Peter Kirkpatrick (right) with his pilot Giel van der Berg.

Peter Kirkpatrick (right) with his pilot Giel van der Berg.

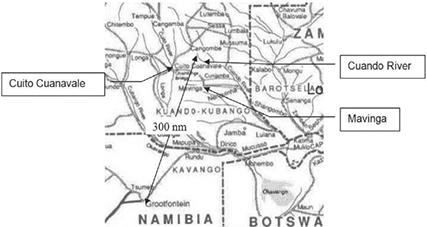

On my arrival at 24 Squadron in late 1985 the SAAF was at war again and the squadron was up at Grootfontein in Namibia. The MPLA (People’s movement for the Liberation of Angola) had started to push south east towards Mavinga in an attempt to defeat UNITA (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola) and the ‘Boere’ would have none of it. Army units and SAAF fighter and bomber squadrons were sent to the bush in support of UNITA. After a short sharp engagement that lasted a few weeks, the MPLA lost the heart for the fight and withdrew from the Mavinga area to avoid getting caught by the rainy season. The squadrons returned to their respective bases and were acutely aware that it was only a matter of time before they were back in the thick of the conflict.

By the end of 1985 there were in excess of 30,000 Cuban troops and 3,200 East German and Soviet advisors in Angola. In addition, the opposition’s air force could muster over 120 combat aircraft including thirty MIG 23 fighters equipped with AA-7 air-to-air missiles. The SAAF struggled to get more than sixty front-line aircraft together at this stage and these included the aged Canberra, Buccaneer and Mirage III.

General Konstantin Shaganovitch had been appointed as overall commander of all the MPLA forces. He was the most senior Soviet officer to command forces outside Europe and Afghanistan. This was a clear indication that the Soviets and Cubans were deadly serious about winning this conflict and confirmed that the USSR’s intentions for Southern Africa were very imperialist and not merely some benign benefactor supporting the oppressed African nations as some would like to have believed.

During 1986 the Soviets continued to pour in large quantities of ground equipment including T-55 main battle tanks and modern air defence systems including SA-8, SA-9, SA-13, and ZSU 23-4 radar-controlled guns. By 1986 Angola had 350 T-55 combat-ready main battle tanks, South Africa had thirty-two operational Oliphant (modernised Centurion) tanks.

In September 1987 Angolan forces (FAPLA) attacked UNITA in the south east of Angola. In response the South African Defence Force (SADF) mounted a counter offensive to help bolster the UNITA defence along the Lomba River where FAPLA had positioned four brigades, all defended by a formidable array of anti-aircraft missile and artillery systems.

As part of the effort to protect the UNITA forces, the SAAF committed five air defence and ground-attack squadrons including 24 Squadron’s Buccaneers.

By October 1987 the conflict had escalated into a full-blooded conventional war with tank battles ensuing in the bush. Most people do not realise that this was one of the major tank battles in Africa, post World War II, with FAPLA losing some 100 T54/55 main battle tanks in this conflict as the army pushed the enemy brigades back north west. Together with 1 Squadron’s Mirage F1-AZs, 24 Squadron had been carrying out daily strikes against the FAPLA ground forces. We were always aware of the threat from a SA-8 on the run-in to the target.

We were fitted with a very effective radar-warning receiver (RWR), which provided early warning and the aircraft had been modified to carry active jamming (ACS) pods designed to counter the various radar-guided SAMs, especially the SA-8. We also carried a full complement of chaff and flares. Chaff was deployed from prior to the pitch until we returned to low level after the attack. We would deploy the flares at the apex of the release to deal with the infra-red missiles. This is where I learnt that SA-7 and SA-9 love flares! Giel van der Berg and I were normally No.4 in the formation, which meant that we were always last off the target. It would always fascinate me to watch the multiple SA-7 tracking our aircraft and then going for the flares as soon as they were deployed. Thank the Lord that they always worked.

During this phase we were tasked to carry out a strike against a convoy that was re-supplying one of the retreating FAPLA brigades on 13 October 1987. This must have been about our tenth combat sortie so we were over our initial nervousness of operating in such a hostile environment (not that we were ever calm during an attack). We were flying in Buccaneer 422 and were No.3 of a three-ship and as we pitched up to commence the bomb release I noted that the RWR was making a lot more noise than usual. By the time we had commenced the break off, the RWR was screaming and the jamming pod was lit up like a Christmas tree. The SA-8 had locked on to us. It was directly in our six and I screamed at Giel to break. Like an idiot I omitted to tell him which way, which he immediately queried. My response was to get him to break downwards to low level and get the trees between the SA-8 radar’s line of sight and us. We were safely back at low level very quickly. Fortunately a combination of our attack profile, the chaff, the flares, RWR, jamming pod and some very hard manoeuvring allowed us to survive to fight another day.

Giel and I would normally chat on the way back (forty-five-minute transit at low level) after a strike. On that day we did not say too much to each other until we landed. We had both realised how lucky we had been to survive the sortie. We subsequently found out that some kind SAAF intelligence man had mis-plotted the position of the SA-8 to the north by some two miles. This meant that we had virtually pitched over it, which explained why it had managed to acquire the aircraft so early. Needless to say that particular intelligence officer was not very popular with the two of us.

One week later, on 20 October 1987, we had our opportunity to settle the score. We were tasked as part of a four-ship to go and destroy the SA-8, which was located on top of a ridge and was becoming a serious threat to operations in the area. We were flying in Buccaneer 414 and used the same initial point (IP) as the rest of the formation but separated from them on the run-in. We pitched, released our bombs and broke back to low level where I watched the string of ten MK 82s start to detonate (as air-burst) short of the ridge. The SA-8 was starting to go into acquisition and I could clearly hear it getting louder on the RWR audio. The stick continued to the top of the ridge and then the audio disappeared, a sure sign that the SA-8 was not working anymore. The ground forces confirmed a few days later that it had been destroyed. Not quite a HARM (high-speed anti-radar missile), but just as effective.

On 9 October 1987 Giel and I had been tasked to do a photo-recce sortie on the Cuito Cuanavale river bridge. The sortie was scheduled for 11 October during a busy time in the conflict when the Buccaneers flew fourteen strikes in a nine-day period.

The plan was to fly the sortie at the same time other Buccaneers, and some Mirage F 1s, were operating against FAPLA in the area between the Lomba River and SE of Cuito Cuanavale.

Given that operations were in full swing, and the Angolan MIG 23s were also operating over the whole of the area (see below), we were cautious with our planning.

Considering that most of south-eastern Angola was completely without friendly radar coverage at low level, we were well and truly in ‘indian’ territory. Fortunately we had plenty of fuel and were fitted with full chaff and flare as well as ACS pods.

I planned the run so that we could skirt the combat area by transiting to the east of Mavinga and running up the Cuando River, staying in the river valley and then approaching Cuito Cuanavale from the north east. This allowed us to use the terrain to remain masked from the radars at Cuito until the last minute, pitch for the photo run and then break off to the south at low level to return back to Grootfontein without transiting through the combat area.

On the 11th we took off in Bucc 416 at 0900 and headed to the east of mavinga to set up for the run. At the same time three other 24 Squadron Buccs were conducting strikes in the main combat area. The camera pack (a Vinten LOROP pod) was fitted in the bomb bay and was primarily used to take oblique photos at relatively low angles. This reduced the risk to the aircraft by not having to overfly the target and minimised the time the aircraft was exposed to missiles and fighters. The pilot used a graduated mechanical sight and roll control.

The initial transit was to the east of Rundu and we cruised at low level 100-200 feet AGL at 420 knots. While still over friendly territory we conducted our normal checks on the system. After rolling the bomb door open I conducted a check-out on the camera. Giel deployed the starboard sight for the camera and set up the sight angle to coincide with the camera setting. In this case the angle setting would have been about ten degrees to the starboard. Everything checked out, so we closed the bomb door and stowed the sight.

We accelerated to 480 knots, ‘descended’ to 100 feet and transited to the north and joined up with the Cuando River and turned north west. Having been used to over-flying many rivers in South Africa it really amazed me to see that this river was about four to five kilometres wide (in the flood plain) and, despite being the dry season, the actual river was twice the size of the Orange River in full flood (the Orange river is the largest river in South Africa). The Cuando is only one of a dozen similar-sized rivers in SE Angola.

Along the river we reached our IP and turned west to start our run-in. Although the Buccaneer was fitted with a good (for its day) navigation system, it was still effectively a dead reckoning system that required regular and accurate updates to ensure optimal performance.

We remained in the valley of the tributary and then accelerated to 580 knots at 100 feet. The RWR was still quiet. We hit the pitch point and Giel pulled at 5g and climbed to 10,000 feet, rolled inverted and pulled down at 5g to stop the rate of climb before rolling back to restore straight and level flight. By now we were at 12,900 feet (15,900 feet altitude) and Giel rolled the bomb door open. This manoeuvre took about thirty seconds, which was not bad for our old bus.

By now the RWR was very lively, with several SA-8s and SA-3s making themselves heard. The stand-off range from the target was seven miles, which kept us outside the range of most of the missiles in the Cuito area, but left us very exposed to any MIG 23s that were operating in the area. Once we were detected, the MIG 23s would have to be vectored to intercept us via the long-range search radars, which would take at least twenty seconds to establish a track on us once we had pitched from low level. By now the search radars were coming through loud and clear on the RWR. Although they did not pose a direct threat towards us, the clock was ticking and it was time to get the job done and back to the relative safety of low level as quickly as possible.

I switched on the camera and checked that it was running while Giel lined up the camera sight with the bridge. So far the sortie had worked out well. We had come through undetected and the bridge was where it should have been. The run was completed, I switched the camera off and Giel closed the bomb door and plunged back to low level using the barn doors (airbrake!) to get down fast. By now the RWR was screaming its head off with all the radar activity from Cuito and Menongue.

We hit low level at 580 knots and headed south, only to hear over the radio: “We are in your seven o’clock!” Giel and I gave the compulsory response of “huh?!?!” it took us about fifteen seconds to realise that we had heard Pikkie Siebrits talking to Mike Bowyer on their way out from their own strike to the south east of our position. That was a long fifteen seconds while we scanned the world around us for bogeys.

The rest of the journey was uneventful and we landed back at Grootfontein.

The film was removed for developing and analysis and we felt that this was a job well done, or so we thought.

Two days later, we got the message from Rundu that they were not happy at all with the photo run. Instead of the bridge lying in the lower third of the photo, it was two thirds up in the frame. Although usable, the intelligence people wanted better photos for later operations. After the usual ribbing by all parties, Giel and I were tasked to repeat the run, ‘mutter, mutter’. We triple checked the previous run and could not fault it at all.

On 14 October 1986, we climbed back into Bucc 416 and got airborne at 1,000 to repeat the exercise, determined to make up for the previous sortie.

After the system checkout before Rundu we were convinced that all was well, but could still not work out what went wrong on the previous sortie. As we passed north of Mavinga, Giel decided to check the camera sight again. It was then that he realised that the starboard graduated sight was in fact slightly loose and had vibrated itself to eight degrees instead of the ten initially selected. After some choice words he corrected the problem. The rest of the sortie was completed uneventfully apart from the RWR making a lot of noise as usual. This time the intelligence guys were happy with the photos and left us in peace without too many chirps.

By late October 1987 the FAPLA brigades were being pushed back from the Lomba River by the SADF and UNITA forces. The SADF wanted to create as large a buffer between Mavinga and Cuito as possible before the rainy season started and all fighting stopped. We were carrying out strikes virtually on a daily basis in support of the ground forces.

Our aircraft had been modified to carry eight MK 81s or MK 82s internally and eight MK 82s or twelve MK 81s externally. As an aside, we used to fly an air show routine with one ‘clean’ Bucc and one Bucc flying in this configuration doing some hard manoeuvring giving the message to the rest of the SAAF: ‘see if you can top this!’ Operationally these bombs could be conventional iron bombs or pre-fragmented bombs with up to 26,000 ball bearings and fused with airburst fuses. This inherently made the use of toss attacks a seriously viable option. The combined sticks from four aircraft would cover an effective area of one square kilometre.

To increase our chances of survival we made extensive use of toss bombing. We had modified the standard medium toss profile to release the bombs at a much higher angle (38-42 degrees). This increased the stand-off range at bomb release keeping us out of the SA-8’s range for long enough to carry out an attack and break off in reasonable safety.

24 Squadron low over the bush.

We had initially made sole use of the pre-fragmented MK 82 bombs with air-burst fuses. These were extremely effective on any troops that were exposed at the time of the strike, but were less effective against troops dug into foxholes. According to the intelligence reports, FAPLA learnt this lesson quite quickly. The pre-fragmented MK 82s were also very effective against trucks and light armour, especially radiators and tyres. Reports were being received of FAPLA resupply convoys coming from menongue and Cuito Cuanavale being heavily laden with replacement tyres and radiators. This reduced the space available for food and ammunition, which meant that the tactic was working.

At times a specific brigade would get bogged down and the SADF and UNITA ground forces would be battling to dislodge them. At these times we switched to conventional ‘iron’ MK 82 bombs with delay fuses. The time delay set would vary from two to forty-eight hours and we would toss up to forty-eight of these bombs into the area where a FAPLA brigade had dug in. These bombs would penetrate the soft ground and remain there until the delay times expired. This meant that we effectively mined the area with a bomb going off every hour for the next two days. After twenty-four hours the brigade would be so frazzled that they would up-sticks and continue withdrawing. The SADF troop could move into the area forty-eight hours after the strike, knowing that there would be no more bombs left to explode.

On 20 October 1987 Giel and I took part in a three-ship formation of Buccs on a strike south east of Cuito Cuanavale. The planned route was to approach along the Cuito River past Villa Nova del Armada, find the pre-IP navigation point, route to the east to get there, which was a strange shaped pan, and then turn to the north to the target. The break off was to starboard and to return to the south at low level. The reason for this was fourfold:

• The FAPLA brigade that we were attacking was defended by SA-9s and SA-8s spread out around the brigade. Army intelligence had reported that there was a defensive gap to the south and south east of the brigade.

• We were part of a combined strike with a formation of four Mirage F1-AZs attacking from the south east thirty seconds before our intended strike time.

• We were getting too close to Cuito Cuanavale to risk approaching from the north.

• The pan to the south of the target was the only usable IP in the area.

We were airborne at 1520 in Buccaneer 422 and as usual, Giel and I were No.3 in the formation. As mentioned previously it was critical to keep the navigation system accurately updated but this was not easy in wide battle formation 3,000-6,000 feet on the beam of the lead aircraft. Giel and I had developed a technique of lagging the lead pair during the crossover in formation to ensure that we positioned ourselves over the fix point to ensure an accurate update of the navigation system. This was especially important just before the IP, particularly when it was a pan in the middle of an otherwise featureless area and we were flying at 480 knots at 100 feet.

As we came up to the navigation fix point on the river, we were expecting to turn eighty degrees to the right and as usual we ensured that the navigation system was accurately updated in the crossover in formation.

The lead aircraft turned thirty degrees right and no further. We were now heading directly for the target, via the SA-8 defences, with the IP moving to the right and mirages still in the area.

Keeping in mind that we always operated in full radio silence (particularly before the attack), I immediately told Giel that we were heading for a disaster. He concurred and agreed that I break radio silence. I called the lead navigator and politely asked if he needed help and indicated that the IP was sixty degrees to starboard. It is important to note that we were moving off track very quickly at eight miles a minute.

Cmdt Lappies Labuschagné (OC 24 Squadron) was the formation leader and realised that things were going horribly wrong. We either had to correct matters quickly or return home. He told us to take over formation leadership. I called a 270 degree turn left to close in on the IP from the west.

I must admit that my heart was in my mouth because I realised that if I was wrong, I would never live it down. Thanks to the accurate navigation system update prior to the IP we ended up right on top (albeit forty seconds late) and marked it, starting the weapons system run in to the pitch point. We turned hard left to the target and went ‘buster’ (full power) accelerating to 540 knots with the rest of the formation lined up behind us for the attack.

Giel rolled the bomb door open and I started the chaff running just before the pitch. By now the RWR confirmed that the SA-8s were indeed to our left which agreed with the intelligence reports. Giel was now flying the aircraft using the weapons system commands in the HUD (head-up display) and we were flying at about eighty feet and 550 knots. The beauty of a two-man crew in these conditions is that the pilot just has to worry about flying the aircraft and the navigator sorts out the weapons system, arming, chaff, flares, active jammer and look-out. We hit the pitch point at 4.7 miles from the target and Giel followed the commands in the HUD pulling up at 4g. After six seconds the bombs released automatically in sequence at a pitch angle of about thirty-five degrees. We felt the ‘thump’ of the ERUs (ejector release units) ejecting the bombs from the aircraft. Once the bombs were all released Giel commenced the escape manoeuvre hard right as I visually confirmed that the bombs were released and started the release of the flares to deal with any infra-red missiles. By now the chirp of the SA-8 was becoming very loud, but it had not locked on for launch yet. Thirty seconds after the pitch-up we were back in the relative safety of low level and 580 knots heading south. At this stage it was the navigator’s job to check the tail was clear from missiles and other bogeys. We would also try to assess if the bombs were on target – not easy in such featureless terrain and at six miles range.

It always amazed me how well the Buccaneer handled under those conditions. The aircraft had a reputation of turning like a brick. This was true at 500 knots, but was not true at 380 knots, which was the typical speed at the top of the apex after weapon release for toss bombing. At this speed the pilots could safely turn the aircraft at 5g without risking a nasty flick-in that the aircraft had a reputation for doing. The pilots on the squadron actually made use of the onset of buffet (the buffet occurs when the aircraft is approaching the stall and is very predictable if you know what to look for) to be able to control the aircraft during these conditions.

A testimony to the handling of the aircraft was that no Buccaneers were lost during these operations in Angola. Once or twice we ended up (inadvertently) in the same airspace as the Mirages when we struck the same brigade and from similar directions due to operational limitations. In this case the timing of the strikes was only separated by thirty seconds to avoid giving early earning to FAPLA. If the timing was slightly out by one or both parties we could end up pitching simultaneously. The Mirages would pitch from six miles and we would pitch from four-and-a-half, giving us some separation, although as far as I could remember this only occurred twice in the campaign. During one such case Mike Bowyer ended up in formation with a Mirage at the apex of the escape manoeuvre.

It also helped enormously that the Bucc pilots did not have to worry about anything other than flying. In contrast the poor F1-AZ pilot was very busy in his office at this stage of the sortie. With very few of the onboard systems being integrated, he had a massive workload. I can still clearly remember one of the F1-AZ pilots (Reg van Eeden) telling a story of how he nearly flew into the ground during an escape manoeuvre. During the early phase of the operations the Bucc navigators were continually reporting on the amount of SAM and AAA activity at the debriefings and some of the F1-AZ pilots were sceptical about our reporting, due to the fact that they had not seen as much activity as we had. By their own admission, however, the F1-AZ pilots agreed that they really did not have much time to look around. After flying about five strikes, Reg felt that he could sneak a peek at the RWR during the escape manoeuvre. In his own words, he nearly ‘cr***ed himself’ when he saw the number of SA-8s on the RWR as he took a handful of stick to get back to low level ASAP. In the process he ended up heading for the ground in a near vertical dive and only just managed to stop himself from becoming a permanent feature of the Lomba River landscape. When he returned from the flight he was really shaken up by what he had seen and what he nearly did to himself. His account made me even more thankful for the fact that I was operating in a two-man crew with a good weapons system and a damn good EW system.

The operation lasted from September 1987 until April 1988. The Mirage F1-AZs flew over 1,000 combat sorties in this period (with just ten aircraft) and the Buccaneers flew 150 combat sorties (with just four aircraft). All of these sorties were into areas that were heavily defended and we were always met with a barrage of anti-aircraft fire and missiles. On several occasions 1 Squadron did run into a few MIG 23s at low level but, for most of the time, the Cuban pilots were loath to operate outside radar coverage. Amazingly, during this period only one ground-attack aircraft, a mirage F1-AZ, was lost to enemy fire.

Our extremely low loss rate was due to a number of factors. Excellent passive and active ECM kit, tossing bombs from a few miles out and the aircraft’s outstanding performance at very low level when it was quite normal for us to fly at 540 knots at eighty feet on the run-in to a target – the only place to be in a Buccaneer.