Thomas Henry Huxley

Twenty-six

Laughably Like Mine

It was no surprise that Thomas Henry Huxley and Charles Robert Darwin became friends. In many ways, their lives ran in parallel. Both had begun their scientific careers as resident naturalists on board British warships—Darwin on the HMS Beagle, Huxley on the HMS Rattlesnake—and both initially gained recognition for their papers on marine invertebrates. Huxley was sixteen years younger, but Darwin worked so slowly that their professional arcs began to intersect. When Darwin won a medal from the Royal Society for his work on barnacles in 1853, he was congratulated by Huxley, who had not only won the same medal two years earlier but was already serving on the society’s leadership council.

Darwin worked slowly due to delicate health—heart palpitations and stomach pain, often brought on by the slightest stress—but also because he could afford to do so. His father was a wealthy financier, his mother an heiress of the Wedgwood pottery empire. Huxley’s more accelerated ambition arose from necessity. He was born the second of eight children in West London, to a family so crimped by poverty they could not afford to educate him past the age of ten. Apprenticed to a series of semi-quack doctors from the age of thirteen, Huxley scraped his way into a barely reputable anatomy school, then Charing Cross Hospital, then the University of London, where he won academic medals in anatomy and physiology. Clearly brilliant but still lacking funds, he dropped out to join the Royal Navy as a surgeon’s mate at the age of twenty. Unlike Darwin, who spent his five years aboard the Beagle leisurely compiling notes, Huxley published numerous scientific papers while still aboard the Rattlesnake. Promptly elected to the Royal Society after landing back in England in 1850, he was appointed professor of natural history at London’s Royal School of Mines in 1854, a position he would hold for the next thirty-one years. Firmly established as a central figure in British science, he regularly encouraged his slow-paced, deliberative colleague. “Darwin might be anything if he had good health,” Huxley wrote, maintaining a keen, if slightly impatient, interest in what he knew of Darwin’s work in progress.

Darwin vividly recalled the exact moment of his revelation, in January of 1844. “I can remember the very spot in the road, whilst in my carriage, when to my joy the solution occurred to me.” He’d been a firm believer in the fixity of species, but as he excitedly wrote soon after,

I am almost convinced (quite contrary to opinion I started with) that species are not (it is like confessing a murder) immutable…. I think I have found out (here’s presumption!) the simple way by which species become exquisitely adapted to various ends.

Darwin’s concept, which he later labeled natural selection, differed from Lamarck’s in that he posited a different engine of species change. Rather than the direct result of adaptation, of adjusting to a new environment, Darwin believed evolutionary changes could be randomly introduced—glitches in reproduction’s internal matrix. While some changes might be detrimental, others could serve adaptive purposes, making an individual more likely to thrive (and reproduce) in its environment.

This struck him as more likely than Lamarckian evolution, which he described as “absurd though clever.” Yet in the fifteen years he would take to further refine the concept, he never thought of it as a refutation of Lamarck—it was entirely possible for both processes to coexist. Those fifteen years of development might have extended to a lifetime, had he not learned of the naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace’s work along parallel lines. “Wallace’s impetus seems to have set Darwin going in earnest, and I am rejoiced to hear we shall learn his views in full, at last,” Huxley wrote in 1858. “I look forward to a great revolution being effected.”

Rushed into print, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life was published on November 24, 1859. Darwin, nervously awaiting its reception, said, “If I can convert Huxley I shall be content.” The work’s first chapter is practically an homage to Lamarck:

Habit also has a decided influence…. The great and inherited development of the udders in cows and goats in countries where they are habitually milked, in comparison with the state of these organs in other countries, is another instance of the effect of use. Not a single domestic animal can be named which has not in some country drooping ears; and the view suggested by some authors, that the drooping is due to the disuse of the muscles of the ear, from the animals not being much alarmed by danger, seems probable.

The concept of “great and inherited development” was Lamarckian at its core. In Origin, Darwin made no attempts to dispute the validity of Lamarckian transformism, only to provide a parallel mechanism. In only one passage did Darwin postulate that natural selection could accomplish what transformism could not: in the case of “neuter insects” such as worker ants, which cannot mate. If they couldn’t reproduce, how could their traits be passed on?

“For no amount of exercise, or habit, or volition, in the utterly sterile members of a community could possibly have affected the structure or instincts of the fertile members, which alone leave descendants,” he wrote. “I am surprised that no one has advanced this demonstrative case of neuter insects, against the well-known doctrine of Lamarck.”

This did not disprove Lamarck’s work but augmented it. Indeed, Darwin’s theories had so little quarrel with Lamarck that in 1863, the Scottish geologist Charles Lyell described them as “a modification of Lamarck’s doctrine of development and progression.”

But Lamarck was dead. The only living target for the growing outrage over theories of evolution was Darwin, and he was disinclined to defend himself. As the controversy mounted he withdrew even further into his work, leaving Huxley (who would earn the nickname “Darwin’s bulldog”) to defend his ideas in public. In a famous debate at Oxford that took place seven months after the publication, Bishop Samuel Wilberforce asked Huxley: Did he trace his descent from a monkey through his grandfather, or grandmother? Huxley replied he would be prouder of having a monkey for an ancestor than someone who, like Wilberforce, used rhetorical skills to ridiculous ends.

While Huxley was happy to rise to a spirited defense of Darwin in public, in private he admitted to not exactly believing in Darwinian evolution, or Lamarckian transformism for that matter. He considered evolution “likely” (and Darwin’s theory more likely than Lamarck’s), but that was as far as he could take it. In both religious and scientific matters Huxley was an agnostic, a term he’d coined himself: It means “one who does not know” in Greek. His worldview was limited only to facts that could be confirmed, not ideas and dogma that required a leap of faith. Evolution, if it existed, appeared to operate on a timescale longer than a human lifespan. While future generations might be able to confirm it, they might also be able to disprove it. Until then, Huxley considered both theories of evolution only theories.

Darwin continued to rely upon Huxley as his research turned to the logical question implied by On the Origin of Species: If evolution is the gradual change of physical characteristics over time, by what means were physical characteristics transmitted? By 1865 he’d written up a working theory he called pangenesis, which he submitted to Huxley for review.

Huxley responded with puzzlement. Didn’t Darwin realize he was borrowing, practically to the point of plagiarism, from Buffon’s theory of the moule intérieur, the internal shaping matrix? It turned out that while Darwin was thoroughly familiar with Lamarck, he knew nothing at all of Buffon. While vaguely aware of the name, he had never read the man.

This startled Huxley. During his years as a naturalist in the navy, his crewmates had called his specimens “Buffons,” as the author’s name was prominent on the copies of Histoire Naturelle he carried with him. “I thank you most sincerely for having so carefully considered my manuscript,” Darwin replied. “It would have annoyed me extremely to have republished Buffon’s views, which I did not know of but I will get the book.”

Darwin found a copy of Histoire Naturelle and responded soon after.

“My dear Huxley,” he wrote, “I have read Buffon—whole pages are laughably like mine. It is surprising how candid it makes one to see one’s view in another man’s words. I am rather ashamed of the whole affair…. What a kindness you have done me with your vulpine sharpness.”

In the fourth edition of On the Origin of Species, published the following year, Darwin added an addendum entitled “An Historical Sketch of the Progress of Opinion on the Origin of Species.” In it, he admitted that Buffon “was the first author who, in modern times, has treated [the origin of species] in a scientific spirit. But as his opinions fluctuated greatly at different periods, and as he does not enter on the causes or means of the transformation of species, I need not here enter on details.”

He also acknowledged that “Lamarck was the first man whose conclusions excited much attention…. He upholds the doctrine that species, including man, are descended from other species. He first did the eminent service of arousing attention to the probability of all change in the organic, as well as in the inorganic world, being the result of law, and not of miraculous interposition.”

Yet Darwin was now taking pains to distance himself from Lamarck. “With respect to the means of modification, he attributed something to the direct action of the physical conditions of life, something to the crossing of already existing forms, and much to use and disuse, that is, to the effects of habit. To this latter agency he seemed to attribute all the beautiful adaptations in nature, such as the long neck of the giraffe for browsing on the branches of trees.”

Poor Lamarck and his giraffes. Here’s a popular English translation of what Lamarck had to say about giraffes:

This animal…is known to live in the interior of Africa in places where the soil is nearly always arid and barren, so that it is obliged to browse on the leaves of trees and to make constant efforts to reach them. From this habit long maintained in all its race, it has resulted that the animal’s fore-legs have become longer than its hind legs, and that its neck is lengthened to such a degree that the giraffe, without standing up on its hind legs, attains a height of six metres [nearly twenty feet].

The key factor here was the phrase “From this habit long maintained,” which in the original French reads Il est résulté de cette habitude, soutenue, depuis long-temps. While the word habitude can mean a simple act of repetition, it can also connote characteristic behavior. There is nothing here that conflicts with Darwin’s theory of natural selection: In a species that feeds on trees, individuals with a habitude of consuming a broad range of foliage could very well tend to live longer than those with a more limited diet, thereby having greater opportunities to reproduce.

In fact, the giraffe is an excellent example of sexual selection. Male giraffes use their necks and heads aggressively against each other to establish dominance, not unlike the agonistic displays of bucks and rams. Those hardened tufts on the top of the head (not horns but cartilage extrusions called ossicones) can kill another giraffe, especially when swung with the whiplike force of a longer neck. The mating successes of victors have reinforced a tendency toward thicker skulls, denser ossicones, and stronger neck musculature, the latter of which can support necks of greater length. They are embodiments of that popular, if not entirely accurate, summation of Darwinian thought: survival of the fittest.

On the Origin of Species became one of the most controversial books of its century. While many of its critics rejected evolution entirely on religious grounds, others found Lamarckian inheritance at least somewhat more theologically acceptable than Darwinian natural selection. A species’s ability to change through striving might be read as a gift from a beneficent Creator, and at any rate it seemed preferable to Darwin’s vision of cold, random chance. As the furor surrounding the book grew, the nuance that evolution might encompass two separate processes was lost in a sea of invective. In rushing to defend Darwin, some scientists felt compelled to attack Lamarck.

Taking their cue from Darwin’s own half-hearted acknowledgment of Lamarck, Darwinists seized upon (and mocked) the image of a prehistoric short-necked giraffe, straining to reach tree branches until his neck miraculously grew. It was absurd, but equally absurd was suggesting Lamarck had meant anything remotely like it in the first place. The irony was that the most widespread argument against Darwin rested on a similarly absurd oversimplification, namely that he believed humanity descended from monkeys, and unless he could produce a “missing link”—shades of the Great Chain—between humans and apes, his theory must be wrong.

Reports of experiments that “disproved” Lamarckian evolution also reflected this misconception. The German biologist August Weismann began cutting the tails off of a population of hundreds of mice, repeating the amputation across twenty-two generations. Well into the twentieth century, biology textbooks recorded that “Lamarck’s hypothesis would predict that eventually mice would be born with shorter tails or no tails at all. However, Weismann’s mice continued to produce baby mice with normal tails. Weismann concluded that changes in the body during an individual’s lifetime do not affect the reproductive cells or the offspring.” Another textbook displayed a picture of a dog and a puppy, with this caption:

Acquired characteristics are not inherited as Lamarck thought. Even though this adult Doberman has had its tail and ears cropped, you can see that its offspring still was born with long ears and tail.

Meanwhile Huxley, despite his reputation as “Darwin’s bulldog,” remained not a Darwinist but a complexist, holding that both theories had merit and deserved to be understood in a proper historical context. “I am not likely to take a low view of Darwin’s position in the history of science,” he wrote in 1882, the year of Darwin’s death, “but I am disposed to think that Buffon and Lamarck would run him hard in both genius and fertility. In breadth of view and in extent of knowledge these two men were giants, though we are apt to forget their services.”

But Huxley was a rarity. By then, Lamarck’s work was mostly seen as a regrettable misstep in the development of biology (a discipline, as noted, that Lamarck had named). Buffon was moved to the margins as well. Despite privately calling his ideas “laughably like my own,” Darwin’s public acknowledgment of Buffon had carried an equivocation (“but as his opinions fluctuated greatly at different periods…”) that stopped Darwin short of claiming him as a predecessor. This, along with Buffon’s known antagonism toward Linnaeus, helped give rise to what the British writer Samuel Butler called “the common misconception of Buffon, namely, that he was more or less of an elegant trifler with science, who cared rather about the language in which his ideas were clothed than the ideas themselves, and that he did not hold the same opinions for long together.”

Butler was a novelist, best known for the utopian satire Erewhon. But in 1879 he’d paused his career in fiction to write Evolution, Old and New, a book-length attempt to correct that misconception. Lost to contemporary audiences, he maintained, was the fact that Buffon’s seeming contradictions were rhetorical safeguards, pro forma verbal performances inserted to appease the Sorbonne and other censors of the day.

Buffon “sailed as near the wind as was desirable,” Butler explained, citing a passage from Histoire Naturelle that expressed one of Buffon’s more controversial ideas: that animals are not only intelligent, but in some important regards display an intelligence greater than ours. “Why do we find in the hole of the field-mouse enough acorns to keep him until the following summer?” Buffon had written. “Why do we find such an abundant store of honey and wax within the beehive? Why do ants store food? Why should birds make nests if they do not know that they will have need of them?”

Granting…that animals have a presentiment, a forethought, and even a certainty concerning coming events, does it therefore follow that this should spring from intelligence? If so, theirs is assuredly much greater than our own. For our foreknowledge amounts to conjecture only; the vaunted light of our reason doth but suffice to show us a little probability; whereas the forethought of animals is unerring, and must spring from some principle far higher than any we know through our own experience.

Asserting intelligence in animals was, Buffon knew, highly controversial: He’d already been censured for implying they had souls. To buffer the shock value of the paragraph, he followed immediately with

Does not such a consequence, I ask, prove repugnant alike to religion and common sense?

“This is Buffon’s way,” Butler pointed out. “Whenever he has shown us clearly what we ought to think, he stops short suddenly on religious grounds.” Buffon had, of course, done the same thing with species change, stating it boldly (to draw through time all other organized forms from one primordial type), then disavowing it in the very next paragraph (But no! It is certain from revelation). Histoire Naturelle is rife with such safeguards, necessities of their time but extraneous, if not confusing, to later readers.

Coming as it did from the pen of a novelist specializing in satire, Evolution, Old and New did little to rehabilitate Buffon’s reputation. But Histoire Naturelle’s author was not fading into obscurity. Far from it: While no longer taken seriously as a natural historian, Buffon remained a figure in the public imagination. He still served as a convenient foil for those burnishing Linnaeus’s life history, depicted as an unenlightened antagonist whose opposition to God’s Registrar arose not from disagreement but base motives. Why had he disputed Linnaeus? Opinions varied. The same Linnaeus biographer who attributed it to sheer ignorance (“did not understand the Linnaean system, nor chose to give himself any trouble to understand it”) added that “this great man in the violence of his attacks and criticisms, was chiefly hurried away by jealousy.” Another, more generous-minded writer explained Buffon’s “inaccuracy and thoughtlessness in his manner of judging Linné” by attributing it to a grandiose character: “It would seem that, cut out by nature on a large scale, it was difficult for him to stoop to the contemplation of little things.” Nevertheless, he concluded, the man had widely missed the mark. Buffon’s notions of nature “cannot be that of our days.”

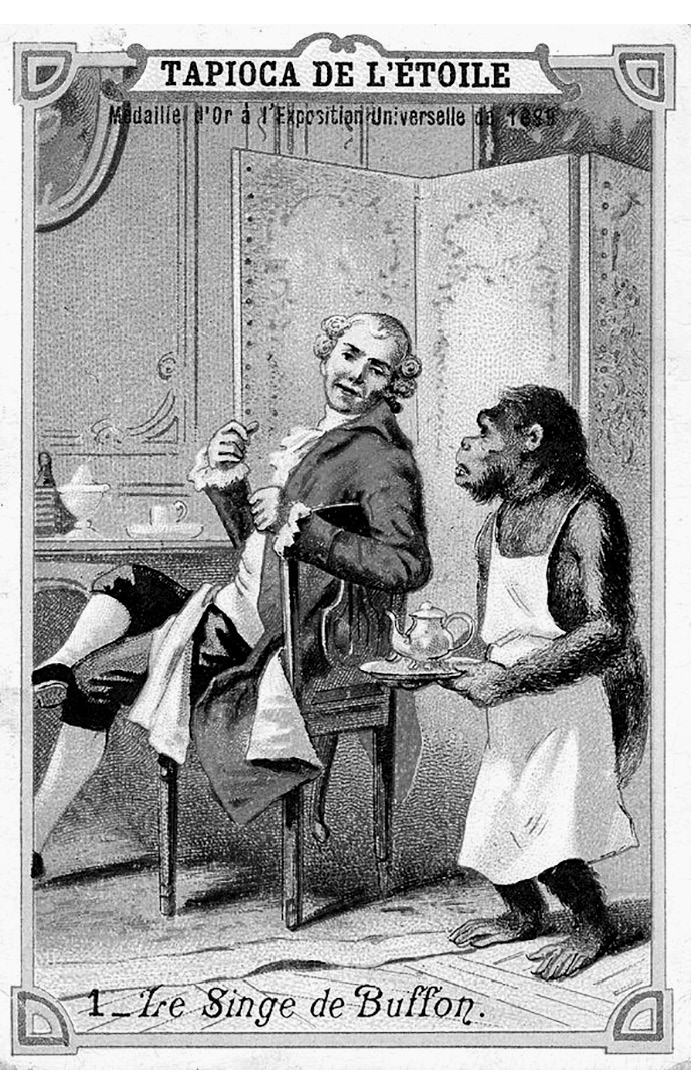

Other scholarship was less than stellar. In his book Anthropoid Apes, the German naturalist Robert Hartmann acknowledged Buffon chiefly as an animal trainer, publishing as fact a fanciful account of an ape in the Montbard menagerie. “Buffon’s chimpanzee…sat down to table like a man, opened his napkin and wiped his lips with it, made use of his spoon and fork, poured out wine and clinked glasses, fetched a cup and saucer and put in sugar, poured out tea, let it get cold before drinking it,” he wrote. “He took such a fancy to one lady, that when other people approached her he seized a stick and began to flourish it about, until Buffon intimated his displeasure at such behaviour.”

Buffon and simian servant, advertising tapioca

It is telling that Hartmann, a distinguished anatomy professor at the University of Berlin, did not bother consulting the source. Buffon had only briefly mentioned (in volume fourteen of Histoire Naturelle) that he had once seen an orangutan on display in Paris, a sickly specimen with a heavy cough and a fondness for sweets. This heavily embroidered version caught on in the public imagination, dovetailing as it did with the predominant image of Buffon as a quaint-at-best eccentric. A French confection manufacturer began featuring Buffon in its advertisements, depicting him as pleased to be waited upon by a comically domesticated companion.

Yet Buffon remained a bestselling author, after a fashion. He was deprived of a direct heir after Buffonet’s death by guillotine in 1794, and the Buffon fortune had largely drained into revolutionary coffers. The remnants of the estate were only belatedly claimed, by distant relations. Buffon’s great nephew, Henri Naudault de Buffon, honored his memory by publishing selected correspondence (from the few papers that had survived Buffon’s habit of burning), but neither he nor other descendants made any claims on the copyright of Histoire Naturelle itself. This made the massive text and its painstakingly compiled illustrations fair game for reprinting and repurposing. It became common to use Buffon’s original work as the basis for a jumble of verbiage on nature, appropriating his name for marketing purposes. Take, for instance, the “edition” of Buffon’s Natural History of Man, the Globe, and of Quadrupeds, published in 1857 in New York by Leavitt & Allen. Its preface promised “facts calculated to excite astonishment, and perhaps a higher feeling, and to yield innocent entertainment, or valuable information.”

The materials for these volumes have been drawn from celebrated naturalists; from Buffon, the most eloquent of them all, from Cuvier, Lacépède, and many others, whom it would be superfluous to enumerate. Various interesting particulars have also been gleaned from the narratives of modern voyagers and travellers.

While Buffon had passed his life’s work on to Lacépède, he would have been surprised by who was also sharing the pages of Histoire Naturelle. The 1857 version included his surveys of human diversity and cautions against racial categories (“the dissimilarities are merely external, the alterations of nature but superficial”), but the editors tacked on a disclaimer: Such is Buffon’s arrangement of the varieties of the human race. Other naturalists, however, differ widely from him, and the systems which they have formed are numerous. According to Linnaeus…

What follows is a direct quotation of Systema Naturae’s four racial categories, then a more recent definition of “the white race” as “characterized by regularity of form, according to the ideas which we have of beauty.” Rounding out the chapter is an account of conjoined twins, “now exhibiting in the British metropolis.”

For several decades, such versions sold briskly. But the conversion of Histoire Naturelle into a hodgepodge of sources was an attempt to maintain its relevance, and that could not be indefinitely sustained. Eventually publishers turned from adulteration to simplification, producing increasingly abridged editions that emphasized the illustrations and streamlined the language. Because of this, in the realm of public imagination Buffon increasingly became a de facto popularizer, if not a writer of texts for the young. One unauthorized edition, entitled Buffon for Little Children, with Pictures, boiled a few dozen entries into a primer for beginning readers. (“The squirrel has gentle manners, although it sometimes grasps small birds nearby.”) As George Bernard Shaw recalled,

One day early in the eighteen hundred and sixties, I, being then a small boy, was with my nurse, buying something in the shop of a petty newsagent, bookseller, and stationer in Camden Street, Dublin, when there entered an elderly man, weighty and solemn, who advanced to the counter, and said pompously, “Have you the works of the celebrated Buffoon?”

The incident struck him as funny, as even small children knew “the celebrated Buffoon was not a humorist, but the famous naturalist Buffon. Every literate child at that time knew Buffon’s Natural History as well as Aesop’s Fables. And no living child had heard the name that has since obliterated Buffon’s in the popular consciousness: the name of Darwin.

“Ten years elapsed,” Shaw continued. “The celebrated Buffoon was forgotten.”