Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Botanical Confessions

I am convinced that at any age the study of nature … bestows upon the mind a salutary nourishment by filling it with a subject most worthy of its contemplation.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, letter to Madame Étienne Delessert, 1771

Philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s greatest talent was not logic, morality or metaphysics. It was self-portraiture. Rousseau’s literary works left a striking sketch of the author: a new kind of eighteenth-century Frenchman, brave, sincere and just. This was idealised, of course. ‘My innate goodwill towards my fellow men; my burning love for the great, the true, the beautiful’, he boasted in his Confessions, ‘my inability to hate, to hurt, or even to want to’. In the sentimental spirit of the age, and with more than a little conceit, Rousseau spared no superlatives when describing his own virtues.

Rousseau’s literary persona inspired the rich patrons, like the Duke and Duchess Montmorency-Luxembourg, who housed, fed, clothed and defended him (the duchess hoped to one day ‘merit a tiny part’ of Rousseau’s friendship). It also inspired the leaders of the French Revolution, who hailed Rousseau as a modern martyr for truth. The Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle once quipped that the second edition of Rousseau’s The Social Contract was bound in the hides of those who mocked the first. In fact, the bourgeois revolutionaries often ignored The Social Contract, but Rousseau’s autobiographical and fictional works—like Confessions and Julie: Or, a New Heloise—kept his portrait alive and loved. If France under the Ancien Régime was corrupt, false and selfish, this Rousseau was upright, honest and altruistic. ‘Divine man’, said Revolutionary leader Maximilien Robespierre, ‘I have contemplated your august traits. I have understood all the sorrows of a noble life devoted to the cultivation of truth’.

But all of Rousseau’s virtues, genuine and counterfeit, were prefaced by his gifts with the pen. Rousseau the author invented Rousseau the saint—and did it with boldness, lyricism and canny intelligence. When he won the Dijon Academy’s prize for his essay on arts and sciences in 1750, the author’s arguments—lambasting the degeneracy and weakness of intellectual life—were by no means original. Roman satirists had made the same arguments over a millennium earlier. What made the essay so striking was Rousseau’s prose—what his biographer JH Huizinga described as ‘the hyperbole, the defiant, not to say offensive, tone’. It gave him entry into the highest Parisian salons, his ferocity and righteousness lauded by the very aristocrats he was railing against. Rousseau had a talent, he wrote quite rightly in his Confessions, ‘for telling useful but unwelcome truths with some vigour and courage’.

Raptures and Ecstasies

But for long spells, writing was not this best-selling author’s passion. The autumn of 1765 finds Rousseau not at his study, pen in hand, but on his belly in the woods of Saint-Pierre, an island on Switzerland’s Lake Bienne. Here, Rousseau was in exile.

His Emile: or on Education was published three years before, and greeted with condemnation and censure by Roman Catholic and Protestant authorities alike. His offence was to put heretical ideas—disbelief in original sin and revelation, amongst others—into the mouth of a Catholic vicar, and to sign the book with his own name (France was more tolerant of anonymous radicalism). His books were burned; his life was threatened, and warrants were made out for his arrest. He fled France to Motiers in Switzerland, then rushed to Saint-Pierre when his house was stoned in the middle of the night.

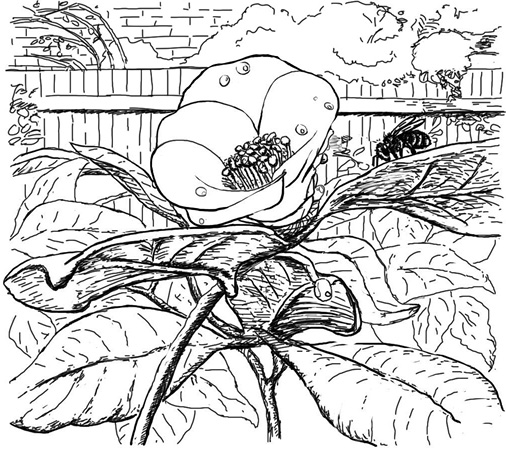

Ensconced in the island’s woods, Rousseau looked the part of the religious iconoclast: dressed eccentrically in an Armenian robe bordered with Siberian fox, and a grey squirrel cap (more Davy Crockett than Martin Luther). To his left, on a lichen-covered rock, a copy of Carolus Linnaeus’ Systema Naturae, the work of the great Swiss zoologist. In his right hand, a magnifying glass. Rousseau’s prominent nose was only inches away from the purple flower of a self-heal, or Prunella vulgaris. The self-heal’s pollen-covered stamens, he discovered, were long and forked—a trick of fertilisation that gave him ‘joy’, he said.

In this way, on the tiny island, Rousseau spent hours after breakfast, drawing and making notes, often taking home specimens to dissect or dry. He collected meticulous observations on the structure and sexual reproduction of plants, and was compiling his Flora Peninsularis: a study of the island’s plant life. It was the most fun the infamous philosopher could have alone (Confessions records, in wince-worthy detail, his other solitary pursuits). ‘Nothing could be more extraordinary’, he reminisced in his Reveries of the Solitary Walker, written back in Paris, two years before his death in 1778, ‘than the raptures and ecstasies I felt at every discovery’.

Guttersnipe of Genius

Saint-Pierre’s plants were perfect companions for Rousseau, whose friendships were famously tempestuous. Philosophers like Diderot respected him but eventually broke with him over his rudeness, vilification of mutual friends, and martyr fantasies. Madame d’Epinay, a patron he accused of plotting against him, later described Rousseau as a ‘moral dwarf on stilts’. The Scottish philosopher David Hume, with whom Rousseau stayed in England during his exile from France, tried to secure the French author a pension from the king. For his labours, Hume was rewarded with charges of cruelty and conspiracy. ‘You have brought me to England’, Rousseau wrote to the baffled philosopher, ‘allegedly to procure my asylum but in fact to dishonor me’. By this stage, Rousseau was showing symptoms of the madness that plagued him toward the end of his life. But even without insanity he was often tetchy and ungracious.

Rousseau also felt like an outsider in Parisian salons, and clumsy alongside the witty philosophes like Voltaire. He was too capricious and undisciplined to research and write rigorously, or cultivate his courtly demeanour. ‘I abandon myself’, he wrote in a letter, ‘to the impression of the moment’. Unable to polish his manners or mind, but unwilling to give up his ambitions for fame, he joined the ranks of sophisticated France by attacking them, lampooning its scholars, artists and patrons, along with most of civilised France. ‘Rousseau is the greatest militant lowbrow of history’, wrote philosopher Isaiah Berlin, ‘a kind of guttersnipe of genius’.

As a consequence, Rousseau had many educated and talented acquaintances but never felt at home in France’s intellectual world. This estrangement is partly why he loved Saint-Pierre’s plants. Rousseau’s autobiographical works were filled with grateful descriptions of nature’s silence, as against intellectual chatter. The Prunella did not mock his ideas, clothes or affairs; did not gossip or slander. The plants also took his mind off the threats—real and imagined—to his reputation and security. They were a simple distraction from the complications of Parisian life. ‘An instinct that is natural to me averted my eyes, silenced my imagination and’, he wrote in his Reveries, ‘made me look closely for the first time at the details of the great pageant of nature’. For Rousseau, exiled from France, plants were a holiday from the strife of civilisation. Wary of more controversy, weary of endless bickering, Rousseau sought botanical diversions. The philosopher could eat breakfast, wander about Saint-Pierre until lunchtime, without spending a sou, or giving a second thought to another human being. And indeed, this was the middle-aged scholar’s plan for his remaining days. ‘The different soils that occurred on this island’, he wrote in his Confessions, ‘offered me a sufficient variety of plants for study and amusement for the rest of my life’.

State of Nature

But Rousseau’s botanical meditations were more than curmudgeonly retreat or cheap leisure. For him, botany was a method of perceiving, recognising and recovering what he valued most: nature. It offered him respite from restlessness and the Parisian salons, but it also helped him to rediscover nature, and the best of himself.

Rousseau’s basic belief was that nature was good. Not simply useful or beautiful—although it was both—but morally unimpeachable. In Discourse on the Origins of Inequality, Rousseau wrote that nature was the work of the ‘Divine Being’. This Being, as he wrote in a famous letter to Voltaire, was benevolent, wise and perfect. Voltaire had taken issue with the metaphysical optimism of philosopher Gottfried Leibniz and poet Alexander Pope, pointing out the common and continual misery of the world. In his famous reply, published in 1756, Rousseau wrote of the ‘invincible disposition of his soul’, which had faith in the beneficent creator, and his works. It was partly this spiritualism that caused the break between Rousseau and the more materialist, rationalist philosophes. ‘The whole’, Rousseau wrote, referring to the cosmos, ‘is good’. And because of this, all of nature was incapable of malice, cruelty, deceit. ‘Nature … never lies’, he wrote in Discourse on the Origins of Inequality. Rousseau was careful to note that nature knew nothing of ethics or politics—theoretical notions of good and evil were meaningless. But he believed nature was morally exemplary nonetheless. ‘All that comes from her will be true,’ he said, ‘nor will you meet with anything false’.

Importantly, argued Rousseau, mankind was itself honest and good, but only in the ‘state of nature’ before reason and the development of civilisation. For the philosopher, the first humans were naïve animals, lacking rationality and self-consciousness. But they were morally pure, without the catalogue of sins Rousseau attributed to modern France: ‘wants, avidity, oppression, desires, and pride’. Discourse on the Origins of Inequality’s passages on the state of nature have detailed portraits of dim, muscular but noble savages who roamed the earth in a state of primitive, isolated grace. A hundred years before Rousseau’s essay appeared in 1754, Thomas Hobbes’ treatise Leviathan also sketched out a ‘state of nature’, but his portrait was radically different: a ‘war of all against all’, in which he famously saw life as ‘nasty, brutish and short’. Rousseau launched a salvo of righteousness on Hobbes, arguing that the English philosopher was projecting the traits of modern man onto primal man. Before reason, Rousseau argued, mankind only followed two primordial principles: self-love and compassion. The first, amour de soi, kept humans alive, and allowed them to procreate: seeking food, shelter and a mate. The second, pitié, was what Rousseau described as ‘a natural repugnance at seeing any other sensible being, and particularly any of our own species, suffer pain or death’. These two principles, the work of Rousseau’s Divine Being, kept humans solitary, but also cooperative and caring when necessary. ‘Compassion is a natural feeling, which, by moderating the violence of love of self in each individual’, he wrote, ‘contributes to the preservation of the whole species’.

The end of this idyll was marked, Rousseau argued, by social intimacy and thought. Before society, there were ‘no moral relations or determinate obligations’, he wrote. Pity kept men from cruelty, but they were basically amoral: aloof, thoughtless, instinctual. But the native freedom of the noble savage was lost to the needs of the community, in which natural inequalities (brains, brawn, beauty) promoted political inequalities (class, status). This bred deceit, since, if one did not have gifts, one had to pretend to have them. ‘To be and to seem became two totally different things’, Rousseau lamented.

Rousseau’s tale of the fall of the noble savage was at the heart of his philosophy. This is why the author stressed the honesty of nature, and of man in the state of nature—the era before intelligence and community was one of brute, isolated sincerity. With thought and intimacy—that is, with society—came all the vices of modern France. Laws were introduced to overcome violence and misery, but they reinforced the rights and privileges of birth, education, beauty, wit. The poor scratched about for the basics of life, while the rich jockeyed for fame or royal favour. No-one, argued Rousseau, was happy, and all were slaves in their way:

The [noble savage] breathes only peace and liberty; he desires only to live and be free from labour … Civilized man, on the other hand, is always moving, sweating, toiling, and racking his brains to find still more laborious occupations: he goes on in drudgery to his last moment, and even seeks death to put himself in a position to live, or renounces life to acquire immortality.

The basic problem, for Rousseau, was that contemporary men were against nature. And in this, they were against themselves. They gave up their basic freedom in the state of nature to join corrupting society, and then gave it up again with unjust modern law.

Rousseau gave political and educational remedies for this malaise, each guided by his ideal of nature. In The Social Contract, for example, he speculated about the general will: the combined resolve of all citizens, with which they made the original social contract. As a united will, the citizens were sovereign, commanding magistrates to make laws that they themselves then obeyed; in this, the citizens were at once rulers and subjects. They lost their primitive freedom, but gained the security and power of political liberty. Born of the ‘very nature of man’, this general will was always right and good, and those who refused it were rightly punished.

If The Social Contract’s spirit buoyed readers with its bold republicanism, it was also vague, overly abstract and as totalitarian as it was liberal—citizens ‘forced to be free’, for example. ‘They don’t know what their true self is’, wrote philosopher Isaiah Berlin, critically summing up Rousseau’s arrogance, ‘Whereas I, who am wise, who am rational, who am the great benevolent legislator, I know this’. Rousseau, who considered himself above ordinary citizens, was too enamoured with his law-giving nature to let a citizen freely depart from its commandments.

The educational recommendations of Emile—like breastfeeding and physical learning—were fashionable amongst aristocrats (and are regularly affirmed today, albeit with more scientific support). But the overall mood of rustic simplicity was more influential than Rousseau’s child-raising advice (the Prince of Württemberg’s toddler daughter developed chilblains from walking in the snow without shoes, as Rousseau had recommended). Again, as a prophet of nature, Rousseau was more important as a figurehead or literary champion than as a practical theorist, often because his diagnoses were simplistic and his prescriptions short-sighted. But in his own life, Rousseau eventually found botany as one important outlet for his ideas.

Pure Curiosity

In his essay on inequality, after all his firebrand denunciations, Rousseau suggested playfully that his critics might abandon cities for the wilderness, but he himself was stuck with modern alienation. ‘Men like me’, he wrote, ‘whose passions have destroyed their original simplicity, who can no longer subsist on plants and acorns’, simply have to live virtuously, following the two principles of nature: amour de soi and pitié. They might try to influence ‘wise and good princes’, and Rousseau did write a constitution for Corsica. But his most common recommendation was a kind of existential retirement: away from others, toward oneself. ‘The savage lives within himself’, he wrote, ‘while the social man lives constantly outside himself’. In other words, Rousseau’s prescription was often a meditative solitude. Good men had to stay away from fame, reputation, glory and the longing for recognition. Instead, they had to stay true to their primal nature, which promised the simple, divinely given principles of goodness. ‘Virtue! Sublime science of simple minds’, he asked, in Discourse on the Moral Effects of the Arts and Sciences. ‘Are not your principles graven on every heart?’

For Rousseau, botany was one small way to rediscover these principles, by using his mind and powers of observation. In a series of letters to his friend Madame Étienne Delessert, Rousseau fleshed out these ideas. He called botany ‘a pure curiosity’, and stressed its uselessness. With quiet irony, he told Madame Delessert that it was not a particularly important occupation. ‘It has no real utility’, he wrote, ‘except that a thinking, sensitive human being can draw from observing nature and the marvels of the universe’.

To rediscover nature in this way, greater observation and analysis were important—and botany was training in both. The botanist had to look carefully. The point was not to recall Latin names, argued Rousseau, but to observe keenly. ‘Before teaching them to give a name to what they see’, he wrote to Delessert, ‘let us start by teaching them to see’. Most people, he said, never saw with sufficient clarity and discrimination, chiefly because they were wrapped up in ordinary human concerns: status, money, romance and the like. Looking at a meadow or woodland, the average Parisian simply felt some ‘stupid and monotonous admiration’, as the author put it in his Confessions. By contrast, the student of horticulture had to distinguish every anatomical detail; had to really give nature his attention. In his correspondence, Rousseau devoted a whole letter to flowers. The common daisy, for example, has a disk of tiny yellow petals, each with pistil and stamens, the female and male organs. Its white ‘petals’ are also flowers, each with a single forked pistil. What looks like a single ordinary flower is actually hundreds of tiny flowers, or florets. Rousseau then repeated this for dandelions, chicory, artichokes, thistle, pointing out the surprising details usually overlooked. His point, which echoed the counsel of Emile, was that patient, discriminating scrutiny is itself educational—it can completely change our perception. We might see the same plant every day, and be unaware of its intricacy. And suddenly, we notice more, and the novelty is rewarding. ‘Sweet smells, bright colours and the most elegant shapes’, wrote Rousseau, ‘seem to vie for our attention’. Botany is a lesson in precise, pleasurable perception. And in this, it is a remedy for the numbed consciousness of civilised life.

Having studied the anatomy of the daisy or self-heal, the botanist progresses to physiology: what are the organs for? With Madame Delessert, Rousseau used the example of a pea. The flower is like the wrapping of a gift, with four different petals all coming together. Inside this package is a little white wall of stamens, with yellow tips on each stalk. And beneath the wall, a small green cylinder: the ovary. Why these layers of petals, stamens and pod? To protect the embryonic seed, answered Rousseau. Why is one stamen detached from the rest? It withers, to leave room for the seed to grow, answered Rousseau. In this way, Rousseau did not ask what the plant could do for him—what medicine or prestigious discovery it held. He asked instead: What does the sweet pea’s flower do for the pea? What is the deeper pattern and purpose? In this, botany was a philosophical craft: a meditation on the basic physical and metaphysical principles, set down in nature by Rousseau’s Divine Being. On this, it is worth quoting the author in full, from his Reveries:

It costs me neither money nor care to roam nonchalantly from plant to plant and flower to flower, examining them, comparing their different characteristics, noting their similarities and differences, and finally studying the organization of plants so as to be able to follow the intimate working of these living mechanisms, to succeed occasionally in discovering their general laws and the reason and purpose of their varied structures, and to give myself up to the pleasure of grateful admiration of the hand that allows me to enjoy all this.

Note the breathless single sentence, which begins with economy and ends on cosmology. Here, Rousseau is lauding a kind of romantic union with nature, which overcomes the estrangement he saw in contemporary France, and in himself.

The eighteenth century witnessed a boom in horticultural discovery, cultivation and taxonomy. As the colonial powers grew, so did their herbariums and greenhouses. Acquisition, classification, exploitation: these were typically colonial pursuits. But for Rousseau, not coincidentally, this stress on usefulness was corrupt. It was destroying botany, by transforming it into a tool of human need. Medicine, for example, was blind to the beauty of the self-heal—as the name suggests, the Prunella was simply studied as a balm. By treating botany’s insights as a reward for pure curiosity, Rousseau was trying to be less ‘civilised’. Unlike his fellow citizens, he was treating the flower with a kind of naïve, selfless logic. He wrote of the ‘great system of being’ he was at one with—the ‘joy and inexpressible raptures’ of fusion with nature (that something was ‘inexpressible’ never stopped Rousseau having a good go at it).

For Rousseau, the rediscovery of these principles was also a rediscovery of himself. He believed he too had been corrupted by French society: ‘If I had remained free, unknown and isolated, as nature meant me to be’, Rousseau wrote in Reveries of a Solitary Walker, ‘I should have done nothing but good’. This, of course, was a far cry from the naïve, instinctual survival of the noble savage. But, as Rousseau himself argued, there was no going back. Botany was a simple, cheap and peaceful meditation, in which the philosopher glimpsed his better self as he scaled Saint-Pierre’s rocks.

Self-Heal

Botany was another example of Rousseau’s talent for self-portraiture. For all his concern for education and moral reform, Rousseau was more interested in revealing than restraining himself. This is why Confessions continues to fascinate readers today: it leaves the vivid impression of a man’s naked mind, complete with all its eccentricities and illusions. ‘Self-exposure, even at the cost of revealing contradictory reasoning, self-delusion, and second thoughts’, wrote his biographer Maurice Cranston, ‘becomes its own justification’. This is Rousseau’s central project.

In contrast to Confessions, Reveries and his letters, Rousseau’s writings on botany reveal the author at his most gentle, modest and reasonable: not accusing well-meaning friends of betrayal, not railing against the rich with paper and ink they purchased for him, not singing the praises of parenthood while sending his children to anonymous, orphaned misery, but quietly observing, and thinking about, plants. Botany was briefly redemptive for Rousseau, because it allowed him to exercise his gifts for analysis, description and speculation, without asking him to defend his theories or polish his facade. This was not because he had discovered the ‘noble savage’ within, but because it removed Rousseau from the crowd, and gave him something beautiful, sophisticated and animated to contemplate. Botany was not a revelation of some perfect, God-given nature, but a reflection on nature, which provided a less awkward and threatening atmosphere for philosophy. This was solitude without loneliness, intellectual amusement without company—precisely the right medicine for ‘a man unable to conceive of fraternity’, as Huizinga puts it, ‘or even of friendly rivalry’. In this, the traits Rousseau projected onto nature—naïve goodness, native isolation, psychological harmony—were actually traits he valued in himself, but which were most visible when there was no-one around to witness them. It is no coincidence that he was so taken with the self-heal—this is exactly what botany was for Rousseau: a self-administered remedy for the burdens of society, and of his own persona.