The announcement of the postings for the student pilots of No. 40 Course at RAF Valley in August 1968 was not just a huge sense of relief at having passed a gruelling flying course, it was an unbelievable moment in my life when a dream came true. Postings to Lightnings, Hunters, Canberras and CFS had been announced, but the best had been saved till last: ‘Buccaneer for Al Beaton and Bill Cope’. We were the initial RAF first tourists posted to the exciting new low-level combat aircraft that was just entering service. We had timed it perfectly and were the centre of congratulations mixed with a fair measure of envy but I just remember feeling incredibly lucky.

The pre-Buccaneer weapons course on the Hunter at RAF Chivenor was a return to the reality of hard work and another test of self-confidence. We were only twenty-one years old and were now flying a single-seat thoroughbred that initially took us on the ride of our lives. Bombing and rocketing, and the precision required, became a new discipline that had to take over from the excitement of flying. Scores and results were facts none of us could argue with. Then came the low-level thrash around Wales and Devon, with a bounce aircraft to avoid, all ending up with a first-run attack (FRA) bomb or rocket on the range at Pembrey.

We were only just beginning to get to grips with the aircraft and the applied flying skills when the course came to an end. We felt lucky to have flown the Hunter, which had provided a stern test and made us confident and ready for the next important step. We had proved to ourselves, and the RAF, that we had the determination to be successful and that we possessed the fundamental skills to fly one of her majesty’s expensive toys. Our spirits were high, and the more advanced Buccaneer was now in our sights. Failure just wasn’t an option.

In February 1970 we headed for Lossiemouth and the free airspace and beautiful northwest Highlands and the Moray coastline, which were the Buccaneer’s home territory. North Wales and the A5 pass were supposed to be spectacular but the freedom to fly around Scotland at low level and to bomb on the excellent range at Tain provided the best facilities available. The Fleet Air Arm (FAA) approach on 736 Squadron was reassuringly relaxed after the more formal RAF style and the friendly, encouraging and competitive squadron spirit was ideal for us to make our final step to a front-line squadron. The last and most important ingredient of all, the mighty aeroplane itself, was the ultimate exhilaration.

Ground school introduced us to new navigational equipment, Blue Parrot radar and Blue Jacket doppler, a weapon-aiming system that was much more advanced than stopwatch and map. For the first time we were crewed up with our fellow first-tour navigators. Navigator training in the RAF had hardly recognised the low-level environment and their lead-in had been minimal compared to our pilot training. Throw in the avionics and the high-speed low-level tactics with a bounce, plus weapon handling and operating a radar and our first-tour navigators had their work cut out from the very beginning. Neither of our two navigators survived the course. In my mind, this was in no way a reflection on their enthusiasm and potential but highlighted the inadequate RAF pre-OCU navigator training.

With no dual-control Buccaneer, we were introduced to the aircraft’s instrumentation with four or five sorties in modified two-seat hunters. Our five simulator trips in the motionless ‘box’ sufficed to familiarise us with all the systems. Flap, droop and boundary layer control (BLC), or ‘blow’ as we called it, was a new concept to master. I soon disciplined myself to watch the cheeses [gauges] that signalled the position for flap and droop. Two engines, and therefore two throttles, was a first. I convinced myself that if I simply moved both throttles together it was effectively one power unit.

The simulator had prepared us for our first Buccaneer ride when there would be no demos. We would be on our own but after this introduction I remember thinking that I should be able to take off and land safely so my first flight in the Buccaneer was something to really look forward to.

My overriding impression of my first ‘solo’ was the aircraft’s sheer size. The climb up the ladder into the cockpit to sit in the real thing for the first time was a moment cut all too short by the need to get on with the pre-flight checks.

Tom Eeles had the dubious honour of sitting in the back. Up until now, all of our pilot training had been geared towards single-pilot operation and we had had experience of taking off and landing in a number of aircraft. Now we had to cope with flap, droop and the blow, and they were critical additional factors in the Buccaneer. The take-off was exhilarating and having Tom talk me through cleaning up the aircraft as we accelerated away was a great comfort. To share a discussion or a decision was a pleasant change and very reassuring. Fulfilling an ambition, and in the wonderful surroundings of the Moray Firth on a fine sunny day, was a most exciting flying experience and one I, like all Buccaneer pilots, will never forget. As I savoured this first experience of the mighty Buccaneer, it had all the ingredients and excitement of another first solo. I was aware of the remarkably positive handling characteristics of the clean aeroplane at medium level. This was a comfortable aeroplane to fly. As the sortie progressed I realised that I would soon have to return this beast to earth again, and being the only one with a set of flying controls, this was going to require a serious focus of my attention. A few dummy circuits at a safe height prepared me well for the challenge ahead.

Back to the circuit, the acid test was the final approach and landing and it was reassuring to have Tom’s commentary and to see the cheeses and the blow working just as advertised. The carrier landing techniques we were taught using the ‘meatball’ deck-landing mirror sight on the edge of Lossiemouth’s generous runway was a wonderful approach aid. This aeroplane was to be set up from several hundred feet out and, with an ideally-positioned ASI and the mirror sight both displayed within the front left windscreen, it was flown as precisely as possible down to the ground with no flare. The addition of the ADD (airflow direction detector) tone was another quality item that the Buccaneer introduced us to. We could now also hear how accurately the aircraft was being flown. Visual and audio senses were tuned to achieve the steady note for a very meticulous approach. Simple really! With the almost unbreakable main undercarriage playing its vital role, I landed safely. So it was that both Tom and I survived, my pride and his relief both scoring straight tens.

The aircraft was very responsive and solid in a crisp manner. Whilst it didn’t handle as lightly as a Hunter there was never any shortage of control authority to meet the demands of high speed and high rates of manoeuvre, either in the bombing pattern or in the most exhilarating low flying. In the circuit, you just had to be more precise. Crew co-operation continued into the circuit handling, particularly observing the flap and droop and blow. The talking checklist with another pair of eyes (and opinion) in the cockpit certainly lightened the load. Thus we all had a great deal of confidence and a growing affection for the airframe, although we were less sure about the performance of the avionics suite. If there was any significant cross-wind on take-off, the Gyron Junior engines might not wind up, smoothly, the inlet guide vanes (IGV) usually stalling and causing the engine to surge. The first time this happened to me I thought the aircraft was being hit by cannon shells such was the rapidity and the violence of the surging engine. Power on one engine was less than adequate on the Mark 1 and we all knew it, particularly for any single-engine overshoot.

Barry Dove next found himself on the programme to fly my Fam 2. In many ways, flying with an experienced navigator was probably more valuable than having a QFI in the back. Sorry, Tom! The senior navs had seen it all, good and bad. They had no flying controls to retrieve a situation and their focus, sense of survival and professionalism were invaluable. They were another pair of eyes on the essential instruments and certainly had strong views on where and how the aircraft should be flown. They weren’t really navigators at all; they were part of a two-man team whose responsibility, through training, discussion and agreement, was to make the Buccaneer operate effectively in the low-level environment. We didn’t think it was dangerous; after all, it was the best fun flying to be had in the whole of the RAF. In the low-level role, it was two guys, an aeroplane and the weather. There was no time to refer to rulebooks. Respect the regulations yes, but developing flexibility and operational effectiveness, whilst operating this large machine at low level and out of reach of any ultimate controlling authority, required an attitude of mind that the FAA had and the RAF was learning.

The all-round view from the Buccaneer was excellent and the smooth ride lent itself to low-level flying. Flying at high speed, close to the ground or over the sea was exhilarating and gave a total sense of freedom. Together with a disciplined measure of controlled hooliganism that low level brings, and which no other role can provide, it was every young pilot’s dream.

On the weapons range, the modern strike sight was a great step up from the earlier generation system in the Hunter. But the Buccaneer’s system really came into its own for medium toss bombing. Running in past Tarbat Ness and tossing bombs on to Tain range from three miles was very different to anything we had done before.

We only flew the Mark 2 five times on our course but I distinctly remember the awesome power of the Spey engines compared to the Mark 1’s underpowered Gyron Juniors. The next first tourist course had less luck and lost two aircraft, both in the circuit on student fam sorties and, very sadly, one navigator was killed when his seat failed to operate correctly. Attending his funeral was a most moving experience for all the new Buccaneer aircrew and another new self-discipline that we would, unfortunately, have to call on several times again in our Buccaneer experience.

It was early July 1970. With only seventy-five hours on type, we finished the course with a flourish throwing Gloworms over Gralis Sgeir at night, almost just for the hell of it as they provided virtually no useful illumination. During our course we had been introduced to low-level navigation, strike progression, numerous bombing modes, including dropping our first live 1,000lb bomb, some two-inch RP, and a great deal of Lossiemouth and local Moray hospitality. We were well prepared to return to the RAF and join a squadron.

The spirit on 736 Squadron was a breath of fresh air to we first tourists. There had been too many prima-donnas in the Hunter world at Chivenor. We were operating to far greater levels of operational flexibility and achievement, the two-man principle eliminating the bullsh** and replacing it with a squadron spirit that swept us up and carried us with it throughout the course. We weren’t just students, we were treated as squadron members and the sense of belonging in our formative Buccaneer days was a huge bonus which paid handsome dividends later. It certainly helped us tremendously throughout the course and flying with the navy had added another dimension and would be the foundation upon which our own personal and the RAF’s Buccaneer force would build.

The early crews for the RAF’s first Buccaneer squadron, No. 12, had also completed their courses at Lossiemouth. The CO, Wg Cdr Geoff Davies, had been a test pilot on the Buccaneer. His experience of the aeroplane was greater than any of us although it was primarily Mark 1 time on radar-development trials with Ferranti. Others came from a Canberra background so had experience of the all-important two-man principle. The flight commander was Ian Henderson, in my view one of the most gifted Buccaneer pilots who we all came to respect.

When we arrived at Honington it was to discover that the squadron was away in Malta on an exercise. Feeling deserted at the outset, our typical first tourist desire to keep the 736 momentum going was frustrated but we soon learned our proper place; after all, we were the junior pilots. However, that did not stop us enjoying this new phase of life, the thrill of arriving on our first squadron, fabulous flying, the team spirit, a large collection of single guys, a vibrant officers’ mess, good local pubs, all were ingredients that invited us to enjoy life to the full and we did.

12 Squadron investigate a Soviet Kotlin class destroyer in the Mediterranean, 1970.

Our flying on 12 Squadron began with the standard routine of acceptance checks in both the Hunter and the Buccaneer. We now had to work up to become operational. Our role was two-fold; maritime attack and nuclear strike. The aircraft had been brought into service after the demise of both the TSR2 and the F-111. The nuclear role was a sobering thought for a young twenty-two-year old when struggling to mix the new found freedoms of squadron life with the distractions of Green King at the Four Horse Shoes at Thornham Magna and other similar hostelries of Suffolk and Norfolk.

At this early stage, maritime tactics sorties did not feature regularly and our 1 (Bomber) Group master, with its long-standing bomber mentality and years of operating the V-Force, appeared to struggle on how to include the Buccaneer in its arsenal. During my later tours I saw how the Buccaneer squadrons became a formidable maritime attack force. To my mind we weren’t a conventional maritime attack squadron at all. Throwing a tactical nuke, from three or four miles away was what the aircraft was designed for and this option gave us the only chance of damaging a naval target and surviving. Delivering iron bombs against a modern well-defended naval force was, in reality, a combination of suicide and a complete waste of time. We were joining the UK nuclear strike force primarily and, with its long legs, the Buccaneer, even without using air-to-air refuelling, could strike at very long range and deep into Eastern Europe. The Cold War was in full swing and the thought that the Soviet army could be at the Rhine in three days focused our minds on overland bombing. However, with the demise of the future aircraft carrier programme, the RAF Buccaneer force had been tasked with providing land-based support of maritime operations and so we got used to enjoying the Buccaneer’s multi-role capabilities.

Our early sorties on the squadron were spent bombing on the ranges close to our new patch. We were lucky to have Holbeach, Cowden and Theddlethorpe for laydown and dive-bombing and Wainfleet for toss. The Buccaneer was a good weapons platform and I recall it was slightly less stable in yaw than it was in pitch. Avoiding any pedalling on the rudders was important and matching the LP RPMs was essential to obtain balanced thrust from both engines. ADSL (auto depressed sight line) bombing, requiring steady tracking as the bunt increased to an automatic weapon release, was very accurate but very academic. In an operational scenario against a determined opponent, a pop-up attack was more realistic so we adapted a profile before pulling up for a low-level ADSL release.

Always an excellent service from our Victor friends.

Our use of two-inch RP was great fun, especially loosing off a full pod of them, but it was not expected that many maritime targets would be engaged with rockets. Later, when SNEB replaced the RP, we developed tactics against fast patrol boats. Just as much fun were dive attacks against a splash target towed by a ship or launch. We also introduced the Lepus flare at this early stage and it made for an exciting sortie when we flew at night, tossed a Lepus and then dived to attack beneath the illumination.

This wide variety of weapons gave us many options and we even had an excellent photo-recce capability but it was difficult at times to stay current in every mode, particularly when some flying hours had to be devoted to completing the dreaded ‘basic training requirements’ (BTR) of GCAs, single-engine approaches etc., etc.

I always felt that the Buccaneer was well ahead of its time. It was great to fly but just when we thought we had mastered one game, there was always something else for us to explore. It is little wonder that we enjoyed operating the aircraft and gained great respect for its capabilities. The Mark 2 Buccaneer reversed the trend of most British military aircraft designs by providing more than enough power for the majority of tasks, especially heavily laden with fuel or 1,000lb bombs. The fuel-carrying capability was another tremendous comfort, not just as a long-range strike aircraft but also allowing us to outrun most fighter adversaries who were always likely to be fuel critical before us. That ability to outperform anything at low level gained us a respect that we became very proud of and it boosted our morale.

As the squadron developed, we became a class act and the envy of many of our contemporaries in the RAF. The role and the aircraft were everything and more than we had all ever wanted. The two-man crew concept stifled any individual arrogance whilst undoubtedly increasing operational efficiency. It was the ideal world for us as first tourists. This was an aircraft that was supreme in its own environment; the opposition didn’t need to know that the avionics – the weakest link in the aircraft – were frustrating the hell out of the navs. I recall reflecting that there was little point in getting through at low level if the avionics kit wasn’t working. In the front seat, we gained the greatest respect for our navs, who with their heads down, whilst we flew fast and low, were trying to salvage something out of kit that was not as robust and reliable as the roles demanded. Mutual respect for each other was building and maturing the squadron all the time. When we finally added air-to-air refuelling to our bag of tricks, not only from the Victor but also using our own buddy-buddy aircraft, our operational flexibility was complete. There was now no limit to where we could go, either by day or by night.

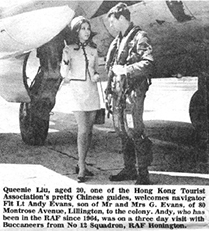

That finally led us to the best part of squadron life, detachments to Norway, Cyprus, Italy, Malta, Stornoway and even back up to Lossiemouth exercising what we had practised from Honington. For me, the detachment to beat them all was to Tengah, Singapore, in February 1972 where, after a four-day transit with AAR, through Cyprus, Masirah and Gan to Singapore, we mixed flying over the jungle with the attractions of down-town Singapore and lots of cold Tiger beers. As I landed my Buccaneer on Malaysian tarmac, I felt a true feeling of personal achievement.

That we all have such memories of our own, of great friendships all linked to a most wonderful flying machine, is a true testament to its capability and its contribution in enriching the lives of all of us who flew the Buccaneer. This was without doubt the finest flying time of our lives. For a first tourist, I can still hardly believe my luck.

Welcome to Hong Kong.