2 Leadership Then . . . and Now

Reflections on Leadership

It is truly exhilarating to be at a stage at which one has time to reflect on one’s career and to identify the takeaways from the time spent in progressively responsible leadership roles along the way. To reach the heart of leadership, one needs to engage in deep reflection and to ask oneself some soul-searching questions at each stage along one’s leadership trajectory, rather than waiting until the end of one’s career. By doing this systematically, one has the opportunity to reflect, take stock, devise a plan, formulate corrective actions, and make improvements, as required. These questions for reflection should include the following:

Questions for Self-Analysis and Reflection

- What are the reasons I chose to seek out progressively responsible leadership positions?

- Was I propelled by causes outside of myself, or was I motivated by self-interest?

- Was I as magnanimous as I could possibly have been along the way?

- Did I listen to my inner radar and follow my inner compass?

- Was I bound by moral and ethical imperatives?

- Did I practice what I preached?

- Did I address the major sources of ambivalence and surprise?

- Did I pay attention to the opinions, needs, and aspirations of those expected to do the daily work?

- Did my organization and the morale of employees thrive under my leadership?

- Did I communicate widely and work with the widest possible cross-section of people to embed key leadership beliefs, values, goals, and expectations into the fabric of the organization?

- Did I co-opt, train, and support future leaders with the skills required to sustain and build upon the gains?

At critical points in one’s career, there is a need to engage in introspection and reflection—a soul-searching borne out of a desire for assurance that there was congruence among knowledge, beliefs, values, motivations, and behaviors. The need for a convergence of values and behaviors is a leadership imperative that unearths all that one has stood for and fought for over the years. This exercise also highlights the practices that can be discarded and elucidates the ones that must be kept alive. And for those who spend their lives in search of truth, genuineness, and fidelity to longstanding universal values, the answers can make a difference in the way one assesses the success of one’s career.

The insights gained from this exercise will also affect the sense of contentment that one hopes to achieve in retirement, when one inevitably will have time to look back and think deeply about one’s actions and achievements. It also influences the ability to arrive at a conclusion as to whether or not one has fought a good fight, achieved the desired outcomes, and demonstrated the character and personal attributes that a leader could only hope would be his or her leadership legacy.

Leaders today must have a strong determination to ensure that they contribute to their sense of satisfaction that they did, indeed, work hard to demonstrate the personal attributes they say they value most. These include integrity, empathy, courage, optimism, and respect.

Among these attributes, demonstrating respect is the most fundamental and all-encompassing if one wants to reach the heart of leadership. Based on what we know about the qualities that have a lasting impact on organizational cultures and on people’s lives, respect should include respect for self, others, cultural differences, diversity, and human rights, to name a few. These are fundamental to and form the basis of healthy, effective, and productive relationships in any setting—be it the home, the workplace, or the community—and with all individuals—our children, relatives, friends, or professional colleagues. More than ever, leaders today require a deeply held conviction that respect is the sine qua non in effective interpersonal relationships.

The way we treat people along our leadership journey can eventually enhance or hinder our career progression and upward mobility. Examples abound of leaders who failed because they did not demonstrate these interpersonal competencies. Moreover, people do not easily forget how they were treated; when they are treated poorly, it remains with them and affects them for a long time.

In some jurisdictions, before anyone is promoted to a leadership role, those who will eventually make the decision conduct site visits and hold interviews with individuals with whom the aspiring candidate worked in earlier positions. The questions asked at these site visits are geared toward unearthing the behaviors the aspirant demonstrated in those settings. Respect for others, especially those at the lower rungs of the organizational hierarchy, is always included in this probing exercise. Why? Because demonstrating respect for others is a competence that is at the heart of leadership.

I remember quite vividly an example of a situation where key community members believed that a principal did not show respect for her community in terms of their values, their beliefs, and their expectations of the school. I had to intervene after giving the principal ample support and leeway to put the relationship back on track. Eventually, the principal had no choice but to resign. Trust, once lost, is almost impossible to regain. It takes inordinate effort to redress such situations. This all started with what the community described as a lack of recognition and respect for their deeply held values and a principal who, they felt, was either unwilling or unable to turn the situation around.

Admittedly, there are times when a leader must challenge the values of a community if these values are inhumane or inconsistent with organization values. If one encounters a situation, for example, in which there are deep-seated biases and prejudices, unfair behavior, or disrespect shown toward individuals and groups, a leader must take a stand, responding quickly and decisively. But any leader who chooses to take on the community or other groups of individuals must recognize the strength, stamina, and support from one’s supervisors and colleagues that is required when one becomes embroiled in such conflicts.

Nonetheless, in all such situations one must always be guided by a strong sense of moral imperative and the need to act according to one’s conscience.

Martin Luther King Jr. provides some insights on this theme. He once said,

On some positions, cowardice asks the question, is it expedient? And then expedience comes along and asks the question, is it politic? Vanity asks the question, is it popular? Conscience asks the question, is it right? There comes a time when one must take the position that is neither safe nor politic nor popular, but he must do it because conscience tells him it is right.

This civil rights icon was alluding to our modern notion of moral imperative. Many educators today use this term regularly to describe their motivation in making decisions in schools. Often, we use this to test actions related to the life chances of students and their role in ensuring that their actions can withstand the highest test—is this the right course of action in this situation?

Deep introspection helps leaders reflect on the leadership lessons learned and insights gained over time. Because these lessons represent the seeds they have sown and determine the reputation that remains throughout their career and lifetime, it is important for leaders to think deeply about the impact they are having on the people they serve, their colleagues, and the organizations they lead.

When I was a secondary school vice principal, I had very high expectations of staff—similar to those I had for myself. My main motivation was to get things done quickly for the benefit of students. My popular refrain was “the children cannot wait.” I felt that their time in school was finite and that we should not waste it in any way. Things had to be done with a sense of urgency in order to achieve the outcomes that we had established for the students. In that situation, what I wanted was to have all staff members involved with students outside of their regular teaching duties. This meant that teachers were being asked to assume some form of extracurricular activities to support student engagement and well-being.

One of the oldest members of the staff—someone close to retirement—came to my office to see me. He told me that he couldn’t do any more than he was currently doing because his wife was very ill and he was having serious problems with his teenage son. I was so touched with his sincerity and pain that I began to cry. I remember vividly my reflections at the moment. I thought to myself,

Here you are, thinking you are a cracker-jack vice principal, always talking about how important empathy is, how empathetic you are, and how much you care about people. But you were not being considerate of the needs of all your staff members in this case! You were more interested in getting things done than considering the needs of the people who are expected to do the work.

Through deep introspection, I decided that it was necessary to change my behavior in a manner that was more consistent with the values I espoused and openly expressed on many occasions. In other words, I knew I had to work harder at practicing what I was preaching. This incident was a catalyst in my career—a watershed moment. I became more self-aware and more vigilant, and monitored more closely how I behaved toward the people I supervised. It was a life lesson learned that stayed with me throughout my career as a leader. This incident and the accompanying takeaways also had implications for relationships in other contexts.

I once again reflected on Tom Sergiovanni’s notion of the morality inherent in relationships when there is unequal distribution of power, articulated in his book Value-Added Leadership (1990). As a young administrator, I took this very seriously. In fact, this became a mantra throughout the years I spent in educational leadership. Within the organizations in which I worked, I recognized the “power” and the responsibility that accompanied the positions I had. I also sought out the rich body of research that exists in the educational literature on the topic of “position power.”

Having position power means that it is incumbent upon leaders to use the power that accompanies leadership roles wisely and ethically. How a leader treats the custodians, the secretaries, the clerks in the finance department, or the mom or dad from the poorest part of the community matters significantly! It is so easy for leaders to treat people differentially in terms of the respect and attention shown to them, based on a host of factors if leaders do not have the values-driven, people-oriented inner radar that helps monitor their behavior. Biases and prejudices that we have all picked up along the way can surreptitiously undermine our best intentions. They can greatly influence the behavior of even those leaders who consider themselves to be fair-minded individuals who have acknowledged, and continue to work on, dislodging their own biases and prejudices.

Self-knowledge and awareness are enhanced when leaders take the time to think critically about their role, decisions, intentions, motivations, and modus operandi. Most important, it would serve leaders well to think long and hard about the meaning of power, privilege, and entitlement in their own lives and how they use this when they are entrusted with positions of added responsibility. This awareness, when acted upon, can be a source for either leadership success or dismal failure in the role when it is underdeveloped.

On the question of how leaders use power, which was mentioned earlier, it is important for leaders to reject the “power over” mentality in their pronouncements about who they are when describing their leadership style. Over the years, I have seen the impact that this type of leadership has had and the havoc it has inflicted on people’s lives, sense of well-being, and job satisfaction. On the other hand, when leaders understand themselves and what having real power means, they eschew negative notions of power and adopt more positive approaches. They see power as working with and through people to get things done and to realize their goals. They take seriously how they lead and reflect on issues such as what it takes to motivate and inspire people so that they can realize their full potential and contribute to the collective success.

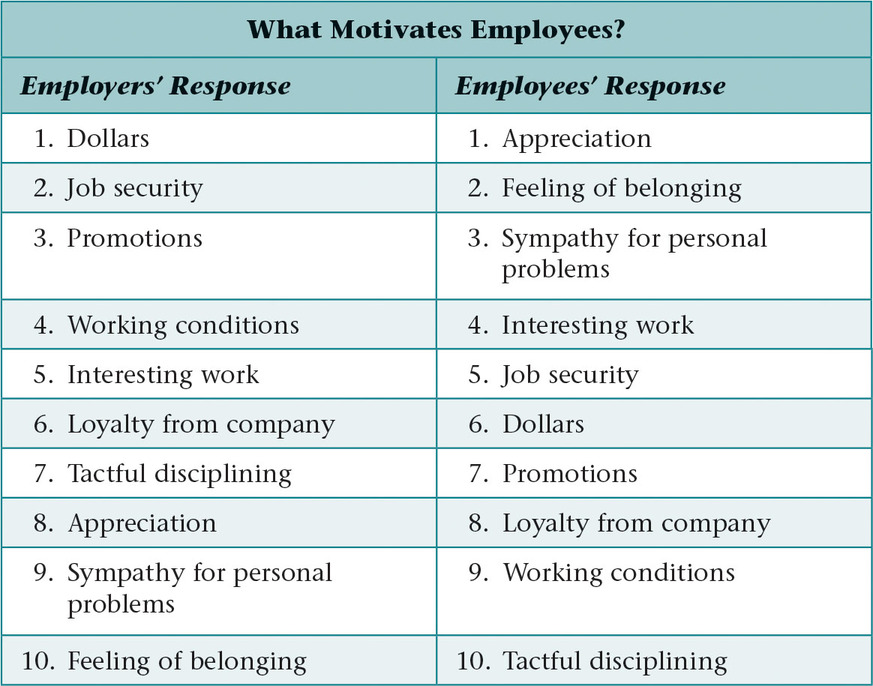

On the question of what motivates people, there are many lessons to be learned from the work of Kovach (1987), who asked employers and employees to rank order some key variables to answer the question “What motivates employees?” What is most instructive is the difference between the responses:

The top three variables for employers—dollars, job security, and promotions—are consistent with the perspectives of some of today’s leaders in relation to their employees. It is worth comparing these with the top three variables chosen by employees—namely, appreciation, a feeling of belonging, and sympathy for personal problems.

What Motivates Employees the Most?

Appreciation

When I was a superintendent of schools, many principals shared their feelings with me from time to time on how much they valued being told that their work was appreciated and that a supervisor valued qualities such as their commitment to students and work ethic. Direct, specific, meaningful, and genuine feedback motivated them to do even more and to be better at what they did. Their comments included popular sayings such as “You can catch bees with honey—not vinegar!” These were confident, successful adults! One could be so easily tempted to think that they did not need to be affirmed and validated. But another lesson that we can all learn is that even the most confident and successful employees thrive on being validated by their supervisors. There is almost a human need for reaffirmation—especially from those who have the responsibility to evaluate performance or to determine one’s promotion.

Feeling of Belonging

The second on this list—a feeling of belonging—should not be underestimated, either. A workplace that has this ethos is also one that has lower turnover rates. People want to be there. There is a sense of collegiality—a notion that goes beyond congeniality. Sergiovanni (1990) used these terms and made distinctions between them years ago. More recently, others, such as Jasper (2014), have made similar observations. Where true collegiality exists, people are highly motivated to work toward common goals and outcomes.

Kathleen Jasper (2014) also makes a distinction between congeniality and collegiality and highlighted the effects of these qualities on organizations as follows:

- Congenial is [being] friendly, good-natured and hospitable. Congeniality is a decent attribute for an organization to have—people are nice to each other and staff is compliant. However, a good-natured, compliant staff does not necessarily yield increased creativity or productivity. In addition, friendly, congenial systems are sometimes a façade distinguishing a hierarchal structure where most of the decisions are made using a top-down approach. . . .

- Collegial on the other hand means shared, mutual and interrelated; decisions are made together and responsibility is communal. It’s more than being friendly; it’s getting work done in an effective way as a team by identifying opportunities for improvement and solving problems together. Collegiality is often a catalyst for difficult conversations, contention and even conflict to take place. Ultimately, collegiality is essential for impactful work to transpire.

More recent work on professional learning communities (PLCs) has highlighted the difference between congeniality and collegiality. My own observation is that the change in behaviors of those engaged in PLCs over the years has been phenomenal. In the early years, when there wasn’t a deep understanding of how PLCs operate at their best, there were superficial notions of what successful PLCs looked like. People falsely equated “noise” with a real desire to solve problems related to the school. Consequently, they did not ensure that improvement was the primary reason for these gatherings. There has, however, been a discernible difference in how PLCs are functioning today. Educators have expanded their ideas about PLCs with the research that has been available in recent years. As noted above, PLCs can have a real impact when collegiality is at its best.

Sympathy for Personal Problems

The third variable ranked by employees is “sympathy for personal problems.” Employees do not leave their problems at home or at the front gate of the school. The issues that they are facing at home or in the community are always with them. Only a few individuals can simply shake off problems, do their jobs, and pick up later from where they left off the previous day. Their concerns on and off the job can affect their interactions with their colleagues and students.

I remember working with a principal who suggested to staff that they should leave their problems behind and not take them into his school. His unwillingness to see staff members in their multiple roles—as coaches, parents, religious leaders, or community members—reflected his lack of a strong people orientation in the workplace. Not surprisingly, he was neither liked nor respected. People would not go to him if they had personal problems.

Being attuned to the personal problems of staff can help aspiring and seasoned leaders alike see people in the totality of their human character, qualities, values, aspirations, and world views. It also helps them suspend judgment when problems or conflicts arise. Asking the custodian about her sick child, taking a first-period class for a teacher who had a dental appointment, or covering for the school secretary who is going through a divorce can make a difference in the culture of the school and the relationships that are forged. It is in small ways that we demonstrate our humanity, caring, and concern for others in the workplace. And instead of using the term “sympathy” for personal problems, I would make a slight change to take this idea to a new level by describing this variable as “empathy for personal problems.”

Empathy: A Quintessential Leadership Competence

The ability to be empathetic has profound implications for the way we engage one another at an interpersonal level. It is the quintessential human characteristic—one that demonstrates genuineness and loyalty and engenders a strong sense of connection with people. Empathy describes the feeling or reaction that most people welcome, especially when they are having problems.

In his recent book, The Formative Five: Fostering Grit, Empathy, and Other Success Skills Every Student Needs, Thomas Hoerr (2017) discusses recent research on empathy and makes a persuasive case for the importance of empathy in human endeavors. He rightly makes a distinction between empathy and sympathy, stating that we can sympathize with the plights of others without fully understanding, appreciating, or empathizing with their unique perspectives.

He starts his discussion with empathy because, in his own words,

As I have grown older, I have come to value its importance more and more. When I think about the qualities I want in work colleagues, I realize that kindness and care are at the top of the list. Of course, knowledge, skills and work ethic are incredibly important, but I spend a lot of time and invest a great deal of emotional energy at work, so I want to be able to trust and lean on the people around me. (Hoerr, 2017, p. 36)

Hoerr refers to the centrality of empathy in teaching, its importance as a business attribute, and the fact that there is enough of it to go around when we practice this skill. He emphasizes that relationships are destined to fail in its absence. He states that history has taught us that a mass lack of empathy can lead to mass cruelty and the tendency to divide people into “us” and “them,” which can lead to suspicion, miscommunication, and conflict. Not surprisingly, he states that bullying, a problem being addressed in many school districts today because of its long-lasting consequences, results from a lack of empathy. He acknowledges that it is human nature to “retreat to our tribe and to feel most comfortable among those who look, act, and think like us” (Hoerr, 2017).

He also offers six basic steps and a few strategies for developing empathy, as we teach this skill to our students in the same way we approach teaching other skills. These steps include the following:

- Listening

- Understanding

- Internalizing

- Projecting

- Planning

- Intervening

How to Take Action for Developing Empathy

Hoer (2017) offers concrete actions to develop empathy.

For all teachers:

- Help students recognize and understand the perspectives of others.

- Help students engage in service learning.

- Help students appreciate their own backgrounds and biases.

- Create safe spaces for students to tell their stories.

- Consciously teach about stereotypes and discrimination, the history and evolution of attitudes, and the reasons why people’s degrees of empathy toward different people vary.

- Help students examine historical examples of innocent people who were wrongly accused of crimes.

- Always encourage students to consider situations from a variety of perspectives.

- Assign books that feature a diversity of humanity.

- Create a system by which students can submit anonymous compliments for specific classmates.

- Get students involved in charitable causes.

For middle and high school teachers:

- Teach students about the differences in perspective between journalism and literature and between current and historical accounts.

- Involve speakers who can give “the story behind the headlines.”

- Read portions of Paul Theroux’s book Deep South (2015) with students to examine a slice of life with which they may not be familiar.

- Draw content from Material World: A Global Family Portrait (1995) by Peter Menzel and Charles Mann.

For elementary school teachers:

- Teach students the difference between sympathy and empathy.

- Use empathy as a tool to help students understand character creation and development in fiction.

- Use games and competitions to help students see situations from others’ perspectives.

- Ask students to speculate as to what other children might like to receive for their birthdays—discounting what they might want for themselves.

- If a student’s pet dies, use the occasion to talk about feelings.

For principals:

- Make it a priority to hire teachers who are empathetic toward all kinds of students—not just those who excel in school and are well-behaved.

- Work to help teachers appreciate their students’ home and community environments.

- Sponsor special thematic events, such as “Empathy Night.”

- Create a social action committee among faculty to help students (and possibly parents) make a difference in the community.

- Screen books on topics such as empathy for discussion with colleagues and students.

- Form a voluntary faculty book group to read books related to empathy.

As an educator, I cannot emphasize enough how careful one must be in selecting books for use in schools. It is not about censorship, as some will say. It is about ensuring that the same students do not have to spend their entire careers feeling that they, and the groups to which they belong, are never presented in a positive light. As a superintendent of schools, I have been called by students who are crying and asking if they have to remain in classes in which they are presented in a negative light. What is unfortunate is that these groups never have the opportunity to see themselves or their groups presented positively.

Teachers and principals are encouraged to make sure that students and their backgrounds are presented positively and that students have avenues to share their thoughts and feelings about the content of the curriculum and its impact on them. It is important to acknowledge that there is a serious problem when students and their backgrounds are consistently portrayed negatively in the books to which they are exposed in the classroom. If students and their cultures are never portrayed positively, there is a great imbalance in what they will take away. So many students from diverse backgrounds have complained over the years about the negative impact of how they are portrayed. It is important for teachers and school leaders to see this as an unfairness for students in general, and for students from minority backgrounds in particular. So often, when I expressed the complaints of many students and parents, the response was, “These are the classics!” My response was, “The classics for whom?”

I was very impressed with education in New Zealand when I served as adviser to the minister of education. One of the tenets of the curriculum at the time should serve as a lesson to all of us: “The curriculum should not alienate the students.”

I hasten to admit that in recent years I have met many teachers and principals who are attuned to these issues and are making every effort to ensure that their schools are implementing equitable and inclusive education practices. In fact, in Ontario, for example, we have developed many documents to address this and other equity issues. Once such document is Realizing the Promise of Diversity: Ontario’s Equity and Inclusive Education Strategy (2009), available at www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/policyfunding/equity.pdf.

This award-winning document, which is being implemented in Ontario schools, was designed to make concrete suggestions and provide opportunities for all students to reach their fullest potential. The document acknowledges that publicly funded education is the cornerstone of democracy, preparing students for their role in society as engaged, productive, and responsible citizens. It recognizes that some groups of students, including recent immigrants, children from low-income families, aboriginal students, boys, and students with special education needs, among others, may be at risk of lower achievement if concerted efforts are not taken to address these issues. The document lays out a clear vision for equity and asserts that excellence and equity must go hand in hand. They are, by no means, diametrically opposed. Instead, they are two sides of the same coin at least, and often on the same continuum, at best. The document emphasizes the fact that an equitable and inclusive education system is fundamental in realizing high levels of student achievement and is central in creating a cohesive society and a strong economy to secure Ontario’s future prosperity.

Framed within the context of the province’s Human Rights Code, this strategy envisions an education system in which

- All students, parents, and other members of the school community are welcomed and respected.

- Every student is supported and inspired to succeed in a culture of high expectations for learning.

Early in my leadership career, I developed and taught a course for leaders. It was called “Human Relations in Education.” I was motivated by the fact that the leaders whom I considered to be effective all possessed a constellation of skills that are now being described in business and other fields as “people skills” or interpersonal competencies. What was interesting at the time was that there was so much focus in principal training programs on emphasizing operational skills—budgets, timetabling, staffing, and plant operations, among others. Admittedly, every aspiring leader should have at least a baseline knowledge of operational functions. My contention is that these tasks were being emphasized at the exclusion of the skills that I felt, from experience, were required to be effective leaders of people and to transform organizations, among other important goals.

It was not surprising that some of the individuals who failed miserably as principals or superintendents or in business could perform operational duties very well. But their Achilles’ heel was their inability to lead and work effectively with people.

My experience in education tells me that both skill sets are needed if organizations are to function effectively. The issue is that we should not hide behind the operational duties, because these are not the ones that take organizations to new levels of attainment. It is through people and capacity building that we are able to move organizations to the apex or pinnacle of performance and greater levels of achievement.

Teaching human relations and interpersonal competencies must become an essential component of leadership development programs.

Leadership: A Brief Historical Overview

When taken seriously, leadership does present its challenges. But those who aspire and prepare to assume leadership roles do recognize that it will not be easy. So, they fortify themselves to deal with the eventualities. For all leaders, this means not engaging in self-pity when times get rough. It doesn’t take long to learn that it is important to be tough and resilient and to develop a thick skin. But that toughness in leadership should not be of the “muscle-flexing” kind. It has to be a principled toughness, based on core values.

A longstanding conundrum for leaders is whether or not good leaders show emotions. Tom Sergiovanni (1990) posited that showing outrage, for example, is an acceptable emotion for leaders. This was a very important lesson for me, because I had always heard that leaders in general, and women in particular, should never show emotions. People who showed emotions were considered to be unsuitable for leadership. And no one, especially a woman aspiring to leadership at the time, wanted to appear to be weak. That was certainly “career limiting,” as it was often described.

This was validated in the early years of the “women in educational leadership” movement. Many of us were cautioned against showing negative emotions—especially anger. Some women certainly thought that they would never move up the organizational ladder if they did not comply. Even today, in many circles, the prevailing notion is that good leaders are never emotional.

Being emotional, especially when referring to women, is still viewed as a sign of weakness. In those prior days, it was particularly difficult for women who were thought to be too emotional to move up the leadership ladder. So many struggled with how they would be viewed if they allowed any emotion to become visible. But for me, Sergiovanni provided new ways of looking at this issue at the time. He made a convincing case that outrage is totally acceptable when important values are infringed upon. This resonated with me. It was one of the most liberating insights that I have had as an educational leader. It gave me permission to express outrage and to express it openly when deeply held universal values were compromised. Of course, with such behaviors, it always hinges on the question of how one expresses outrage or other emotions that are perceived as negative.

One answer lies in the ability to engage in constructive confrontation, which I learned through guidance and counseling courses and through assertiveness training. Being able to confront constructively means that it is never acceptable to express negative feelings at the expense of others. The language used is never intended to offend—to make ourselves feel good while putting others down. And although the term “confront” has such negative connotations, it is simply an invitation to others to see and appreciate the impact that their behavior is having on you or on others. Being able to confront constructively is an important interpersonal competency for all leaders.

Historically, we have seen debates in the literature on what exactly leadership means and how it is manifested. In the 1950s and 1960s, the great-person or trait approach to leadership suggested that leaders had a finite number of identifiable qualities—for example, charisma or integrity—which could be used to differentiate successful from unsuccessful leaders.

Later, the study of leaders concentrated on how leaders behaved—what they did, rather than how they appeared to others. This new focus gained popularity during the 1970s with the recognition that individual traits were significantly influenced by varying situations. This was described as situational leadership. However, many would say that the greatest failure of this approach was that it did not explain fully what leaders did, what they achieved, or the outcomes they forged.

A third categorization of leadership, contingency leadership, emerged in order to address the shortcomings of situational leadership. It is the view of Roueche, Baker, and Rose (1989) that among these perspectives, the notion of contingency leadership was the most comprehensive view of leadership at the time. They asserted,

Underlying this approach is the idea that, to be effective, the leader must cause the internal functioning of the organization to be consistent with the demands of the organizational mission, technology or external environment, and to meet the needs of its various groups and members.

A major lesson that I have learned over the years is the fact that leaders must pay attention to, and seek to address, the needs of the people they lead. It is not unusual to see leaders booted out of office because they ignore people’s needs or their sincere feedback on the directions that are being taken. Leaders who are self-absorbed often interpret this as criticism rather than valuable input for improvement. It sometimes seems as if leaders forget the people who elected or chose them in the first place. Still others forget the promises they made when they were actively seeking office. At the same time, I am by no means naive. People’s needs and expectations change. Sometimes the demands are unachievable. The expectations may be inconsistent with one’s values, out of step with the times, or incompatible with the philosophy and directions of the organization.

A case in point was in the early years when we fought to bring more women into administration. This was after many years of having leadership roles dominated by men, even though the profession was predominantly female. A few bold leaders sought to reverse this trend.

A vivid memory was a situation in which I worked as a young superintendent in a community described by many as conservative. At that time, many community members fought for the right to have input into who their principal would be. In this particular district, one of the demands was that they wanted a male principal. These were the early days of the women’s movement in society in general, and in the educational arena in particular. But communities were not yet sensitized to these human rights issues. It took a lot of time to convince the members that we could not discriminate in this way. We also knew that if we sent a woman into that setting, she would have to overcome inordinate obstacles. We were able to convince the community about the superior qualifications and competence of the woman who was placed in that setting, and provided ongoing support for her transition. The following year, our criteria were carefully developed, with the caveat that it would not be appropriate to include the gender of the principal as one of the criteria for selection.

What Is Leadership Today?

Leadership is about making others better as a result of your presence and making sure that the impact lasts in your absence.

—The Compelled Educator, September 2014

Leadership is being bold enough to have vision and humble enough to recognize achieving it will take the efforts of many people—people who are most fulfilled when they share their gifts and talents, rather than just work. Leaders create that culture, serve that greater good and let others soar.

—Kathy Heasley, founder and president, Heasley & Partners (as cited in Helmrich, 2016)

We have spent half of our lives learning how to do, and teaching other people how to do. But we know in the end it is the quality and character of the leader that determines the performance—the results.

—Francis Hesselbein, former CEO of Girl Scouts of the USA (as cited in Chism, 2016)

Leadership is about making others better as a result of your presence and making sure that impact lasts in your absence.

—Sheryl Sandberg (2013)

Words like “direct” and “control” in early definitions of leadership reflect the authoritarianism of many leaders in the 1950s and 1960s. In the 1970s, situational leadership was the model style. In the l980s and l990s, terms such as “systems approach,” “management by objectives,” “participatory leadership,” “transformational leadership,” and “empowerment” became prevalent in the leadership literature. What we have also seen, with the progression of time, is a more humane, people-oriented, and human resources development approach to leadership and organizational improvement. Many leaders today recognize the importance of issues such as motivation in determining job satisfaction and productivity.

Admittedly, there are times when leaders must act authoritatively. Certain powers and authority are often given to leaders under our various acts, statutes, regulations, and strategic planning directions. A certain degree of accountability accompanies those responsibilities. But leaders today and in the future must have within their repertoire the leadership behaviors that engage people. They must become “enablers” creating conditions for employees to thrive and to do their best work. They must be able to develop the alliances and coalitions necessary to support their organizational goals. They must be able to work effectively with people to achieve the desired goals.

My image of the leader is one who has the competencies to motivate, inspire, and develop people. These leaders model positive character attributes. They are passionate about student achievement and the capacity building of staff. It is an image of a humane individual who provides strong advocacy to make the system work for the benefit of students and community. It is an individual who has within his or her repertoire an abundance of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) skills that enables him or her to arrive at win-win solutions when conflict arises. It is an image of responsive, dynamic, courageous, and optimistic leadership—one that eschews self-interest and is always thinking of what is in the interest of the common good.

As stated earlier, leadership requires a great deal of self-awareness, reflection, and analysis. The need for this orientation and related competencies cannot be overstated. It means that leaders must get in touch with their beliefs about human nature, because these beliefs affect profoundly one’s leadership and management style. It means engaging in constant self-assessment to identify strengths, weaknesses, and areas that need improvement. By paying attention to these requirements, leaders set themselves on a pathway to achieving the highest levels of competence and professionalism.

The nature of leadership has also changed dramatically over the years. The cries for improved outcomes, higher standards, and increased accountability have become a worldwide phenomenon. Ever-expanding demands and expectations have placed new requirements on the role of the school leader. Within this milieu, many harken back to the words of Michael Fullan in his seminal book, What’s Worth Fighting For in the Principalship? (1989). The following quote was a major source of inspiration for me as a young leader and continues to resonate in all aspects of leadership. Recognizing that we have the power to influence decisions and outcomes if we take action ourselves, rather than waiting on others to act, is a life lesson for those who aspire to be effective leaders:

Counting on oneself for a good cause in a highly interactive organization is the key to fundamental organizational change. People change organizations. The starting point is not a system change, or change in those around us, but taking action ourselves. The challenge is to improve education in the only way it can be—through the day-to-day actions of empowered individuals. This is what’s worth fighting for in the school principalship. (Fullan, 1989)

Michael Fullan expresses this imperative extremely well. The challenge is a timeless one with the potential for creating an enduring impact. It applies to leadership in all forums, in all settings, and at all stages along the career lifespan. It reinforces the importance of taking action ourselves to achieve desired results.

Reaching the Heart of Leadership: Key Requirements

In thinking about the content of this book, I have decided to focus on four leadership lessons that I have learned over almost forty years in education and the pivotal impact of these lessons on my thinking and leadership. Reducing this number to four was extremely difficult, as I have learned so many lessons across my professional lifespan.

I will describe briefly each of these lessons learned, review the literature on related research, and discuss some implications for leadership. These lessons are by no means unique to my experience. Leaders in both private- and public-sector institutions will attest to the fact that, when they consider their core business, many of the insights and experiences apply to themselves and their organizations as well. For that reason, I will assert that certain leadership qualities and practices can be found in all organizations. Most of the required competencies are also generalizable across occupational domains. In education, they must be in place if we are to reach the heart of leadership.

Reaching the heart of leadership therefore requires

- Self-knowledge and awareness;

- High expectations for learning and achievement;

- Holistic education: character, career, the arts, entrepreneurship; and

- Capacity building for system, school, and professional improvement.

Lessons Learned

- Reaching the heart requires deep reflection and introspection about who we are and what we plan to achieve to ensure that our values and actions are aligned.

- Respect is fundamental to healthy, effective, and productive relationships. It is one of the most important skills for us to demonstrate in the workplace.

- It is necessary for leaders to find out what motivates their employees so that there is congruence between management expectations and employee understanding.

- Empathy is the quintessential characteristic of human relationships. The ability to demonstrate this skill must be taught in leadership development programs.

- Awareness of the difference between congeniality and collegiality as one’s modus operandi in the workplace is essential for leaders. The former is necessary, but not sufficient. The latter can made a significant difference in achieving personal and organizational goals.

- Human relations and interpersonal competency development are essential for aspiring and future leaders because of the pivotal role that these skills play in leadership effectiveness.

- Conducting site visits to ask questions and compile a rounded picture of the attitudes and performance of aspiring leaders is a good way of balancing what people say in an interview and how they perform on their job—and, even more important, how they relate to people, especially those who are on the lower rungs of organizational ladders.

- A clear understanding of issues such as power in general, and position power in particular, is critical for future leaders who need to be able to recognize the impact of their behavior on employees.

Action Steps for Developing Empathy

- Establish a climate of respect, collaboration, high expectations, and good-will.

- Provide ongoing professional learning opportunities for staff to increase self-knowledge and the importance of being reflective practitioners.

- Help leaders and students learn motivation theory and seek to understand more fully the motivations behind the important decisions that are made.

- Provide human relations and interpersonal competency training for staff and students.

- Embed a strong human rights orientation in all policies, programs, and practices.

- Review equity and inclusive education programs to encourage a strong social justice, fairness, and action orientation.

- Implement leadership development programs for individuals at key stages along the leadership continuum.

- Encourage future leaders to learn about their community by seeking out opportunities to become involved in outreach and engagement initiatives.

- Develop partnerships with businesses, social agencies, community leaders, and politicians to strengthen school-community relationships.

- Work with staff to ensure that their policies and practices best serve the needs of students.

- Demonstrate continuous improvement in student learning, achievement, and well-being.

- Learn about and address, within financial constraints, the reasonable expectations of community groups.

- Work with parents, school councils, school districts, and other leaders to build consensus on the attributes that they want to have in their future leaders.