Mike Kolendorski had a dramatic announcement for his family: he was going to England to join the Royal Air Force. It was a decision he had made by himself, without consulting any of his relatives. The reaction he received was predictable, considering the mood of Americans toward England in the spring of 1940.

His family told Mike that he was crazy—the war was England's worry, not his. As an American, he had no quarrel with the Germans. And as a Californian, he did not owe the British one damn thing. California was not at war with Germany and had never, not even in 1776, been a British colony. He would be much better off, he was told, if he stayed home and got a good job.

Besides, it looked as though the British had already lost the war. The British Army had just been chased out of France—what was left of it had been evacuated from Dunkirk, wherever the hell that was—and it looked like Hitler was going to invade England any day. Before the summer was over, the German army would probably be in London.

This was a popular point of view among Americans in the spring and summer of 1940, when Britain faced Germany and its vaunted Luftwaffe all alone. Even the American ambassador in London, Joseph P. Kennedy (father of future president John F. Kennedy), was telling anyone who would listen that the British were not only losing the war, but that they had no chance of winning it.

Many American reporters in Britain shared Kennedy's opinion that “chances now seem[ed] less than even that the British Isles [could] hold out” for six months “against intensive bombing followed by an attempted invasion.”1 It was hard to understand why anybody would want to volunteer to join the air force of a country that was going to lose. Besides, the war was none of America's business.

The reasons for wanting to join the Royal Air Force were hard to express, even for a young Polish-American who knew all the answers. Hardly any of the American volunteers, in the RAF or any other branches of the British armed services, could explain their motives very clearly. This was partly because they were young and inarticulate, partly because their reasons were difficult to put into words, and partly because they did not really know the reasons themselves.

Mike Kolendorski did have concrete reasons for wanting to leave home and join the RAF. He and his family still had close ties with Poland, and they spoke Polish at home. Going into the British air force was the best way he knew to fight the enemy who had overrun his family's homeland. He had very strong feelings about this—so strong, in fact, that they would prove to be his undoing.

But most did not have such clear-cut motives. Some joined out of idealism; they had read Ernest Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls and wanted to fight the Nazis like Hemingway's hero fought the Fascists in Spain. Others had the feeling that the United States would be in the war sooner or later and that their experiences in the RAF might prove useful later on in the US forces. Some were just restless and looking for a bit of excitement; one volunteer said that it was like running away to join the circus.

One American who volunteered to join the Royal Air Force, James A. Goodson, was just mad as hell at the Germans. He had been aboard the British ocean liner Athenia when it was torpedoed by a U-boat on the day that war was declared in September 1939. The idea of joining up occurred to him when he landed in Scotland with some other survivors. In Glasgow he happened to pass a recruiting station and asked one of the men on duty, “Can I join your RAF?” (He actually did not join until he recrossed the Atlantic and made his way to Canada to join the RCAF—Royal Canadian Air Force.)2

American author Mary Lee Settle volunteered for the Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) of the RAF. She is not exactly sure why she joined. She puts it down to being romantic.

Another volunteer who went through Canada to join the RAF explained that he was twenty years old at the time, not going anywhere in particular, and brainless. He had heard that the British were looking for pilots to fight the Germans. Because he was young and stupid and interested in airplanes, he thought he might as well give it a try and join the RAF. In other words, it was a form of temporary insanity.

As an afterthought, he mentioned that all of his relatives tended to agree with him. They thought he was a goddamn screwball; it was bad enough to be drafted into the American army, but to volunteer—and with the British air force, at that—was something they just could not get over.

The idea to recruit American pilots for foreign forces first occurred to Colonel Charles Sweeny, a wealthy American businessman with family connections in London. His original intention was to send his recruits to France and l’Armée de l’Air, the French air force. This plan was modeled on the precedent of the Lafayette Escadrille, a group of Americans who volunteered to fly for France in the First World War.

Thirty-two of Sweeny's l’Armée de l’Air volunteers reached France in early 1940. But when France surrendered in June of that year, the Americans found themselves trapped by the advancing German forces. Four of them were killed; nine others were taken prisoner. Six of the group managed to escape to England, and five of these found their way into the Royal Air Force.

The young volunteers may have been vague about their reasons for joining, and sometimes did not seem to have any reason at all, but Britain's Royal Air Force had one solid reason for accepting the Americans—they were desperate for pilots.

Pilots of 601 (County of London) Squadron sprint toward their Hurricanes sometime during the summer of 1940. Number 601 was called the “millionaire's squadron.” It was made up mainly of wealthy young men of social standing, including Chicago-born Billy Fiske. (Courtesy of the National Museum of the United States Air Force®.)

After the British army had been evacuated from Dunkirk in June 1940, the Luftwaffe began operating from airfields in northern France. With the Germans just across the channel from the beaches of southern England, the British Air Ministry had a dire need for trained pilots. Prime Minister Winston Churchill had already referred to the upcoming air battle as the “Battle of Britain.” It was certain that RAF Fighter Command would be needing as many trained pilots as it could get.

American volunteers were not the only source for pilots—Fighter Command was scouring flyers from everyplace available. The Royal Navy transferred seventy-five of its pilots to the RAF, many of whom were only partially—and very hurriedly—trained to fly fighter planes. A few army pilots who flew unarmed reconnaissance planes were also pressed into service as fighter pilots.

Even more welcome were the combat-seasoned pilots from countries that were now occupied by the Germans: Belgians, French, Czechs, and Poles. There were very few of them, however—only twelve French pilots managed to escape to England, and just twenty-nine Belgians got away—and these pilots also had their drawbacks. Many were not used to advanced fighters like the Spitfire and the Hurricane. Most had flown planes with fixed landing gear. After giving an expert display of loops, rolls, and dives, they would sometimes wreck their planes when they forgot to put their wheels down before landing.

Language was another problem. The Polish pilots, for instance, were among the best and most determined in RAF Fighter Command, but they did not speak a word of English. They would address their squadron leader as mon commandant and the flight lieutenant as mon capitaine. They would have to learn the rudiments of Standard English, at least, before they could become operational. They would also have to learn basic flight jargon, such as “angels,” “vector,” “bogie,” and “bandit.” Without the ability to communicate with ground controllers, the Poles would be as good as useless, for all their experience and determination.

In an attempt to minimize the language barrier, Fighter Command asked permission to accept American volunteers. The Yanks might not have the combat techniques of the Poles, the French, or the Czechs, but at least they spoke a language that was roughly similar to English. They could be vectored toward an incoming enemy bomber formation by ground control and usually could be understood when they spoke.

And so, with the approval of the Air Ministry, American citizens were recruited to join the RAF. Advertisements were even placed in American newspapers. This notice appeared in the New York Herald Tribune:

LONDON July 15 [1940]: The Royal Air Force is in the market for American flyers as well as American airplanes. Experienced airmen, preferably those with at least 250 flying hours, would be welcomed by the RAF.

The article went on to advise candidates that to join the RAF they would be required to travel to Canada at their own expense and would also have to pass the physical examination. “For such volunteers,” the notice went on, “there will be no question about signing or swearing an oath of allegiance to the British crown.”3

When George VI waived the oath of allegiance in June, it was an open admission of the historical prejudices between the two countries. The Air Ministry feared that the oath would frighten away any potential American volunteers, since no American would swear loyalty to the great-great-great-grandson of George III.

Occasionally, however, the oath did become a point of controversy. An RAF group captain, apparently not aware that the requirement had been waived, announced to eight incoming Americans that His Majesty would accept them as pilots as soon as they had sworn allegiance to him. It was a tense few minutes until the group captain was taken aside and corrected by another officer. Maybe it was because of what had been promised in the newspaper notice, or maybe it was because of George III and the Boston Tea Party and Bunker Hill—whatever it was, all eight of the American volunteers were ready to go home instead of taking the oath.

But the oath of allegiance was only one obstacle. A far greater problem was the three Neutrality Acts that had been passed by Congress in the 1930s.

The United States was a neutral country in the summer of 1940 and was determined to stay that way. One of the three Neutrality Acts made it a criminal offence to join the armed forces of a “belligerent nation”—including Britain. It was against the law for an American citizen to join the RAF. Anyone caught trying faced the prospect of stiff punishment: ten years in prison, a $20,000 fine, and loss of US citizenship.

Six potential volunteers found out about the Neutrality Acts the hard way. They had spoken with Colonel Sweeny and, in late 1940, headed for the Canadian border to join the RAF. Just before their train crossed the border and made its first stop inside Canada, the six young fellows were met by agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The FBI men gave them a choice: either go back home or go to prison. It was not a hard decision—the six went back home. But they did try again. On the second attempt they made it to Canada without any interference and, finally, over to England.4

When James A. Goodson joined the RCAF, he was warned that he would probably lose his US citizenship because of the US Neutrality Acts. He understood that all other US citizens received the same warning from the RCAF and RAF.5

The warning did not deter young Mr. Goodson. He also made the trip from the United States to Canada to England, where he flew Spitfires with 133 (Eagle) Squadron. Pilot Officer Goodson transferred to the US 4th Fighter Group in 1942, when the Eagle Squadrons (there were three of them by this time) were absorbed into the US Eighth Air Force. The Americans were very glad to receive such an experienced fighter pilot into their command. P/O Goodson was commissioned as a lieutenant (the equivalent US rank to P/O), and all warnings concerning loss of US citizenship were conveniently forgotten.6

The Neutrality Acts did not prevent other young Americans from joining the RAF, either. Colonel Sweeny was responsible for recruiting many of the volunteers. Some made their own way to England. They either went to Canada and joined the Royal Canadian Air Force, or they booked passage to England as “reporters” or under other false covers. A Wall Street banker told the customs official in Boston that he was going to Canada “for some shooting.”7

The official records of the Royal Air Force list only seven Americans as having served with RAF Fighter Command in the summer of 1940.8 But there were many, many more than this. Because it was against the law to join, any number of Americans would not divulge their true nationality when signing their enlistment papers. Nobody knows exactly how many pilots, “officially” listed as Canadians or as Commonwealth citizens, were actually American. Especially suspect are those with Anglo-Saxon names like Johnson, Little, or Mitchell. Air Ministry records list them as Canadian, which is no proof that they really were. Many of them were “American Canadians.”

One such American pilot in Fighter Command is mentioned by Pilot Officer Donald Stones of 79 Squadron. P/O Stones recalled a Flight Lieutenant Jimmy Davis, “an American who had been commissioned in the RAF before the war.” According to Stones, Jimmy Davis was shot down and killed on the same day that King George visited Biggin Hill, 79 Squadron's base, to award decorations. Davis was to have received the Distinguished Flying Cross on that occasion. The king asked about the remaining DFC on the table and was told about the expatriate American. Stones thought the King was “quite moved.”9

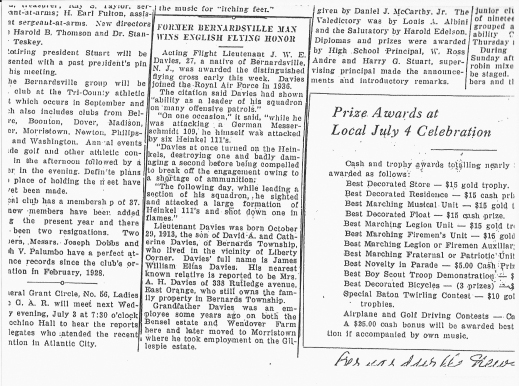

As it turned out, Stones had his names confused, although his facts were correct. The American pilot he remembered was named Davies, not Davis. (No one named Jimmy Davis is listed in any official records as belonging to any RAF fighter squadron during the Battle of Britain.) Jimmy Davies certainly was an American; he was born in Bernardsville, New Jersey, in 1913. He came to Britain in the early 1930s and was commissioned in the RAF in 1936. He is credited with shooting down one of the first German airplanes of the war—a Dornier Do 17 on November 21, 1939, which he shared with a British flight-sergeant named Brown.10

By the time Flight Lieutenant Davies was shot down and killed on June 25, 1940, he was officially credited with six enemy-aircraft destroyed. That would make him the first American “ace” of the Second World War.

This story about Jimmy Davies appeared in the Bernardsville News, Bernardsville, New Jersey's local newspaper, on June 27, 1940. By the time readers in Bernardsville saw this article, Jimmy Davies was dead. He had been killed in combat on June 25, two weeks and one day before the Battle of Britain officially began. Jimmy Davies was already an ace, having destroyed six enemy aircraft by June 8 and had earned the Distinguished Flying Cross. (Reprinted with permission from the Bernardsville News/the New Jersey Hills Media Group.)

Nobody really knows how many “secret Americans” served in the Royal Air Force in the summer of 1940, or how many Canadians were actually “American Canadians,” and there are few clues. The only traces that remain of their true nationality are nicknames, buried in the war records—“Tex,” or “America,” or “Uncle Sam.”

One American who made no secret of his citizenship was Billy Fiske. Chicago-born, William Mead Lindsley Fiske III was the son of an international banker and attended Cambridge University. After leaving Cambridge, he enjoyed a life of wealth and leisure, became a champion toboggan sledder, and entered society when he married the former wife of the Earl of Warwick. Fiske settled in England, where he did weekend flying during the 1930s. With his influential friends and family connections, he had no trouble at all getting into the RAF Auxiliary in 1940.

In July, Pilot Officer Fiske was posted to 601 Squadron. Auxiliary squadrons, including 601, were made up mainly of wealthy young men of social standing. In prewar days, pilots were selected for the Auxiliaries because of their school, their club, and their social connections rather than for their talent for flying. These units have been referred to as associations of snobbery and class prejudice.

Number 601, nicknamed “the millionaire's squadron,” was no exception. “They wore red linings in their tunics and mink linings in their overcoats,” according to Mrs. Fiske. “They were arrogant and looked terrific, and probably the other squadrons hated their guts.”11

Billy Fiske was highly thought of by the other members of his squadron. His commander, F/Lt. Archibald Hope called Fiske “the best pilot I've ever known…natural as a fighter pilot. He was also terribly nice and extraordinarily modest. He fitted into the squadron very well.”12

During the Battle of Britain, 601 Squadron was based at Tangmere. The Tangmere wing was responsible for the defense of southern England against the German bomber fleets. In July and August, the Germans did their best to destroy Fighter Command and its airfields in preparation for the pending invasion of England. Operational fighter squadrons, including 601, saw combat nearly every day.

On August 13, during one of his first operational sorties, Pilot Officer Fiske shot down a Junkers Ju 88 twin-engine bomber. Three days later, while Tangmere was under attack, Fiske's Hurricane was jumped while he was returning to base. Fisk crash-landed his shot-up fighter on the aerodrome's grass landing field.

An ambulance crew lifted Fiske out of the Hurricane's cockpit. Flight Lieutenant Hope saw him lying on the grass next to the fighter plane; Fiske was burned on the face and hands, but did not seem seriously injured. Hope told Fiske that he would be all right, since he seemed to be suffering from only a few minor burns.

When the squadron adjutant visited Fiske in hospital that night, what he saw seemed to confirm Hope's optimism: “Billy was sitting up in bed, perky as hell.” But, Hope recalls, “The next thing we heard, he was dead. Died of shock.”13 He died on August 17, the day after he had been shot down.

Pilot Officer Fiske's obituary in the Times (London) of August 19 ran for thirty-nine lines—unusually long for such a junior officer. The standard obituary for officers ran seven or eight lines; senior officers sometimes received fifteen or twenty lines of print. Fiske was given so much space partly because he was married to the former Countess of Warwick and partly because he was an American—a major concern of the British press was to show Americans that their fellow countrymen were already in the war. It was part of a subtle—and sometimes not so subtle—propaganda campaign to arouse American sympathy and enlist American support for Britain.

Billy Fiske is usually described as “the first American serving as an officer in the RAF to lose his life in action against the enemy in this war.”14 He was certainly the first “official” American to be killed, but it is likely that some of the US citizens listed as Canadians lost their lives even earlier. Jimmy Davies of 79 Squadron, for instance, was killed on June 25, nearly two months before Billy Fiske.

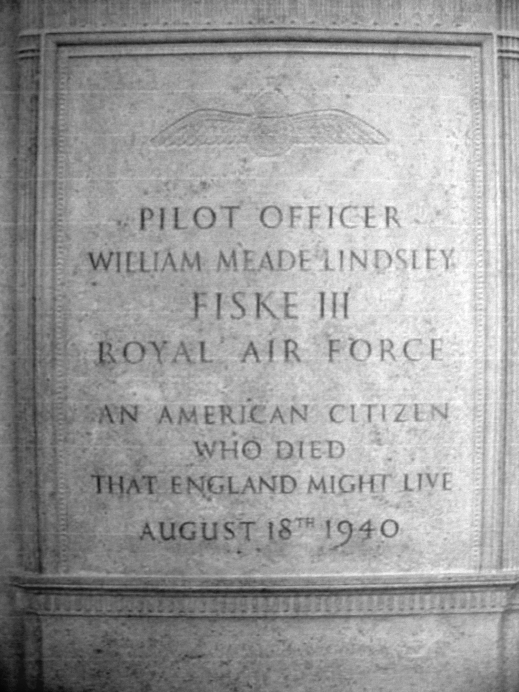

Fiske is buried in the churchyard of Boxgrove Priory Church in West Sussex, not far from Tangmere. He is also commemorated by a memorial plaque in the crypt of St. Paul's Cathedral in London—which cynics cited as yet another propaganda attempt to sway neutral Americans to Britain's side. The plaque is dedicated to WML Fiske: “An American citizen who died that England might live.”

Pilot Officer Billy Fiske's memorial plaque in St. Paul's Cathedral. Cynics said that the plaque was an attempt to sway neutral America to Britain's side. (Photo by the author.)

A somewhat more everyday American—he described himself as “a farm boy” from St. Charles, Minnesota—was Arthur Donahue. Donahue went to Canada to join the RAF after Dunkirk. He arrived in England on August 4, 1940, and was assigned to 64 Squadron, which flew Spitfires out of Kenley Aerodrome, south of London.15

On his first sortie, Donahue damaged a Messerschmitt Bf 109—after first making sure that it was not really a Spitfire or a Hurricane—and had his own Spitfire damaged by a German cannon shell. The 20 mm shell severed several control cables and blew out the battery connection that operated his gunsight. When he brought his Spitfire back to Kenley, it needed a new fuselage.

On August 8, Donahue's flight was on patrol over the Channel when the six Spitfires were jumped by a “gruppe” of about twenty-seven Messerschmitts. In the resulting free-for-all, Donahue (nicknamed “America” by his squadron mates) shot at several Bf 109s, “just firing whenever I saw something with black crosses in front of me.” He locked onto the tail of one, fired a good burst into it, and was credited with a “probable” when he returned to base.16

Four days later, he attacked a flight of three Bf 109s by himself and got shot down for his pains. Cannon shells proved his undoing for the second time, putting a hole in his Spitfire's fuel tank and setting the plane on fire. Donahue was able to bail out, but not before being severely burned by the exploding fuel tank. He came down in an oat field; fortunately, he landed close by a detachment of soldiers who were able to call an ambulance. Donahue spent the next seven weeks in hospital.

Three of the Americans signed by Charles Sweeny for l’Armée de l’Air managed to leave France on the very last ship for England. After France gave up the fight and signed an armistice with Germany on June 22, these three Yanks—Andy Mamedoff, Eugene Q. “Red” Tobin, and Vernon C. “Shorty” Keough—joined the RAF and wound up in 609 (West Riding) Squadron.17

Red Tobin and Andy Mamedoff originally had signed up as pilots in Finland's air force after Russian troops invaded Finland in November 1939. Neither one of them had any experience with fighter planes or military flying—Tobin claimed 200 hours in light civilian aircraft, and Mamedoff had done some barnstorming (flying demonstrations, often at county fairs). But the prospect of being fighter pilots sounded exciting, and the promised pay of $100 per month also helped to persuade them. The fact that Andy Mamedoff's family had been driven out of Russia by the Communists, the same people who had invaded Finland, was added incentive for him.

But the Russo-Finnish war ended in the winter of 1940, when Finland was forced to surrender. At that stage, Tobin and Mamedoff had not yet left California. They were still determined to be fighter pilots, though. Since the French air force looked as good to them as the Finnish, they signed up with l’Armée and set off for France.

Between California and France, they met up with four-foot-ten-inch Vernon “Shorty” Keough, from Brooklyn, New York. Shorty had been a parachute jumper in the 1930s, making hundreds of jumps at air shows and county fairs. He probably would have been the shortest pilot in the French air force, but the war did not last long enough for him to find out.

Although the Americans arrived before France surrendered, they did not get the chance to do any fighting. Which was probably just as well, considering the antiquated state of the French air force—l’Armée did not have any fighter that could hold its own with the Bf 109. France formally surrendered on June 22, the same day that Tobin, Keough, and Mamedoff reached the French port of Saint-Jean-de-Luz after managing to evade the advancing Wehrmacht. Two days later, they landed in England aboard the steamer Baron Nairn.

They went to the US embassy in London for assistance and were nearly deported. The embassy staff was not overjoyed to see three US citizens trying to enter the armed services of a foreign government and tried to have them sent back to the United States. Ambassador Joseph P. Kennedy was a staunch isolationist, if not outright anti-British. The three Americans had already violated the Neutrality Acts by joining the French air force. Kennedy was determined that they would not join the RAF.

But Tobin, Keough, and Mamedoff got around Ambassador Kennedy with the help of a sympathetic member of Parliament. The MP got them into the RAF, and the Air Ministry sent them off to a training school in Cheshire where they were taught to fly Spitfires. From the training units, the three were sent as replacements to 609 Squadron based at Warmwell in Dorset. Warmwell was one of Fighter Command's front-line bases against the Luftwaffe.

The three new Pilot Officers fit in very nicely with their new squadron and seemed to be well liked. None of the British flyers had ever seen a real, live Yank before. Now there were three of them, right in the officers’ mess.

Everyone seemed amused by their transatlantic squadron mates. Lanky Red Tobin, with his wisecracks and easygoing manner, was thought to be “typically American.” Because he was from California, which every movie-loving Brit knew was somewhere in the Wild West, Red was compared to a film cowboy—one pilot said that he might have stepped right out of a western.

Andy Mamedoff, stocky and mustachioed, was known for his overfondness of gambling—he would make a bet with anybody on just about anything. And Shorty Keough, at four-feet-ten-inches, was known for being short. A squadron mate said that Shorty was “the smallest man I ever saw, barring circus freaks.”18 Keough needed two cushions in the cockpit—one to sit on, the other for the small of his back. With the help of his pillows, he was able to fly a Spitfire, although “all you could see of him was the top of his head and a couple of eyes peering over the edge of the cockpit.”

During his career as a parachute jumper, Shorty had survived 486 jumps. Whenever anybody asked him why he was so short, he would reply that he used to be of normal height until he became a jumper—the impact of all those landings pushed his legs right up inside his body. You ask a stupid question, you get a stupid answer.

Soon after the Americans joined 609 Squadron, Warmwell was visited by Air Commodore Prince George, the Duke of Kent. The Yanks had only just arrived in the country and had never met a Duke before. “Say,” Shorty wanted to know, “what do we call this guy—Dook?” He was told that “sir” would do very nicely, which must have put his mind at ease. Shorty's stories about his varied and colorful career, told in fluent Brooklynese, kept the “Dook” spellbound.

The squadron seemed to accept the Yank replacements without any sign of condescension, which is surprising. Number 609 was an Auxiliary squadron. Auxiliary pilots usually regarded members of the Volunteer Reserve—and all three Americans were with the Volunteer Reserve—as being of inferior social rank, if not absolutely subhuman.

The standard Auxiliary joke about VR pilots was: “A regular RAF officer was an officer trying to be a gentleman; an Auxiliary was a gentleman trying to be an officer, and a Volunteer Reservist was neither, trying to be both.” There was no joke about American VRs. Or, at least, none were ever repeated outside the officers’ mess.

There was no snobbishness at all shown toward the three Yanks. “They were typical Americans,” said one of their fellow squadron members, “amusing, democratic, always ready with some devastating wisecrack—frequently at the expense of authority—and altogether excellent company. Our three Yanks became quite an outstanding feature of the Squadron.”19

According to the findings of an opinion poll that was taken during the war, the British tended to look upon the “typical American” with a detached familiarity, albeit with the recognition of a few certain defects of character, most of which stemmed from the Declaration of Independence in 1776. The men of 609 Squadron were even willing to overlook this last flaw.

Tobin, Keough, and Mamedoff were “affectionately…regarded as considerably larger than life,” and one RAF history referred to them as the “amazing trio.”20 In addition to a great deal of curiosity, some admiration, and maybe just a tinge of condescension, they were also regarded with a touch of awe. The awe was certainly misplaced, since it was based largely upon inflated flight histories—Red Tobin, for instance, increased his flying time from 200 hours to 5,000 hours.21

Great things were also expected from the three Yanks in gunnery. Each Spitfire had eight .303 machine guns, and from Hollywood cowboy and gangster films, everybody knew that Americans were “good with guns.” The squadron commander did not share this enthusiasm, however. Squadron Leader Horace “George” Darley was not about to let the three “new boys” go up against the Luftwaffe until he was satisfied that they could look after themselves. The Yanks might have been keen, courageous, and all that, but these qualities were no substitutes for solid training.

When they joined the squadron, Darley assigned the three Americans to noncombat duties. Mostly, they flew ferrying jobs—delivering a Spitfire to another base and being flown back in a twin-seat Miles Magister trainer—until they knew everything there was to know about Spitfires. Tobin, Keough, and Mamedoff were not wild about this arrangement. Nearly every day they heard the other pilots talking about their encounters with enemy bombers and fighters, while all they were allowed to do was run errands.

On August 16, the three of them were finally pronounced “operational.” This was the third day of Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring's Adlerangriff (Eagle Attack), the Luftwaffe's concerted effort to destroy the Royal Air Force, including its radar network and all of its communications facilities.

When the “scramble” order came over the telephone on the 16th, Pilot Officers Tobin, Keough, and Mamedoff ran for their Spitfires along with the other pilots of 609 Squadron. Red Tobin shouted “Saddle her up! I'm ridin’!” to his four-man ground crew—that was one thing about these Yanks, they certainly had a style all their own.

As junior men in the squadron, the Americans would be “Ass-End Charlie” in their three-man formations—weaving and turning to protect the tail of the section leader and their wingman. The only trouble was that there was no one to protect him and warn him if Messerschmitts were attacking his tail. Naturally, Ass-End Charlie did not enjoy a very long life expectancy.

At 18,000 feet, Red got the word—“OK, Charlie. Weave.” He began snaking behind the leader and his wingman, who kept flying straight and level. Over his headset, he heard someone call: “Many, many bandits, three o’clock.” He looked off to his right and could see the enemy planes, more than fifty of them. Another call said that there were more bandits at twelve o’clock, straight overhead, but Tobin could not find these. This put a scare into him; squadron veterans said that it was the ones you couldn't see that got you.

Tobin's leader went into a sharp dive, followed by his wingman. Tobin dove after them but could not see if they were diving on a target or trying to evade enemy fighters. After they pushed over, he lost sight of them. The only other plane in sight was a twin-engine Messerschmitt Bf 110, which was turning to evade him.

He closed to within firing distance of the Bf 110 but could see from his string of tracer bullets that his shots were wide. He pulled back on his stick to correct his aim. But he pulled too hard; G-forces drained the blood from his brain and he nearly blacked out. The Bf 110 was gone by the time he recovered, and he found himself all alone in the sky—not another plane to be seen, where there had been dozens only a few minutes before. With his flight leader nowhere in sight and his ammunition supply nearly gone, Tobin decided that it was time to head back to Warmwell.

When he landed, Tobin found out that all the effort had been wasted. The Luftwaffe's bombing raid had not been stopped, or even hindered. Middle Wallop (nicknamed “Center Punch” by the Americans) had been bombed for the second time that month. The airfield was still open, but just barely: the runway was cratered by bombs; some hangers and workshops had been destroyed and others were very badly damaged; and the aerodrome was dotted by unexploded bombs that threatened to go off at any time.

Warmwell, which was one of Middle Wallop's satellite airfields, had not been touched, but this was not because of 609 Squadron's efforts—the Luftwaffe had simply ignored the small field. But the Germans had tried, and succeeded, in their attacks against RAF stations all along the south coast. Ventnor radar station, on the Isle of Wight, had been knocked out. Tangmere Airfield had also been bombed, and fourteen of its planes had been destroyed on the ground (this was the day that Billy Fiske was shot down). Other airfields and vital communications stations had also been attacked and badly damaged.

All in all, it had been a highly frustrating day, both for Red Tobin and RAF Fighter Command. Tobin had burned eighty gallons of gasoline and fired two-thousand rounds of .303 ammunition, and he had not accomplished one damn thing. He had not come all the way from California for this.

Tobin, Keough and Mamedoff were not the only non-British members of 609 Squadron. Two Polish pilots were also attached to the squadron, as well as a Canadian.

The two Poles, Flying Officers Tadeusz Nowierski and Piotr Ostaszewski, had escaped to England after their country had been overrun by the Wehrmacht in 1939. Like the other Poles who flew with Fighter Command—there were three all-Polish fighter squadrons—they displayed a hatred for the Germans that astonished both the British and Americans. These Poles had seen what the Germans had done to Poland and fought with total abandon, not caring for tactics or even their own lives. They had no homes to return to and nothing to lose.

But although 609's Poles were more intense than the three Americans, the Yanks got more publicity. In fact, the three American volunteers probably received more publicity than everyone else at Warmwell combined.

The British have a curiosity about their American cousins that sometimes gets the better of them. Tobin, Keough, and Mamedoff received so much attention from the press and the other news media that a good many people became indignant. Some of their squadron mates, along with a lot of other members of the Royal Air Force, resented all this fuss. Twenty years after the Battle of Britain ended, the author of 609 Squadron's history still felt bitter about all the media coverage given to the three Americans.

But all the publicity was not entirely due to curiosity. The subject of the “Yanks in the RAF” was also a tailor-made propaganda device by which to influence the stubbornly neutral United States. The British news media was using the topic to make Americans aware that their own countrymen were already fighting the Germans in spite of the Neutrality Acts.

Most of the Americans in the British forces—serving in Bomber Command or in the navy—received little publicity or none at all. The fighter pilots, however, captured the romantic fancy of the press and public, although not even all Yank fighter pilots got their names in the paper. Most were still masquerading as Canadians and hiding from US authorities. (Technically, they were fugitives from justice.)

There were also Americans who flew in bombers, either as pilots or as members of the crew. They received a good deal less publicity than the “glamour boys” of Fighter Command. One Yank in Bomber Command, who had a few ideas of his own, was Robert S. Raymond of Kansas City, Missouri. His family was one of the pillars of Kansas City society and owned the Raymond Furniture Company. But when the war broke out in September 1939, Robert Raymond decided to join the American Volunteer Ambulance Corp—more shades of Ernest Hemingway—and set out for the fighting in Europe. He claimed that he had no romantic illusions about war, but admitted that he would be taking a financial loss by going to France to drive an ambulance.

In some ways, Raymond's story was not all that different from those of Red Tobin, Shorty Keough, and Andy Mamedoff. He arrived in France in late May, evaded the advancing German forces for the next few weeks, escaped across the border to Spain, and sailed to England from Gibraltar. In London, Raymond experienced a couple of air raids, did some sightseeing, and tried to visit Colonel Charles Sweeny. He had heard something about an all-American unit called the Eagle Squadron that Sweeny was trying to form. He never did get to meet Sweeny, but this really did not matter—Raymond had already changed his mind about joining Sweeny's organization.

Raymond had been warned against joining the Eagle Squadron by a friend who had served in the International Brigade during the Spanish Civil War. They always threw the foreigners in first, Raymond was told, so stick with the home troops. Raymond took the advice and wanted nothing to do with the Eagle Squadron.

Raymond applied to the Air Ministry in November 1940. After being tested “for everything from flat feet to vision, hearing, lungs, teeth, et cetera, and examined as to family history, algebra, geography, whether [he] could ride a horse…” he was accepted into the Royal Air Force.22

After training as a bomber pilot in Britain and in Canada, Raymond was pronounced “operational” in June 1942 and began to fly minor missions. His first fully operational tour began in October 1942, as second pilot in a four-engine Lancaster of 44 Squadron. His sorties over enemy territory included Milan, Genoa, Düsseldorf, and Nuremberg.

Robert Raymond was not the only American who served with the British bombers. William T. Kent of New York, where his father owned a nightclub, went to Canada to join the Royal Canadian Air Force. After washing out as a pilot, he applied for air-gunnery school and soon became a tail gunner in a Halifax bomber. Among the twenty-nine missions he flew were Emden, Hamburg, Berlin, and Cologne. After his tour of duty in RAF Bomber Command, he transferred to the US Army Air Force and was sent to the States as a gunnery instructor.

The British military experience of other American volunteers was eventually put to use by the United States. They were scattered throughout the bomber force, employed as navigators, air gunners, bomb aimers, and second pilots. These men helped their country in spite of its laws, although they had to become fugitives from justice in order to do so.

Among the many members of Bomber Command's “Yank Auxiliary” was Harris Goldberg of Brookline, Massachusetts. Goldberg flew 273 hours as a gunner in Wellington bombers and later transferred to the US Army Air Force. “Tex” Holland also flew in Wellingtons as a pilot. F/Lt. Joseph McCarthy was a member of 617 Squadron, the famous “Dam Buster” squadron, which flew highly secret and very dangerous operations. McCarthy came from Brooklyn, New York. He joined the RAF in 1941 and elected to remain with the British forces after the United States entered the war.

While Robert Raymond was serving with the “home troops,” his fellow countrymen in Fighter Command were learning the lessons of aerial combat, usually the hard way. Andy Mamedoff's first action came on August 24, which 609 Squadron's historian called the Luftwaffe's most aggressive and destructive day during the entire Battle of Britain. On the 24th, the German air force launched another series of massive attacks against airfields throughout southern England.

It was not a very auspicious beginning for Mamedoff. As a result of his first encounter with a Messerschmitt, his Spitfire was a complete write-off. One of the enemy pilot's 20 mm shells gutted the Spitfire. According to the damage report the shell “entered the tail of the aircraft, went straight up the fuselage, through the wireless set, [and] just pierced the armor plating behind the pilot's seat.” Luckily, Mamedoff was left with nothing more serious than a badly bruised back.23

The Yanks who had come to England to fight were not disappointed. Nearly every day from August 24 to September 6 the German air fleets turned their full attention to the destruction of Fighter Command and came very close to succeeding. The RAF's fighter units were all that prevented the Wehrmacht from invading England, and the Luftwaffe intended to inflict heavy losses upon the young Spitfire and Hurricane pilots who stood in the way.

On the day following Andy Mamedoff's brush with disaster, squadron mate Red Tobin shot down his first enemy aircraft and had a very close brush with death himself.24 The airplane that Tobin shot down was a Bf 110. After closing to within machine-gun range, he pressed the firing button and could see his bullets striking all along the twin-engine fighter's fuselage. He watched as it reared up almost vertically, stalled out, and plunged out of sight. A moment after that, he spotted another Bf 110 and went after it. He held his gunsight on the enemy aircraft's engine and pressed the firing button.

The big twin-engine fighter took hits and began to lose altitude. Tobin dove after it. When he reached the same height as the enemy fighter, Tobin yanked back on the stick to pull out of his dive. Once again, he pulled back too abruptly. The results were the same as last time—G-forces made him black out “colder than a clam.” His Spitfire spun out of control toward the Channel. When he came to, his fighter had righted itself; he was only 1,000 feet above the water.

Tobin was a bit annoyed with himself—he had finally got his first enemy airplane, but he knew that he should have had two. Still, he realized that he was lucky—he might have ended up dead, crashed in the Channel.

Red's next chance against the Luftwaffe came on September 15, which was the climax of the Battle of Britain. On this day, hundreds of Spitfires and Hurricanes—nearly two hundred over London alone—flew from their bases to intercept about two hundred German bombers and nearly twice that many fighters. Tobin's day began when a fellow pilot shook him awake just after dawn.

Red was annoyed at having his sleep interrupted and demanded to know why he should get up when it was hardly daylight. “I'm not sure, old boy,” the pilot replied. “They say there's an invasion on or something.” Tobin was more impressed with the calmness of the response than with the news itself.

Number 609 Squadron was assigned to patrol over London at altitudes between 20,000 and 25,000 feet. At about 11:30 a.m., Tobin could see more than a hundred German aircraft approaching from the south—about fifty Bf 109s at 4,000 feet above him, twenty-five twin-engine Dornier bombers below him, and twenty-five or so bombers off in the distance.

Tobin was Ass-End Charlie again, weaving behind the flight leader and his wingman. His three-man section was about to dive on the Dorniers, and he had already heard his leader call, “OK, Charlie, come on in,” when he spotted three yellow-nosed Bf 109s boring in from dead astern.

Tobin shouted a warning—“Danger, Red Section! Danger! Danger! Danger! Danger!”—throttled back, and kicked his Spitfire into a 360-degree turn. The three Messerschmitts could not slow down from their dive and overshot him. Tobin fired a burst from his eight .303 Browning machine guns at the last of the planes and saw smoke trail from it. All three enemy fighters then disappeared.

By this time, Red was down to about 8,000 feet. He pulled the stick back and began climbing; at about 10,000 feet, he spotted a lone Dornier Do 215 below him heading for a cloud bank. The lanky redhead pushed his throttle and control stick forward, diving on the Dornier before it could reach safety.

It did not take long for the Spitfire to overtake the bomber. As soon as he was within range, Tobin thumbed the firing button. He could see his bullets hitting the Dornier's port aileron—after a second or two, it was completely perforated with bullet holes. An instant later, the stricken bomber's port engine began trailing a stream of white vapor.

“I followed him down,” Tobin recalled, “and saw a Dornier 215 make a crash landing two or three miles from Biggin Hill. Three of the crew got out and sat on the wing.”

Pilot Officer Tobin had another enemy aircraft confirmed as destroyed, as well as a Bf 109 damaged. This time he remembered not to pull back on the stick too sharply and did not knock himself out with G-forces. He was learning. So were his fellow Americans Shorty Keough and Andy Mamedoff.

Between the three of them, the Yanks accounted for three enemy aircraft destroyed during the Battle of Britain. This may seem a trifling number when compared with the spectacular scores posited by some of the leading aces on both sides, but most fighter pilots who took part in the Battle were not credited with any confirmed victories at all, not even one German airplane shot down.

Tobin was credited with two German aircraft destroyed. Keough and Mamedoff each received credit for half a victory. Shorty Keogh's half-kill, which he shared with a pilot from another squadron, was also a Dornier 215 and also came on September 15.

The Battle of Britain did not end on September 15, although the Air Ministry's designation of it being “the Greatest Day” was not an exaggeration. Aerial combat between the Luftwaffe and Fighter Command continued on throughout September and October—on October 29, for instance, the Luftwaffe lost thirty-one aircraft and the RAF lost eighteen—and the Blitz against London and other British cities went on until May 1941.

But the Luftwaffe's losses on September 15—originally reported as 185 aircraft, but reduced to sixty or fifty-six or fifty by more objective postwar accounts (depending upon which source, German or British, is consulted)—persuaded the German High Command to postpone their planned invasion of England. The invasion, code-named “Operation Sea Lion,” was pushed back to September 21. On September 21, it was postponed “indefinitely.” Not many people knew it at the time, but Britain was safe from Hitler and his Wehrmacht after September 15.

Four days after taking part in the great air battle, Red Tobin, Shorty Keough, and Andy Mamedoff were posted to Church Fenton, Yorkshire, where the first all-American “Eagle Squadron” was being formed. According to RAF records, Tobin, Keough, and Mamedoff were the original Eagles, the first members of 71 (Eagle) Squadron. Their squadronmates in 609 were sorry to lose the wisecracking Yanks who'd been with them for only about six weeks. They were leaving “just as they were becoming really good,” according to one pilot. The squadron would be losing three pilots and were also being deprived of a source of constant amusement.25

During their time with 609 Squadron, the three had picked up quite a few tricks of the fighter pilot's trade—the fine points of tactics and deflection shooting; the value of conserving ammunition. They would do their best to pass these vital skills along to the rookie members of the Eagle Squadron. If the new batch of volunteers hoped to survive their first encounters with the Luftwaffe, they would need all the coaching and instruction they could get.

Nobody really knows how many Americans served with Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain (or, for that matter, with Bomber Command). The Neutrality Acts prevented most of them from declaring their true nationality. But there were at least twelve—enough pilots to man an entire squadron. (There were probably many times more than twelve, but any sort of estimate would be nothing but guesswork.) By September 1942, when the Eagle Squadrons were absorbed into the US Army Air Force, more than one thousand Americans were serving in the RAF. Nobody can be absolutely sure how many enemy aircraft the Americans shot down either, but the count comes to at least 21 ½—almost two full Luftwaffe squadrons.

Clearly the Yanks were skilled pilots, yet in the eyes of the Air Ministry and Winston Churchill's government, the real advantage of having them in the RAF was their propaganda value. As many British pilots noted, with a good deal of resentment and jealousy, the Yanks certainly did get a lot of publicity. From the government's way of looking at the situation, all the Yank publicity might help to make American opinion more pro-British.

It was difficult to make the most of the situation because the American volunteers were scattered throughout Fighter Command, serving in several squadrons. (The seven “official” Americans, that is.) If there could be an entire squadron of Americans in the Royal Air Force, it would be an even greater source of publicity. The American public could then be shown that their fellow countrymen were taking part in the war as a body, not just as a few adventurous (cynics would say “scatterbrained”) individuals.

The Air Ministry could also use some favorable publicity for its own purposes—getting the RAF into the newsreels never hurt. The additional volunteer replacements would also be welcome since its fighter squadrons had been decimated by the Luftwaffe. The Air Ministry decided to adopt Colonel Charles Sweeny's idea of forming a squadron made up entirely of Americans. A British officer would have to command the all-American squadron, of course. The Yanks could not be trusted that far; somebody responsible would have to keep an eye on them.

And so, a unique chapter in Anglo-American history was about to begin. One British observer called the Eagle Squadron a “unique institution.” Notably, the same phrase has also been used to describe both marriage and slavery.26