Friedrich Nietzsche: The Thought-Tree

Whatever in nature … is of my own kind, speaks to me, spurs me on, and comforts me; the rest I do not hear or forget right away. We are always only in our own company.

Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science

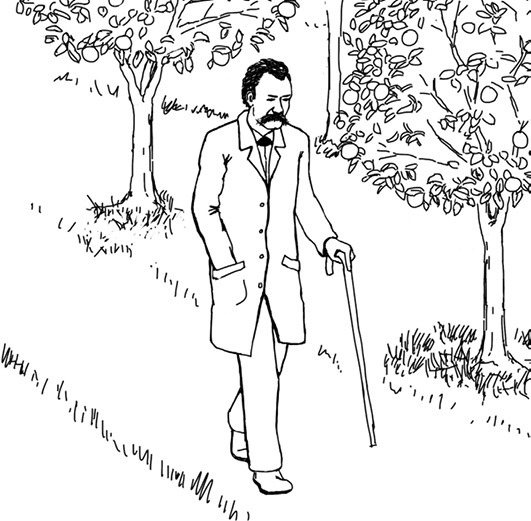

Friedrich Nietzsche loitered under a lemon tree, muttering to himself. To the locals of Sorrento, the orchard was nothing special: a source of fruit and Limoncello, their famous bittersweet liqueur. But for the young philosopher—then thirty-three, on leave from his Basel professorship—the citrus grove was much more. Shading his red, squinting eyes from Italy’s autumn sun, Nietzsche walked and collected his ‘wicked thoughts’. It was a vital part of his daily philosophical routine.

For the delicate Prussian-born author, the morning began with warm milk and a cup of tea. Then there was dictation of letters or ideas to Albert Brenner, another young German staying at the Villa Rubinacci, which was rented by their patron Malwida von Meysenbug. Then Nietzsche took himself off for a long walk—often for hours. His ideas came as he strolled, or wandered under the foliage. And they came copiously. In her memoirs, Meysenbug described Nietzsche’s furious work as he tried to finish his new book before madness and death stole him away (he lived another ten years before the first, and twenty before the second). Decades after that autumn, Meysenbug took the trouble to immortalise one detail: every time Nietzsche stood under this one particular tree, a thought ‘fell’ to him. His biographer Curtis Cate says this was called Nietzsche’s Gedankenbaum, or ‘thought-tree’.

Throughout his career, Nietzsche did much of his thinking in gardens, parks and woods. ‘I need a blue sky above me’, he told his friend Paul Deussen, ‘if I am able to collect my thoughts’. For this reason, Nietzsche was very particular about his homes: they needed just the right combination of landscape and climate. In Nice, in early 1887, he saw forty houses before finally choosing. And once settled, he rarely stayed for long. His yearly itinerary was a continual, vain chase for the perfect weather. When he was pensioned off by Switzerland’s Basel University in May 1879, he fled to Davos in the mountains. But the weather was not promising, so he moved to St Moritz, in the Engadine mountains. ‘It is as if I was in the Promised Land’, he wrote buoyantly to his sister Elizabeth. But his new Eden was soon mired in cloud and snow. So he headed to Venice, Marienbad in Bohemia, Naumburg in Germany, Basel, then several more Italian towns. ‘Where is the land with a lot of shade’, he asked his friend, the composer Henrich Köselitz, ‘an eternally blue sky, and equally strong sea-wind from morning till evening, without thunderstorm?’ Nietzsche died having never discovered his utopia.

One reason for Nietzsche’s fussiness about where he lived was illness. In 1876, before his departure for Italy, Nietzsche was diagnosed with blindness and prescribed deadly-nightshade eye drops. In agony, he rationed his reading to an hour or so a day—a pittance for a scholar like Nietzsche. This is partly why he craved the lemon tree’s shade in Sorrento: to stave off eyestrain and crippling headaches from the Italian sun.

Another reason was that Nietzsche was a loner of sorts, easily bruised by praise and condemnation. When Human, All Too Human was published in 1879, Nietzsche was struck with nausea and vomiting—a psychosomatic ailment, caused by the knowledge that his book was being read. His relations with women also swung between abandon and depression, as he gave himself over to the fantasy of love or marriage, and was then crushed by reality. After his disastrous, abortive ménages with Paul Rée and Lou Salomé, Nietzsche was so ill he was ready to shoot himself. Of course the philosopher could be witty, amiable and charismatic at times. But Nietzsche was not made for ongoing intimacy. For this reason, he craved solitude. ‘That I would be alone by the time I was about forty—about this’, he wrote to Köselitz in April 1884, after the Salomé affair, ‘I have never had any illusions’. For Nietzsche’s hero, the eponymous Zarathustra, the alpine forests were an escape from ‘parasites, bogs, vapours’—metaphors for what he saw in the towns. Herr Professor Nietzsche was little different. ‘We like to be out in nature so much’, he wrote in Human, All Too Human, ‘because it has no opinion of us’. Italy’s lemon grove was, for the philosopher, comfortingly inhuman—a little Lebensraum, ‘living space’, or what he called, in Beyond Good and Evil, ‘the “good” solitude’.

Walking in Ourselves

In the landscape, the philosopher was also seeking himself: a ‘higher’ Nietzsche, who was best discovered in groves or on mountainsides, rather than in churches or seminar rooms. In The Gay Science he said that his ideal building needed cloisters, so he could be closer to rocks, flowers and trees, and thereby closer to himself. ‘We wish to see ourselves translated into stone and plants,’ wrote Nietzsche, ‘we want to take walks in ourselves, when we stroll around these buildings and gardens’. This was partly a criticism of religious architecture, with its Christian symbolism—oppressive for the atheist. But it was also because nature reminded him of his own existential ambitions.

This project hinged on Nietzsche’s radical philosophy of nature, and his criticisms of nineteenth-century thought. The intellectual mood at the time was broadly idealistic. While science was growing rapidly, many scientists—including Darwin—were still deists who believed that the mechanical universe had a supernatural inventor. In philosophy, many of the ruling theories were Christian, or inspired by traditions sympathetic to Christianity, like Platonism. Another popular movement was Romanticism—a broad artistic church, which often saw emotion, spontaneity and organism as fundamental. Common to both traditions was the conviction that nature, broadly understood, had some special value or purpose, intelligible to the theologian, prophet or artist.

Nietzsche—the pious son of a pastor, and a devoted follower of Wagner and other Romantic composers— was originally moved by both traditions. But he eventually saw his era as self-deceiving, mistakenly giving nature human characteristics, like rationality or feeling, and revelling in sentimentality instead of brutal honesty. Seeing the world as ‘lack of order, arrangement, form, beauty, wisdom, and whatever other names there are for our aesthetic anthropomorphisms’, Nietzsche had no truck with nature as an organism or machine, artwork or divine law—these were all deceptive metaphors. Most involved metaphysics: the idea of an intelligible world, which belied or justified the perceivable one. ‘All that has produced metaphysical assumptions, and made them valuable, horrible, pleasurable to men thus far’, he wrote in Human, All Too Human, which he was composing as he strolled in Sorrento, ‘is passion, error, and self-deception’. A genuine thinker, for Nietzsche, was able to confront the universe as it was, without inventing some deity, spirit or grand destiny as a cosmological or existential guarantor.

But for Nietzsche, this philosophical maturity was rare. Because of this, enlightened Europe was haunted by nihilism—what he called, in The Will to Power, the ‘uncanniest of all guests’. The growth of reason and science, Nietzsche argued, often went hand in hand with idealism and sentimentality. Think of Darwin’s deist god, comforting the naturalist as he developed his ‘godless’ hypothesis: evolution by natural selection. But all over the West, progressively more of mankind and nature were deprived of supernatural explanation and validation. New disciplines arose, which applied empirical, logical analysis to more domains: psychology, anthropology, sociology, alongside the physical sciences (Nietzsche called himself a ‘psychologist’). Traditional ideas—god, soul, divine grace, predestination—lost their taken-for-granted truth. For many, the result was nihilism: having invented and believed in eternal and universal ideals, modern man was disoriented and disillusioned without them. Without some religious or cosmic source of value, there was no value—or so it suddenly seemed. This is why, in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche boldly proclaimed the ‘death of God’: not because there ever was a god, or because the philosopher was a deicide, but because the West was slowly destroying its own illusory footholds—and was struck by profound vertigo as it did so. This was the point of the madman’s marketplace harangue in The Gay Science:

Is there still any up or down, are we not straying as through an infinite nothing, do we not feel the breath of empty space, has it not become colder, is not night continually closing in on us … do we hear nothing as yet of the noise of the grave diggers who are burying God? Do we smell nothing as yet of the divine decomposition?

Contrary to his reputation, Nietzsche’s response to this divine funeral was not to champion nihilism—far from it. Instead, he believed the best minds had to be more honest about what they were doing all along: imposing themselves upon the world, and one another. He railed against the myth of ‘pure’ motives in art and scholarship. Importantly, Nietzsche had no moral problem with this; he simply wanted more candour and judiciousness. This is Nietzsche’s famous doctrine of the ‘will to power’: mankind as just another selfish organism, at its best with physical strength, intellectual clarity and courage, emotional abundance. In this vision, we cannot look to the universe for ultimate value or ideas, or to society, but only to ourselves. ‘What? A great man?’ he asked in Beyond Good and Evil: ‘I always see only an actor of his own ideal’. Greatness is a performance, in which we are the actors, audience and judges.

Free Spirits

For this reason, Nietzsche’s cosmology stressed process above all: creation and destruction, growth and decay, birth and death. For Nietzsche, nature provided no ‘should’ or ‘ought’. It was amoral. Its virtue was its fickleness and fertility. Animals and plants lived and died, but nature as a whole kept experimenting with new species and environments. It was a lesson in the brutality of evolution. But it also taught a certain profligacy: over millions of years, nature had been guiltlessly throwing away life for innovation’s sake. There was no progress, no purpose, just a parade of novelty, which sometimes delivered beauty, strength and health—and sometimes disfigurement, impotence and disease.

Nietzsche’s existential vision echoed this process. What he wanted of his supermen—Zarathustra, Dionysus, ‘great man’, ‘free spirits’—was what he asked of himself: a willingness to guiltlessly destroy old ideas and values, regardless of the pain involved. To be honest, in other words, about human responsibility for human development, rather than deferring to a fictional ideal. And behind this was a strong will: able to bear pain, loneliness, mockery, grief, without giving up in favour of supernatural consolation. ‘Philosophising with a hammer’, he called it in Twilight of the Idols. Nietzsche’s mallet-wielding Übermensch (‘superman’) was not just a destroyer, however. He believed in discipline, restraint, delicacy and subtlety. Nature taught Nietzsche how much of his psyche was organic and instinctual, but he mastered these with what, in The Gay Science, he called ‘style’. ‘Weak characters without power over themselves’, he wrote, ‘hate the constraint of style’. Strong characters like Nietzsche willed themselves into existence in this way—even when they were lonely and ill, as was the philosopher.

In this new outlook, nature supplied the materials and tools, but not the blueprint: science, metaphysics or theology gave no certainties. Hence Nietzsche’s contempt for anti-Semitism and nationalism, with their false foundations of biology or state, and his disgust with his own proto-Nazi brother-in-law, fooled by absurd notions of German superiority. They were not really supermen: they were weak fools, he believed, unwilling or unable to live without illusory certainty. Mankind, asserted Nietzsche, had to be stronger: to experiment with itself, without guarantees or promises—just like plants and animals. Nietzsche’s supermen had to live dangerously and build houses next to Vesuvius, as he quipped in The Gay Science. They had to be like a tree on a cliff, he wrote in Zarathustra: ‘calmly and attentively it leans out over the sea’ (note the botanical metaphor for solitude and superiority). More literally, Nietzsche’s great men had to forgo universities and salons, and get out into the earth’s power and profligacy. Sitting thinking indoors was for ‘nihilists’ (he accused the French novelist Gustave Flaubert of this).

For Nietzsche, Sorrento’s citrus grove offered no comforting vision of a lawful, benign cosmos—no relaxing break. It was a challenge to experiment: with his ideas, values, career and relationships. The ‘thought-tree’ asked him to turf the reassuring certainties of family, class and his traditional education; to be as violent, unpredictable and innovative as nature. In this way, Nietzsche’s gardens helped him to press on with his radical innovations in theory, literature and the German language.

The result was decisive. Not long after Sorrento, Nietzsche’s life was transformed. Significantly, he broke with his idol, the composer Richard Wagner, partly because of Wagner’s overbearing attitude—curt letters ordering the young professor to send him pants did not sit well with Nietzsche’s headaches and nausea. But it was also a philosophical separation. With his newfound naturalism, Nietzsche found Wagner too mystical, otherworldly, sentimental—too ‘Christian’, in a word. He also saw Wagner’s increasing ‘guru’ status as a barrier to the composer’s greatness. Too much fawning was robbing Wagner of proper criticism and opposition; the strife that drives great souls was replaced with sycophancy. In Wagner he saw decadent retreat. For similar reasons, Nietzsche also took issue with Arthur Schopenhauer, whose works he had lauded as a student. While respecting the Danish philosopher’s steely pessimism, ‘process’ outlook and lively prose, Nietzsche accused him of Wagner’s crime: a quietist, defeated withdrawal from the world. This was a life-denying philosophy, whereas the young philosopher wanted to say ‘yes’: to instinct, flesh and their natural foundations. The Nietzsche of Sorrento was increasingly an evolutionary advocate.

Nietzsche was also, after the Villa Rubinacci, increasingly alone. Coinciding with his increased naturalism was a greater urge to escape Basel’s intellectual climate in favour of the seaside, alpine walks or occasional ‘cures’ abroad. He avoided big cities, parties and, after he received his pension from Basel University, academic employment. Gone was the urban classics scholar and Schopenhaurian Wagner disciple. In his place was a lone positivist philosopher, increasingly preferring the company of gardens and parks to books, cafes and professional peers. He would not have a conventional marriage, or—he soon realised—any marriage at all. He would become increasingly hostile to his mother’s and sister’s conservatism (‘When I look for my profoundest opposite’, he wrote in Ecce Homo, his autobiography, ‘I always find my mother and my sister’). All this was bound up with his naturalistic bent and push to independence. His eventual madness robbed him of this freedom; as he died in his sister’s care, unaware of his own contribution to modern arts and letters, and his sister’s Nazi perversion of it. But while he was lucid, Nietzsche achieved an impressive distance from conservative ideas, and distracting familial entanglements. The orchards and woods of Sorrento were a step in Nietzsche’s path to becoming a radical philosopher. They encouraged the genius he stubbornly willed himself to become, even as his eyes and mind gave way.

In this way, the citrus garden helped Nietzsche to be the ‘posthumous man’ he proclaimed himself to be in Ecce Homo. In the decades after his death in 1900, Nietzsche’s radical ideas had a profound influence on modern thought. Not as a single system, and much less the exalted spiritual authority co-opted by the Nazis, but as a legacy of intellectual courage, originality and clarity. ‘What we are left with is not a doctrine that might be preached’, as Nietzsche’s biographer RJ Hollingdale put it, ‘but a human individual, an artist in language of great skill and power, and a philosopher of compelling insight and strictness of principle’. Some of the greats of twentieth-century philosophy—Henri Bergson, Martin Heidegger, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, to name a handful—owed Nietzsche an intellectual debt. Psychology, including the seminal works of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, has deep Nietzschean veins: the pathological conflict between individual and society; the unconscious and instinctual basis of art and ideas; the opacity of consciousness to itself. Nietzsche also informed artists and authors, from the epic modern novels of Thomas Mann and Robert Musil, to Mark Rothko’s mythic colours and Giorgio de Chirico’s still, surreal landscapes. The man whom biographer Rüdinger Safranski called a ‘laboratory of thinking’ still inspires the experiment of modern life and thought.

Become What You Are

A Nietzschean garden is a straightforward existential challenge. It is a lesson in Nietzsche’s dictum, borrowed from the Greek poet Pindar: ‘Become what you are’. Most obviously, nature offers an encounter with the planet’s blind forces. The Nietzschean realisation that the cosmos is meaningless and pointless can be profoundly liberating. It suddenly makes common sense and traditional values look petty or small, which can be a vital first step toward the cultivation of independence. More importantly, it also suggests that second nature, our nature or physis, is unfinished; that humanity is not fixed by cosmological law or divine decree. This is Nietzsche’s point: we are a work in progress, like Sorrento’s lemons and firs—only we can craft ourselves more deliberately.

As a corrective, the garden also reveals how difficult this lived Bildungsroman is; how easily our freedom is compromised. However modern we are, we’re still at the mercy of instinct, habit and reflex—as was Nietzsche with his strains of misogyny, for example. The garden mirrors this conflict: even the most pedantically clipped yard—mown, pruned and weeded—is continually subject to forces that override pattern and order. Yet Nietzsche believed our own nature can also be tamed. This is why, in Human, All Too Human, Nietzsche wrote of ‘sobriety of feeling’: we have to be somewhat ruthless with ourselves, to overcome addictions, delusions and false idols. The point is not abstract knowledge, but what the philosopher called ‘style’: a more striking, graceful and refined life, which boldly combines biological inevitability with psychological autonomy. And this is precisely the balance he saw in Sorrento, his childhood home in Röcken, and the roses and geraniums of Nice (‘Not at all Nordic!’ he noted mischievously to his sister and her husband). In his example and in the gardens that inspired it, Nietzsche challenges us to cultivate ourselves with courage and artistry, rather than giving in to distraction, or what’s ‘done’. ‘How we hasten to give our heart to the state, to money-making, to sociability or science’, wrote Nietzsche in ‘Schopenhauer as Educator’, ‘merely so as no longer to possess it ourselves’.

The Wanderer

A decade after Sorrento’s thought-tree, aged forty-four, Nietzsche went mad—perhaps from syphilis, contracted in one of his rare sexual encounters. But the landscape kept its existential value for him. While writing Ecce Homo, Nietzsche went into raptures over Turin’s autumn. In October 1888 the philosopher wrote somewhat manically of the ‘glorious foliage in glowing yellow’, and ‘the sky and the big river delicately blue’. Intellectual clarity was replaced by a kind of mythic luminosity—more prophetic than philosophical. ‘A Claude Lorraine’, he wrote of the city, referring to the French neoclassical landscape painter, ‘such as I never dreamed’. Within months, he was signing his name ‘Dionysus’, and writing of his plans to shoot the Kaiser. In his poor, cracked psyche, Friedrich Nietzsche had finally become his superman, and all of Turin’s gardens radiated with this tragedy.

Saddening as this is, it’s important to see the lucidity of his lifelong devotion to gardens, and the outdoors. Throughout his career, Nietzsche’s unusual sensitivity to nature informed his ideas, symbolising a certain freshness and brightness of thought, free from metaphysical gloom and existential sloth. Nietzsche the mad, conspiratorial Dionysus was also Nietzsche the ‘Wanderer’ from Human, All Too Human, thankful for his thought-tree:

He strolls quietly in the equilibrium of his forenoon soul, under trees from whose tops and leafy corners only good and bright things are thrown down to him, the gifts of all those free spirits who are at home in mountain, wood, and solitude, and who are, like him, in their sometimes merry, sometimes contemplative way, wanderers and philosophers.