SHAME AND GUILT—WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE?

Can we ever leave our reactive baggage behind? Yes. It will require work, but time is our friend. The first step in the process is to understand the difference between shame and guilt.

If I don’t know the difference between shame and guilt, I will never be able to find and understand my value as a person. Shame is the perception that locks me into a belief system that says, “I’m bad. I’m wrong. I’m no good.” It comes out of a tendency toward perfectionism and leads to the expectation of rejection, rigidity, isolation, and despair. When I operate from a shame-based worldview, my value is buried under my dysfunctions, fears, anxieties, behaviors, mistakes, imperfections, rejections, feelings, powerlessness, and sins. I am satisfied with nothing less than perfection. I live on a performance basis and place unrealistic expectations on my partner and those around me as well as myself. No matter what I do, I feel I’m never good enough.

Shame and rage are interactive—where there is rage there is shame. Rage comes from helplessness. It hides shame. Rage keeps a person from being exposed. It is isolating and disconnecting.

Anger, which is not the same as rage, is a way of expressing feelings in order to connect and repair the relationship with another person.

Shame is a learned behavior. We weren’t born with it. Rather, we learn it from various sources, such as our family of origin, school, relationships, culture, and even church.

Guilt, on the other hand, can be a healthful emotion that a person with a strong value system experiences. It is based on a presumption that says, I made a mistake. I did a bad thing. My attitude or behavior was wrong, or I have sinned. But I am a person of worth and infinite value. When my core value is in place, I have the ability to change my attitudes, behaviors, reactions, and actions. In other words, I’m in control of myself. When I function in a guilt-based system (as opposed to a shame-based system), I grow in accountability and responsibility. My self-worth deepens, and my character is formed. I can build a healthy belief system on a firm foundation. My mistakes and failures become learning experiences. They do not reflect my self-worth. I have the power of choice to change attitudes and behaviors.

Guilt can be atoned for because the promise of love is still there and we can experience the relief of being forgiven. It has a beginning and a possible ending. Guilt is about your behavior. Shame is about you. Guilt can be a learning tool, but shame blocks learning. Shame and blame go together and can be aimed at self or at others.

The shame produced by the wounds of childhood can be processed to guilt, just as the caterpillar becomes a butterfly. Discovering the sources of our shame is the beginning of that transformation.

GUILT IS ABOUT YOUR BEHAVIOR. SHAME IS ABOUT YOU.

The shame-based person fears punishment, abandonment, and rejection. He or she feels overly responsible for circumstances. Shame is the byproduct of the way a person is treated. I was treated as though I were worthless; therefore I must be worthless might be the thought. Part of the healing process is to recognize the shame as a truth of the past but not as a truth about the person today. We live in a shame-based society. The shame produced by the wounds of childhood can be processed to guilt, just as the caterpillar becomes a butterfly. Discovering the sources of our shame is the beginning of that transformation. Consider the following steps that can start you on your journey to freedom:

• Identify the wounds of childhood—almost everyone has something in childhood that hurts. It can range from minor things on the surface to major deep pain or wounds. We can’t always remember them clearly. If the memory has faded, don’t go digging into the past. The memories will surface when you’re ready and able to process them.

• Identify the reactive behaviors that undermine our values and perpetuate the shame. We can tell by our reactive behaviors if there’s been a wound in childhood. We may have lost the memory consciously, but the wound will unconsciously drive our behavior. I started recovery without the memories coming to the surface by identifying the behaviors and changing them. It is a process.

• Recognize that with the shame there comes pain. This is normal. Journal or log the feelings you’ve associated with each incident. Stay with the process. The pain will eventually diminish, and you’ll see light at the end of the tunnel.

• If the pain or the fear associated with the incidents is too much to handle, get help. A trusted friend, family member, or your pastor may or may not be the place to start. There should be no shame in seeking professional help.

• Focus on growth, which develops maturity of character. If we are arrested in our development, we have never developed our core and character. Our personality is a pseudopersonality, and much behavior modification will not work long-term. As we focus on the development of character, we grow from the inside, and behavior changes over time. Then the change can be permanent.

• Become future-oriented instead of dwelling on the past. Choose to live in the solution instead of perpetuating the problem. Look forward. As we mature we can take control of our lives and let go of situations, circumstances, and other people. We can achieve our dreams, goals, and visions.

• Determine to do everything you can to stop the behaviors connected to the wound. When we identify a negative behavior, look for the opposite behavior and focus on change. Do not try to change everything at once. Time is our friend. It took many of us years to get this way, and the recovery process might take the rest of our lives. But it does get progressively better.

Continue to grow over the long term by using positive, self-valuing statements, finding a support system, and focusing on spiritual growth.

For the batterer, containment (taking responsibility and initiative to stop the behavior) is primary. This is true for the emotional abuser as well as the physical abuser. For the victim, safety is primary (removing herself from the situation using the resources of the community such as marital separation and counsel, shelter, order of protection, law enforcement).

If you are a woman caught in emotional abuse, there’s another way out: as you discover your value, you’re empowered to make decisions and take healthy control of your life. You’re free to discover the person God has created you to be. The healing process has begun.

THE ANGER KIT

After we’ve discovered the source of our shame, we can expect two responses: pain and anger. Our individual anger pattern as an adult is usually a refinement of the anger patterns we learned in childhood. If Dad screamed and threw things when he was displeased, that will be my mode. His model gives me permission to act out in his way. It seems to work. My wife and children skitter around to obey my every command and fix my problems when I raise my voice. I am in control.

Even if I determine to reject my father’s model, I have to unlearn and reshape my anger response. Otherwise, it will manifest itself in other areas, such as control, manipulation, rigidity, or avoiding the conflict altogether. When I get mad, I may not throw things and yell—I give my family the cold shoulder and the silent treatment instead. My wife and children work harder to please me and fix my problems. I am in control. And despite my determination not to be like him, I have embraced my father’s anger model without even knowing it.

For insight into our emotional reactions, it is best to look at least two generations back into the family of origin. Understanding how your parents and grandparents acted out their anger can give you a clue to your own responses.

Understanding Anger Patterns in Your Family of Origin

1. How did your parents act out their anger?

2. How did your parents react to each other’s anger?

3. How did your grandparents act out their anger?

4. How did your grandparents react to each other’s anger?

5. How did your parents handle conflict—was it resolved or avoided?

6. Were you afraid during your parents’ expressions of anger?

7. Were you allowed to express anger as a child?

8. How did you express anger as a child?

9. How do you express anger now?

10. If you could, how would you change your responses to your anger?

Our individual anger patterns as adults are usually merely fluffed-up versions of our childhood anger patterns (learned behavior). They are fairly “set” or “fixed.” As a result, they are also predictable. People who know us well know just the right “buttons” to push to get the anger responses they wish to provoke.

However, because these patterns were learned, they can be unlearned and reshaped. We can decide what we want our pattern to be by adjusting our expectations and responses.

Anger is a universal, basic, normal, unavoidable reaction of displeasure. It usually involves a significant portion of misunderstanding and has its roots in our own unmet expectations. It generates an internally created, increased physical force that we control or fail to control as we choose.

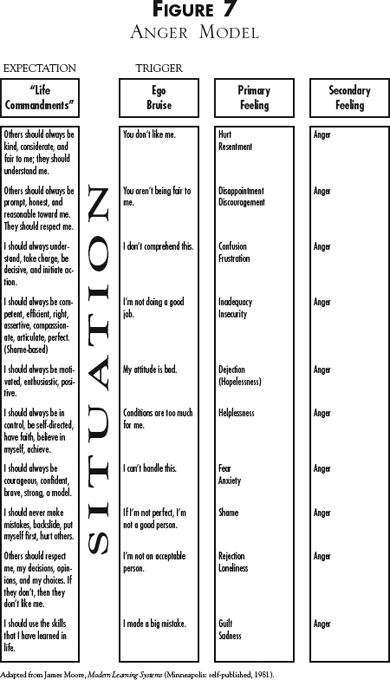

Anger is a secondary emotion; more basic emotions underlie it. It entails contradiction of a belief or self-concept. Our anger responses are patterned and programmed; we were taught by example how to respond. Because responses are internally created, they can be internally managed. They are most often expressed toward those who are meaningful to us.

Anger is an emotional reaction to certain kinds of stress-producing situations. Anger is not a primary emotion, but is rather a secondary reactive response. More basic emotions underlie it, such as in the Anger Model (see Figure 7).

Anger is a universal, basic, normal, unavoidable reaction of displeasure. It usually involves a significant portion of misunderstanding and has its roots in our own unmet expectations.

When we become angry, we react impulsively. Without delayed responses or impulse control, we will trigger and go directly to our learned reactive behavior, which is generally aggression. Anger and aggression are different in that while aggression is intended to cause injury or harm, anger gives us strength, determination, and sometimes satisfaction. It has desirable as well as undesirable effects. Our purpose is to decrease the negative effects and increase the positive ones.

Anger occurs at different levels of intensity. A small amount can be used constructively; however, high degrees of anger seldom produce positive results. Getting very mad or losing our temper prevents us from thinking clearly. We may then say or do things that we will later regret.

Aggression can get you into trouble. When we feel we’ve been taken advantage of in one way or another, we want to lash out at the person who offended us, even though that person may be the one who is closest and dearest to us. Sometimes we choose to explode before we think of the consequences to ourselves or to others.

Anger does not automatically become aggression. Wanting to hit someone and actually doing it are two different responses. Sometimes we hit the other person because it is the only way we know how to act. This is abuse and is the wrong way of dealing with our anger. Our anger responses are patterned and programmed—we were taught how to respond in childhood.

One of the most important things to do is to control your anger by recognizing your signs of tension, both internal and external. As you learn your trigger points and trigger signs, you can learn to relax, and your ability to handle anger will improve. Because anger is internally created, it can be internally managed.

Understanding the underlying causes for anger is the first step in resolution. When we recognize the anger and the initial hurt, we then have options to handle the feelings and resolve the conflict. Let’s look at the options:

Attack

Although it may dissipate the energy, an attack does not resolve the conflict. It will burn off the adrenaline, but it leaves the issue open-ended. This approach may also have consequences (such as broken relationships, arrest, detachment, rejection, and so on).

Denial/Running

To deny the situation and run from it leaves us with a feeling of helplessness and weakness. We feel victimized once more. We have no control over our lives. We are at the mercy of everyone else. This creates fear and anxiety.

Holding a Grudge

It stresses the body to hold a grudge. The blood pressure rises, the heart rate increases, and muscles become and remain tense. It places strain on the mind and body. We are more susceptible to further aggravation. It becomes easier to get angry the next time something triggers us.

Giving In

If we feel we are always the victim, this prolongs our anger. We collect the injustices, play the martyr, and live in the past. Anger is prolonged when we remind ourselves of past incidents that have upset us. When they are unresolved, we begin the anger process all over again in our minds. Memories of things that were unresolved can bring back our anger vividly, and it becomes a reality again and again.

RESOLUTION

Step 1: Take a Time-Out

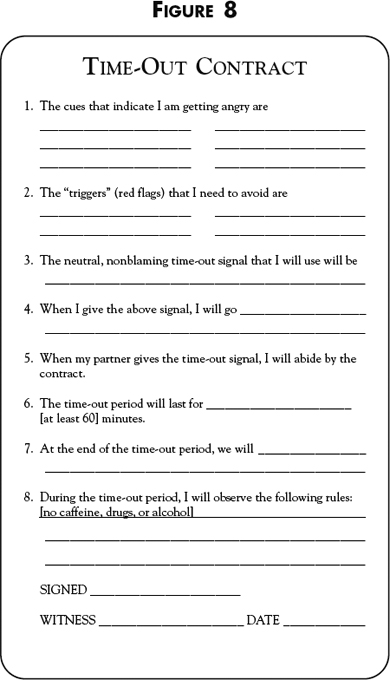

Impulse control is not a natural attribute; it is a learned behavior. It starts with delaying our responses. The moment you feel the escalation of emotions leading to anger, you need to take a time-out and define what you’re really feeling (hurt, rejection, helplessness, shame, guilt, or whatever else it might be). Consider using the Time-Out Contract (Figure 8).

Step 2: Recognize Your Feelings

Evaluate how upset you are and where this escalation could lead. How destructive could this be if you allow it to get out of control?

Step 3: Identify the True Cause of the Anger

What triggered it? What were the circumstances that created the emotions you’re dealing with right now? What is the reality of the situation?

Step 4: Evaluate the Anger

Is the anger legitimate, or did you perceive the situation wrong? Many times because of your wounds of childhood, your sensitivity, fears, anxieties, and rejection factors, you perceive things and experience feelings that are not necessarily reality. Step back from the situation and even get a reality check from a friend before taking action.

Step 5: Think Through the Situation

Do not take action until you have thought through the situation and have control of your responses, reactions, and words.

Step 6: Resolve the Conflict

After thinking clearly and seeing the reality of the conflict, you have many choices by which to resolve the conflict. You can confront calmly, set boundaries and limits, get unbiased wise counsel, express the feelings, negotiate resolution, compromise—or pass over the issue until a later time. You can simply let go. You have no control over other people, situations, or circumstances.

Step 7: Forgive

Forgiveness releases you from the mental grip of the person who offended you. Forgiveness does not condone the behavior of the perpetrator. Many times the perpetrator’s response is a false or pseudorepentance, so it does not require the other person to acknowledge what he or she has done. Forgiveness itself breaks the bond. Forgiveness does not require you to reestablish relationship with the offender. Forgiveness does not mean you have to go back and receive a second offense. You can forgive and yet set boundaries. Forgiveness starts the process of diminishing pain. The choice of forgiveness starts a process that takes time for the sting to be released from the memory of the event. You will probably never forget, but the pain will diminish.

The Process of Forgiveness

• Identify the event or trauma.

• Identify the person connected to that event.

• Choose to forgive.

• Identify your reactive behaviors connected to the event.

• Share the pain with someone you really trust.

• Focus on growth that develops character and maturity.

• Choose to stop the behaviors connected to the event.

• Maintain growth by positive self-talk, reaffirmation, and value statements.

This process creates a finish line in the mind. Closure begins the healing process.