31 January 1968

An entire generation of Americans remembers exactly what they were doing on the morning of 7 December 1941. Another generation remembers exactly where they were when they heard that President Kennedy was assassinated. Like them, for every American serving in South Vietnam at the time, 31 January 1968 is a date that will “live in infamy.’’ During the late night hours of 30 January and the early morning hours of 31 January, another generation of Americans was shocked to learn that the world as they knew it had been changed, dramatically, literally overnight.

Although American forces had been deeply involved in the civil struggle between the North and South Vietnamese since the early 1960s, up until that fateful night the Vietnam War was largely a pastoral war. It was an unbalanced clash between the world’s strongest military power and a poorly armed but deadly and elusive enemy force of ragtag soldiers called the Viet Cong.

Before 31 January 1968, most stateside Americans believed that it was only a matter of time before the pesky VC would be subdued. The notion of defeat was simply inconceivable. Although a few antiwar demonstrations had spontaneously erupted across the nation before that pivotal date, the demonstrations would now grow into intense and organized public resistance to a war that was escalating dramatically with ever-mounting casualties. As the public attitude toward the Vietnam War was dramatically changing, the reality for those fighting the war was also changing.

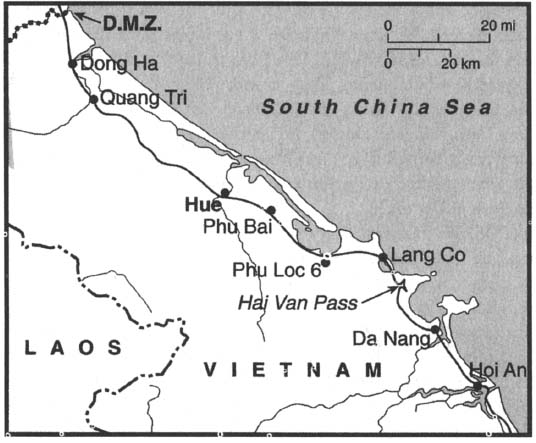

Prior to 31 January 1968, the Marines of Charlie Company, First Battalion, Fifth Marine Regiment (1/5), had become somewhat accustomed to long periods of boredom, shattered occasionally by a few minutes of the terrors found in the “battles” that the Viet Cong chose to fight. Long, strenuous, and unproductive patrols throughout the South Vietnam countryside were the order of the day. Throughout the long months of November and December 1967 and January 1968, the Marines of Charlie Company spent all their time conducting long, strenuous, somehow boring and yet terrifying patrols in the Hoi An and Phu Loc 6 areas of operations, or AOs. And then it all changed.

In the very early morning hours of 31 January, I awoke abruptly, my mouth fouled with the nasty taste of Southeast Asian humidity and not enough sleep. A strong feeling of panic welled up inside my guts. Although I was not wide awake, I was fully aware that something was wrong, badly wrong. Numerous explosions had rudely awakened me. I was not yet sure if they were real or the audio components of a vivid, very bad dream.

I checked the luminous dial of my Marine Corps-green, standard-issue plastic wristwatch; it was 0100 hours, an hour before Benny Benware, platoon radio operator for Charlie One, was supposed to wake me for my part of the watch. A myriad of conflicting thoughts rushed through my sleep-addled brain as I struggled to clear the cobwebs. These explosions were definitely not dream-generated explosions, because I was fully awake now, and they were still shattering the night. There was no particular pattern to them, no consistency like what you would expect during a mortar or rocket attack. About the only thing that I knew for sure was that the explosions were very large and, fortunately, quite a distance away from our present location. Although the sounds of distant explosions are often tricky in this type of terrain, it sounded like they were at least a few kilometers to the south, up Highway One on the Hai Van Pass.

As my eyes adjusted to the early morning blackness, I automatically scanned my surroundings. Although I couldn’t see many of them, I knew that the Marines of Charlie One were there, silent and invisible, quietly sitting in their two-man perimeter positions surrounding the Charlie One Command Post (CP). The Charlie One CP group included myself; Benny Benware, my radio operator; SSgt. John A. Mullan, our platoon sergeant; and “Doc” Loudermilk, one of the two Navy corpsmen assigned to Charlie One. The CP was situated roughly in the center of Charlie One’s perimeter, which was about a hundred meters in diameter. We were located about five hundred meters south of, and roughly one hundred meters above, the Lang Co Bridge. We were dug in on a low scrub-and jungle-covered “finger” of the towering, threatening mountain range that dominated the Dam Lap An Bay. The finger was covered with a thick scrub brush that afforded us some cover and concealment but was low enough to provide us some visibility of the surrounding terrain.

Our mission was to protect the Lang Co Bridge. The Lang Co Bridge was the longest bridge between Da Nang and the DMZ. It was also one of the few bridges along Highway One not protected by a cordon of barbed wire. Because of the bridge’s exposure, I had chosen to stay mobile and remain off the bridge during the long, dark nights, instead of taking up positions on the bridge itself.

For the past few days, since we had arrived in the Lang Co area, Charlie One had set up in platoon-sized ambush positions in a different location each night. Our mission was to stop any enemy approach to the strategically important bridge. Another Charlie Company platoon, Charlie Three, had the job of protecting the bridge structure itself. They typically stayed on the bridge with the Charlie Company CP group, or in the village of Lang Co, on the other side of the bridge.

The explosions continued relentlessly. Finally fully awake, I successfully pushed back the initial rush of panic that loud explosions in the night always caused. I reached out to touch Benny Benware, who was lying down about a meter to my right in a shallow depression on the damp ground. Benny crawled over to me immediately, his PRC-25 radio already mounted on his back, ready to move out if necessary. It was easy to see, even in the “zero dark thirty” gloom of the early morning hour, why all Marine radio operators referred to their PRC-25 radios as “Prick-25s.” The bulky, uncomfortable attachment to Benny’s Marine Corps-issue backpack added at least twenty-five pounds to his load, not including the added bulk and weight of several spare batteries. Somehow the tall, skinny Marine managed without a lot of complaining, but I was sure as hell glad that he—and not I—had to carry the Prick-25.

“Nothin’ comin’ over the company net yet, Lootenant,” Benny whispered in his nasal Tennessee twang.

I peered at Benware in the dark and asked, “How long has this been going on, Benny?” I had been sound asleep and couldn’t be certain that the first explosion had been the one that woke me up.

“Jist a couple a minutes, Lootenant. Sounds like they’re all coming from up the Hai Van Pass, but, shit, they ain’t nobody much up there tonight except Charlie Two. Jist that antiaircraft missile site at the top of the pass and them damn ARVN gooks at the French compound halfway up. Don’t sound like mortars or rockets, more like sappers is havin’ a shitpile of fun. And, they ain’t a single rifle blowin’ caps, at least not raht now.” For Benny, this was a long speech, perhaps even a filibuster. To those of us who knew him, speech for Benny Benware seemed to be almost painful. Benny was a man of very few words unless he was speaking into the Prick-25, doing his job. When he did talk with his buddies in Charlie One without the assistance of the Prick-25, his speech patterns were quiet and slow, and his face would scrunch up as though the utterance of a few words was somehow more difficult than weight lifting. When the shit hit the fan, however, like when Charlie One got into a firefight or some other scrape and we depended upon Benny’s skills as our only link to larger forces or the necessary supplies for a Marine combat platoon in the bush, his speed and volume would increase considerably. But it still seemed to hurt him to talk.

I thought about Benny’s assessment of the situation for a few minutes and agreed. We knew that one of our sister platoons, Charlie Two, was on its own up in the Hai Van Pass tonight and was broken down into squad-sized ambushes. They, or more likely the antiaircraft missile site on the pinpoint-sharp mountaintop just above the summit of the Hai Van Pass, which protected the northern air approaches to Da Nang, were probably being hit by Viet Cong sappers. The sappers were the terrorists who sneaked up on you and tossed a few satchel charges at you in the dark of the night.

The Hai Van Pass was aptly named. The Vietnamese word hai means “ocean,” or “sea,” and van means “cloud.” The Hai Van Pass was definitely a place where the ocean meets the clouds. The Vietnamese highlands, which dominate the western regions of this long, skinny country, thrust eastward toward the sea in this area only a few miles north of Da Nang. The mountainous highlands protruded into the South China Sea north of Da Nang Bay. The Hai Van Pass allowed travelers on Highway One to proceed north to Lang Co and beyond via a twisting, turning two-lane road.

During the past couple of weeks, since moving out of the battalion fire base at Phu Loc 6 in mid-January, Charlie Company, 1/5, had been assigned to the Lang Co AO. The Lang Co AO was a territory that started at the base of the mountain pass about eight kilometers north of the Lang Co Bridge and extended south past the Lang Co village and bridge, up the Hai Van Pass, another ten kilometers, to the top of the pass. The primary mission of Charlie Company in the Lang Co AO was to protect Highway One, the critical, and only, land supply route between Da Nang and the DMZ. If the enemy were allowed to shut down Highway One in the Lang Co AO, the only methods of resupply for the vast American forces north of us would be through the air, or possibly by sea.

The Lang Co village at the north end of the bridge was populated predominantly by Catholic Vietnamese villagers considered friendly to American and Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) forces. But the area south and west of the Lang Co Bridge, and the entire Hai Van Pass area, were constantly exposed to attacks by the Viet Cong.

From Lang Co, travelers on Highway One crossed the Lang Co Bridge, then proceeded south toward Da Nang. Once across the thousand-foot-long bridge, the road turned sharply left and headed east toward the South China Sea. After meandering east a couple of kilometers along the inlet to the bay, the two-lane dirt highway then made a sharp hairpin turn back due south. At that point, even in daylight, travelers on Highway One were lost from view to those remaining behind on the bridge. The big, lumbering convoys of Army and Marine Corps “six by” trucks and the small, gaudy, overcrowded “gook buses” dominating the constant flow of vehicular traffic north and south on Highway One were seemingly swallowed up by a rugged mountain range that flanked the winding dirt road almost all the way into Da Nang. The ramshackle huts so common on the outskirts of Da Nang began to appear about thirty kilometers south of our position on the bridge.

Well-built reinforced concrete bridges had been erected over the mountain streams crossing Highway One by the French during their many decades of occupation. Between each large stream were several small streams. Culverts in the small streams allowed Highway One to continue steadily, although steeply and precariously, to the top of the pass. The vertical rise from the Lang Co Bridge to the top of the Hai Van Pass was over seven hundred meters. This may not sound like much to the uninitiated, but to those who humped and drove it, Highway One through the Hai Van Pass was like a highway through hell.

Since I had grown up driving the dirt logging roads and back country roads of Southwestern Oregon, I was accustomed to nasty back roads and steep drop-offs. But along Highway One through the Hai Van Pass, I definitely preferred walking. The terrain was extremely rough. The once-paved, now mostly dirt two-lane road rose over six hundred meters (nearly two thousand feet) in just the last three kilometers approaching the top of the pass. The many switchbacks and hairpin turns along the Hai Van pass had terrorized truck drivers for years as convoy after convoy slowly moved their critical supply loads north from Da Nang toward Phu Bai and the critical American and ARVN outposts along the DMZ.

Over the past few weeks, attacks on the convoys in the Hai Van Pass, which seemed to be the Viet Cong’s favorite ambush area, had been steadily increasing. Before the end of 1967 only about one in ten convoys had been attacked and damaged at some lonely hairpin curve of the steep and uneven roadway. In early 1968 that percentage rose sharply. The convoy truck driver’s mentality was to always maintain as high a speed as possible (with the belief that a fast-moving target is much more difficult to blow up than a slow-moving target), but that was just not possible on this section of the highway. At best, the heavily loaded six-by trucks were forced to shift into a very low gear as they made their way up the steep road at about twenty miles per hour or slower. At a couple hairpin turns they had to come nearly to a stop to stay on the road. In short, the trucks were easy prey for a well-prepared, well-hidden team of Viet Cong equipped with a nasty and deadly variety of high-explosive devices. After detonating their mines or shooting off their rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) rockets, the Viet Cong had an easy escape route up into the high reaches of the silent, jungle-covered mountains.

Since arriving here, Charlie One had spent many long hours patrolling up and down this tortuous section of the Hai Van Pass and the area west and south of the Lang Co Bridge. We never actually saw an enemy unit during those two weeks, but several truck convoys were ambushed in broad daylight and suffered spectacular destruction. Even while keeping their feet stomped down on the gas pedal, many convoy truck drivers and those riding “shotgun” with them were killed. Viet Cong ambushes were causing severe damage by hit-and-run tactics and were beginning to disrupt the critical flow of American supplies from Da Nang northward, and they were usually getting away with it.

Charlie Company’s new commanding officer, 1st Lt. Scott Nelson, had assumed command from the previous company commander only a couple of days before. So far he had spent most of his time in and around Lang Co village with Charlie Three, leaving the security of the Lang Co Bridge and the Hai Van Pass to Charlie One and Charlie Two. The Delta Company of 1/5 occupied a small artillery firebase that dominated a smaller mountain pass to our north, and they were responsible for their own security. They were important to us, however, since the 105-mm and 155-mm guns at the Delta firebase were the only artillery in range of our positions in the Lang Co AO.

The distant explosions to the southeast continued their sporadic clashing choruses, keeping me on edge. I was very aware and concerned that if Charlie Two was getting hit, we would probably have to react quickly and go to their aid. From this distance, it didn’t sound like a fixed position was getting overrun, but rather like H&I (harassment and interdiction) fire. The only problem with that supposition was that the enemy in this area was not supposed to have any heavy artillery or rockets. My mind went back to Benny’s theory that we were hearing the results of sappers.

Benny interrupted my thoughts: “Radio traffic from Charlie Two to Six. Wait one.” Benny listened in as 2nd Lt. Richard L. Lowder, platoon commander of Charlie Two, communicated with Lieutenant Nelson (Charlie Six). I waited about thirty seconds before Benny spoke again, in a stage whisper, he said, “Shit, them gooks is blowin’ the bridges all the way up the Hai Van. Now we’ll never get up to that mess hall at that antiaircraft missile base. Damn me all to hell!”

I had heard about the famous mess hall at the antiaircraft missile base, which, due to its proximity to Da Nang and the supposed importance of the base’s mission, was constantly supplied with fresh eggs and other culinary delights. I could empathize with Benny’s concern. But I was starting to get annoyed with him, since I wanted to know what the hell was going on up in the Hai Van Pass. Marines in combat could think about the strangest things at the most awkward moments, and Benny was no exception.

I grabbed Benny’s arm and, in a loud whisper, got his attention: “Dammit, Benny, stop worrying about that skinny gut of yours for a minute, and tell me what’s going on!”

“Raht away, Lootenant. Charlie Two Actual says that all the bridges and culverts on our side of the Hai Van Pass has been blowed up! He had Charlie Two broke down into three squads in ambushes, and they were settin’ about a hundred meters above Highway One, just off the streams, hopin’ to catch Victor Charlie comin’ down the mountain. It ’pears that Charlie snuck around all of his ambushes after dark, crossed the road between the bridges, and came in from below. Them gooks set charges on all the bridges and culverts, and now there’s nothin’ left of Highway One. Charlie Two estimates at least twenty major explosions. No contact with any gooks. They just blew the bridges and di-di mau’d.” Since I knew that di-di means “go,” and that mau means “fast,” I knew that the VC had made themselves scarce.

From my own firsthand experience of the Hai Van Pass, if what Charlie Two had just reported was true, this was not good news. There were at least six or seven large mountain streams that cut across Highway One between our present location and the night ambush sites of Charlie Two. While the destruction of Highway One’s bridges and culverts would not pose a problem to Charlie Two’s Marines, since they were on foot and could ford the streams without too much difficulty, the loss of those bridges would cut off our food and ammunition supply. Up until this point, our supplies had come via trucks from Da Nang or Phu Bai, the locations of the two largest concentrations of U.S. military personnel in I Corps. If the enemy had succeeded in closing down Highway One even for a short time, it would put a major crimp in the logistical plans of American forces in the northernmost corps (I Corps) of the four designated corps zones. (The “eye” in I Corps is really the Roman numeral one, but no one ever called I Corps “One Corps.” The others are called II (two) Corps, III (three) Corps, and so on, but I Corps was always called Eye Corps.)

In the three southernmost corps areas—II Corps, III Corps, and IV Corps—Highway One was an important artery of motor vehicle traffic, but it was not the only route available. Several other east/west highways were linked by other north/south routes in the highlands of II and III Corps and the Mekong Delta that dominated IV Corps. In I Corps north of Da Nang, Highway One was the only north/south route for ground transportation.

My thoughts were rudely interrupted by more distant explosions. But this time, the explosions were louder and were coming from the exact opposite direction of the fireworks that had interrupted my sleep. These explosions were coming from the Delta Company firebase, several kilometers northwest of us. Since we were on relatively high ground and Delta Company’s firebase was on even higher ground, with nothing between us but the broad, dark water of Dam Lap An Bay, this fight was clearly visible as well as audible. It was immediately apparent that Delta Company had come under heavy enemy attack. This time the explosions were accompanied by the syncopative percussion of enemy mortar and rocket fire interspersed with an increasing volume of small-arms fire. Enemy 82-mm mortar rounds and the enemy’s deadly RPG rockets were easily distinguishable as they impacted various points within Delta Company’s firebase. Red and white tracers from small-arms fire erupted with a surprising intensity, the red tracers emanating from the position we knew to be Delta Company’s firebase; the white or light green enemy tracers tracking inward from the enemy positions above and westward of the firebase. The shit was hitting the fan big time at the Delta Company firebase.

“Jesus H. Christ. What the fuck is going on?” I thought I was thinking this, but I must have muttered it out loud, because Benny answered, “I don’t know, Lootenant, but it sure as shit looks like the whole fuckin’ area around us is gettin’ blowed away.”

“No shit, Benny.” Turning away from Benny, I found Staff Sergeant Mullan lying prone a few feet away in the gloomy darkness and whispered to him, “Get word to the squad leaders to put everyone on one hundred percent alert until further notice, and then have them come in here for a quick briefing.” Sergeant Mullan grunted acknowledgment and quietly scurried away. I looked over at Benny and said, “Benny, get me Charlie Six Actual on the horn.”

The order I had asked Sergeant Mullan to pass on to our three squad leaders was probably unnecessary, but I wasn’t taking any chances. I had gotten to know the people around me very well during the past few months, walking with them down the jungle trails and back roads of Vietnam. Our nights in the bush were constantly sleep-impaired, and I was sure that every one of the fifty-one Marines of Charlie One was wide awake and watching the show. It was the nature of the combat Marine in Vietnam to be sound asleep, dreaming exotic dreams of the World one moment, and then the least little noise in the bush, and most certainly any explosion, no matter how distant, would bring him wide awake. But, again, I wasn’t taking any chances. Based on what was going on all around us, an attack on the Lang Co bridge could happen anytime.

I also wasn’t sure I could tell the squad leaders anything they didn’t already know when they got to the platoon CP in a couple of minutes for my briefing, but maybe Lieutenant Nelson could enlighten me.

Benny prodded me with the telephone-receiver-like handset from the Prick-25 and muttered that Charlie Six Actual was on the horn. I grabbed the handset, squeezed the activator, and verbally confirmed that I was listening. “Six Actual, this is Charlie One, over.”

The back-and-forth banter of tactical radio conversations had by now become second nature to me in my two and a half months in Vietnam, but it always reminded me a little of playing combat when I was a child, and it made me feel slightly self-conscious. If it were light enough to see, I’m sure that a slight grin would be evident on my face.

I knew that Scott Nelson was grinning as well. I knew he was grinning because over the past several days I had gotten several chances to observe him using the radio since he had assumed command of Charlie Company. Every time I had watched him he had worn this unerasable shit-eating grin, as if he were going out to play a big football game. He looked excited, anticipatory, and seemingly not the least concerned with any threat whatsoever.

First Lieutenant Nelson was a big man, at least six foot two and over two hundred pounds, but he had a baby face and nearly transparent blonde hair, with very few whiskers or mustache hairs. When we were first introduced, after he had extracted himself from the CH-34 helicopter that had dropped him off on a dirt landing zone just south of the bridge, I had experienced instant pangs of doubt and concern. As quickly as possible I had veiled the shocked realization that this seemingly overgrown adolescent was now Charlie Company’s “skipper,” although no one would refer to him as that until he proved himself in the bush. He had seemed okay over the past several days, but not much had happened, either.

“Charlie One, this is Six Actual. Sit rep, over.” Nelson’s squawking voice broke my reverie and brought me back to the present.

I answered back, “Six, this is One. We’re sitting tight. No contact, but we can see Delta’s firefight. We’re hearing multiple explosions south of us up the Hai Van Pass. What’s Charlie Two’s status, over?”

Nelson’s voice responded clearly through the squelch of the radio, “Charlie Two has no contact at this time, but they report major damage to bridges and culverts on Highway One. They’ll sit tight until first light, and then assess damage and report in. Millbrook Delta is under heavy attack with mortars, rockets, and small arms. Delta should be able to hold their position. You’re to sit tight, restrict radio traffic, and maintain security on the bridge. You may come under attack. Adjust your positions as you see fit. I’ll be staying over on this side of the bridge with Charlie Three, and we’ll protect your backside if things start happening over there. Lang Co Bridge must not be destroyed. You must hold your positions and defend the bridge at all costs. Don’t expect much in the way of artillery or air support, it appears all the firebases north and south of us are under attack. I’ll let you know when I know more. Over and out.”

Nelson sounded as frustrated as I felt. The shit was definitely hitting the fan all around us, but we knew very little about what exactly was going on. The situation in the Lang Co AO had changed dramatically, that was certain. It felt something like being in the eye of a hurricane, but a hurricane whose rain and wind were steel and fire. It was quiet and calm in our immediate vicinity, but the winds of war were raging all around us. As I waited for my squad leaders to report in, I reflected back on the events that had occurred since I had arrived in Vietnam three months earlier.

I arrived in South Vietnam on 15 November 1967, wet behind the ears and scared nearly speechless, although I tried very hard not to let anyone know that dismal fact. My fearful condition had been formulated by a combination of my training experiences and by some information I got, quite by chance, just before I left Quantico for WestPac duty.

I was one of a handful of young men who went through both the Marine Corps’ boot camp and the Infantry Training Regiment (ITR) in San Diego and Camp Pendleton, California. I had also gone through Officer’s Candidate School and Basic Infantry Officer’s Training (Basic School) in Quantico, Virginia. A Marine recruiter convinced me that if I enlisted in the Marine Corps for four years, I could put in for the Marine Corps’ MarCad program, where enlisted men were sent to Pensacola, Florida, given Marine Cadet status, and taught how to fly jets. If I got my wings, I would also get a commission.

After three weeks in boot camp, I finally scrounged up the courage to actually speak to a drill instructor, beyond a response to his question or instruction. I provided this particular drill instructor, an E-5 sergeant named Callahan, with a few minutes’ entertainment when I asked him, very respectfully, how I could sign up for the MarCad program. When he finally stopped laughing and had wiped the tears from his eyes, he looked at me and, in that singular fashion that only Marine Corps drill instructors can demonstrate, said, “Get the fuck outta my face, shitbird. There ain’t no such thing as a MarCad program, and hasn’t been since 1962.”

Although I had been terribly deceived by my recruiter, I had been in boot camp long enough to see what happened to dissenters. Their punishment was to be sent back to the dreaded “Day 1.” I decided to keep my mouth shut and do what I was told. I made the best of it.

A few days before graduation from boot camp, Sergeant Callahan called me into his office. After I went through the now-automatic and obligatory rituals of reporting to the drill instructor, Sergeant Callahan asked me if I had been serious about wanting to fly airplanes. He looked at me with his typical disdain and said, “Although you are still only a shitbird, you have kept your mouth shut and your nose clean. You will graduate as a squad leader, and we will put you up for promotion to PFC outta boot camp. If you really want to fly them damned planes, I’ll make you a deal.”

I was wary of any “deal” being offered by a Marine DI, but since he seemed sincere, I decided to take a chance. Shouting as loudly as possible, I said, “Sir, the Private is very interested in going to Pensacola, sir.”

Sergeant Callahan said, “Okay, shithead. Here’s the deal. I give the PFC promotion to one of these other poor slobs who will need it more for his enlisted career, and I recommend you for the Enlisted Commissioning Program. You gotta go to OCS in Quantico, get a commission, and then you gotta put in for Flight School in Pensacola. That’s the deal. You wanna try?”

I was well aware that the vast majority of my peers in boot camp would be getting orders to the other OCS (Over the Choppy Seas) as infantrymen, so I figured I had very little to lose by trying. I accepted the deal, and Sergeant Callahan was good for his word. I was accepted into the Enlisted Commissioning Program, completed OCS in the prescribed ten weeks, and got my commission as a second lieutenant in March 1967. I immediately put in a request for Flight School and was told that I would have to complete the twenty-one-week Basic Infantry Officer’s School for new Marine officers and that I could request Flight School from there.

It was about halfway through Basic School, in the hot and sweaty summer of 1967, that I was finally told that I was physically unsuitable for Flight School, due to a sinus blockage (having had my nose smashed several times in football games). That was it. I was destined to be a ground pounder.

Although I was never a top scorer in OCS or Basic School, I competed well enough in the challenging physical and mental games of OCS and Basic School to be given my first choice of military occupational specialty (MOS). I decided on Supply. After a year in the military, I had learned two very important things about a profession in logistics: first, a supply sergeant or supply officer was everyone’s best friend; second, and probably more importantly, supply officers very seldom left the comfort and security of a rear area.

That was when Capt. Jack Kelly made a significant impact on my life. Captain Jack, or Smilin’ Jack, as we called him when he wasn’t listening, was our Basic School platoon commander. He was an early veteran of the Vietnam War and had been awarded the Silver Star for his part in Operation Starlight, the largest American combat operation of the war thus far. He was also a very convincing motivator.

During my fifteenth week in Basic School, after I had submitted my request for a Supply MOS, our platoon of forty or so new second lieutenants was on a run out on some deserted dirt road in the back woods of the Marine Corps base in Quantico, Virginia. Since I am over six feet tall, I was running in the front of the platoon, in the position of a squad leader. About halfway through our run, Captain Jack surprised everyone by hollering at me and ordering me to fall out and drop behind. He wanted to have a little chat with me. I dropped out of the formation and fell about fifty feet behind the running platoon, where Captain Jack was trailing.

As I fell into position beside the still-running Smiling Jack, he didn’t waste any words. He said, “You’ve put in for Supply, Lieutenant Warr?” It was a question, but it wasn’t a question.

“Yes, sir. I want to be in logistics, sir,” I replied.

“Okay, you’ve earned the right to be given your first choice of MOS, so if that’s what you want, that’s what you’ll get.” I continued to look straight ahead, not understanding why we were having this conversation. “But I just want you to consider this one fact before you make up your mind.”

“Yes, sir.”

“See that shitbird college graduate up there at the end of the formation, Warr?” Kelly didn’t have to point for me to understand whom he was talking about. At the end of the formation, a short, very unmilitary young second lieutenant was struggling to keep up with the rest of the men. Every four or five paces, he would get out of step and would either threaten to step on the heels of the man in front of him or fall behind a couple of paces. The increasing human demands of the Vietnam War had resulted in an erosion of the Marine Corps’ normally very high standards. Men were being given commissions in the Marine Corps then who, a couple of years before, would never have made it through the first couple weeks of OCS, let alone Basic School. I knew what Kelly was talking about.

“Yes, sir,” I said.

“Well, if I give you Supply, that shitbird is going to get Infantry. You have friends from boot camp who are already in the ’Nam, don’t you, Warr?” Kelly knew that I had been through boot camp.

“Well, if that shitbird takes over a platoon in the ’Nam, he’s going to get some people killed, if you get my drift. That’s the guy that should be a supply officer.” Kelly kept up his steady, “recon shuffle” pace, never looking at me during this conversation.

“Yes, sir. If you say so, sir.”

“It’s your choice, Lieutenant. If you request Supply, I’ll give you Supply. On the other hand, I’ve been watching you, and I think you could make a fine career for yourself in the Marine Corps. Only a few of these men will be given ‘regular officer’ status when they leave here; most will be reserve officers, and they will get out after their tour is up. Regular officers get their choice of duty assignments and get put on the fast track for promotion. So here’s the deal: You request an Infantry MOS, and I’ll put you in for a regular commission. Think about it. Now, fall back in with the others.”

The next day I requested an Infantry MOS, and true to his word, Captain Kelly put me in for a regular commission. I was a ground pounder and was headed for WestPac.

None of this would have mattered a bit if it hadn’t been for one more, seemingly insignificant thing that happened to me while I was still in Basic School. I took a test and didn’t fail it. It was called the Army Language Aptitude Test (ALAT), and unlike the vast majority of my peers, I didn’t get a rock bottom, 0/0 score. I think I got a 1/2 out of a possible 5/5 score, which indicated some aptitude for a foreign language, at least in comparison to my peers. My now “proven” ability lead to my being assigned to a six-week high-intensity language training program at Quantico right after Basic School, along with eleven other second lieutenants.

For six weeks, eight hours a day, the twelve of us struggled to learn Vietnamese. We didn’t think anything of the fact that our instructors were Americans, staff NCOs who had spent tours in Vietnam, or that we were learning the Hanoi dialect. After a few weeks, my classmates and I babbled away at each other and actually seemed to communicate. A two-star general showed up at our graduation and told us that we would be put into strategically important positions where our newfound language skills would help make a difference.

Still, none of this would have made any difference in my military experience whatsoever. In my fifth week of the language school, however, something seemingly insignificant made a serious impact on my state of mind. I just happened to pick up a copy of a military newspaper that reported, every week, the deaths of American fighting men in South Vietnam. I had read this information many times before, had seen the ranks and names of the dead many times before, but until this moment that’s all they were: the names and ranks of dead people. Since I didn’t know any of them, their death had been totally unreal to me. However, this particular issue listed the names of four or five second lieutenants who, a short five weeks ago, had been my classmates in Basic School. One of them had been the top man in our class. These five young men had left Quantico five weeks ago, had taken their obligatory thirty days’ leave, had said goodbye to their friends and families, and had been promptly killed during their first week in combat.

This was not possible. These were all guys who knew what they were doing, and now they were dead. It was a moment that I remembered long afterward. It was the moment that the first seed of doubt entered my mind. I was shocked and no longer fearless. I began to think, for the first time, that maybe, just maybe, we were not prepared for this war.

I graduated from the language school, took my thirty-day leave time, and flew, via Okinawa, to South Vietnam. After going through processing in Da Nang at the First Marine Division Headquarters, I was assigned to the Fifth Marine Regiment, who were then stationed in the Hoi An area, about thirty kilometers south of Da Nang.

When I arrived at the Fifth Marines’ compound, decisions were being made as to which battalion would be my new home, and I found myself with a little time on my hands. Seeing a Vietnamese farmer walking across a grassy area inside the regiment’s compound, I decided to try out my newly learned language skills. Approaching this farmer, an old man with his mouth filled with betel nut, I said hello.

“Chao, Ong,” I cried out, remembering to make the phrase sound like “Chow Om,” as we had been taught.

The man looked at me with fear in his eyes and tried to continue on his way, muttering something that I couldn’t understand. I tried again, several times, smiling so that he could see that I was no threat to him in any way, that I was only interested in a little conversation in his native language.

We never communicated. After about five minutes of trying and failing to use the most basic greeting, “Hello, sir,” the panic in his eyes made me understand that he hadn’t understood a word I had spoken. As he hurried away from me, I finally realized that the words he was saying to me were that he was sorry, but that he didn’t understand English.

That was my first and last attempt to use my Vietnamese language training. The South Vietnamese dialect was as different from the Hanoi dialect as was the language used by a rural farmer from Alabama and a fifth-generation Bostonian. Further exacerbating the situation, try as they did, our instructors had not succeeded in making us understand just how important inflection is to the Vietnamese language. We had talked about inflection, but we really didn’t understand that a single word in Vietnamese could mean five different things based upon how it is spoken, its inflection.

The only benefit that I received from the Language School was reading that newspaper and seeing the names of the dead men. Reading their names shook the foundations of my confidence in our tactical training and opened my mind to the fact that how we were trained had not prepared us well for how the war was being fought. Thus, when I was finally assigned as the platoon commander of Charlie One a couple of days later, I had made up my mind to “hide and watch” for a while.

Oh, to be sure, for all appearances I immediately assumed command of Charlie One and called all the shots from the beginning. There was no way that I could act otherwise and not be instantly castigated and possibly prosecuted for dereliction of my duties. I was assigned as the platoon commander of Charlie One, and Charlie One had to fight the war on the day that I had taken over. The problem was that deep down inside of me, I was terrified that I was not ready to be in command and that I would do or say something that would get people killed. I decided to approach Staff Sergeant Mullan quietly and ask for his help.

Charlie One had been operating in the Hoi An area of operations for several months. I had gotten my assignment because the former Charlie One Actual had been killed by a command-detonated mine a month before I arrived. Sergeant Mullan, the platoon sergeant, had been acting as platoon commander since that day, and it was immediately apparent that the men respected him and that he had what I needed, experience.

I asked to speak privately to him, and simply and quietly explained my concerns. I told him that I was afraid that I would do something out of ignorance of the situation that might end up hurting one or more of the men, and I asked him if he would be willing to help me without the rest of the men knowing. After briefly thinking over what I had said, he agreed that it would not be right if the men knew what I had suggested, but that he would do everything he could to help me get up to speed. We worked out an “on the job” training program that would have all the appearance of my being totally in charge while the training period lasted, and we worked out a way to have a few minutes alone together at least daily. I told Sergeant Mullan that it would be up to him to let me know when he thought I was ready to take command in both name and actual fact. After about four weeks, Sergeant Mullan took me aside, thanked me for my concern, and let me know that he thought that I was totally ready for command. This arrangement proved to be one of the best decisions I made while in Vietnam. I don’t think any of the men ever knew how much I had relied upon Sergeant Mullan during those early days.

My thoughts of those long Hoi An days were interrupted momentarily my another update from Benny Benware. According to the information that he had overheard on the battalion net, the bridges had all been blown between here and Da Nang, and it looked like everyone north of us was fighting for his life. Helpless and frustrated, I couldn’t stop the constant mental exercise inside my brain. I continuously asked myself, “How the hell did I get here, and what should I do next?”

Waiting in the dark and shattering night for my squad leaders to arrive, it was difficult to think about anything except the awesome display of the firefight at the Delta Company firebase across the empty waters of the bay. I couldn’t change or even remotely influence the explosive events of this unforgettable first night of what would soon be called the Tet Offensive of 1968.

On Christmas Day, 1967, 1/5 moved en masse from Hoi An to Phu Loc 6, located about fifty kilometers north of Da Nang. The fighting in early January at Phu Loc 6 had been intense, especially in comparison with our contacts with the VC in the Hoi An area, but even at Phu Loc 6 our enemy was elusive, reluctant to show itself, seemingly content to lurk in the jungle and throw rockets and mortars in our direction. But now, from the sounds of the fighting north of us, the enemy had apparently decided to attack massively. I was having a hard time understanding why the Lang Co Bridge hadn’t been hit.

Lang Co was the largest bridge by far between the DMZ north and Da Nang to the south, a distance of nearly one hundred kilometers. It was also the only bridge that could not have been replaced with a pontoon bridge or other temporary bridge structure had it been destroyed, because of strong tidal currents running back and forth from the Dam Lap An Bay and the South China Sea. The bridge’s span covered mud and water for nearly a half kilometer from shore to shore. Although during low tide much of the bridge covered mud fiats, the channel under the center span was unusually swift and very deep. During high tide, the entire half-click (half-kilometer) span was under another ten or more feet of water. Strangely enough, although the destruction of this one bridge would have dealt the most severe blow to U.S. and ARVN supply lines, it was the only bridge not blown up, at least so far, between the top of the Hai Van Pass and the Delta Company firebase. We would find out soon enough that the Lang Co Bridge was the only significant bridge left standing between Da Nang and the DMZ when that long night ended.