Chapter Four: The Case Is Solved

Itook one last look at the calendar: “End of the month clearance sale, Stockman’s Western Store.”

I heard Sally May gasp in the other room. “My cactus! Who . . . what on earth . . .”

I was sitting there in the midst of the steak blood, trying to decide what to do, when she appeared in the doorway. She looked at me and her mouth dropped open. “Hank! What are you doing in here!”

I gave her a smile and started whapping my tail on the bloody floor, as if to say, “Hi Sally May, how’s it going? I . . . uh . . . just got here and discovered that . . . uh . . . somebody stole your steaks, so to speak. And . . . uh . . . I realize that the . . . uh . . . evidence looks very damaging for me, but I would . . . uh . . . urge you not to leap to any . . . uh . . . hasty conclusions.”

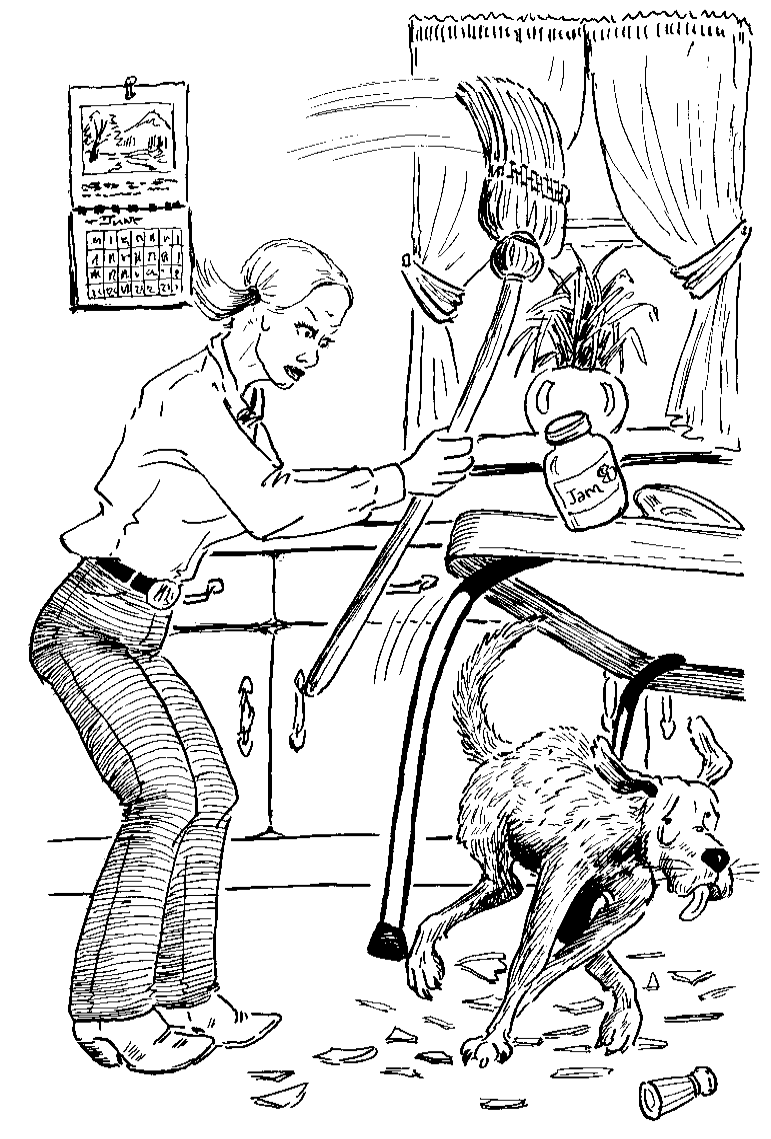

She was carrying the baby in one arm and a bag of groceries in the other. She set them down on the floor, reached into the closet, and came out with a broom. Her face was red and there were thunderclouds in her eyes.

“YOU ATE OUR LUNCH, YOU SORRY GOOD FOR NOTHING STINKING COWDOG! AND LOOK AT THIS MESS!”

How could I look at the mess when she was trying to hit me with the broom? Whap! She got me on the back. I tried to run, I mean I would have been glad to get out of her house but she had the door blocked. I ran in a circle and whap! She got me again.

So I did the only sensible thing a dog in fear of his life could do: I jumped up on the dinner table. Was it MY fault the jelly jar fell off and broke? Was it MY fault that she swung at me and hit the sugar bowl instead? I’ve always been the kind of dog who could take a hint. I can tell when I’m not wanted. When Sally May drew back her broom for another shot, I leaped off the table, ran between her legs, shot through the door, sprinted across the living room, and made a flying leap through the window. And then I ran for my life.

I went down to the feed barn, figgered that would be the safest place for a dog with a price on his head. The door on the feed barn was warped at the bottom and I squeezed through and took refuge inside.

I went to the darkest corner and hid between two bales of prairie hay. After a bit I heard the pickup and stock trailer pull up to the corral. The cowboys had come in for lunch and were putting their horses in the side lot. I could hear them talking and laughing about some extraordinary roping feat they had performed that morning.

They took their roping serious, those two guys. It didn’t bother them in the least that most of the sane and intelligent people in the world not only couldn’t rope but didn’t even want to learn. They seemed to think that if a guy could throw a rope he was something special.

I won’t comment on that. I have no tacky remarks to make about grown men who walk around swinging ropes. I learned long ago not to pass judgment on others, no matter how crazy they act.

Well, the cowboys headed for the house. I could hear their spurs jingling. The back door opened and closed. Exactly one minute and thirty-two seconds later, the door opened again and I heard High Loper’s voice: “Hank! Come here, you sorry devil! When I get my hands on you . . .”

I couldn’t make out the last part. Wind was banging a piece of loose tin on the roof. (If I’d had any say-so in the matter, that roof would have been fixed years ago, but nobody ever listens to Hank.) Anyway, I couldn’t make out the last part but I didn’t really need to. Loper wasn’t calling to wish me happy birthday.

He yelled for a while, then went back inside. Everything got quiet. I wondered what they were having for lunch. Whatever it was, you can be sure they didn’t starve.

I mean, you’ve got to put all this into perspective. Loper had missed one steak dinner, right? One meal out of a whole lifetime.

Okay, then you have me, the Head of Ranch Security, who had put in years of faithful service and had eaten scraps, garbage, tasteless dry dog food, and an occasional rabbit. Wasn’t I entitled to one steak dinner? Was that too much to ask for a whole lifetime?

Hence, through simple logic we discover that Sally May and Loper had ABSOLUTELY NO RIGHT TO BE MAD AT ME for eating a few crummy little steaks off their table.

Not only that but Sally May had been negligent in leaving the steaks unguarded. So there you are.

Well, the noon hour came and went. I heard the vigilantes out looking for me but I laid low and they didn’t find me. Finally they went back to work. I’m sure that broke their hearts, having to do a little work for a change.

When things quieted down, I heard Drover creeping around outside. “Hank? You down here? You can come out now.”

I stuck my head through the crack in the door, checked in all directions, and slithered out.

“Oh, there you are,” he said. “Boy, you sure got ’em mad up at the house. What did you do this time?”

“What do you mean, ‘this time’? This ain’t something I do every day just for sport.”

“No, I guess not. What did you do this time?”

I told him the story. “And as you can see, I was just doing my job and they’ve got no right to be sore at me.”

“I see what you mean,” said Drover. “Let’s see. You knocked over the cactus. You pulled the steak dish off the table. You busted the dish. You got blood all over the kitchen. And then you ate the steaks and knocked off the jelly jar. Well . . . what was Sally May so mad about?”

“See? That’s my point right there. I mean, your first reaction was the same as mine. I don’t know, I just don’t know. Maybe she and Loper had a fight this morning. Maybe the moon was in the wrong place.”

“Maybe she was worried about the end of the world.”

“Which brings us back to our investigation, Drover, and another little matter which you won’t enjoy hearing about.”

“Uh oh.”

“That’s a good way to put it.” I cleared my throat. “Drover, I’m afraid I must point out that you left your post in a combat situation, ran to the machine shed, abandoned your superior when he was trapped in the house with a frenzied, dangerous, possibly crazy woman, and otherwise behaved in a disgraceful, chicken-hearted manner.”

Drover looked at his feet. “Well, I was scared, Hank, and . . .”

“Spare me the details. Ordinarily this kind of cowardly behavior would have to be written up and put into your dossier. But I’m willing to forget the whole thing if you’ll give me one small piece of information.”

His face brightened and he started wagging his stub tail. “Sure Hank, anything you want to know, just ask me anything!”

I smiled, bent down to his ear, and whispered, “Who first told you that the world was going to end tomorrow at three o’clock?”

“Well, let’s see.” He scratched his head. “Was it you?”

“No. Think a little harder.”

“Well . . . gosh, I can’t remember, Hank.”

“Here’s a little hint: was it by any chance a cat?”

“A cat, a cat. Let’s see now. You were asleep and I was up by the yard gate this morning and . . . do you reckon it could have been Pete?”

I glanced off to the east and saw Pete basking in the sun beside the garden gate. He was purring and washing himself, which means that he was spitting in his paw and wiping the spit over his face. That’s the way a cat takes a bath.

I take tremendous pride in my personal appearance. I cultivate a rich, manly smell. I bathe regularly, in the sewer.

Now, let’s look at Pete. He takes spit-baths. Has anyone ever seen him in the sewer? No sir. But has Sally May ever referred to him as a stinking cat? No sir. So there you are, and that’s one of two dozen reasons why I hate cats and Pete in particular.

I had to get that off my chest. Now, where was I?

“Well, Drover, we’ve broken the case.”

“You mean the world’s not going to end tomorrow?”

“That’s correct.”

“Oh, what a relief! I tried not to show it, Hank, but I was mighty scared. But . . . are you sure we’re safe?”

“I saw the calendar. It didn’t say ‘End of the World.’ It said ‘End of the month clearance sale.’”

“Oh, that’s just wonderful!”

“Is it?”

“Well, maybe it’s not.”

“It may be good, Drover, but it’s not wonderful.”

“That’s what I meant.”

“It can’t be wonderful because we were duped by the cat.”

“You mean . . .”

“Yes, exactly. We broke the case but consider the price.”

He cocked his head to the side. “You mean . . . at the clearance sale?”

“No, that’s not what I mean, Drover, not at all. I did a flawless penetration of the house, conducted a near-perfect investigation, broke the case wide open. But my position as Head of Ranch Security has been compromised. How can I carry on my work when everyone on this ranch is mad at me?”

“Huh. I hadn’t thought of that.”

“Well, it’s time you thought about it, son, because I have no choice but to take a leave of absence until this thing blows over.”

“You mean . . .”

“Exactly. I’m leaving the ranch today and I’m liable to stay gone for a week—unless, of course, I’m offered a better position somewhere else, and then I may never come back.”

“Oh. Oh. Then that means . . .”

“Exactly. You’re in charge of security until I come back.”

Drover’s jaw dropped. “But Hank, I wouldn’t live on any ranch that would have me in charge of security.”

“Nor would I, but that’s the way this particular cookie has crumbled. So long, Drover, I’m hitting the road. I’ll see you in a couple of weeks—maybe.”

“No . . . wait a minute, Hank. Where you going? What if I need some help?”

“I’m going to town to visit my sister and maybe a couple of other women. If you get into a bind, if you need any help, if there’s an emergency of any kind, don’t hesitate to take care of it yourself.”

“But Hank . . .”

“So long, Drover, see you around.”

And with that, I marched through the sick pen, through the back lot, out the corrals, and headed north toward town.