Nikos Kazantzakis: Raking Stones

‘What is our duty? To struggle so that a small flower will blossom …

Nikos Kazantzakis, The Saviors of God

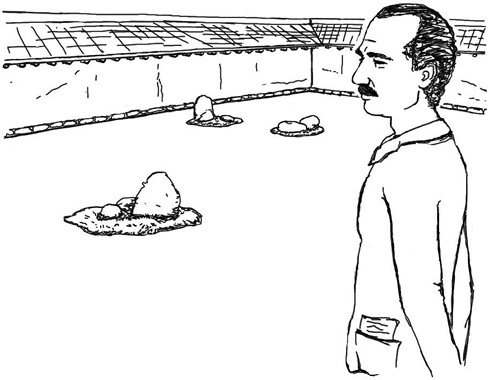

The wiry, middle-aged man stands squinting at stones. Dressed in sensible grey slacks, sweat-stained shirt and jacket, Nikos Kazantzakis looks like an accountant on holiday in Japan. But the Greek poet, novelist and playwright, author of the brilliant Zorba the Greek (the eponymous hero later played by Anthony Quinn), is doing fieldwork. He has been wandering for years like this—Paris, Berlin, Italy, Spain and Russia—echoing the hero of his epic poem, The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel. ‘Though life’s an empty shade’, screams Odysseus, ‘I’ll cram it full of earth and air, of virtue, joy, and bitterness!’ Now, in the spring of 1935, Kazanzakis is still stuffing himself full with life: click-clacking clogs, sixteenth-century screens and alleys of stone lanterns. ‘If only I could lift up all of Japan’, he writes to his wife Eleni, back in Greece, ‘and bring it to you and wrap it around your shoulders like a kimono’.

But Kazantzakis does not sail home. He stands, rooted to the spot in Kyoto’s Ryoan-ji Buddhist temple, staring at a karesansui, or rock garden. An austere, walled rectangle measuring a modest 10 metres by 25 metres, it houses fifteen irregular rocks, placed asymmetrically in clusters on ‘islands’ of moss. Surrounding these is a ‘sea’ of pebbles, raked daily into ripples. Tapering walls give the impression of a larger space, as does the garden’s use of negative space; the tiny oblong seems vast. While it borrows scenery from behind the walls—a trick known as shakkei in Japanese—the garden’s only visible life is the moss. Everything else is dead, dry stone. Kazantzakis is captivated. ‘I wander through this garden’, he writes, ‘and vague desires are gradually illuminated around me, crystallizing around a hard core’.

He finds beauty in the garden’s austerity: its stark lines, its contrasts of moss and rock, and the undulating waves of the stones. But it also moves him because, in the karesansui’s stones, he sees an idealised portrait of himself. ‘If I were to form my heart in the shape of a garden’, he wrote in his travel book Japan China, ‘I would make it like the rock garden’.

For all his travel exhaustion, Kazantzakis was not trying to suggest his mind was dead—that he was paralysed with exhaustion or anaesthesia. On the contrary: the rock garden left him energised. What he recognised in the karesansui was a metaphysical principle known as élan vital, or ‘vital force’, an idea he took chiefly from philosopher Henri Bergson, with whom he studied in Paris.

In Creative Evolution, Bergson compared the élan vital to military shells bursting into pieces, which themselves burst into pieces, and so on, forever. The fireworks show was without aim, purpose, plan: a restless, inventive principle of change. Bergson’s was a so-called ‘process’ philosophy, part of a tradition that included the ancient Greek thinkers Heraclitus (‘no man can step into the same river twice’) and Cratylus, alongside modern scholars such as Friedrich Nietzsche and Alfred North Whitehead. For process philosophers, the basic metaphysical category is not being, but becoming: activity, dynamism, movement.

Kazantzakis took this basic principle and made it into a philosophical and artistic credo—what emerged from the ‘form of his heart’, as he contemplated the rock garden. In his literary works, he portrayed life as a continuing dialectical movement, beginning with the most primordial matter or instincts, and ending with freedom and death—and then beginning again. For example, in his book of spiritual exercises, The Saviors of God, Kazantzakis described mankind’s progress from childish egotism to recognition of family, race and humanity, then beyond humanity to all life and the cosmos as a whole. ‘The universe is warm, beloved, familiar’, he wrote of this stage, ‘and it smells like my own body’. This movement, from mute impulses to meditative unity, was echoed in Kazantzakis’ modern Odyssey, his magnum opus, and the book for which he hoped to be remembered. Over the course of the poem, Odysseus moves from bestial violence and carnality to noble militarism, to intellectual reflection, to ascetic serenity, to a sagelike welcoming of death. Having wandered, like his author, from Europe to the Middle East, and then to Africa, Odysseus dies willingly in the bleak white of Antarctica. Kazantzakis describes Odysseus’ dying mind as a flame—a metaphor for pure consciousness, without physicality. And in this flame, all of Odysseus’ memories live on for a moment more:

As a low lantern’s flame flicks in its final blaze

then leaps above its shrivelled wick and mounts aloft,

brimming with light, and soars toward Death with dazzling joy,

so did his fierce soul leap before it vanished in air.

The fire of memory blazed and flung long tongues of flame,

and each flame formed a face, each took a voice and called

till all life gathered in his throat and staved off Death;

In this way, Odysseus climbs another rung of Kazantzakis’ metaphysical ladder, and is united with his world. As flame, he incorporates all things into himself, and has developed beyond self and other, subject and object, and other commonsense distinctions (the entire concluding chapter of the Odyssey is dedicated to this philosophical climax).

But this realisation is not the end of Kazantzakis’ philosophical development. Like Odysseus, his sage recognises that all is one, but then goes further: ‘even this one does not exist!’

This nihilistic concept Kazantzakis took from Zen Buddhism, and it is no coincidence that the Ryoan-ji temple was Buddhist. For Buddhists, the rock garden was not designed for sensual pleasure, but for contemplation and recognition of transient reality. Zen adepts were prompted to realise, amongst other things, the world’s ephemerality, while savouring the simple poignancy of things: what the Buddhists call tath-at-a, or ‘suchness’. In this, the karesansui was a meditative device—another of Kazantzakis’ spiritual exercises: a reminder not to crave worldly things.

But while he was inspired by this vision of nothingness, Kazantzakis was not content with idle meditation or otherworldly apathy. One ‘gains courage from the horror’, as he put it in a letter to Emile Hourmouziós. This is why his book The Saviors of God concludes not with quietist monasticism, but with ‘action’. The point was ‘not to look passively while the spark leaps from generation to generation’, he wrote, ‘but to leap and to burn with it!’ This ‘spark’ was, of course, another metaphor for his élan vital.

In this way, Kazantzakis’ philosophy was foremost a disciplining credo, which stressed constant effort and a Buddhist refusal to covet what one’s efforts achieved. Kazantzakis was wary of comfort, pride and deference to convention, because they diminished ambition and exertion. ‘The greatest sin’, he wrote to his first wife, Galatéa, ‘is satisfaction’. For him, élan vital was a grand cosmological and biological principle, but also a justification for worldly innovation: he saw himself as part of an ongoing struggle to keep shaping and reshaping reality—including the reality of himself. Hence his celebration (and sometimes deification) of perseverance and conflict. ‘You’re seeking God?’ Kazantzakis wrote in his Symposium. ‘Here He is! He’s action, full of mistakes, gropings, perseverance and struggle. God is not the force that found eternal harmony, but the force that breaks every harmony, always seeking something higher.’

Violating their visions of godly perfection, his writings were attacked by the Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches, but Kazantzakis was not cowed. ‘If you are a man of learning, fight in the skull’, he wrote in The Saviors of God, ‘kill ideas and create new ones’. This applied to his own work and life too. Kazantzakis continually strived to transform his ideas and impressions into literature, and then to overcome these in the next poem, novel or play. It was, for him, a kind of war against inertia. Witness Kazantzakis’ battle cry in Journeyings, prefacing his travels to Europe and the Middle East: ‘Words! Words! There is no other salvation! I have nothing in my power but twenty-four little lead soldiers. I will mobilize. I will raise an army’. And these soldiers, in turn, were destroyed or discarded by others, and transformed once again. ‘Again the ascent begins’, as he put it in The Saviors of God.

In this way, the élan vital was a metaphysical version of Kazantzakis’ own daily literary and philosophical drive. ‘I’d like to rest a bit’, he wrote, three years before his death in 1957, ‘but how? I’m in a hurry. Some voice within me is in a hurry, merciless’. Right up to the end, this was Kazantzakis’ outlook: struggle, sacrifice and fleeting transformation.

A Private Sinai

Kazantzakis recognised this ideal as he contemplated the stones of Ryoan-ji: restless innovation. At first, this might look absurd: seeing primal vitality in dead stones. But for Kazantzakis, austere landscapes were precisely where the most animated, animating ideas were born. Austerity was an opportunity for élan vital to do its work.

This was partly because stones, in Kazantzakis’ mind, were also part of the world’s becoming. ‘A stone is saved’, he wrote in The Saviors of God, ‘if we lift it from the mire and build it into a house, or if we chisel the spirit upon it’. Kazantzakis did not believe that stones were literally redeemed, in any Christian sense. It was a poetic way of putting his contempt for waste; for raw materials left without transformation. To develop itself, mankind had to continually labour with the world; to undertake the ‘transubstantiation’ of matter into new forms. ‘Every man has his own circle composed of trees, animals, men, ideas’, he said, ‘and he is in duty bound to save this circle. If he does not save it, he cannot be saved’.

For this reason, the author believed that the most harsh places were artistically inspiring: they forced people to create and destroy in this way, in order to survive. Travelling in the Sinai in 1927, Kazantzakis swayed to and fro for hours on his camel, reflecting on the fate of the Hebrews, confronting ‘desolate, waterless, unfriendly mountains, that despise man and repel him’. As the Israelites endured this desert, they became tougher, more brutal. As they did, their god transformed. ‘He was no longer a mass of anonymous, homeless, invisible spirits spilled into the air,’ the author wrote in Journeyings, ‘he had become Jehovah, the hard, avenging, bloodthirsty God of one race only, the God of the Hebrews’. This God, in turn, pushed the Jews to fight on, and justified their moral and political laws. As an ideal, God was the spiritualisation of the Hebrew will to survive, which arose in harsh climates. Kazantzakis also discovered this transformation in his home island of Crete, and travelling in Spain. He argued that the ‘wild uninhabitable mountains’ of Castile blurred reality and dream—it was a cruel, epic landscape. ‘The brain seethes’, he wrote in his travel book Spain, ‘and thinks all things are easy for a willing energetic spirit’. Shaped by his own austere childhood, he believed that barrenness offered rejuvenation. The only other option was death and extinction.

Elsewhere, Kazantzakis made exactly the same point in reverse. His books are dotted with references to sweet, fertile landscapes robbing men of the urge to strive. On the Greek island of Naxos, where his family fled occupied Crete, Kazantzakis discovered a more abundant life. ‘Everywhere huge piles of melons, peaches, and figs’, he wrote in his autobiography Report to Greco, ‘surrounded by a calm sea’. Naxos was comfortable and calm, but for Kazantzakis it was an unsettling invitation to complacency.

Nikos Kazantzakis was obviously a man of extremes: at once idealistic and carnal, lyrical and gritty. Half a century after his death, his intensity still comes across in his prose, rightly described by his friend Pandelis Prevelakis as ‘impetuous, elliptical, and often excited’. The author’s uncompromising style was captured in his stark epitaph: ‘I hope for nothing. I fear nothing. I am free’. Not everyone will have Kazantzakis’ obsessive work ethic, or penchant for mingling the ordinary and the metaphysical. ‘Within me, even the most metaphysical problem takes on a warm physical body’, he wrote in Report to Greco, ‘which smells of sea, soil, and human sweat’.

Nonetheless, Kazantzakis’ response to the Japanese karesansui is a striking example of a more common existential and artistic ambition. It is a reminder to keep transforming oneself and the world, while hinting at the ultimate futility of this struggle.

Three summers ago, I saw this exemplified in my late neighbour, a keen gardener. For weeks on end, he raked the stones of his gorgeous Edwardian garden. I remember him clearly: weakened by a stroke, and often unbalanced—he needed his walking frame to stay upright. But he dragged his rake over the path, pebble by pebble. It seemed pointless: day-to-day necessities—my children running to the front door, the dog galumphing back and forth, cars reversing out the gate—soon left it a mess. Surely his energies would have been better put into recuperation and recovery; into the retreat of convalescence. But he kept at it, waging his quiet war against the wayward quartz. That week, the following week, and so on—until he could no longer stand unassisted, let alone pick up the rake.

To me, this is a poignant example of Kazantzakis’ philosophy. My neighbour’s stones would never have budded or flowered, but they goaded him to keep transforming his path, without any promise of completion; to suffer the discomforts of age and illness, while keeping on. This is élan vital: a longing to create and destroy; to make and remake, invent and discard, even when it is seemingly useless. The dead pebbles are an invitation: to be more fully alive, while we still can.