11 February 1968

The street was unnaturally quiet. It was nearly noon, and there was no one in sight on Highway One as far as I could see past my point element. Expecting the worst, but seeing nothing that would give me any reason to slow or delay our progress toward the MACV compound, I kept pace with the point fire team at a ten-meter interval and plodded methodically forward.

Sporadic and now diminishing artillery fire off in the distance to the west gave me some measure of unwarranted comfort again, making me think that perhaps this entire area was now secure, with the remnants of the enemy force on this side of the river being finally chased by 2/5 back into the mountains to our west. But my mind stayed paranoid and would not let me relax: What happens if some of them slipped through 2/5’s lines, as they have already done five times? We could be walking right smack into an ambush. We couldn’t put any flanks out, since they would have to climb over fences and through the large houses that now lined both sides of the road. Oh, well, battalion said this sector is now totally secure, so I’ll just have to take their word for it.

The lieutenant/automaton part of my personality had continued to plod along steadily, and I realized that we had to be getting pretty close to our destination, the MACV compound. As my eyes recaptured their focus on my point element, I realized that our pace had slowed considerably in the past few seconds. The point fire team was still walking forward, but they were moving very slowly now. Their body language gave me no immediate cause for concern, since they hadn’t indicated a hazard ahead of us or some other reason for their slowing. They carried their rifles at a ready position, but not yet in a position that indicated that they were about to fire. And then I looked beyond them and saw what had slowed the point fire team down.

There it was. The Citadel. Even after perusing and pondering the vastness of its two-dimensional image on my 1:10,000 map over the past twenty-four hours, and even though I already knew how huge it had to be, nothing had prepared me for this first three-dimensional view.

Hue’s Citadel fortress was still over a kilometer away, and because of the cluster of two-story buildings sitting at its feet and the homes that lined Highway One on our left flank, only a portion of the Citadel’s actual structure could be seen from our present position. But even from this limited and restricted viewpoint, it was simply awesome. The Citadel dominated all the other buildings in sight with its sheer enormity. The walls of the fortress were at least thirty feet high, but even the walls were made small by the huge tower that stood guard over the one entrance we could see. Battalion intelligence and our new maps had told us that there was a deep water-filled moat totally surrounding the outside walls of the Citadel, and although we couldn’t see the moats from this position, they were easily imagined. I wondered briefly if they had drawbridges like the castles in King Arthur’s era.

Just look at it! My God. The Citadel’s sheer size and immense architecture just kept on going! I still couldn’t see either end of the fortresslike walls, only what appeared to be the southeastern corner. It looked like all the castles I had ever seen in movies and read about in books, all rolled into one. The ancient Vietnamese emperor who built the Citadel must have employed the same architect and builders who had erected the Great Wall of China.

The immense fortress called the Citadel now commanded my entire attention, sitting regally above the comparatively insignificant commercial buildings just across the river. Those commercial buildings were not, in fact, insignificant; they were much larger than the ones we had recently passed through at the site of the destroyed tanks. It was only in comparison with the dominating walls of the Citadel that they appeared to be insignificant.

The imposing aspect of the Citadel was so riveting that I had completely failed to notice the tallest and most imposing bridge I’d seen since arriving in South Vietnam, sitting now totally useless in the middle of the Perfume River, its back broken. A huge expanse of empty space between crumbled concrete supports now allowed the waters of the Perfume to flow by unmolested and unconquered. After a quick double-take between the bridge and the Citadel, the bridge finally captured my attention. Without thinking I gasped out loud, “Number fucking ten! How the hell did they blow that big mutha bridge? That must have taken one hell of a big pile of C-4!”

The main bridge across the Perfume River, one of the largest rivers in I Corps, was now totally destroyed. It had once been a very large and obviously important bridge, since this was the only way for Highway One vehicular traffic to continue north. There was another bridge shown on my 1:10,000 map about a click to the west, but we had been told that it had been blown away years ago. The only other bridge across the Perfume River was a railroad bridge about three clicks further to the west, at the southwestern corner of the Citadel. If this railroad bridge was like any other part of the Vietnamese railway system in northern I Corps, it would also be useless.

The bridge across the Huong Giang River, or River of Perfume, had been a vital link in the resupply chain from the major American I Corps supply depots in Da Nang and Phu Bai to the combat bases in Quang Tri, Dong Ha, Khe Sahn, and the other northern outposts that kept the DMZ reasonably intact. Although this bridge had survived the NVA’s Tet Offensive on the night of 31 January, the attacking NVA had blown the huge concrete and steel bridge away a couple of days later. This occurred after a point element of 2/5 had actually crossed it and had then returned to the south shore of the Perfume after making heavy contact with the NVA on the north side.

It looked as though in its heyday this bridge had supported at least two lanes of traffic in each direction, but it was now completely useless, yet another grotesque “ornament” of the war. Once-proud girders were now a spaghetti of twisted metal, and the main road surface of the bridge was completely broken in half, with a major segment of the bridge’s roadbed now sloping at a near-vertical angle into the jade-green waters of the Perfume River. Whatever explosives had been used for the job had nearly disintegrated one of the reinforced concrete support structures holding the bridge’s span in the center of the river. With one quick glance, it was obvious that the only vehicles going north from this point would be amphibious. Like the bridge at Lang Co, this one could not easily be replaced by a pontoon bridge because of the Perfume River’s width and strong current.

But as amazing and riveting a scene that the sight of this blown-up bridge was, my attention was inevitably and persistently drawn back to the Citadel. The blown-up bridge was just one more piece of visual evidence that the Vietnam War had escalated dramatically on the night of 31 January 1968 and could never again be thought of as a “pastoral guerrilla conflict.” On that long, terrible night, the Vietnam War had graduated into a full-scale conflict that would take America’s full commitment and a large quantity of its tremendous firepower to get back under control.

The Citadel fortress of Hue was our final objective. That’s where 1/5 was heading, across the river and into the Citadel, where we had been told the NVA had overrun and taken control of all but one tiny corner of this massive edifice. Our job was to take it back from the enemy.

Questions, all of them unanswered, swarmed through my mind. How would we get across the river, first of all? Further, if the NVA controlled nearly all of the Citadel, how the hell would we ever get inside, let alone destroy an already-entrenched enemy force? The enemy had now had nearly two weeks since the start of the Tet Offensive to get dug in and ready for our inevitable assault. If they controlled all the towers and therefore all the fortress’s entry points, this was going to be one hell of a fight just getting inside the damned thing!

As these questions crowded my uneasy mind, my eyes focused again on the Citadel’s entry-point tower. It was massive, at least fifty feet high and thirty feet square, made of the same large, reddish brown bricks as the walls. The tower appeared honeycombed with fighting positions, which would easily provide excellent cover for a couple of squads of fighting men by itself. I felt that if the fifty-one men of Charlie One occupied that tower and the adjacent wall, we could hold off an enemy force several times our size virtually indefinitely, given the beans, bullets, and Band-Aids that any fighting unit required to keep fighting.

As my survey of the tower continued, I noticed something that had previously escaped my attention. There was a large, red flag flying on top of the tower, and now that my eyesight finally focused on the flag, my blood ran cold and my entire body raised instant goose bumps. It was a flag, all right. It was big, it was bright red, and it had a yellow star in the center. It was the flag of the NVA.

The enemy was here, right across the river, and they were taunting us, waving their flag in our faces, saying that they were in there and that now the tables were turned. The enemy was no longer the hunted, no longer an elusive but deadly prey. The gods of war had wickedly changed the rules. The NVA had taken a great prize, and it looked like they intended to keep their prize for a long, long time. If we wanted them out of there, we could just come right on ahead and try our best to evict them, and the gods of war would decide who would prevail.

Without realizing that I was speaking just above a stage whisper, I started to tell Benny Benware to radio Staff Sergeant Mullan, who was still with our rear element, to come up and join me. As I began speaking, I was surprised and a little embarrassed to hear that I was whispering, so I cleared my throat, pretending like I had a frog, and forced myself to speak loudly and clearly, emulating our instructors in Quantico who had continuously emphasized the need for the command presence, to be an effective Marine Officer. Benny immediately made the radio call and told me that Sergeant Mullan had acknowledged and was on his way. It was my excuse to tear my eyesight away from the dominating presence of the Citadel, and I turned around and surveyed the trailing elements of Charlie One as I waited for “Mother” Mullan to arrive.

In referring to Staff Sergeant Mullan in conversation with my troops, I never used his well-earned nickname, because it would violate several command dictums that we had learned in Quantico. According to tradition and protocol, a marine officer should never refer to any other Marine by his first name. In Vietnam, officers and NCOs commonly referred to their troops by their last names only, simply because it was faster to say “Estes” than it was to say “Lance Corporal Estes.” Enlisted men were sometimes referred to by nicknames, such as “Benny” or “Chief” (which seemed to be the nickname for every Marine I ever met who had even a small portion of Native American ancestry). But staff NCOs and officers were always referred to with both rank and last name or, in a pinch, just by their rank.

The chain of command, and the respect that the Marine Corps demanded for both rank and the chain of command, had been drummed into me for nearly two years, as it had been to every other Marine, enlisted and officers alike. Thus, it was Sergeant Mullan, and Lieutenant Warr, and Major Wunderlich, and Private Lattimer. No, I never referred to Sergeant Mullan as Mother Mullan, or Mutha Mullan, but I definitely thought of him in both those ways.

The nickname “Mother” Mullan was well earned, because SSgt. John A. Mullan definitely took his job as platoon sergeant of Charlie One very seriously. After fourteen years in the Marine Corps, Sergeant Mullan loved his men and his Corps, and he took all aspects of his job seriously, although not without a great sense of humor. Every man in Charlie One respected him and followed his orders to the T and jumped when he yelled, “Jump.” And it wasn’t just because they had to. In Vietnam, especially in a combat situation, you could not depend 100 percent on blind faith in the military system of obedience and courtesy. Experienced bush Marines did not instantly give their undying obedience to staff NCOs and officers, just because of their higher rank. During the Vietnam era, that respect had to be earned. Although this was not spoken of universally among the ranks, it was prevalent, and I believe it was accepted and understood as a significant but minor refinement of the rules made necessary by the shattering realities of combat in Vietnam.

In the Vietnam War, there were too many occurrences of new NCOs and officers, fresh from stateside training and ignorant of the realities of combat in the rice paddies and jungles of Vietnam, getting people needlessly hurt or killed because they took themselves too seriously and failed to listen to the experienced hands. The “rumor mill” made sure that everyone knew about these incidents. Each new NCO or officer arriving in Vietnam for the first time had to show that he had his act together before most experienced bush Marines would follow him and obey his orders blindly and instantly. The Marines’ respect for the chain of command, one of several important aspects of Marine training that had made them legendary, now had to be earned by each new small unit commander that entered the fray in I Corps. In most cases, if a new Marine NCO or officer was considered potentially dangerous because of his conditioned belief in the conventional tactics he had been trained to use, yet he was likable, the experienced Marines of lesser ranks had subtle but effective methods to perform the required “on-the-job training.”

“Mother” Mullan was taller than the average infantry Marine. Around my height of six foot two, Sergeant Mullan was of medium build and could hold his own physically with most younger Marines in the platoon. Although quiet by nature, he could be very loud when necessary. God protect the Marine who screwed up within Mother Mullan’s areas of responsibility. When he was riled, his long, drooping mustache, slightly outside Marine Corps regulations but not uncommon in Vietnam, would start twitching, and he would unconsciously pull one corner of it into his mouth while his light blue eyes would narrow and sparkle dangerously. He never had to revert to physical threats or even violence, as I understood sometimes occurred (although it was never tolerated) between staff NCOs and enlisted men in the Marine Corps. All he had to do to straighten out any Charlie One Marine who had the temerity or bad luck to screw up was to give that poor hapless soul the “jaundiced eyeball” that staff NCOs are so good at and let loose with a few selected motivating words and phrases.

The men of Charlie One, almost to a man, loved Sergeant Mullan as they loved their own mothers, although if you suggested that to any of them you would want to get into the next county really quickly. Furthermore, Sergeant Mullan, like the classic Marine staff NCO that he was, loved the Marines of Charlie One and took care of them in ways that even the finest of America’s mothers could not measure up to. That they sometimes referred to him sarcastically and somewhat fearfully as “Mutha Mullan” was understandable and was probably the result of feeling his wrath. But even when they castigated him, it was with much respect.

Mother Mullan very seldom said anything to me in greeting in situations like this. He just walked up to me and looked me in the eye, a slight grin of acknowledgment and confidence on his face, and I knew that he was ready to take on anything I could assign him. One of the first rules learned upon arriving in Vietnam is that saluting officers is verboten, especially outside the wire (outside the protective defenses of a combat base). VC and NVA had sniper scopes, too.

I quietly gave Sergeant Mullan some quick and probably unnecessary instructions to keep the men alert and ready for anything and to take over while I went into the MACV compound and checked in. As I turned to enter the compound, I observed once again that Mother Mullan didn’t have to speak to make men move. He just did his version of a Sawaya survey, gazing in each squad leader’s direction with his “jaundiced eyeball” expression, and the men of Charlie One reacted instantly, taking up firing positions with whatever cover was available. Highway One quickly became the dusty, empty center of an elongated perimeter of Marines ready to fight. Confident that Charlie One was in good hands, I turned away and entered the MACV compound.

The MACV compound was an old two- or three-story hotel reinforced by stacks and rows of sandbags and many strands of barbed wire. It was the last building on the east side of Highway One and was just two hundred meters from the entrance to the destroyed bridge. From my vantage point just outside the sandbagged entrance to the compound, I could easily see the Perfume River, and the bridge that could no longer perform its duties. On the river’s south shore just to the east of the bridge, I saw what looked like a very busy, hastily prepared boat docking area. Obviously, bulldozers had scraped away any vegetation that had lined the edge of the river to allow boats to load and unload their cargoes.

There were a few Vietnamese sampans hovering just offshore, but there was no room for them to dock. Several U.S. Navy LCMs, or “Mike boats,” the middle-sized landing craft associated with the landing forces of the Marine Corps since late in World War II, were dominating the rudimentary docking area. Landing craft were not new to us. As a trainee in Camp Pendleton and again in Quantico while going through Basic School, I had participated in amphibious warfare exercises and had hit the beach with forty-nine other second lieutenants just south of Virginia Beach early one morning from the ramp of a Mike boat.

There were two other types of landing craft used by Marines. The small Poppa boat was the original landing craft that appeared during the height of the Pacific War after the Marines learned the hard way that the Higgins boat was more trouble than it was worth. The Higgins had no convenient front ramp to protect its passengers from small-arms fire until it dropped down to become the bridge from the boat to the (theoretically) dry shoreline. As passengers on the Higgins boat, the World War II Marines were offered little protection from enemy small-arms fire, because the Higgins boat was made mostly out of wood. And there was no front ramp, so that when a Higgins boat ended its journey on an enemy-held shoreline, its occupants had to crawl over its sides, into the sometimes shallow, sometimes deep water at the shoreline.

The Poppa boat and its larger sibling, the Mike boat, were a great improvement over the Higgins boat. About twenty Marines could squeeze into a Poppa boat, while the much larger Mike boat could handle about fifty combat-ready Marines. The steel construction of these improved modes of combat transportation provided much more protection; their large, powerful diesel engines could often push the bow of the landing craft right up onto the beach, and the front ramp would then drop down, allowing easy egress onto the beach. At least, this was usually the case. A few times during the South Pacific island-hopping campaigns, the designated landing beaches did not cooperate, and their protective coral reefs prevented the landing craft from making it all the way to the beach. The Navy personnel had no choice but to drop their ramps and watch as the Marines assaulted into chest-high water several hundred meters from the shoreline. But still, these boats were great improvements over the Higgins boat.

The third in this family of amphibious warfare landing craft was called the LCU, or landing craft utility. The Navy personnel referred to them as Whiskey boats. Perhaps they were a more current version of the LCU, or LCW. (The word “Whiskey” is used in the military alphabet.) Although I had not yet laid eyes on one personally, I had heard a few things about these craft. According to the rumor mill, a Whiskey boat made a Mike boat look like a rowboat by comparison.

Amid the confusion of the Mike boats clustered around the Perfume River’s chaotic shoreline, two Whiskey boats stood, ramps down, disgorging a stream of supplies carried by a motley group of Marines. The Whiskey boats were huge. It looked as though we could get the entire company on board and have room left over. The crew of Marines tending to the Whiskey boats’ hoard of much-needed supplies were scurrying like ants between a huge pile of ammunition and other supplies stacked up above the high-water mark and the boats. Several pallets of C rations had been off-loaded from the Whiskey boats and were stacked neatly side-by-side next to the more deadly supplies. Still somewhat affected by our shortage of food at Lang Co, I found this a comforting sight. At least we’re going to have chow for a while, even if it was only C rats, I thought. The Gunny will be happy.

The scene was made unusual and captivating by the obviously frenetic pace of the platoon of Marines off-loading the supplies, and for a moment I mused that they must have been engaged in a race of some sort. Normally, Marines assigned the duty of carrying any mound of supplies from one point to another resembled reluctant, two-legged mules with helmets instead of ears. Their progress was usually steady (especially when the jaundiced eyeballs of their gunny or their platoon sergeants were within range), but there was nearly always much complaining about the unfairness of not only having to face danger and death fighting for their country, but having to do the work of beasts as well. This time, although I was within easy hearing distance of the work, I could tell that no one had any time to bitch. These men were nearly running back and forth between the Whiskey boats and the temporary supply dump, each with a case of small-arms ammo or mortar rounds or some other form of death.

I was about to ask myself why they were in such a hurry when the NVA manning the Citadel’s tower across the river made my question superfluous. A single shot from an AK-47 rang out loudly, and the working party hit the deck. Someone screamed, “Sniper, sniper! Get down, get your heads down!” Another frantic voice out shouted this alert with, “Where the fuck did that one come from? Is it still those assholes on the tower?”

After a few seconds went by and there were no following shots, the work party started to move quickly again, and I decided that I didn’t want to ask too many more questions. Without choice, my mind asked another, inevitable question: I wonder how long this has been going on? That made it easier to tear myself away from the action and to go into the MACV compound.

As I stepped into the MACV compound’s sandbagged entryway, I was blinded for a few moments as my eyes slowly adjusted to the gloomy light typical of an American command bunker in Vietnam. Command bunkers in Vietnam were often dug into the ground several feet and then covered with three or four feet of timbers, metal runway sections, and layer after layer of sandbags, the Marine’s constant companion. This one was inside a building that could have once been a large home or a small hotel. The main part of the working areas were at ground level, but there appeared to be a second, perhaps even a third floor. The inside walls were all reinforced by a layer or two of sandbags, and the entryway was double-reinforced by sandbags. Walking into command bunkers always left me with a vaguely claustrophobic feeling, like I was crawling inside a cave.

Of course, a command bunker’s size, permanency, and resources were in strict proportion to the command group that they contained. Divisional command bunkers were near-duplicates of stateside “puzzle palaces,” with a myriad of communications devices, status boards, and tactical maps dominating the decor. Regimental and then battalion command bunkers were scaled-down versions of this theme, with their size somehow always matching their position in the chain of command. Company and platoon command bunkers were most often hastily prepared, offering little in the way of shelter or resources.

Yet regardless of their size and importance, command bunkers all had some things in common. The plastic-covered tactical maps critical to command and communications at every level were the most obvious similarity; one or more Prick-25 radios and other larger, more powerful communications devices took up nearly every square inch of available desk space. The strange breed of men who filled the airwaves with their constant, absolutely necessary babble of information took up most of the sitting spaces. And the darkness. There were no windows in command bunkers, for obvious reasons, so even during the brightest hours of the day, command bunkers were smoke-filled dungeons making even those with the best vision strain their eyes to see every detail.

The other thing that all command bunkers had in common was that they were either totally becalmed with bored silence sporadically stirred gently with a quiet situation report or request for supplies coming in over the radio network from a subordinate unit, or they were a place of shattering chaos. When one or more field units were in contact with the enemy, the bored silence of command bunkers quickly deteriorated into a nightmare of tension, frantic cries for help in the form of fire missions or medevac requests, or requests for reinforcements, resupply, or reaction/maneuver forces to help them get back into control of their situation.

The MACV compound matched the image of the normal command bunker in every way. At this particular moment, it was quiet, although there were probably twenty people inside its gloomy walls. After walking further inside the sandbagged room that served as the main command and control point for the MACV in Hue, I began picking up bits of quiet conversations between radio operators and each other, and between the officers. These officers had the job of making the decisions that would keep them and the American and South Vietnamese forces firmly in control of the conflict now raging out of control throughout South Vietnam.

The dim, smoky light gave the brightly colored arrows, boxes, rectangles, and other assorted symbols on the maps a muted, fluorescent hue. These symbols indicated the locations of enemy units, friendly positions, and suspected avenues of attack. I easily recognized the baseball-diamond-shaped Citadel fortress in the center of the large wall map that immediately grabbed the attention of any person who entered the room. None of the occupants of the command center had yet noticed my entry, so I had a few moments to study the map, to see if I could learn anything about what we were up against.

Most symbols that represented military units inside the Citadel itself were one color, red. Red was the color reserved for enemy positions. There were several red symbols crowded inside most of the Citadel, and one black symbol, alone by itself in the northeast corner of the diamond-shaped Citadel. I was already aware, from the briefing we were given in Phu Bai on the previous day, that this symbol represented the headquarters group of the First ARVN Division and some infantry units who were providing security for them. There sure as hell were a lot of red symbols on the tactical map, both inside and outside that damned Citadel. After nearly two weeks of constant fighting with large elements of a previously elusive enemy, the Viet Cong and the NVA still had a stranglehold on the Hue area. There was little comfort in the black symbols that now dominated south Hue, because my eyes were forced back to the blotches of red. How many of them were there waiting for us inside Hue’s Citadel fortress?

As these questions crowded my mind with the fears and uncertainties that had constantly been present since my arrival in Vietnam, I noticed someone break away from the group of Marine and Army officers deep in discussion and map-gazing and head in my direction. I quickly recognized him to be Maj. L. A. Wunderlich, 1/5’s battalion S-3, or operations officer. Major Wunderlich had been our S-3 and effectively third in command (after the battalion commander and executive officer) of 1/5 since I had arrived in country, and I had experienced several brief but confidence-building encounters with him. Major Wunderlich always seemed to remain calm, no matter how difficult the present crisis; he had a great strategic and tactical mind. The Marines and officers of 1/5 liked him a lot, and we were all expecting him to take over as the new battalion commander, since our last CO was killed a few days before in Phu Loc 6. Although the battalion executive officer, Maj. P. A. Wilson, was technically second in command, as the battalion S-3, Major Wunderlich was the de facto second in command of the forward elements of 1/5.

Major Wunderlich had the same relaxed, almost bored expression he always carried around. Only the much-deepened bags under his eyes displayed the stress weighing down on his shoulders since I had first met him in Hoi An. In the four or five weeks between 1/5’s move to Phu Loc 6 on Christmas Day 1967 and the night of the Tet Offensive, 1/5 had undergone the new command of, and then the loss of, two new battalion commanders.

I greeted Major Wunderlich in the required traditional manner (Marines do not wear any “cover” while indoors, and we do not salute without a cover, or hat, on, unlike our Army brethren) by simply coming to attention as he approached. He responded in his normal, quiet but strong voice, with a small, amused smile on his face. “How are you doing, Charlie One? Keeping your head down?”

I tried to shake off the persistent nagging fears and questions about the impending operation and forced as much confidence into my manner and voice as possible. “Just fine, sir. Charlie One is the point platoon for the battalion, and we were instructed to make contact with you here and then await further orders. My men are strung out down the street. I had Benny contact Charlie Six Actual and let him know that we’re here, and he should be up here pretty soon, sir.” I had never been able to develop the knack of being, or even acting, totally calm when addressing someone two or more grades higher in rank than me.

Major Wunderlich replied, “OK, Lieutenant. Go ahead on back out there with your people and tell them to keep spread out and to keep their fool heads down, hear? I’ll fill Lieutenant Nelson in on the scoop when he gets here. But thanks for letting me know that you’re here; I feel safer already.” I wasn’t sure if he was serious, or if he was mocking my attempt to be militarily proper.

“Aye, aye, sir. Major Wunderlich?” I knew I’d been dismissed, but I couldn’t help asking just one more question.

“Yes, Lieutenant Warr?” was his wistful reply.

“Sir, are you taking over 1/5 permanently this time, sir? The men are all speculating that they will let you take over as skipper, sir. We all feel pretty comfortable with you running the show.” This was the major topic of scuttlebutt in the rumor mill, and the odds were heavily in favor of Wunderlich, a very senior major who had been with 1/5 for many months, taking over as battalion commander.

Wunderlich cast me a weary glance and said, “No, Lieutenant. 1/5 has a new skipper. He joined us this morning. You’ll be meeting him down by the loading ramps later.”

I persisted, asking, “Down by the loading ramps, sir? What’s the colonel’s name, sir? Do we know him?” Discretion was never one of my strong points.

Major Wunderlich replied, “Uh, he’s not a lieutenant colonel quite yet, although he’s up for the promotion right now. His name is Major Robert Thompson.”

Continuing in my no-thought mode, I asked further, “Major Thompson, sir? I don’t recall a Major Thompson in any of the other battalions’ S-3 slots. Is he new in-country?” I tried hard to keep any of the constantly present fear out of my voice. Breaking in a new battalion commander could be very hazardous to the health of the troops, especially if this was his first combat experience in Vietnam.

“No, Lieutenant,” Major Wunderlich subtly emphasized my rank as a gentle reminder of just exactly who I was. “He’s not new in-country. He’s been the Fifth Marine’s Regimental S-4 for several months.” Wunderlich was beginning, obviously, to tire of this conversation.

I couldn’t stop. The bald edge of fear egged me on. “S-4, sir? You mean he’s the regimental supply officer, sir?” I had not at all intended for my voice to crack when I said the word “supply.” Nor had I considered for even a moment that everyone else in the bunker would stop their tense, whispered conversations to breathe a collective breath. But it happened, as it had happened that time in my Junior English class when I had tried to silently squeeze out a persistent fart. Just as I thought that the gas would pass without notice, everyone in the room stopped talking and my attempt at stealthy gas-passing failed miserably. Most of my high school classmates had burst into loud and long raucous laughter at what became mildly famous at Marshfield High School in Coos Bay, Oregon, as “Warr’s Salvo.” Now, however, the gallows-humor laughter was stifled. Most of the Marines and Army personnel in the bunker were experienced in combat. They could thus immediately identify with my reaction to this information, that 1/5 would go into combat with a brand-new commanding officer who was a supply officer. Flashing looks of fatalism crossed the few sets of eyes visible in the gloom.

Major Wunderlich was less amused. “Lieutenant Warr, must you be reminded that we are all trained to be infantry officers first in the Marine Corps? That no matter what our particular assignment may be, that being an infantry officer is our number-one priority in any situation that dictates it?” From my present position at point-blank range, Wunderlich’s quiet but firm voice slashed me unmercifully, but fortunately, the others in the room were oblivious to, or ignoring, my dressing down as he continued his tongue lashing. “Major Thompson is going to need 125 percent effort and confidence from everyone, especially from someone in your position. I don’t want to hear another comment or question of that sort again. You understand me, Mister?”

I reflexively came to attention and said, “No, sir. I mean, yes, sir. I mean, aye, aye, sir.” Clumsily, hastily, I began a tactical withdrawal and started edging toward the door and freedom. Like a brand new “boot” Marine, I erroneously but instinctively saluted Major Wunderlich while “uncovered,” breaking a long-standing Marine Corps tradition and acting like just any other dog-face soldier. Then, of course, realizing my error and now attracting the attention of everyone in the MACV command post, I made a bad situation worse by tripping over my feet as I turned abruptly and nearly lost my balance. I barely recovered and stumbled, red-faced, back out into the gray morning.

Although the sun was mostly blocked by the persistent overcast, the daylight momentarily blinded me as I emerged from the MACV compound, the low sounds of quiet, bitter laughter completing my humiliation. It still didn’t matter much. The single dominant thought in my mind at that moment, and one that ruled my thoughts continuously through the days and weeks ahead, was that 1/5 was now in the hands of a logistics officer. Now, I don’t want to belittle the importance of supply or logistics, because this is obviously a critical aspect of successful military campaigns. However, S-4s were usually people who wanted to be in logistics, and not necessarily in command. Further, Major Thompson might have been the most exemplary officer in the history of the Marine Corps, but if he was an S-4, chances are that he had little or no combat experience, specifically little or no infantry combat experience. As I continued to think about it, however, I realized that fact was not rare. The United States had not fought a significant war since the end of the Korean conflict fourteen years previously. One result of that happy fact turned out to be usually unhappy for junior officers, NCOs, and enlisted men in the Vietnam War. It meant that their company and battalion commanders usually had no combat experience. It took between four and six years to reach the rank of captain, then another four to six years to be promoted to major, and then another six to ten to achieve the rank of lieutenant colonel. This meant that the average lieutenant colonel or senior major, like Majors Thompson and Wunderlich, had been commissioned after 1954 and thus had little or no combat experience. This situation did not sit well with combat Marines who knew too well the realities of the battlefield in Vietnam.

These unsettling thoughts vaporized as the image of 1st Lt. Scott Nelson and The Gunny came into focus, my eyes finally adjusting to the gray gloom once again. It was immediately obvious that the company CP group was all there, obvious because of the cluster of “whip antennae” that surrounded Nelson and The Gunny as they approached the MACV compound. There were three fifteen-foot-high antennae, indicating that the Charlie Company radio, Travis Curd’s FO radio, and a forward air controller’s radio were dueling for the airspace over Scott Nelson’s head. They really do look like aiming stakes, as we often labeled them, using the pervasive black humor of Vietnam. I had to be careful with that name around Benny, though, because he would go into a black funk if you referred to his whip antenna as an aiming stake. Benny in a black funk was not to be tolerated.

As usual, Scott Nelson had his map in one hand and the phonelike radio receiver of his command PRC-25 in the other, holding it gingerly to his right ear. He looked, for just a moment, like an overgrown child using a telephone for the first time in his life. As he approached the entry to the MACV: compound, tucking the map packet back into the left leg pocket of his Marine Corps-issue utility trousers, he flashed his patented, boyish grin briefly in my direction and then concentrated on finishing his radio conversation.

“Roger, Millhouse Six, I’m at the MACV compound now. I’ll make contact with Millhouse Three and await orders. Charlie Six Actual, out.” The Prick-25 squawked a distant, “Millhouse Six, out,” and went dead in Nelson’s ear. Nelson slowly pulled the phone out of his ear, continued to listen for just a moment longer, seemingly reluctant to believe that his new experience with a telephone was over, then gave up, handed the handset to his radio operator, and directed his solid frame toward me and the MACV compound. More than anything else, Nelson resembled a football player, probably a center, breaking eagerly away from the huddle, ready to kick some ass and take some names. Nelson was eager to get on with the game, to get his hands on the ball.

“How are you, Charlie One?” Nelson asked.

“Er, just fine, Skipper.” I needed to be elsewhere, or I would begin to compulsively confess my faux pas of a few minutes past. I decided on the spur of the moment to take a chance on Major Wunderlich’s being too busy to mention my unfortunate choice of words when learning about our new battalion commander, and kept my mouth shut.

Nelson said, “Okay, Charlie One. Just make sure your people keep their heads down out here. It’s kinda quiet around here.”

“Aye, aye, sir,” I replied. I was still not quite comfortable with Nelson as our company commander. I didn’t like calling him “Skipper,” as Marine company commanders were often called. The title “Skipper” was earned, not automatic. I didn’t like Nelson’s habit of using my radio call sign, Charlie One, when he was talking to me face to face. It seemed like he couldn’t get out of the “command radio voice mode” that had been drilled into all of us during our long months of OCS and Basic School at Quantico.

Still grinning at everything in general, Nelson finally tore his gaze away from the southwestern wall of the Citadel and ducked into the MACV compound. He had obviously seen the NVA flag flying defiantly above the Citadel walls, but he had refrained from commenting upon the view. Charlie Company would now receive our marching orders into the Citadel fortress of Hue. Now we would find out just how long that crimson symbol of the enemy’s defiance would continue flying over the Citadel.

The Marines of First Platoon, Charlie Company, First Battalion, Fifth Marines, at the Phu Loc 6 firebase. This snapshot was taken a couple of days before the NVA started their mortar and rocket attacks on the combat base. January 1968. Pfc. Robert Lattimer is on the far left of the front row, kneeling. SSgt. John Mullan is kneeling, in the center, fifth from the left. L. Cpl. Ed Estes is standing behind SSgt. Mullan, dressed in a dark green sweatshirt. Ed’s friend and Marine buddy Charles Morgan is standing fifth from the left. Charlie One radio operator Benny Benwaring is standing between them, (author photo)

1/5’s combat base at Phu Loc 6, early January 1968. Tent City, just before the trenching and burrowing began in earnest, (author photo)

The author’s OCS graduation picture. Quantico, Virginia. March, 1967. (author photo)

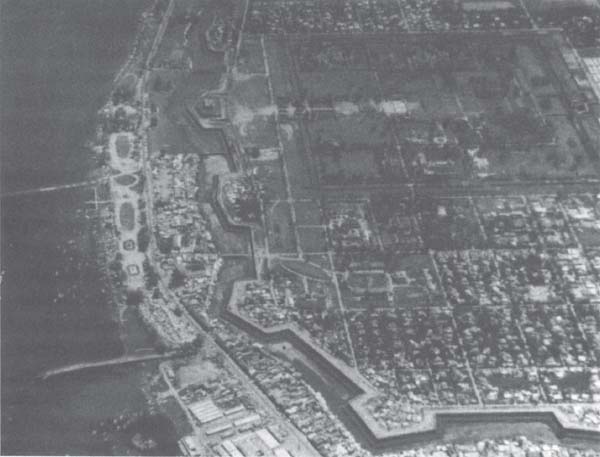

Aerial view of the southeast corner of the Citadel fortress of Hue. This photo was taken sometime after the NVA destroyed the main Highway One bridge, which is clearly seen in the lower left-hand corner of the photo. The Imperial Palace, the “inner fortress” of the Citadel, is also clearly seen in the upper right-hand corner. Most of the fighting inside the Citadel’s geometrically shaped outer walls took place in the residential district directly below the Imperial Palace, lower right-hand corner of the photo. (U.S. Marine Corps photo)

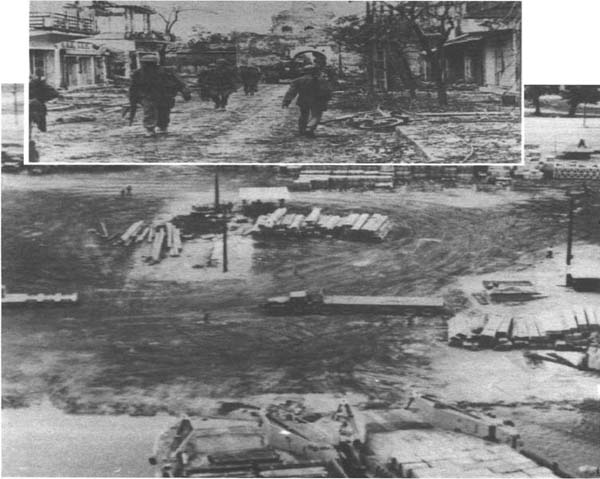

Photograph taken by (then) Major Thompson, depicting 1/5 Marines aboard a Navy Mike 8 boat. I believe that this “Mike 8” boat was actually what I call a “Whiskey” boat, or what the Navy calls an LCU. The very wide gunwales of this boat and the extremely large load also indicate that this was an LCU. It doesn’t matter; these are 1/5 Marines advancing by landing craft toward their objective: the Citadel fortress of Hue. (U.S. Marine Corps photo)

I believe that this is a Delta Company Marine, near the crest of the Dong Ba Tower, the scene of some of the bloodiest fighting inside the Citadel. The extended wall of the Citadel can be seen clearly in the upper right-hand section of the photo, and it is obviously much lower than the rubble on the tower. (UPI/Corbis-Bettmann photo)

Marines of D Company, 1/5. The infamous Dong Ba Porch, or Dong Ba Tower, stands out clearly in the background. This photo was taken after the fighting was over in this area, which is evidenced by the severe battle damage to the tower and the fact that these Marines are standing around in the open. (U.S. Marine Corps photo)

The ramp at Hue, June 1967. (U.S. Naval Historical Center photo)

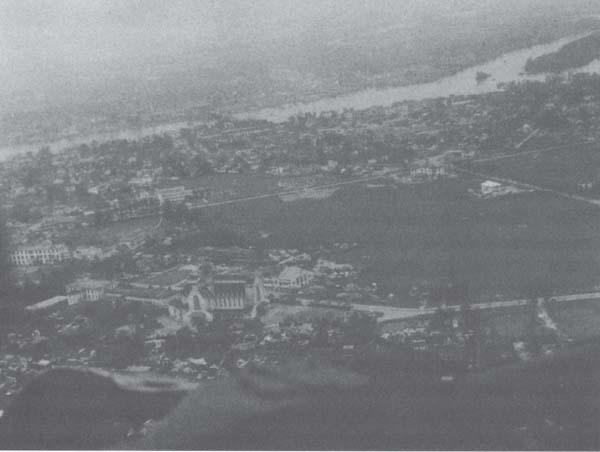

An aerial view of the Hue Citadel airstrip looking north. (U.S. Marine Corps photo)

An aerial view of the Old Imperial City of Hue as seen from the doorway of a helicopter. (U.S. Marine Corps photo)