Maritime tactics were constantly evolving during the 1970s and two of the Buccaneer’s most experienced QWIs were Bruce Chapple and Mick Whybro and here they discuss some of 12 Squadron’s activities during this period.

When 12 Squadron formed with the Buccaneer in 1969, it was the first time the RAF had had a maritime strike role since the days of the Beaufighter and Mosquito Strike Wings of Coastal Command during World War Two. They had found it essential to know exactly where targets were before mounting a co-ordinated attack. A probe aircraft was sent ahead to radio back exact positions so that the strike leader could organise and position his force of torpedo-carrying and rocket-armed aircraft to make the attack.

Little had changed since those days except our need for support was even greater as we operated at much longer range and, therefore, far larger sea areas had to be combed in order to find the target. We set about developing these World War Two tactics to suit our capabilities and over the next twenty years they were refined as new weapons were introduced into our inventory.

During an exercise in the Mediterranean in 1970 ‘shadow support’ was developed using Victor strategic reconnaissance aircraft. The navigator/radar plotted the ship contacts over a wide area and over a period of time. He monitored sailing patterns when those contacts manoeuvring could be identified from those making steady passage along known shipping lanes. These contacts could then be carefully monitored and their position was passed in a simple code to attacking aircraft.

In due course, the Vulcans of 27 Squadron were tasked exclusively in this shadowing role. Their crews became expert at identifying targets in a cluttered sea area and new methods of passing coded dispositions were developed; the process became known as maritime radar reconnaissance (MRR). Canberras and Buccaneers flying low-level probe (LOPRO) sorties were often launched to identify the targets.

During Exercise Dawn Patrol in the Mediterranean in 1974 my nav and I were tasked to fly a LOPRO sortie as a singleton to sniff out the target, the US Sixth Fleet no less. We flew at very low level and received support from the MRR Vulcans. The task was to probe the fleet, clear the area and report back the disposition to the attacking formation via the Vulcan. We carried full fuel, anti-radar Martel missiles and were fitted with a passive radar-warning receiver (RWR).

A high-pressure weather system with a temperature inversion prevailed, an ideal situation for ‘anaprop’ where electronic transmissions can be bounced between the inversion and the sea surface in a sine wave which, under favourable circumstances, allows passive detection from beyond the normal radar horizon; on this occasion, flying at 100 feet, we got an RWR intercept on the Sixth Fleet search radar at 160 miles. After a thirty-degree turn onto a diverging heading held for about twenty minutes we headed back towards the fleet and got a further position line, which gave a fairly accurate fix.

As usual, the ship’s ‘safety cell’ failed to respond to our request for a low-level fly-through but we pressed on. No fire-control radars were detected as we made a rapid exit to a safe distance to transmit a position and disposition report for the attack formation. The safety cell were called again at which point all hell broke loose as every fire-control radar fired up! (it should be noted that the safety cell were supposed to be independent of the defence cell.)

With large areas of ocean devoid of enemy activity, the standard profile adopted by a Buccaneer maritime attack formation was a Hi-Lo-Hi. This had the added advantage of extending the range to as much as 600 miles radius and this was regularly augmented by the use of air-to-air refuelling. Whenever possible, formations were made up of six or eight aircraft and during the transit to the target area in wide battle formation, all the crews listened out on the radios for the latest information on target locations. All aircraft maintained radio and radar silence to avoid giving away their approach to a target. At a range of 240 miles from the target the formation started an ‘under the radar lobe’ descent to sea level in order to stay outside the enemy’s radar cover. During the descent the RWR was monitored for selected search radar frequencies and, if one was detected, the rate of descent was increased to remain outside the detection range. At thirty miles the leader ‘popped up’ and the navigator switched on his Blue Parrot radar for two or three sweeps during which time he identified and ‘marked’ the target before descending back to 100 feet. After choosing the radar return that was assessed to be the ‘high-value target’, the lead navigator then had to convey the information verbally over the radio to the rest of the formation and this created problems.

The plan sounded good in principle, but had some drawbacks, not least the ambient noise in the cockpit at high speeds, which made it difficult to understand all but the simplest messages. This was exacerbated when a senior navigator on the squadron insisted on his own solution – a lengthy dissertation over the radio describing all the contacts he could see on his radar screen. Didn’t work. After a particularly ‘lively’ debrief, it was suggested from the floor, that perhaps the situation might be improved if the attack message was passed by someone with ‘more than half a brain and without a speech impediment’.

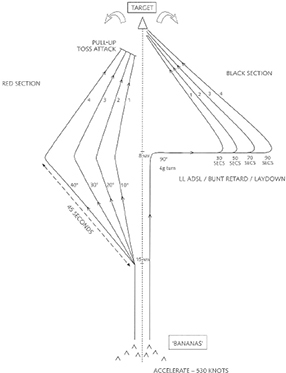

During this period, the US Navy exchange officer, Bill Butler, suggested quietly that if the doppler-stabilised radar track marker was used, and a suitable range ring was selected on the radar, the lead aircraft could turn to put the most likely radar return on the track marker line (the rest of the formation paralleled the leader’s heading), and fly it down the track marker line until the radar return coincided with the range ring, all that was needed was a simple codeword recognisable even in poor radio conditions to convey the mark to the formation. This suggestion was taken up, tried in the air, and found to be a brilliant, simple and consistent solution. The codeword? ‘Bananas!’ it was never changed, and it became the trademark attack call of the Buccaneer force – usually followed by a split! And so, the Alpha attack was born.

An Alpha Attack.

At the pre-sortie briefing one of a number of Alpha coordinated attack profiles was selected as the primary option. Each was designed to provide a multi-axis co-ordinated attack depending on the defences of the planned target. The leader could change the option at short notice if weather or enemy ship dispositions dictated different tactics, and the new Alpha attack was broadcast with the Bananas call. Radio transmissions were kept to an absolute minimum. Accelerations were never called but were based on the leader’s smoke emissions from the engines. All turns were with sixty degrees of bank and timing started from the beginning of the turn. In total radio silence Bananas was not called, but the leader rocked his wings and the split was executed as soon as the leader started his turn.

The aim of the Alpha attacks was to maintain the element of surprise for as long as possible and to confuse the target defences and delay the lock-on solutions for their radar-laid anti-aircraft defences. Once we had penetrated the target ship’s weapons engagement zones, we used the exceptional low-flying performance of the Buccaneer to fly at high speed and ultra-low level and still be able to sustain high-g manoeuvres to increase the tracking problems of the enemy radars. The first attacks were delivered from a toss delivery at three miles on converging headings. Each bomb was fused to explode at sixty feet, with the aim of destroying the fire-control radars and incapacitating the missile and gun crews. In the meantime, the attack force had turned starboard through ninety degrees before rolling in to release four to six 1,000lb bombs independently from a low-level dive or laydown attack that provided the killing blow. Timing was critical if aircraft were to avoid the debris from the preceding attack. The obvious weakness of this attack was the vulnerability of the aircraft – particularly those that carried out the precision attack.

Some ‘attacks’ on major exercises required a degree of skulduggery if honour was to be preserved amongst our NATO allies. The American Sixth Fleet was always high on our target list for such activity. On another ‘Dawn Patrol’ we were tasked against a CAG (carrier air group), which included the USS America, which was low in the water weighed down by the admiral’s staff and attendant sycophants; the group was to the west of Sicily and doubtless expected the Buccaneers to attack from the east. Unfortunately for our transatlantic cousins, who had no idea of the radius of action of the Buccaneer, the team planned to go north to Palermo along the track of the airway, but not in it, then descend to low level like a formation of cast-iron manhole covers – as only the Buccaneer could when using full airbrake – and disappear from the CAG’s radar plot.

When at low level, we manoeuvred to attack from the west i.e. from ‘behind’ the fleet. With no reply from the safety cell (again!) the attack was carried out, the formation reformed at twenty miles followed by the normal courtesy ultra-low level flypast and climb out during which an American voice on the radio asked who we were and what were we doing. After landing it transpired that the admiral’s staff had not had a good day with numbers so we sent them a chatty little signal explaining which calendar was in use and which time zone they were in. An apologetic signal followed requesting a rematch some forty-eight hours later.

The squadron obliged using the same profile, attacked the CAG and reformed without being illuminated by any defensive radar. It was not until the farewell flypast that any sign of activity became apparent; as the Buccaneers stormed past either side of the carrier marginally above the wave tops, the five-minute defensive F-4 fighter cap was being launched to intercept the attack – too late! interestingly my directional consultant in the back seat for this sortie was Bill Butler USN whose previous tour had been on board the USS America and whose contribution to the squadron tactics was invaluable.

Co-ordinated attacks were also practised at night, but with formations of four aircraft operating at a minimum height of 200 feet, which required considerable concentration. The principle was similar to the day profiles, but the precision low-level bombing was avoided and the preferred delivery mode was medium toss, giving a degree of ‘stand-off’. There were two periods that required particular attention. The first was the 4g recovery from the toss delivery, which required 135-degree angle of bank, until the nose passed through the horizon, when the bank was reduced to ninety degrees and the aircraft dived for the sanctuary of low level. The second was the formation re-join in the very dark conditions, which was time consuming and disorientating.

Less well-defended targets, such as fast patrol boats (FPB) were attacked in the dark using Lepus illumination flares thrown by the lead aircraft of a pair. As they approached the target, the No.2 aircraft dropped astern when the cloud base dictated the trail distance. The lower the cloud, the later the ‘flare show’, and so the trail distance had to be increased. The leader tossed the flares to deliver them ahead of, and beyond, the target and the second aircraft attacked with SNEB rockets or, occasionally, bombs, with the target silhouetted in the light lane created by the flares.

Whilst the No.2 attacked using a ten-degree dive profile, the leader regained control from the Lepus toss delivery and made a follow-up attack. During the toss recovery, a great amount of hands flashing round the cockpit took place – a prime situation for disorientation – in order to select switches for the next attack. During this interesting whirling dervish act, the No.2 took the lead, flew a racetrack pattern and made a second flare delivery followed by the leader firing his rockets. What made life particularly interesting during the attack was that the three flares were given different ‘flare height settings’, which meant that they were not in a horizontal line or in line with subsequent dive attacks. In addition, there always seemed to be one at twelve o’clock high during the 5g recoveries from the dive attacks. All very disorientating. During an exercise in the Baltic, one pair managed to get six flares burning at the same time, i.e. four attacks in four minutes. The FPBs were suitably baffled by the almost daylight conditions provided as were the innocent ships plying their sedate passage in the dark waters of the Skagerrak that night.

During 1974 the squadron deployed to the Royal Norwegian Air Force base at Bardufoss situated well inside the Arctic Circle. As part of the exercise we were tasked against the local FPBs. The Royal Norwegian Navy is particularly adept at camouflage and after about twenty minutes of fruitless cruising up and down the exercise area we had seen nothing; more in hope than anything else we pulled up and tipped in at a promising group of rocks at which point two of the ‘rocks’ crash started and departed at about forty knots! (The FPBs had moored up against the reef of rocks with camouflage nets deployed.)

There ensued an interesting and eye-catching engagement setting up coordinated dive attacks whilst avoiding the more vertical parts of the scenery and countering the FPB’s high-speed defensive manoeuvres. Great enjoyment and we were happy to be invited back.

––––––––

By the mid-1970s it had become clear that it was essential to have a stand-off capability when attacking ships with increasingly capable, and lethal, anti-aircraft defences. Mick Whybro takes up the story.

Gp Capt John Herrington congratulates Mick Whybro on being the first to achieve 1,000 hours on the Buccaneer.

Back in 1966 I came to the end of my first tour, a brilliant three years at Akrotiri in Cyprus. I had been a member of that premier Canberra ground-attack squadron, ‘Shiney 6’ (opposition squadrons used a less polite name) when the world was our oyster. We flew to Singapore in the east, as far south as Salisbury (Harare nowadays), to Gibraltar in the west, north to the UK and everywhere in between. We had a ball, there was never a dull moment. I thought that any ensuing postings could not possibly live up to my first one. How wrong was I?

I was extremely fortunate to be posted to the far north of Scotland to HMS Fulmar (Lossiemouth) for loan service with the Fleet Air Arm flying the Buccaneer. Little did I know that I was to remain with the Royal Navy for five years (the highlight of my thirty-three years service) and followed by five years RAF Buccaneer flying. All in all, a really satisfying and enjoyable time, with the ‘fun needle’ always in the green.

By the time I was on my final Buccaneer tour, I was a steely QWI (the cream of the cream) on 12 Squadron based at Honington. The squadron was a maritime-attack outfit and the first to employ TV Martel. The missile was designed for use against a spectrum of targets, but was acquired by the RAF for the anti-shipping role. In addition to the missiles, the aircraft carried a data-link pod that provided the link between the navigator and the missile. The rear cockpit contained a TV screen and control facility.

The missile was launched from 100 feet above sea level at around 500 knots at fifteen miles from the target. On release the weapon climbed to its mid-course altitude somewhere between 1,500 to 2,000 feet. The navigator was able to side step the missile (really intended for overland use to enable the operator to do some TV map reading – not easy), and to down-step the missile in order to remain below cloud. He also had the ability to pan the camera in the nose of the missile left and right in order to facilitate early target acquisition, which was dependent on the prevailing visibility. Once visual with the target, which ideally would be when it appeared at the top of the TV screen, the navigator would wait until it reached mid-screen and select terminal phase (TP); he now had full control over the missile’s flight path, up/down as well as left/right in order to fly the weapon into the target by maintaining the generated cross-wires on the aiming point.

A 12 Squadron Buccaneer armed with one AR Martel, 2 TV Martels and the TV data link pod.

The point at which TP was selected was fairly critical; too far out would tend to result in a long shallow approach which would be difficult to control in the last few seconds to impact; too close would result in a rapid nose-down command and a very short time of controlled flight. Another problem, which the navigators usually mastered with adequate training, was the control ‘stick’ which positioned the cross-wires over the aiming point. It worked in the opposite sense to the hand controller we used to position the aircraft radar marker. And, it favoured right-handed operators (watch this space) – pilots would not have coped.

All the early work on the TV Martel and associated systems was carried out at Boscombe Down, culminating in a ‘live’ missile at Aberporth range against a warship target. The next milestone occurred in October 1974 when Trial mistico allowed for six inert missiles to be fired from within the resources of 12 Squadron. Although the Central Trials and Tactics Organisation (CTTO) oversaw the trial, the Honington wing weapons officer managed it. Paddy O’Shea was a larger than life Irishman who was one of the leading lights in the Boscombe trials and what the burly rugby playing and hard-drinking Irishman said the navigators did their utmost to achieve! Before the trial the firing navigators were required to complete hundreds of runs in the TP simulator. This presented them with just about every possible situation they could find on selection of TP. In addition, aircraft could be fitted with a TV Airborne Trainer (TVAT), which was virtually the TV part of the actual missile.

During a routine training sortie the navigator could select a suitable ‘legitimate’ ship target and practise tracking. The operator would con the pilot as though he was ‘flying’ the missile and talk him down to a successful conclusion, with break-off in the ensuing dive at the pilot’s discretion; it’s fair to say that some were quite sporting! The pilots could also practise the breakaway manoeuvre required immediately after the missile launch. This was a 3-4g level turn at launch height away from the target ensuring that the data-link pod remained on the target side of the aircraft. The turn continued through 120 degrees where the aircraft was rolled out maintaining direction until impact. On an actual firing run the navigator would experience this breakaway manoeuvre with the sea streaking past his left ear at 100 feet in a 4g turn while his TV screen told him that he was straight and level at 1,500 feet. This was a discomfiting experience only stomached by extraordinary mortals.

This first Trial Mistico lost some realism for the crews when Aberporth range authorities insisted on having full control over the positioning of the launch aircraft and the actual launch point in order to fulfil the constraints of a tight safety trace. Overall, the squadron performed admirably with no major problems resulting in six direct hits on the target. (The target was a 30-foot long raft with a vertical structure towards one end with three 15-foot square sides, the centre of the facing panel being the aiming point.)

The second Trial Mistico occurred twelve months later. Although still run under the auspices of CTTO, this trial was organised by the squadron when I was detailed to run events. The plus side of this was that I got to fire a second missile. One of the basic requirements was that the ‘firers’ should not be the six who took part in the first trial. However, the boss, who was new, was allocated a missile and I was his navigator. The major change for this phase of the trial was that the Aberporth authorities agreed to allow crews to navigate themselves to the launch box and the firing position with no assistance (interference?) from themselves, apart from a mandatory ‘STOP, STOP, STOP’ – a measure they had no need to employ. As with the previous year, the trial was successful, but with only five out of six direct hits. The missile that missed was pretty spectacular nonetheless.

CTTO in their wisdom decided to run a joint trial with Mistico, which was to evaluate the RAF Phantom’s radar performance in acquiring and tracking a TV Martel missile, head-on from launch to impact. Thus, they were approaching the raft target from the opposite line of attack. Apparently the Phantom navigator managed this quite successfully. However, the TV Martel on this particular day did not perform as advertised or with the same degree of success. Upon selecting TP, the navigator, in the guise of a first-class, left-handed ‘dark blue’ navy observer, found that he had no elevation control over the missile, which promptly went into a steep climb. The cloud over the target was a complete blanket at 2,000 feet. Our hapless observer had a clear picture on his TV screen of the missile entering cloud, emerging into clear air at 5,000 feet and then a dark blur which was a Phantom in close proximity. Needless to say, the Phantom pilot had the shock of his life when a large thirteen-foot drainpipe appeared going vertical in front of his nose. The range controller subsequently sprang into action and destroyed the missile before it left the safety trace. Poor old Ken (for that was his name) was ribbed mercilessly, particularly as he was a left-handed operator using a right-handed system! he was of course blameless – although we were slow to admit that to him.

Soon after this trial, and after some ten years flying the mighty Buccaneer, I was inevitably nobbled for a ground tour at group headquarters; at least it was a Buccaneer associated job, working with some old ‘colourful’ colleagues, so we could still reminisce and tell war stories, much to the annoyance of our V-bomber ‘friends’.

A TV Martel on inboard pylon with the ALQ-10 ECM pod outboard.

This was not to be the end of my association with Buccaneer flying. In 1994 I was serving with a Tornado squadron at RAF Lossiemouth (where it all started for me) at the time of the final Buccaneer squadron’s disbandment (208 Squadron). The boss of that outfit happened to be a friend of mine and I managed to talk him into giving me a trip for old time’s sake before it was too late. And so it was that I flew in a Buccaneer again on 15 February 1994, twenty-six years, eleven months and seven days after my first sortie. It certainly brought all those wonderful memories of the aircraft flooding back, and reinforced my belief that nothing else came close to engendering such a spirit among its aircrew – and what an aircraft.