Sex with humanlike artifacts is by no means a twenty-first-century concept—in fact, its foundations lie in the myths of ancient Greece. A Cypriot sculptor, King Pygmalion I, made an ivory statue in the form of a woman that was so beautiful he fell in love with it, gave it a name—Galatea—and desired it. So he prayed to Aphrodite, the goddess of love, and one day while Pygmalion was kissing the statue, Aphrodite brought it to life. Pygmalion’s kisses were suddenly being reciprocated, and finally he married Galatea. The myth of Pygmalion thus led to the name tag “pygmalionism,” for the fetish of sexual attraction to statues.*

In his authoritative 1909 tome The Sexual Life of Our Time, Iwan Bloch explains one of the oldest of religiosexual phenomena, the act of “religious prostitution,” as a form of pygmalionism. This is an act of sacrifice, made to a deity, most often taking the form of a sacrifice by a woman of her virginity shortly before giving herself to her husband for the first time. The defloration process would sometimes be accomplished with a penis made of ivory, stone, wood, or even iron and sometimes by a form of pygmalionism—intercourse with a statue of the god. As an example of this practice, Bloch describes how a bride at a religious shrine near Goa would be assisted by her friends and relatives in mounting the stone penis of an image of a god, thereby destroying her hymen.

In this religiosexual act, the statue is a representation of a deity, but in the far more common form of pygmalionism the statue substitutes not for a deity but for a living human being. In the brothels of late-nineteenth-century Paris, it was not uncommon for prostitutes to act out a variation on this theme, standing on suitable pedestals as though they were statues and being watched by their clients as they gradually appeared to come to life. Such a scene induced sexual enjoyment in the Parisian pygmalionists, often elderly patrons who no longer had the energy for sex. At about the same time, the French talent for inventing mechanical automata such as Vaucanson’s duck and Maillard’s swan,* when combined with the legendary French expertise in matters sexual, led to the invention of artificial devices, and even whole artificial bodies, designed to provide substitutes for human genitalia.

Bloch describes how these were employed, to act as surrogate sex partners.1

AN ARTIFICIAL VAGINA

…we may refer to fornicatory acts effected with artificial imitations of the human body, or of individual parts of that body. There exist true Vaucansons in this province of pornographic technology, clever mechanics who, from rubber and other plastic materials, prepare entire male or female bodies, which, as hommes or dames de voyage, subserve fornicatory purposes. More especially are the genital organs represented in a manner true to nature. Even the secretion of Bartholin’s glands* is imitated, by means of a “pneumatic tube” filled with oil. Similarly, by means of fluid and suitable apparatus, the ejaculation of the semen is imitated. Such artificial human beings are actually offered for sale in the catalogue of certain manufacturers of “Parisian rubber articles.” A more precise account of these “fornicatory dolls” is given by René Schwaeblé (“Les Détraqués de Paris,” pages 247–53).

From René Schwaeblé’s description of these fornicatory dolls, sold by a “Dr. P” for around three thousand francs, it would appear that they were extremely convincing replicas of the female form.† The doctor explained to Schwaeblé:

Every one of them takes at least three months of my work! There’s the inner framework which is carefully articulated, there’s the hair on the head, the body hair, the teeth, the nails! There’s the skin, which has to be given a certain tint, certain contours, a particular pattern of veins. There are the eyes, which need to be given some expression, there’s the tongue, and I don’t know what else. You won’t find a waxwork or a statue, not even the ones created by the greatest masters, that can be compared to my products. The only thing these haven’t got is the power of speech!…

Unfortunately I can’t advertise openly. The police keep interfering in my business, and I have to keep some weird rubber animals around the place, so that I can say I’m a maker of inflatable figures for funfairs!

Doctor P occasionally had customers who wanted a doll made in the likeness of someone they desired.

It quite often happens that one of those “mad women” falls for a man in the public eye—a politician, a jockey, some hammy actor, or whatever. As she doesn’t dare to become his mistress, or can’t, she applies to me and asks me to create a doll modelled on her idol.

…

Madame X——lost her husband last year. Two days after his death, she came to me and asked me to craft a doll in the image of the deceased. Didn’t she get on my nerves! Every afternoon she would settle herself in my studio and watch me at work, showering me with advice: “Skin more pink here! More hair there! Lip curling up a little! A more cheerful eye!” When the doll was finished she took it home with her. Since then she’s been living with it, she never leaves it. She dresses it in her husband’s own clothes, puts it to bed beside her at night, kisses it, caresses it and tells it all sorts of naughty things!2

With real products available for purchase in fin de siècle France, such as the one described here by Schwaeblé, it is hardly surprising that French fiction of that time made use of fornicatory dolls. Bloch wrote:

The most astonishing thing in this department is an erotic romance La Femme Endormie, by Madame B.; Paris, 1899, the love heroine of which is such an artificial doll, which, as the author in the introduction tells us, can be employed for all possible sexual artificialities, without, like a living woman, resisting them in any way. The book is an incredibly intricate and detailed exposition of this idea.3

So “shocking” was the content of La Femme Endormie that not only did the author feel the need for anonymity, but the book boldly displayed the misinformation that it was printed in Melbourne, in an attempt to throw off any straitlaced French authorities who might be seeking to take legal action against the printer or to prevent further copies from being distributed.

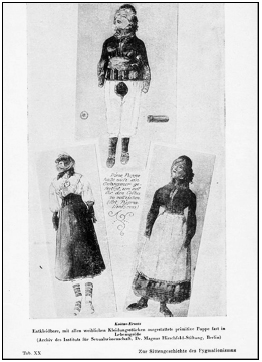

FORNICATORY DOLLS

Is it a far cry from titillating nineteenth-century French fiction to mid-twenty-first-century sexual robots? Part two of this book aims to convince any skeptics among you that this transition will indeed materialize.