Voltaire: The Best of All Possible Estates

Life is bristling with thorns, and I know no other remedy than to cultivate one’s garden.

Voltaire, letter to Pierre-Joseph de Boisjermain, October 1769

Tend your vines, and crush the horror.

Voltaire, letter to Jean d’Alembert, February 1764

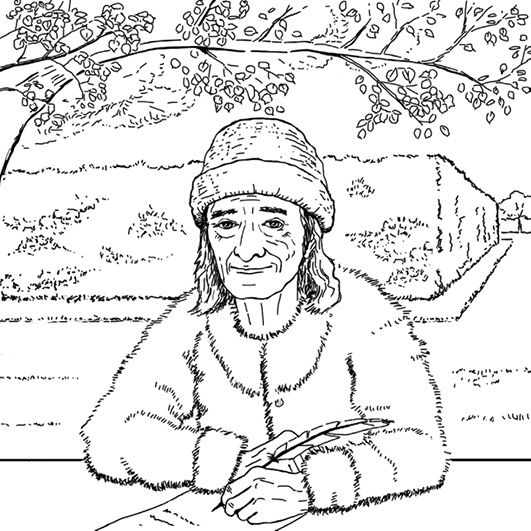

Wearing a thick fur coat, five silk caps and a woollen hat, Voltaire sits in his ‘cabinet’: not a luxurious study or a private chamber in his neoclassical mansion but a bench under an old linden tree. Afternoon sunshine has warmed the air, but the ‘monarch of French literature’, as James Boswell described him, is still shivering a little. In his mid-seventies, the great Enlightenment author—essayist, playwright, poet, satirist—is skin and bone (and nose, as the caricaturists remind him). As he sits and writes, he continually shifts on his seat—the prostate cancer that will kill him in seven years, in 1778, has already begun. But he keeps writing. Hidden by pergolas, seated just beyond the gravel and grass walks of his Ferney estate, he looks like a bourgeois retiree, writing instructions for his twenty-three gardeners or negotiating another lucrative loan. But what compels the wealthy septuagenarian to leave his sixteen-bedroom chateau is not household management or commerce. In his garden cabinet, Voltaire is living up to the motto he adopted in Prussia, as the kept philosopher of Frederick the Great: écrasez l’infâme, ‘crush the horror!’

The infâme was Voltaire’s nickname for what, in any era, destroys liberty and retards thinking. In his time, it was an alliance of fanatical state religion and French absolutism, which offended the author’s moral principles and caused him much public and private grief. For most of the eighteenth century, France was officially a Roman Catholic country. Church rituals, dogma and superstition ruled with little judicial redress, and the law itself was prejudiced in letter and application. Over his long life, Voltaire grew increasingly infuriated by oppression of innocent French citizens. For example, his friend and lover Adrienne Lecouvreur was denied a Christian burial. Her crime: working as an actress. While monarchs and aristocrats guiltlessly took parts in Voltaire’s plays, talented women like Lecouvreur were reviled as little more than prostitutes by priests, the aristocracy and French citizens alike. Aged just thirty-seven, and despite Voltaire’s frantic lobbying, Lecouvreur was dumped in a pauper’s grave in a wasteland on the Paris outskirts. Her English peer, actress Anne Oldfield, was buried only months later, in October 1730, in Westminster Abbey. For Voltaire, this pointless tragedy was the work of l’infâme. The same church and state alliance stopped official publication of Voltaire’s epic poem in praise of former Protestant King Henry IV, the Henriade. L’infâme also threatened Voltaire with imprisonment in the Bastille, without trial or judgement by his peers, for publishing the Henriade secretly. He had it printed in the more progressive, Protestant Netherlands, then smuggled into Paris in a wagon carrying furniture and on pack horses. For Voltaire, eighteenth-century France combined the worst of religious superstition—communion, petitionary prayer, holy wars, and beliefs like original sin—with foolish kings, malicious clergy and a corrupt parlement.

To fight the horror, Voltaire—baptised François-Marie Arouet—became a dogged reformer, philanthropist and provocateur. His aim was simple enough: ‘Less superstition, less fanaticism; and less fanaticism, less misery’. While he did believe in God as the supreme creator, he lambasted the Church, which he saw as a kind of grand debauch. He poked fun at the monarchy, advocated for persecuted Protestants and invested heavily in local businesses and infrastructure. With ardour that still invites readers to laugh alongside him, Voltaire never missed an opportunity for a dig at the priests. In 1764, American doctor John Morgan visited him at Ferney and was surprised at his venerable host’s fury against the French Church. ‘Hate hypocrisy, the masses’, he fumed, ‘and above all hate the priests’. James Boswell described Voltaire getting so steamed up at the clergy, ‘like an orator of ancient Rome’, that he almost fainted. Even his plays—aside from those sucking up to the French court—were jabs at religious bigotry. He believed that even the cruellest zealots would weep if they saw their own crimes on stage. ‘Tears’, he aphorised in his philosophical dictionary, ‘are the mute language of sorrow’. But Voltaire had more up his sleeve than melodrama. Somewhere between columnist and stand-up comedian, he also skewered his peers with satire and quips. ‘No one has ever been so witty as you are in trying to turn us into brutes’, he gibed at Jean-Jacques Rousseau, ‘to read your book makes one long to go on all fours’.

For all his public debates, Voltaire was not committed to academic niceties (‘All the philosophers were unintelligible’, he quipped). He wanted to drive change: in minds, and increasingly in French laws, technology and behaviour. ‘There is a point beyond which research satisfies only curiosity’, he wrote in his Philosophical Letters, finished after his return from relatively free-thinking and tolerant England, in 1729: ‘those ingenious and useless truths resemble stars that are too far from us to give us any light’. In this, Voltaire was not a philosopher in the more modern sense—a systematic theorist, disinterestedly pursuing truth for its own sake. He was closer to the ancient Greek philosophers like Socrates and the Stoics: interested in science and the nature of reality, but more concerned with using reason to improve themselves and society—what the eighteenth-century French called a philosophe. ‘Man is born for action’, he wrote against the Christian philosopher and mathematician Blaise Pascal, ‘as sparks fly upwards … Not to be active and not to exist are the same thing for mankind’. And Voltaire had more spark than most.

‘Let Us Cultivate Our Garden’

For Voltaire, the gardens of Ferney were an emblem of his ‘action’; of altruistic local reform, opposed to a stubborn conservatism. He made this statement boldly in his story Candide, published in 1759, just after he settled at Ferney. The butt of his book-long joke is a kind of metaphysical optimism, voiced by Dr Pangloss, who is a stand-in for philosopher Gottfried Leibniz and others, including Voltaire’s younger contemporary Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Pangloss believes that this world is the best of all possible worlds, in which ‘everything is best’, cosmically speaking. Rape, torture, poverty, starvation might seem like the work of a cruel or incompetent deity, but they are just parts of a magnificent whole (we might call them ‘metaphysical collateral damage’). When combined with widespread inequality and injustice, this philosophy sent a profoundly conservative message: ignore the world’s brutality, because all is for the best. Voltaire showed his hero, Candide, naively accepting these platitudes, then being forced to confront their absurdity. After witnessing a series of horrors, and suffering many himself, Candide rejects ‘metaphysico-theologico-cosmolo-nigological’ shenanigans in favour of what looks like a retreat into a quiet life. His final retort to Pangloss is now famous: ‘Let us cultivate our garden’.

At first, this looks like a limp riposte to suffering—a disengagement from the world, out of step with his well-deserved reputation as a literary duellist. And it’s true that Voltaire did write much of Candide at Ferney, well removed from the king’s court and parlement. Having already seen the inside of a Bastille cell, and endured exile from Paris, Voltaire was determined to evade the French authorities. Pays de Gey, where Ferney was situated, was far from the seats of power in Paris and Versailles, and close to the border if he needed to escape to Switzerland or the Prussian protectorate of Neuchâtel. Having spent much of his youth and middle age moving from one patron to another, and at the mercy of local lords and clergy, Voltaire learnt that distance could safeguard his literary freedom. King Frederick of Prussia once referred to the philosophe as an orange, to be squeezed for amusement, then thrown away. Voltaire resolved to ‘place the orange peel in safe keeping’. When he purchased Les Délices (‘The Delights’) he was upfront about these interests. ‘I speak what I think’, he wrote from Les Délices, ‘and do as I will’. At Ferney, just inside the French border, Voltaire was having his brioche and eating it: the security of Switzerland, but on his native soil.

Voltaire was also using his estates to avoid the distractions of fame. By the time he purchased Ferney in his sixties, Voltaire was less a celebrity and more a literary Olympian. He arrived at Ferney and Tourney in a luxury coach, dressed in crimson velvet and ermine, and was greeted with bouquets, baskets of oranges and a cannon salute. Over the year he received visitors like a king at court, particularly English and Scots travellers on their Grand Tour (one hundred and fifty Englishmen in a decade, his biographer Roger Pearson reports). ‘For fourteen years now’, he wrote in 1768, ‘I have been the innkeeper of Europe’. Because of this popularity, and his duties as a landlord and philanthropist, Voltaire was regularly interrupted. His Ferney walks and arbours provided pleasant asylum from the many guests at his own chateau. At his bench, hidden by ‘evergreen hedges’, Voltaire reclaimed the solitude and silence he had lost to fame.

But for Voltaire, the garden did not symbolise monkish quietism—quite the contrary. It certainly shielded him from attacks and distractions, but it was also a bold metaphor for compassion, responsibility and pragmatism—a call to improve his immediate surroundings. Voltaire argued that the world was marred by misery and cruelty, and no benevolent, all-powerful god would ever arrive to tidy up the mess. There was no great plan—no providence—and certainly no divine mandate for kings and clergy. But this, for Voltaire, was not cause for cynicism or fatalism. Nature gave humankind reason and hope, and it was up to us to improve our lot. Instead of toying with grand philosophical systems, or becoming mad with power, we ought to start within our own sphere of influence: our marriages, children, towns and humble backyards. Hence Voltaire’s commitment to his estate. The wheat of Ferney would not miraculously grow itself; to provide the bread at the baron’s table, the fields had to be planted and reaped, year after year. Ferney required practical expertise, continual labour, and devotion. And likewise for civil institutions: the estate stood for France as a whole, which deserved to be governed wisely, benevolently, tolerantly. This is the point of Voltaire’s conclusion: Candide’s garden required careful, attentive custodianship—one that nurtured the community as well as the soil.

This wasn’t just a literary flourish in Candide. Horticulture was an ongoing theme in Voltaire’s correspondence, particularly when encouraging reform. Writing to the mathematician and Encyclopedist Jean d’Alembert, for example, Voltaire argued that the time was right to ‘topple the colossus’ of religions and tyranny. ‘Tend your vines’, Voltaire told d’Alembert in 1764, ‘and crush the horror’. This metaphor was used regularly in Voltaire’s letters to the Encyclopedists, along with images of fruits, flowers and ‘sowing the good grain’. For Voltaire, gardening and enlightened reform were part of the same project: the use of one’s natural intelligence to promote liberty and opportunity. To ‘cultivate one’s garden’ was to make this world, right here and now, a little better.

Importantly, Voltaire’s chateau gardens were practical examples of this, Candide’s message of progressive custodianship. They did not merely symbolise the Enlightenment: they were it. In 1735, before he purchased Ferney, the author set up house in Cirey, the rural mansion of his then-lover, mathematician and scientist Émilie du Châtelet. The couple planned the grounds together and bickered happily about it. ‘She has limes planted where I had settled on elms’, grumbled Voltaire to the Comtesse de la Neuville in 1734: ‘she has changed what I made into a vegetable plot into a flower garden’. It was a form of independence, but also of altruistic improvement—and it stuck with Voltaire, well after Émilie’s tragic early death. In 1755, Voltaire and his new companion (and niece) Madame Denis moved into Les Délices in Geneva. Immediately, they saw to the gardens. They ordered flowers and herbs, grew asparagus and artichokes in the greenhouse, and planted apple, peach and pear trees. For the landlord, this was more than an amusement: it was a way to take responsibility for himself and others. He pictured himself not simply as a free author or an entitled king but as a generous elder. ‘Here I am’, wrote Voltaire in the spring of 1755, with a touch of anti-ecclesiastical irony, ‘finally leading the life of a patriarch’. Voltaire even offered Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose ideas he lampooned, Les Délices’ amenities: freedom, soft grass and ‘the milk of cows’ (Rousseau, predictably, declined).

At Ferney and Tourney (a sister estate, 3 miles away), Voltaire was more industrious still. In keeping with his commitment, he drained marshes, fertilised and sowed fields, and planted vines. Much of his estate’s produce ended up on the banquet table for his many guests. ‘Show me in history or fable, a famous poet of seventy who has acted in his own plays, and has closed the scene with a supper and ball for a hundred people’, wrote visitor Edward Gibbon in 1763. ‘I think the last is the more extraordinary of the two.’ (The author of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire probably knew a thing or two about feasts.) Voltaire even kept a plot close to the Ferney chateau, which he worked personally— ‘M. de Voltaire’s field’, it was called. Formal gardens were also carefully arranged, alongside parkland planted with oak, linden and poplar—including the landlord’s pergola cabinet, with silkworms nearby (perhaps the source of his many caps).

Alongside his campaigns for judicial reform and human rights, Ferney and Tourney were a vital part of Voltaire’s struggle against l’infâme—the campaign to leave his France better than he found it. If Kings Louis XV and Frederick, busy with imperial warmongering and profiteering, would not improve their territories, Voltaire would at least see to his.

The Voice of Nature

Gardens, in this way, were symbols and examples of Voltaire’s ethical project. They also inspired him to keep working at it. To do this, they presented him with a vision of nature’s intricacy and grandeur. As a deist, Voltaire was convinced by the argument from design: a universe this elegant was not the result of chance. ‘The world is assuredly an admirable machine’, he wrote in his Philosophical Dictionary, ‘therefore there is in the world an admirable intelligence’. So in Ferney’s sunrises and its fields, Voltaire saw a deeper pattern: not a revelation of Church doctrine, or the divine right of kings, but of godly beauty and intelligence. And this recognition, in turn, held a message of goodwill and responsibility: toward a sacred but imperfect and unpredictable universe. It was not the best of all possible worlds, in which ‘all was well’. But it was well designed, and amenable to tinkering. With brains, elbow grease and goodwill, it could become better. In his 1763 ‘Treatise on Tolerance’, Voltaire summed up this philosophy, putting his own credo into the mouth of nature itself:

I have given you strength to cultivate the earth, and a little glimmer of reason to guide you; I have implanted it in your hearts an element of compassion to enable you to assist one another in supporting life.

By meditating upon nature in this way, Voltaire was moved to continue his reforms; to keep labouring, despite the fact that he no longer had the best of all possible eyes, teeth and digestion. The earth was not telling him to pray for God’s grace, or to burn heretics for their unorthodox metaphysics (‘Almost everything that goes beyond worship of the Supreme Being and the heart’s submission to its eternal order’, he wrote, ‘is superstition’). The fields and lindens of Ferney had a more progressive message: François-Marie, tend to your vines already.

So for Voltaire, security and peace were part of a more profound commitment to responsible, rational progress, and the goods of nature that enriched and encouraged this. If Ferney became the philosophe’s best possible world, this was not because of a god’s love or a king’s favour. It was because M. Voltaire, like his Candide, had indeed cultivated his gardens—and they him.