10–11 February 1968

Charlie Company was picked up the following morning, 10 February 1968, by several Army Chinook CH-47 helicopters, after the dual-rotor workhorses disgorged their loads of fresh Army infantry troops. A quick briefing was conducted by Scott Nelson for the benefit of the Army officers who would now be responsible for the Lang Co AO.

As the Army filed off the helicopters and the Marines prepared to board for the short hop to Phu Bai, a longstanding tradition in the American military establishment took effect. A loud, dull roar of many disparaging remarks between the two groups erupted. While most comments were made in fun and not to be taken too seriously, the trash talk would have made an outsider blush.

“Yeah, this is typical. After the Marines have cleaned out an area, they send in the Army to babysit the civilians.”

“Oh, yeah, we heard you Marines got your butts handed to you up here, so they had to send the Army in to straighten out the VC.”

“Hey, get some, you scumbag doggie! Keep yo’ head down!!”

“Yeah, right, leatherface, leave just while the fun is starting.”

And so on. . . .

Despite my desire to see the inside of the Phu Bai mess hall and to get out of the Lang Co area (the scene of much hunger and other forms of anxiety), I found myself rather reluctantly boarding the CH-47. Somewhere in the back of my mind my instinct toward self-preservation was beginning to assert itself. There was a logical connection between leaving the eye of the hurricane and subsequently having to go right into the substance of the deadly storm.

I looked around the loaded helicopter at the Marines of Charlie One to see if I could read their expressions, to see if I could figure out what they were thinking at that moment. Their faces were masks; they were the faces of well-trained actors, of men who had been indoctrinated with the history of the Marine Corps. I could see reflected the macho reputation of the infantry Marine and a great belief in the Marine Corps’ unequaled history of overcoming great odds. These men totally accepted their destiny as active participants in a battle that would result, for the Marines, in certain victory. They seemed to project no doubt that whatever challenge lay before us was easily conquerable. They all seemed to be looking forward to whatever came next. There was no fear, no uncertainty, painted on those young faces. Was I the only one who worried about what would happen, now that we were venturing into the storm?

Maybe they were simply thinking about the mess hall. Perhaps, for them, nothing else on this earth mattered as much as the prospect of some Marine Corps chow, served hot on a dented and scratched metal tray. Any mess hall chow was better than the best C ration meal, and it beat the hell out of village rice any time.

Unable to read anything significant on the young faces of Charlie One, my thoughts turned inward as the CH-47 tilted forward and lifted off in a great cloud of dust, and the Lang Co Bridge rapidly became small and insignificant. For a couple of minutes I craned my head around and looked out one of the small circular portholes that lined the sides of the aircraft. From this aerial vantage point, I could clearly see what my map had been telling me for weeks, that the Lang Co Bridge was by far the most important bridge in this part of I Corps. One well-placed satchel charge underwater in the main span would have wrecked the bridge and rendered Highway One unusable for a long time. Why did the NVA and VC destroy everything around the Lang Co Bridge, and yet leave it untouched?

For a brief moment, my mind had an answer, but I refused to even consider it until many weeks later, after the impact and implications of the Tet Offensive had become fully evident. That thought was, What if they left the Lang Co Bridge alone because they fully expected to conquer South Vietnam as a result of the Tet Offensive, and they didn’t want to have to bear the expense and difficulty of repairing it themselves? By blowing up lesser bridges and culverts, they had achieved the same goal (disrupting resupply of American and ARVN forces via Highway One), and they could repair those smaller spans in no time at all. My mind refused to consider this, the only rational explanation, because it spelled victory for the VC and NVA and doom for America and our allies in South Vietnam.

I chased those rueful thoughts away as though I were swatting at an unwanted bee buzzing much too close to my mind. I forced myself to concentrate on thoughts of the hot food waiting for us at Phu Bai.

Admittedly, it was not difficult to put this unwanted thought behind me, because, at this point in my Vietnam tour, it was still impossible to consider that America would fail in Southeast Asia. Troop strengths were at their highest peak of the war, over 500,000 strong. Every single significant confrontation with the enemy had been decisively won by American and ARVN forces. To be sure, the VC were a dangerous foe, not to be underestimated, and they used terrifying tactics and crude but deadly weapons. But, from a purely military point of view, the VC were really a joke, sentenced by the American presence and awesome firepower to hiding in the daylight and then sneaking out in the middle of wet, dark, oppressive nights to perform nasty, cowardly acts of violence. The VC were, in our minds, not much of a fighting force, and we had been confidant that they would never engage us in force.

No, this war was all but over, victory was assured, and we would go home, if not heroes, then at least as respected fighters who had done our parts to ensure that democracy would reign in Southeast Asia, and that communist aggression would be contained within the confines of North Vietnam. We would most certainly stop those often-described dominoes from falling at the DMZ.

By now, American military strategists, stung by the surprise and scope of the enemy’s attacks, clearly felt the impact of the Tet Offensive. But because of our isolation at Lang Co, we had little understanding of what was about to happen to us. We would stop in Phu Bai for a couple of days, stock up on food and ammo, and then go north to help 2/5 secure Hue. Piece of cake. It sure beat the hell out of patrolling in the Hoi An area and the Hai Van Pass, where ambushes, booby traps, command-detonated mines and snipers were the rules of the game. At least in Hue we would be fighting the NVA, a more conventional enemy force, where our vastly superior firepower would dominate and take us rapidly to victory.

From my seat in the CH-47,1 had a clear view of the countryside. As we descended into the Phu Bai area, the beauty of Vietnam struck me once again and commanded my immediate attention. If you could just ignore the bomb craters and the defoliation, the mountainous triplecanopy jungles dominating the western approaches to Phu Bai were spectacular, looking more like a travel poster advertising some exotic Club Med resort than a war zone. Vivid expanses of green rice paddies, almost painful to look at because of the brightness of the light emerald sheen that growing rice became, surrounded Phu Bai on its remaining three sides, south, north, and east and stretched as far as I could see from three thousand feet above the landscape.

Vietnam was definitely a paradise. Since my first day “in country,” I had often found myself thinking, Why don’t they stop fighting, build some airports, hotels, and golf courses, and bring in the international tourists? The money they could make from tourism alone would shortly turn them into another Hawaiian Islands. If they would only stop fighting. . . .

Reality rushed in as I felt the CH-47 lose power for its rapid, circular descent into the Phu Bai complex. A few hundred feet above the earth, our pilot pulled back on the reins, and the CH-47’s rotor blades grabbed hold of the air. Our descent slowed rapidly, and then we came to a bumpy stop in another cloud of dust. As the back ramp dropped down, I and about twenty other Marines of Charlie One ran out into the swirling dust, surrounded by the chopper’s chaotic racket. Running out the back hatch of a just-arrived CH-47 helicopter was like running with your eyes wide open into a nasty dust storm. Not smart. Some small, innocuous piece of Vietnamese soil found its way into my left eye almost immediately. Running blindly from the helicopter’s rotor wash, I joined the rest of Charlie One at the edge of the landing zone inside the Phu Bai firebase and blinked the dust out of my eyes.

Phu Bai. Mess hall.

First Sergeant Stanford, Charlie Company’s “top sergeant,” met us at the landing zone and burst our first bubble for the day. The troops would have to make do with their existing “shelter halves,” and the officers would be squeezing into the company’s administrative office, where we had two fewer cots than officers. After being in the bush for well over a month, sleeping on the ground, living more like wild animals than human beings, we had all been looking forward to a cot and a blanket and some hot food. As it turned out this time, being in the rear provided little in the way of creature comforts for the Marines of 1/5.

Top Stanford looked me in the eye as only a Marine first sergeant can and growled, “Sorry, Lieutenant, but that’s the breaks in this man’s Marine Corps. All available shelter has been commandeered, and even though I called in all my markers to get some dry bunks for the men, this was the best I could do. You won’t be here long, anyway.”

“Shit, Top, I know you worked hard and you did the best you could, but isn’t there anything for the men?” I asked.

Top Stanford’s look of disgust was all the answer I got. He changed the subject, “Well, at least the mess hall is still standing, no thanks to Mr. Victor Fucking Charles. A couple of 140-millimeter rockets made a direct hit on the mess hall two days ago, killed a couple of Marines who were in there early cooking up breakfast, and blew away half the damned roof. We convinced the mess sergeant that we would definitely have hot chow, holes in the roof or no holes in the roof. Your platoon is scheduled for a hot meal in about an hour. I’ll let Sergeant Mullan know where Charlie One is to bivouac. Bring your gear up to the company office; you’ll have to draw straws with the other lieutenants to see if you get a cot.”

First Sergeant Stanford was a Marine’s Marine. He had been in the Corps for almost twenty-five years and had seen combat in World War II and the Korean War. He had a lean, tough body and large, hairy forearms. I had seen him do twenty “handstand” pushups once, standing upside down on his hands, pumping his body up and down just for the hell of it. As mentioned earlier, I was always expecting him to pull out a corncob pipe and a can of spinach. He was another enlisted man whom I had to remember not to call “Sir.” The truth was that Top Stanford scared the shit out of me, and I tried really hard never to cross him, even though I (theoretically) outranked him. So, I shut up and told him that Staff Sergeant Mullan would be in on the next chopper with the rest of Charlie One, and I trudged off toward Charlie Company’s administrative office.

Later that morning, I rejoined my platoon outside what was left of the mess hall and lined up at the back of the line, eager to get at the long-awaited hot chow. The mess hall had several large gaping holes in the roof, hastily covered with sheet plastic, the obvious results of being in the impact zone of several 140-mm rockets. It was amazing to me that the mess hall still stood or had not burnt to the ground, and I could not help but wonder what would happen if another 140-mm rocket came down on us right then. It would be poetic justice: damned near starving to death at Lang Co, dreaming of hot chow since we were told we were going back to Phu Bai, finally getting there, and then getting blown away between bites of shit on a shingle.

The officers of Charlie Company met with all the other officers in 1/5 at about 1500 hours that afternoon for a briefing on the mission we were about to undertake, the retaking of the Citadel fortress of Hue. We learned that our sister battalion, 2/5, had been in south Hue since 2 February and had been engaged with the enemy constantly since then. During the briefing, 1/5’s battalion S-3, Maj. L. A. Wunderlich, told us that 2/5 was initially not allowed to use heavy weapons, that they had taken high casualties on the first couple days of the fighting, but that the Marines of 2/5 had persevered. They had finally completed their first sweep of south Hue, only to find out that the NVA had slipped around them and had come in behind them. Consequently, 2/5 had to do it all over again. Before south Hue had been totally secured, 2/5 had been forced to “sweep” the city five times to eliminate all pockets of resistance.

The fighting had been fierce. It was close-in fighting. Going from house to house and without heavy weapons, 2/5 took fearful casualties. After they were finally given permission to use air strikes, artillery, and, ultimately, their tanks and Ontos, naval gunfire, and anything else they could get their hands on, the tide had turned. Casualties had been high, but the enemy was now on the run, and south Hue was considered to be under control.

The job of 1/5 was to pass through 2/5’s positions and cross the Perfume River by landing craft (the huge bridge approaching the Citadel across the Perfume River had been blown up during the night of 31 January, and all traffic north had to go by boat). The 1/5 Marines were then to enter and reoccupy the Citadel, a mile-and-a-half-square fortress that, according to military intelligence, was currently occupied by a couple of reinforced NVA companies.

The briefing was short, no longer than a half hour, and did little to improve my morale. The bottom line was that we would mount up on a truck convoy at “zero dark thirty” the next morning, 11 February 1968. We would be driven as far as possible to the first blown-up bridge on Highway One north of Phu Bai, which prior to 31 January 1968 had crossed a small tributary about two kilometers south of the Perfume River. From there we would hoof it into the MACV (U.S. Military Assistance Command Vietnam) compound in south Hue (which had been nearly overrun during the chaotic night of 31 January) for a final briefing before boarding landing craft for the river crossing and ultimate entry into the Citadel.

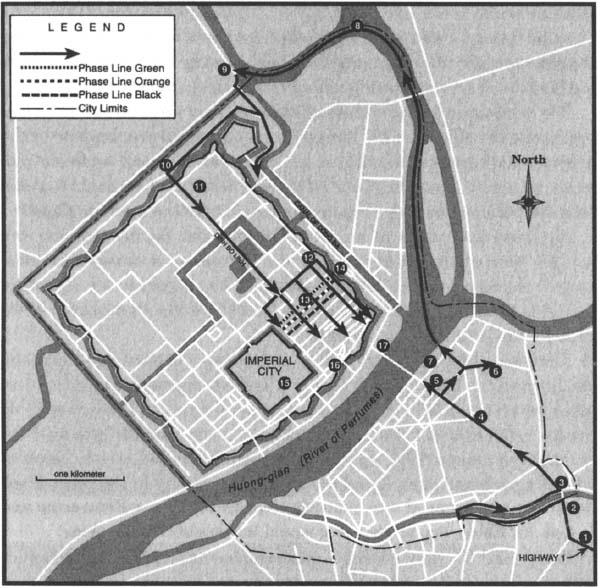

Map reference points: (1) Highway One, the approach route from Phu Bai (approximately eleven kilometers south of this point), 1000 hours, 11 February 1968. (2) Dismounted truck column due to blown bridge, two-kilometer detour. (3) Site of destroyed M-48 tanks, results of fighting involving 2/5. (4) Site of destroyed civilian family. (5) MACV compound. (6) The stadium. (7) The boat ramp area; here, 1/5 departed on Whiskey boats, 0800 hours, 12 February 1968. (8) Site of the Viet Cong sixty-millimeter mortar attack on 1/5, while the battalion was on board Whiskey boats en route to the Citadel. (9) Ferry and boat landing site. (10) 1/5’s entrance into the Citadel. (11) First ARVN Division Headquarters compound. (12) Site of Alpha Company’s first contact with the NVA inside the Citadel. (13) Phase line green, Mai Thuc Loan, 0900 hours, 13 February 1968. (14) Dong Ba Porch (the tower). (15) The Imperial Palace, or City— the sacred inner city within the Citadel. (16) Thuong Tu Porch (the southern tower), 1/5’s exit point from the Citadel. (17) The departure boat ramp area, 1000 hours, 27 February 1968.

The briefing broke up, and we all took off. There was no banter or joking among the officers of 1/5, none of the usual verbal camaraderie or the expected dark humor. We all just left and went by ourselves to our platoons, where we would brief our NCOs and do the best we could to make sure our Marines were as prepared as possible for the upcoming battle.

My mind was blank of independent thought; all my motions and actions were at that moment military, ingrained, necessary, unquestioned. Being a product of my training, I was afraid to let any other thoughts filter in. I found whatever solace there was that dismal afternoon by concentrating on my duties.

I had lost the straw draw and tried to sleep wrapped up in my poncho liner on the hard wooden floor of Charlie Company’s administrative office, which consisted of a GP tent with a wood floor, but I was completely unable to fall asleep. It was, therefore, perversely comforting to hear the sirens go off around 0100, signaling an imminent rocket attack. I took off with my pack and gear, found my platoon’s tent city in the pitch-black darkness, and dropped into a muddy trench with Benny Benware and L. Cpl. Ed Estes, one of the three squad leaders of Charlie One.

Benny and Ed were having a quiet conversation about waterboo, or water buffalo, as they are more accurately and less emotionally named. Waterboo were often the subject of these late-night discussions. Marines were not exactly afraid of waterboo, but they were leery of them. They knew from firsthand experience that most waterboo definitely did not like Marines. No sir, for the young Marines who had to patrol through the paddies and villages of South Vietnam, waterboo were definitely number ten. In Vietnam, if something was good, it was often described as “number one.” If it was bad, it was number ten. It was either good or bad; number one or number ten. There were no shades of in between. Everything that happened was at one extreme or the other.

Benny’s whining complaint was very familiar: “Fucking kids can whack them waterboo over they heads and they don’t give a shit, but let a Marine even look at him, and that fuckin’ waterboo goes damn near crazy. Sheeit, I hate fucking waterboos.” Benny Benware hated water buffalo.

Estes laughed and said, “Shit, Benny, if you’d take a bath more’n once a month, those damned waterboo wouldn’t care about you no more. They think they smell a Missus Waterboo in heat, and they just naturally come down your direction. Then they get really pissed off when they expect to see Missus Waterboo and they get your ugly face. No wonder they get that wild look in their eyes.”

I finally dozed off about 0300, with the sounds of the gloomy banter about waterboo bouncing around in my mind. I came abruptly awake at 0500 hours. The huge, sprawling combat base of Phu Bai was silent. The large “hard point” bunkers, built with huge timbers and many layers of sandbags, stood out in the dim light of the early morning gloom. If there was going to be an attack that day, this was the likely moment. Silence. Stillness. No noises save the minor singing of early morning insects. The sun lightened the eastern sky again over the shattered landscape of South Vietnam.

Thankfully, the rockets never came on that morning.

Although the mess hall was open, all the Charlie One Marines opened C rations and either ate them cold or heated them halfheartedly over a heat tab or two. We were all lost in our thoughts, and none of us wanted to see the half-destroyed mess hall again. I can remember feeling like I couldn’t wait until the truck convoy came to pick us up, so at least I would be doing something, anything, so as to get my mind off of what lay ahead.

Finally, Top Stanford, The Gunny, and Lieutenant Nelson came over from the company HQ hooch and told us where to go to mount up on the trucks. Scott Nelson took me aside and said, “Keep your head down, Charlie One, and don’t ride in the front cab of your truck. There’ve been a bunch of vehicles blown away north of here during the past couple of weeks. An entire ARVN convoy was cut off a few days ago not too far from Hue City, and it was completely wiped out. There are sandbags lining the truck beds, but they don’t do too much good. Get at least one M-60 machine gun into each of your three trucks, and keep your eyes open. You’ll be on point after we dismount by the first blown-up bridge, so let me know if you have any questions about our route.”

I had studied my new maps (each company commander and platoon commander had been issued a brand-new map, a 1:10,000 street map of Hue and the surrounding area, at the battalion briefing the previous day), and I knew from reviewing the map casually the night before where we had to go. So I simply acknowledged Scott Nelson and told him I’d see him at the MACV compound or in hell, whichever came first. It was a poor attempt at humor, something out of a bad movie, but Scott Nelson responded simply with his ever-present grin.

Top Stanford looked in my eyes and said, “Get some, Lieutenant. We owe these bastards.”

After the normal confusion associated with getting an entire battalion of Marines correctly situated on a long line of trucks, the truck convoy slowly departed Phu Bai at about 0700.1 had been on several truck convoys in Vietnam by now, but this was an entirely different experience. Always in the past, when Army or Marine truck convoys went north or south on Highway One, the two-lane dirt road had the usual mix of military and civilian traffic. Whenever we had stopped before, a rowdy group of Vietnamese kids and old ladies would instantly appear to beg for food or generally just to harass us. Now there were no civilian vehicles at all and no traffic coming south toward us whatsoever. Although villages hugged both sides of the highway all the way from Phu Bai to south Hue, some twelve kilometers north of us, no one came out of the villages. It was as though the Vietnamese civilian populace had all died of a sudden, virulent disease. Other than the diesel sounds of our struggling trucks and the occasional sounds of explosions in the distance north of us, the countryside was silent and still. No noise. Bad news. Number fucking ten.

I don’t know how long it took us to traverse the twelve clicks, but I know I didn’t breathe deeply during the entire ride. It seemed like the big six-by trucks that carried us stayed in low gear the entire trip. Since Charlie One was on point for the company, and since Charlie Company was on point for the battalion, I was in the second truck back, with only the lead truck and the mine-detecting engineers in front. And although I had recently started riding in the front cab during trips on truck convoys (having become “salty” before my time and giving more importance to comfort than common sense), I took Scott Nelson’s advice and rode in the back like everyone else. I had seen destroyed truck cabs too often, and it was just too damned quiet right now.

The engineers and the lead truck finally ground to a halt without incident about a hundred meters short of the first blown-up bridge, our “jumping off point.” We stopped at the end of a short line of military trucks and jeeps parked in the roadway. We had been told that there was a makeshift footbridge constructed and that I would decide if we would cross it or go around. Going around meant a two-kilometer detour. We would have to walk about a click to the west, where another bridge crossed this particular river, and then proceed north across the bridge to the other side of the river, resulting in about an hour’s lost time. Adding to our uncertainty, we had no current word on friendlies or enemies in that area.

However, one glance at the supposed footbridge, which was little more than ropes and bamboo suspended by support poles on both sides of the swollen river, convinced me that the two-click detour, even if we had to fight every step of the way, was much more desirable than attempting to cross the dangerous “footbridge.” Any Marine who didn’t make it across the footbridge would undoubtedly drown, as most of us were carrying at least sixty pounds of weapons, radios, packs, and ammunition. So, without hesitation, I called Scott Nelson on Benny’s PRC-25 to give him my assessment. Nelson acknowledged and, without questioning my judgment, approved the detour.

Charlie One dismounted and, with Charlie One Alpha (Estes’s squad) on point, we headed slowly and cautiously west toward the still-intact bridge. It took us more than an hour to make the detour, as we had to proceed slowly. The vegetation along the river was thick; we saw more and more hooches and even some concrete houses. We finally made the bridge without incident, checked it out, determined it to be safe, and moved across. We then started back east along the northern bank of the small but swollen river, which was a tributary of the larger Perfume River.

Signs of fierce street fighting began to appear on the northern side of the river, as we moved back toward Highway One and our jump-off point. The hooches and houses grew gradually into a small business district. Although we couldn’t read the signs, their presence over the buildings indicated that they were stores and shops. Gradually, as two-story buildings began to dominate, we came to the intersection where all the changes in the war during the past few days came into clear, devastating focus.

For over three months I had been walking through the green, rural beauty of South Vietnam. Landscapes that I could have only imagined in dreams had gone by in wave after wave of green paradise. Every imaginable shade of the emerald color had assaulted my senses and had constantly threatened to rip my attention away from the threats of warfare. Vietnam was just simply green and beautiful.

Now, at this unlucky intersection, as I turned finally back onto Highway One, my vision turned to black and white. There was no more “living color.” My eyesight had been suddenly switched to “monochrome viewing only,” with shades of only black, white, and gray. Charlie One had arrived at the edge of the hurricane.