of his last years and comfort of his final moments.

“Buffon died Wednesday,” the periodical Literary Correspondence reported. “He just closed the door on the most beautiful century that could ever honor France.” The next morning, twenty thousand Parisians gathered to witness the funeral procession.

While she treasured the reliquary of Buffon’s heart, Madame Necker decided that her truest earthly memento of Buffon was not an object but a place. “I go every week to the Jardin du Roi, to pay homage to the living remains of a friend who is dear to me,” she wrote to an acquaintance. “Sometimes still his great soul rises from the midst of his ashes to commune with me. Nothing, however, can compensate me for his usual society.”

Her weekly visitations with Buffon’s great soul did not last long. Four months later King Louis XVI, desperate to stave off an impending financial crisis, appointed her husband Jacques Necker the Chief Minister of France. The following January, on her husband’s advice, the king sought popular support for fiscal reforms by reviving the ancient, nearly forgotten concept of Estates General, an advisory assemblage of representatives from the nobility, the clergy, and commoners. When the assembly provided not compliance but a list of their own grievances, the frustrated king fired his chief minister.

It was July 11, 1789. Historians point to various incidents as the inciting moment of the French Revolution, but the dismissal of Jacques Necker looms large among them. He was a popular figure, respected for his openness about the country’s near-bankruptcy and willingness to consult the populace. In Paris, street protests broke out the next day. They continued, and escalated. Two days later, protestors stormed the Bastille.