CHAPTER 4

Displaying the Stone

A suiseki that is poorly displayed loses much of its beauty and suggestive power. As a result, collectors take great care in choosing an appropriate container and in creating a beautiful display area. Reflecting these areas of concern, this chapter is divided into two parts. The first part describes different types of suiseki containers, while the second discusses the creation of a display area.

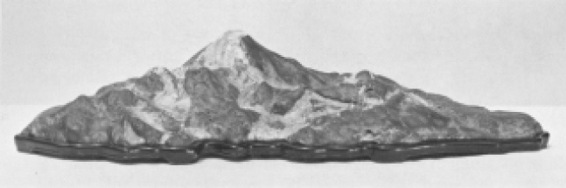

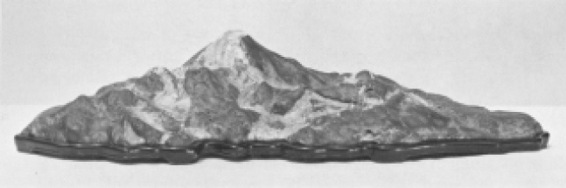

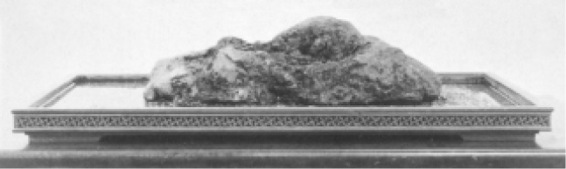

Aside from placing a suiseki in a tray containing plants and other materials (a practice to be discussed in Chapter 5), there are two traditional ways of exhibiting a suiseki: on a dai (sometimes referred to as a seki-dai), a wooden base carved to fit the stone; or in a suiban, a shallow watertight container filled with sand, water, or both (Fig. 65). Some collectors will exhibit the same suiseki in a suiban in summer to suggest coolness, and on a dai in winter. In either instance the container should not detract from the stone; the suiseki always takes precedence over the container.

A dai is traditionally dark in color. The wood either has a natural finish or it is covered with black, brown, reddish-brown, or clear lacquer. Carved to follow the exact lines of the stone, a typical dai has a narrow lip and short legs. If the base of the stone is irregular or uneven, the interior of the dai is often carved out until the stone can be firmly seated. Appendix I (p. 142) provides a detailed description of the carving process, as well as a description of the woods, styles, dimensions, and finishes used.

Fig. 65. (a) Distant mountain stone set on a dai. (b) Same stone set in a bronze suiban.

Suiban come in a variety of colors. Most suiseki collectors prefer suiban that are pastel or neutral in color (especially shades of gray, beige, or tan), since these shades are less likely to detract from the color of the suiseki. If a brightly colored suiban is used, it should complement, not compete with, the color of the suiseki. A bright red suiban, for example, would not be appropriate for a predominantly red-colored stone.

Traditionally, suiban have short squat legs, are rectangular or oval in shape, and are made of glazed or unglazed earthenware or ceramic. For exhibiting fine or delicate suiseki, some collectors use a watertight bronze or copper tray (known technically as a doban) that has been allowed to develop a gray-green patina. In areas where suiban are not commercially available, shallow oval or rectangular bonsai trays are often suitable, especially if the drainage holes are plugged with a waterproof compound.

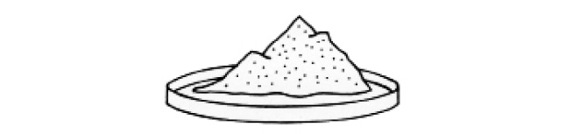

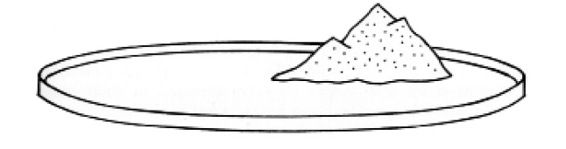

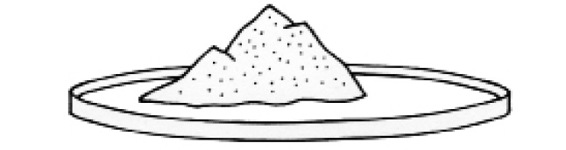

Suiban vary widely in length and width, although they are typically 16 to 18 inches long and 10 to 13 inches wide. On average, a typical suiban is twice the length of the suiseki (Fig. 66). If the suiban is too long or wide for the stone, some collectors will fill the excess space with a miniature accessory, such as a cottage, sailboat, or human figurine.

(a) Poor choice: suiban too small for suiseki

(b) Poor choice: suiban too large for suiseki

(c) Good choice: suiban approximately twice the size of suiseki

66. Relationship between size of suiban and suiseki.

The depth of a suiban ranges between ½ inch and 1½ inches. The average ratio of the height of the suiban to the height of the suiseki is about 1:4 or 1:5, with the ratio for different displays varying between 1:2 and 1:7. In general, suiban for flat, smooth, or delicate suiseki tend to be shallower than suiban for rough, heavy, massive, or tall suiseki.

Aside from the suiban’s color, height, and length, the style and shape of the lips, legs, and sides also need to be considered. Different styles and shapes vary considerably in their visual impact, and this must be taken into account in choosing a suiban (Figs. 67-70). Visually powerful suiban are generally appropriate only for visually powerful suiseki.

Fig 67. A shallow, oval-shaped ceramic suiban with straight sides and simple lines, suitable for a smooth and delicate suiseki.

An example of a powerful suiseki would be a rugged and massive Near-view mountain stone with rough textures and forceful lines. A visually powerful suiban would have one or more of the following characteristics: wide and flaring lips; decorated side panels (with the design inset or in relief); squared-off corners; straight, highly convex, or highly concave sides; substantial depth; and complex or heavy legs. A soft and delicate suiseki, with smooth textures and rounded lines, would probably be overwhelmed by such a suiban. A more appropriate suiban would be one that is shallow and oval in shape, with a narrow lip or no lip at all, with plain, slightly convex or slightly concave sides, and with plain or inconspicuous legs. If there is any doubt about the visual impact of the suiseki, it is usually best to choose a simple, unadorned suiban.

The suiban is traditionally filled with sand and water. Most collectors level and smooth the sand using feathers, spoons, or other tools. Alternatively, the sand can be smoothed by (1) filling the suiban with sand and water, (2) shaking the suiban back and forth until the sand is flat, and (3) removing the excess water by carefully tilting the suiban. Fresh water can then be poured into the suiban from behind the suiseki. When the stone is exhibited, the height of the water above the level of the sand should be approximately ¼ inch (Fig. 71).

Most collectors use only off-white or beige sand, as pure white sand is considered too bright (see Fig. 64). Sands of different levels of fineness are used, ranging between screen-mesh 24 and 14 lines per inch. The sand is always carefully sieved and washed before display. Fine-grained sand is generally employed with smoother or smaller suiseki, while more coarsely grained sand is used with roughly textured or larger suiseki. These are only crude guidelines, however, and the exact color and texture of the sand will depend on what best complements the stone.

Fig. 68. A shallow, oval-shaped ceramic suiban with straight sides and a heavy rim, suitable for a heavy stone with both rough and smooth surfaces.

Fig. 69. A shallow, oval-shaped bronze suiban with straight sides and silver-inlaid panels, suitable for a suiseki with rough texture or complex surface patterns.

Fig. 70. A deep, rectangular-shaped ceramic suiban with straight sides and thick walls, suitable for a rugged and powerful suiseki.

Fig. 71. Distant mountain stone set in a bronze suiban filled with sand and water. The elaborate design of the suiban harmonizes well with the rough texture of the stone.

Fig. 72. Thatched-hut stone set in soil covered with moss and short grasses. The off-center placement of the stone is most appropriate.

Occasionally, a suiseki collector will omit the sand, filling the suiban with water only, especially if the bottom of the suiban is beautifully glazed (see Fig. 20). Even more rarely, some collectors will set the suiseki in a bed of soil covered with a blanket of moss or short grasses (Fig. 72). If soil is used, the suiban should have water-drainage holes; without these holes, the soil will become waterlogged.

In recent years the practice of using only sand in the suiban has substantially increased in popularity (Figs. 105, 106). However, many traditionalists criticize this trend, arguing that the full power of a suiseki can only be brought out by placing the stone in a water setting. Apart from the symbolic importance of water (as a nourishing and restorative substance), its fluidity, softness, wetness, and reflective qualities effectively balance the solidity, hardness, and dryness of the stone.

The proper positioning of the suiseki in the suiban is of great importance. The stone should appear to be anchored or deeply buried,

Fig. 73. Weak stone placement: the suiseki is apparently floating on the sand in the suiban; the stone should be buried more deeply.

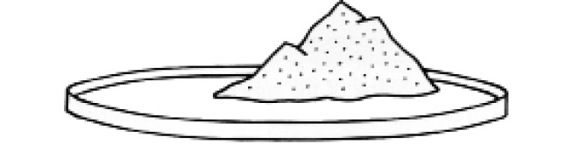

not floating or sitting on the surface (Fig. 73). The stone should also be set off-center and slightly behind an imaginary horizontal line running through the middle of the suiban. Although no absolute rules have been established—the exercise of good aesthetic judgment being the dominant factor—the center of the suiseki is typically placed about sixty percent of the distance from either the left or right side of the suiban, with ample room left between the stone and all edges of the container (see Fig. 66). If the stone is angled to the right or if the highest peak is on the left side, the stone is placed on the left side of the suiban (the open space at the opposite side of the basin is sometimes referred to as an “eye-resting area”). Conversely, if the stone is angled to the left or if the highest peak is on the right side, the stone is placed on the right side of the suiban (Fig. 74). Whatever the final placement, most suiseki are tilted slightly forward in the direction of the viewer.

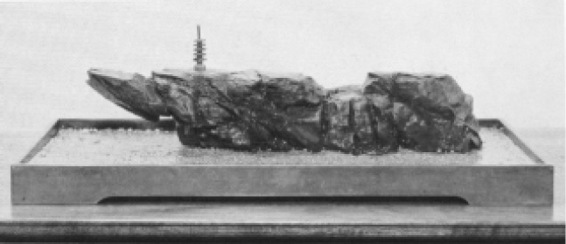

Miniature accessories—such as miniature houses, boats, bridges, animals, or human figurines—are seldom used with a suiseki. Such accessories are frequently out of scale with the scene suggested by the stone. Morover, they can limit the suggestive possibilities of the suiseki. A miniature boat placed in a suiban containing sand and a Mountain stone, for instance, forces the viewer to see an island; without such an addition, some viewers may see a mountain thrusting its summit through a thick layer of clouds or a peak rising above a field of ice. This does not mean that miniature accessories should never be used. However, they should be placed as inconspicuously as possible and used primarily to accent or emphasize strong points of the suiseki. Also, they should be in scale, they should be of the finest workmanship and quality (some of the best being made of bronze or copper), and they should be employed with great discretion. If care is exercised, a well-chosen miniature accessory can heighten the viewer’s appreciation of the suiseki (Figs. 75, 107).

(a) Weak placement: left side of suiban

(b) Weak placement: center of suiban

(c) Good placement: right side of suiban

74. Placement in the suiban of a stone whose right side is higher than its left.

Fig. 75. Island stone with a finely crafted bronze miniature pagoda enhancing the atmosphere of the display.

The display alcove

When exhibited in a Japanese style display area, a suiseki is almost always accompanied by another work of art, such as a bonsai, a Japanese flower arrangement, a fine ceramic or lacquer piece, a planter containing grasses, an incense burner, or a hanging scroll. These objects are traditionally placed in a tokonoma—a recessed alcove 3 feet deep, 6 to 9 feet long, and approximately 4 inches above floor level. The surface of the tokonoma is covered either with polished wood or with a tatami, a mat made of rice straw and woven reeds. When displayed in the tokonoma, each individual object is typically placed on a wooden table or stand with its most attractive side facing toward the viewer (Figs. 76-78).

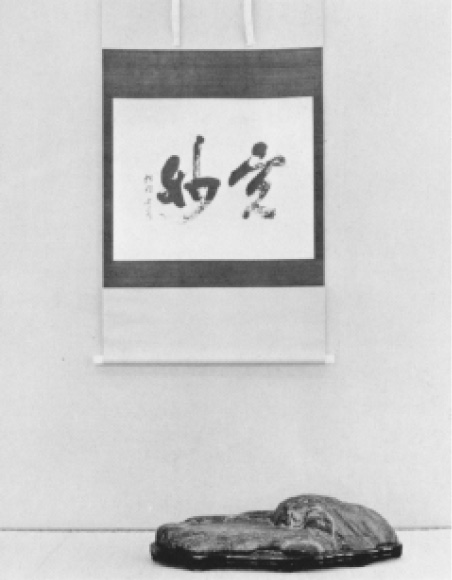

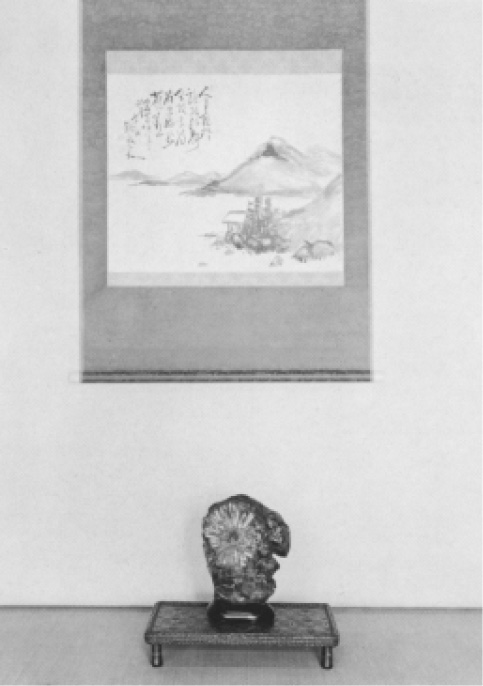

On the back wall of the tokonoma, a hanging scroll is traditionally hung in the exact center, with the principal display piece directly in front or to the side of the scroll. The subject of the scroll is usually a poem written in Japanese calligraphy or a landscape painting that is closely related to the suiseki and the other objects on display. The scroll and art objects should complement, not duplicate, one another. When viewed as a group, the objects should form a simple, serene, and harmonious whole, suitable to the season in which the objects are displayed.

Many Western collectors substitute a photograph, drawing, or print for the traditional Japanese scroll. In recent years some collectors have also experimented with incense, soft music, and colored lighting to enhance the suggestive atmosphere.

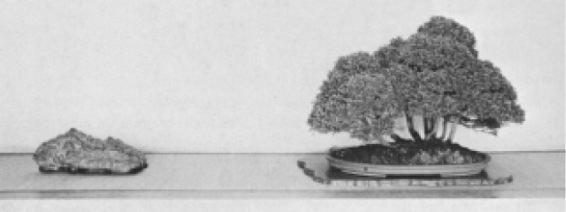

Fig. 76. Distant mountain stone displayed with an Ezo spruce bonsai and a planter containing ferns. The placement of the art objects is excellent; each one occupies one point of a balanced asymmetrical triangle.

In Western style rooms containing Western style furniture, a display area can be created on shelves or on a table set in a corner. The height of the display area is usually at least 2 feet above the floor. A plain off-white or beige wall is the most effective background, although an unpatterned off-white, beige, gray, gold, or silver curtain or flat screen can also be used. Lighting should come from above and in front, so as not to cast shadows.

Tables and other types of stands

The most attractive tables are made of polished teak, rosewood, or other fine wood, with legs that are either straight or curved (Fig. 79). The exact height of the table is determined by the art object’s height and shape. Mountain and Waterfall stones, as well as objects that have a strong vertical orientation, generally look best on medium-high or high tables. Plateau and Slope stones, as well as objects that have a strong diagonal orientation (such as slanting style bonsai), generally look best on low to medium-high tables. Shore, Island, Coastal rock,

Fig. 77. Distant mountain stone displayed with a hanging scroll in a tokonoma. The placement of the suiseki in the exact center of the tokonoma creates a formal atmosphere.

Fig. 78 Distant mountain stone, set on a low table, used with a Japanese chrysanthemum flower-arrangement and two hanging scrolls in the interior design of a Japanese style room. The bamboo outside the window suggests a bamboo grove and forms an interesting background for the suiseki.

Fig. 79. Various stands used for displaying suiseki and other art objects.

and Waterpool stones, as well as objects that have a strong horizontal orientation, generally look best on low tables. As a rule of thumb, the table is seldom greater than one and a half times the height of the subject. For stability, however, exceptionally tall suiseki tend to be set on low tables.

The shape of the table—oval, rectangular, or irregular—should be closely related to the shape of the art object and its container. Similarly, the visual power of the table, determined by its visual heaviness and by the complexity of its design, should be in harmony with the visual power of the object. For example, a heavy and rugged object—such as a Near-view mountain stone—set in a heavy rectangular container might suitably be placed on a visually powerful rectangular table. As a general principle, the greater the visual impact of the art object, the heavier the feeling of the table and the thicker the wood and legs (Fig. 80).

In all cases, 2 to 4 inches of space should be left between the container and the edges of the table. To protect the finish of the table, a piece of glass, a sheet of clear plastic, or a neutral-colored pad, mat, or cloth is often placed between the container and the table.

Fig. 80. A rugged Mountain stone set on a sturdy rectangular table. Since the suiseki is the focal point of the display, it is raised higher than the companion piece, a five-needle pine bonsai. The suggestion of alpine scenery is enhanced by the bonsai—a high-altitude species—and by the higher placement of the stone.

In addition to tables, collectors use a variety of other types of stands to display suiseki, including polished tree stumps (with flat tops and with gnarled roots for legs), rectangular boards (either lacquered or well seasoned), stone slabs, rafts made of bamboo canes or reeds (tied together with raffia or hemp cord), and natural or carved wooden boards made of polished tree burl or driftwood. Some collectors prefer the simplicity of a flat cherry, pine, or hemlock board, ½ to 1 inch thick, that has been lightly burnt with a torch, washed and scrubbed with a wire brush, and then painted with clear lacquer. However, the stand should never detract from the suiseki or its container; the suiseki always takes precedence over the stand (Fig. 81).

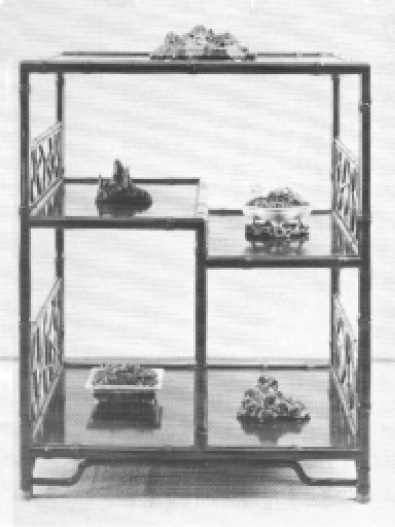

Miniature suiseki and art objects less than 3 inches tall require special stands. The objects are usually arranged as a group and are displayed on stands with tiered or staggered shelves (Fig. 82). The location of objects on each shelf should be consistent with their location in a natural environment. As a result, Waterpool, Island, Coastal rock, Shore, and Thatched-hut stones, as well as bonsai common to lowland areas and planters containing grasses, are generally placed on the lower shelves; whereas Distant mountain stones and bonsai trees commonly found in upland areas are generally placed on the upper shelves.

Fig. 81. Poor choices of stands: (a) The suiseki is overpowered by the heavy, elaborate table. A simple and sturdy table one-third the height of the one used would be more refined, (b) The same suiseki is in this instance overpowered by a thick board made of polished tree burl. A board one-third the height would be more complementary.

Designing and arranging the display area

The creation of a beautiful display area requires considerable thought and attention. It is essential that one object be clearly identifiable as the focal point or principal subject of the display (Fig. 83). The subject and shape of the companion pieces should be chosen to complement and enhance the principal object. Emphasis can be added by placing the principal object on a higher stand (Fig. 84). Other objects can also be placed on stands, but these should be lower in height. To further enhance the beauty of the principal object, the total number of objects on display should be kept to a minimum. Displays that include more than three objects often appear cluttered.

Fig. 82. Arrangement of miniature suiseki and planters on a stand with staggered shelves.

The color of the stands, containers, and companion pieces should complement the principal object. A dark purple suiseki, for example, will often be displayed with art objects, containers, and stands that are green, red, yellow, black, gray-brown, or neutral in color. Interest is added to the display by selecting objects that do not exactly repeat the same colors. The arrangement can also be enhanced by varying the texture, shape, size, and height of all objects set in the display area. A smooth-textured suiseki, for instance, might look best placed next to a finely detailed art object. The slant of the objects, the distance between them, and the shape of the stands should also vary.

A generous amount of space should be left between the edge of the tokonoma or display area and the objects. Sufficient space should also be left between the objects themselves, and between the bottom of the scroll and the top of the art objects. With one exception, the principal object of the display is traditionally placed off-center, approximately one-third the distance from the edge of the display area, and slightly behind an imaginary horizontal line running through the middle of the space (Fig. 85). The exception occurs when the principal subject is particularly stable in appearance, when it conveys almost no sense of horizontal movement, or when the intention is to emphasize its beauty. In such cases the object is placed in the center of the display area with the hanging scroll set directly behind it (Fig. 86; see Fig. 77). If two objects are set in the display area, one should be set back from the other; they should not be arranged in a line parallel to the edge of the display area. If three objects are placed in the display area, they should be arranged to form an asymmetrical triangle (from both an aerial and frontal view). When viewed from the front, the terminal or highest point of each object should form one corner of the triangle, with the highest point of the principal subject elevated to form the peak of true triangle. The top of the scroll, the edge of a stand, or the edge of the display area can also function as one corner of the triangle.

Fig. 83. A poorly designed display area. The Shelter stone, incense container, and hanging scroll each compete with one another for attention; none is clearly identifiable as the focal point of the display.

Fig. 84. A weak display. The Mountain stone and Ezo spruce, set at the same level, compete for attention. The display could be refined by placing the suiseki on a low table.

Fig. 85. Plateau stone with a hanging scroll in a tokonoma. The design of the display area is simple and elegant. Since the high point of the suiseki is on the right, the stone is placed to the right, approximately one-third the distance from the edge of the alcove.

Fig. 86. Neodani chrysanthemum-pattern stone with a hanging scroll in a tokonoma. The stone conveys almost no sense of horizontal movement and is thus placed in the exact center of the display area. The suiseki and the subject of the scroll, a small house built on the shore of a mountain lake, beautifully complement one another.

Combining art objects

A major consideration in combining art objects is the degree of intended formality. Three levels of formality are traditionally distinguished by Japanese collectors: formal (shin), semiformal (gyo), and informal (so). The formal style of display is characterized by the greatest verticality, symmetry, straightness of line, and decorum. As a result, the classic suiseki—the Distant mountain stone—is best suited for formal style displays. Since the concept of formality also encompasses the containers, stands, and other objects in the display area, the emphasis should also be on verticality, symmetry, straightness of line, and subdued or neutral colors (see Figs. 77, 86). Antique Chinese containers and stands have traditionally been considered appropriate for formal displays.

The semiformal style of display is characterized by greater horizontality, asymmetry, softness of line, and curvacious form. Appropriate suiseki for this style are Slope and Plateau stones. For semiformal displays, art objects with soft contours and slanted or curved lines, as well as rounded or oval containers and stands, are preferred (see Fig. 85).

The informal style of display is characterized by the greatest horizontality, asymmetry, irregularity, flexibility, casualness, delicacy, and softness. Suiseki most suited to this style are Waterpool, Thatched-hut, Pattern, and softly contoured Slope or Distant mountain stones, especially when set next to a planter containing sweet rush (sweet flag or acorus), dwarf pampas-grass, dwarf bamboo, or other grasses (see Fig. 108). Suiseki that are humorous or playful are also appropriate. For informal displays, the art objects, containers, and stands can be elaborate and colorful or quite simple.

Season

When selecting objects for the display area, it is customary to consider the symbolic and seasonal significance of the objects (Fig. 108). In winter, and especially during the New Year holidays, the Japanese traditionally display objects that symbolize or represent the “three friends of winter”—pine, bamboo, and Japanese plum blossoms. The pine, green all year and clinging with all its power to a rock face or cliff, symbolizes long life. The bamboo, because of its flexibility and its ability to bend without breaking, symbolizes strength and endurance. Japanese plum blossoms, which appear when the ground is still covered with snow, symbolize courage and nobility. These three items, when represented by a Pattern, Object, or Color stone combined with a scroll or the plants themselves, convey the host’s wishes for good fortune in the new year.

In the spring, summer, and autumn, the following subjects are especially popular in Japan: Japanese plum blossoms, wisteria, forsythia, and cherry blossoms in early spring; azalea, iris, and peony in late spring; lotus, bush clover, pomegranate, weeping willow, morning glory, green grasses, waterfalls, and mountain lakes in summer; chrysanthemum, persimmon, red maple leaves, berries, flowering pampas-grass, and the harvest moon in autumn.

Harmony of the overall design

Figure 108 illustrates how some of the factors described above are applied in practice. In this sparse and deceptively simple asymmetrical arrangement of only two subjects, the focal point is a Distant mountain stone. Each element in the arrangement reinforces and enhances the seasonal theme of the display: a peaceful summer day in the country. The planter containing grasses in the foreground set on a flat, thin, irregularly shaped piece of wood suggests the green fields of summer; the suiban filled with water and sand suggests a cool mountain lake; the high table in the background heightens the illusion of a high distant mountain; the yellow color of the suiban recalls the warm colors of summer; and the simple, smooth, soft, and rounded lines of the containers, stands, and art objects heighten the sense of calm and tranquillity.