Chapter Seven: Garbage Patrol

Me and Maggie was both ranch-raised but we went in different directions when we reached maturity. I stuck with the ranch life and went into full-time security work, and she moved to town.

For some reason she never took to ranch life. Growing up, it seemed that everything we pups did was either too loud or too dirty for her. Just to give you an example, we never could get her to go into the sewer with us. She just didn’t take to it.

She never cared a lick about chewing on smelly old bones either, or playing in the mud or digging holes. She didn’t even have an interest in cow work.

Moving into town was a good thing for her. She found a good home and staked out her own version of cowdog life, which always seemed a little strange to me but I wouldn’t want to judge anybody else.

Oh, and she never went in for nicknames either. The blessed woman will go to her grave calling herself Margaret and me Henry. She always thought Hank sounded undignified or something like that.

But even though me and Sis went our different ways, we remained close over the years, and she was always delighted when I dropped in for a visit. She kind of looked up to me as her big brother, see, and I think it kind of tickled her for me to drop in and talk to the kids about the old cowdog ways—you know, show ’em how country dogs lived and tell ’em some stories, that kind of thing.

Oh, every now and then she’d put on like she didn’t want her young’uns exposed to such crude ways, but I knew that down deep, where it really counted, she was glad to have me there with the kids. Who wouldn’t be? It ain’t every town kid that has an uncle who runs a six thousand acre ranch and fights . . . I guess I’ve already mentioned that. Anyway, her kids were pretty lucky.

Well, poor old Mag had that headache problem and had to go to bed with it. I stuck my head in the doghouse door and told her not to worry about the kids, I would take care of everything. She let out a groan. I guess that old head was really throbbing.

Well, I went out and called the children in from their play. “All right, kids, let me have your attention for a minute or two. Your ma has asked me . . .”

Little April, one of the girls, held up her paw. “Uncle Hank, Mom doesn’t allow us to call her ‘Ma.’ She says it sounds crude and backward. She says only dog trash uses that word.”

“I see. Well, by George if that’s what Mom says, that’s the way it’ll be. Your Mom has asked me to teach you little rascals a dab or two about your cowdog heritage.”

Roscoe stared at me with big eyes. “OUR MOTHER said that? Cowdog heritage?”

“That’s right, son, those were her very words, as I recall. I spoke with her only moments ago.”

“Wow! We thought she was ashamed of her family.”

I reached down and patted the lad on the head. “My boy, your ma . . . mother . . . mom, whatever she is, has always looked back on her cowdog heritage with enormous pride, and of course we all know what she thinks of your Uncle Hank.”

Four pairs of eyes stared up at me. It got very quiet.

“Anyway, at your mother’s request, I’m going to give you kids a few lessons in Cowdogology. I want you to pay attention and follow directions. Any questions?” One paw went up.

“Yes.”

It was Barbara, the other girl. “What does ‘ignert jackass of an uncle’ mean?”

I pondered that. “A donkey is a four-legged beast of burden, sometimes referred to as a jackass. If a guy had an uncle who was a donkey, he might refer to the uncle in that way. Any more questions?” The same little girl raised her paw. “Yes?”

“Are we kin to any donkeys?”

I got a chuckle out of that. It’s amazing how town kids really don’t understand basic concepts of biology. “No, sweetie, it’s not possible. All right, our first lesson will be, how to dig under the yard fence.” The kids looked kind of shocked. “What’s the matter?”

“Mom said we should never ever dig under the fence,” said Barbara.

“That’s exactly right, honey, unless Uncle Hank’s here to supervise. Everybody ready? Form a line and let’s move out.”

We marched across the yard in single file. “Left, left, left right left! Left, left, left right left! Straighten up that line! Pick up your paws! Stick them tails up in the air! That’s better. Left, left, left right left! Column . . . halt!”

They came to a halt in front of the fence and stood at attention. I walked down the line. “All right, I need four volunteers to dig a hole under the fence. You four right there. Stand by to dig . . . commence digging!”

Let me tell you, for a bunch of little town pups they did all right. There for a while the dirt was just fogging and it didn’t take them long to get a tunnel dug. Then I gave the order to commence burrowing. One by one, the kids dived into the hole and wiggled through to the other side.

I served as rear outlook while they went through, then I dived into the hole and joined them on the other side.

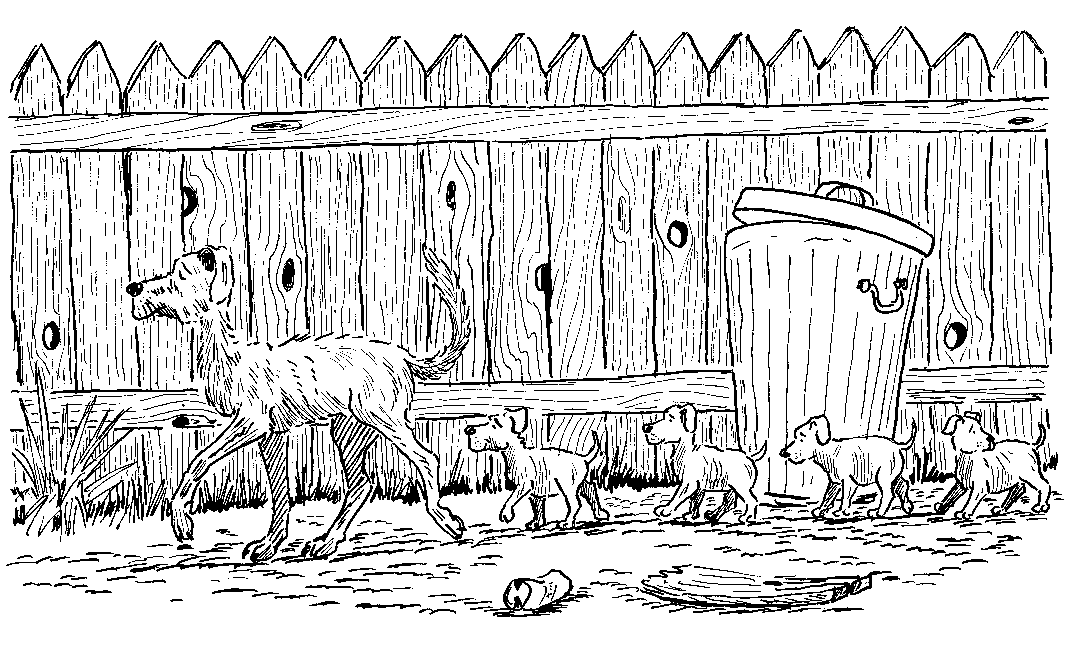

“All right, that was pretty good. I’m glad to see that we have some spirit in this outfit, some of that good old cowdog spizzerinctum. Now we’ll have a lesson on how to live off the land. We’re going to make a garbage patrol.”

I paced back and forth in front of them. “Suppose you were in a strange town. You didn’t know anyone, you didn’t have a place to stay, you didn’t know where your next meal was coming from. What would you do? Form a line and follow me. I’ll show you.”

We marched down the alley until we came to the first garbage can, which was a fifty-five gallon drum with the top cut out. I showed ’em how to go up on their hind legs, hook their paws over the edge of the barrel, and pull it over.

“All right, now you kids sort through that stuff and find some grub.” The boys gave a yell and went into the barrel, but the girls kind of hung back. “What’s the matter?”

April spoke up. “Mom says that playing in garbage is unladylike.”

Barbara nodded. “And we’re not supposed to get dirty. Mom said so.”

“Well, moms are always right, don’t forget that,” I said. “So go through that garbage in a ladylike manner and try not to get dirty. And don’t worry about your mom. I’ll take care of her.”

The girls looked at each other, grinned, and dived into the barrel with the boys.

They didn’t find much in that first barrel, just a couple of chicken bones and a whole bunch of newspapers, so we moved on to the next one. Same story there: corn cobs and potato peelings. By George, that was kind of a lean alley. We had to investigate a dozen barrels before we found a real treasure: a bunch of fish heads wrapped in newspaper.

Oh, the kids loved them fish heads! They jumped right in the middle of them and gobbled them down. I stood back and watched and, you know, kind of remembered myself at that age, when all at once a man stepped out into the alley. Guess he was dumping trash or something.

He looked up and down the alley. You might say we’d left a little mess. I mean, when you get all caught up in a garbage patrol, you don’t stop to think about the mess you’re making.

The man dropped his trash basket and came running toward us, yelling and waving his arms. “Hyah! Get outa here, go on!”

I sounded the retreat and we lit a shuck, headed south down the alley as fast as we could go. We went several blocks and hid in a hedge row. The kids were out of breath and all excited.

“Gosh, that was fun!” said Roscoe, and the others agreed.

“I was scared,” said Barbara. “I thought that old man would catch us.”

“Yeah,” said April, “he sure looked mean!”

“Uncle Hank,” said Spot, “I like fish heads.”

“And playing in garbage is fun!” said Barbara.

I smiled and nodded my head. “You see, kids? If we hadn’t gone on a garbage patrol, you never would have learned all this. As your mom’s told you many times, education is very important.”

I stepped out of the hedge and scouted the area to make sure the coast was clear, then I gave the password—“Stinkeroo,” was the secret word—and the kids formed a line and we went marching home. I figgered they’d had enough education for one day.

We were marching down the alley, maybe three blocks from home, when we passed a yard with a big cedar fence around it. Sitting on top of the fence was a big fat yellow cat.

My ears shot up and my lip curled, all on sheer instinct. I mean, my instincts about cats are pretty sharp. I glared at her as we went trooping by, just waiting for her to make some kind of smart remark.

You know my position on cats. I don’t like ’em. I don’t go out of my way to cause trouble with a cat, but any time I find one that’s shopping around for a fight, I can usually be talked into it.

Well, this cat looked dumber than most but she must have had a little bit of sense because she didn’t say a word as we went past. She just stared at us.

I supposed that was the end of it, but when we got past her, little Roscoe came trotting up to the front of the column. He had a worried expression on his face.

“Uncle Hank, that cat said something when we went past.”

“Hold it! Halt!” The column came to a halt. “What was that again? The cat said something? What exactly did the cat say?”

“She said, ‘Your momma wears combat boots.’ What does that mean, Uncle Hank?”

“What that means, young feller, is that we’re fixing to have a demonstration of violence and bloodshed. About face! Follow me!”

And we marched back to teach some manners to a certain lard-tailed yellow cat.