George Orwell: Down and Out with a Sharp Scythe

Outside my work the thing I care most about is gardening, especially vegetable gardening.

George Orwell, autobiographical note, 17 April 1940

George Orwell looked the part of the stereotypical intellectual: stooped, spindly, wearing ill-fitting, rumpled clothes. His face also looked un-ironed—the creases of illness and overwork (‘Wheezes like a concertina’, said a doctor of Orwell as a child). While Orwell became an iconic modern novelist and essayist, his lifetime’s illnesses were eye-wateringly Dickensian: chronic bronchitis, three bouts of pneumonia, dengue fever in Burma, haemorrhaging lungs from tuberculosis.

In the spring of 1946, Orwell had been diagnosed with tuberculosis for eight years. Instead of resting in a hospital, or ‘taking a cure’ in a sanatorium, he rented Barnhill, a house on Jura, an island in Scotland’s Hebrides. His friend Richard Rees called Barnhill ‘the most uncomfortable house in the British Isles’. Jura was equally dismal: cold, damp, remote and primitive. It was precisely where ailing Orwell was not supposed to live—a death sentence, given his infected lungs.

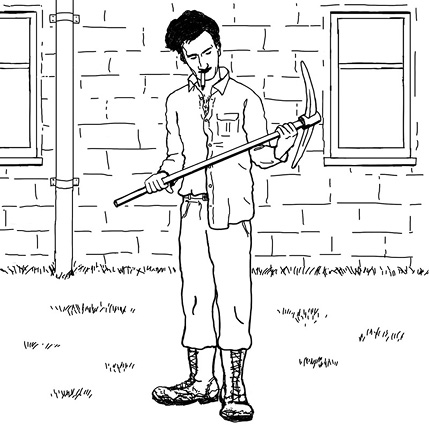

As soon as the author arrived, he continued in the same vein, what his biographer Jeffrey Meyers called ‘his self-destructive impulse’. Instead of collapsing into bed, Orwell picked up a scythe and pickaxe. He took Jura’s stony, bone-dry patches of dirt and thistles, and made a brand-new garden.

It was something of a mania for Orwell. The day after his lease began, his diary was devoted to Jura’s landscape: bush fruits, azaleas, apples, Rhododendrons, Fuchsias, bluebells and wild iris. The next day, the sick writer was digging at the soil (‘breaking in the turf’) and planning the layout (‘shall stick in salad vegetables … bushes, rhubarb & fruit trees’). When well enough to leave Barnhill, his Jura days were all like this: digging, fertilising, shooting, picking. Wheezing and aching, he planted lettuce and radishes. He knocked together a trestle for sawing logs, and a stone incinerator. He dried peat for fuel and killed a snake. And when he was too ill to step outdoors, the garden was still on his mind: ‘Snow drops all over the place. A few tulips showing. Some wallflowers still trying to flower’. He wrote those lines in December 1949, prone in his bed, his lung bleeding. They were the last in his domestic diary. He had finished typing up his drafts of Nineteen Eighty-Four, and was nearly dead from the labour. He left Jura for England that very day, and never saw his island garden again. George Orwell died in a London hospital bed just over a year later, aged forty-six.

Some Kind of Saint

Orwell had talent, a good education and ambition—but at crucial moments, he invested them in what was described by his biographers as self-destructive or dead-end pursuits. Instead of studying at Oxford, he scarpered off to Burma and joined the Indian Imperial Police. He tramped and washed dishes rather than developing a secure career. Never a soldier, he left his new wife Eileen and went to fight in the Spanish Civil War. Shot in the throat by a Fascist sniper in 1937, he convalesced back at Wallington, in Hertfordshire—not with continual bed rest, but with writing and gardening (‘We are going to get some more hens’). Less than a year later he was haemorrhaging and hospitalised. And on Jura, instead of resting his pale, broken body, the middle-aged author hacked at dry soil, 8 inches deep.

Meyer described this as Orwell’s ‘inner need to sabotage his chance for a happy life’. Troubled by chronic guilt, the author was unable to enjoy normal, middle-class contentment. He felt guilty about his privilege, his country’s inequality and imperialism, and his own absence during World War I. Of course, he wasn’t responsible for his father’s Indian Civil Service career, or his great-grandfather’s Jamaican slave-plantation profits. He did not decide on his own date of birth, too late to fight in the war. Perhaps his conscience was abnormally amplified at St Cyprian’s, where the scholarship boy was taunted by rich snobs—whom he called in ‘Such, Such Were the Joys’ the ‘armies of unalterable law’. If they lived decadently, Orwell would live austerely; if they were handsome, he would be ugly; and if they were insensitive and brutish, he would be conscientious. In short, he defined himself against their healthy, beautiful, moneyed world, and that of Eton, where he studied on a scholarship. This was the Orwell who parodied his own worst character traits in Gordon Comstock, the failed poet in Keep the Aspidistra Flying. Comstock showed promise, but warped pride kept him poor, parasitic on charity and deeply resentful of anyone who chased happiness. ‘Failure’, wrote Orwell in The Road to Wigan Pier, ‘seemed to me to be the only virtue’. He saw virtue not only in poverty, but also in dirty, banal, draining labour—like that of the hotel staff he worked with and immortalised in Down and Out in Paris and London. ‘At a quarter to six one woke with a sudden start’, he wrote of life as a kitchen hand, ‘tumbled into grease-stiffened clothes, and hurried out with dirty face and protesting muscles’. By midnight Orwell and his bed lice were back in the sack. Not the usual Etonian lifestyle.

In this light, Orwell nearly destroyed himself scything brambles and shovelling dead dirt in Jura, because he believed pain and weakness were better than idle comfort and the complicity this represented. The good life, for Orwell, was indistinguishable from gruelling, boring work. The Aspidistra of his novel was a symbol of this: the hardy house plant of lower-middle-class workers, which survives on little light and water. For the protagonist, Gordon Comstock, it signified laziness, conformity, conservatism: everything Orwell literally killed himself to avoid. Orwell was an atheist, but there was a religious fervour to this asceticism. Author VS Pritchett eulogised Orwell as ‘some kind of saint’.

Orwell also had the monk’s contempt for money, and saw gardening as a shot across the bow of expensive taste. He celebrated springtime in England as a free mass entertainment, for example. ‘The pleasures of spring’, he wrote in ‘Some Thoughts on the Common Toad’, ‘are available to everybody, and cost nothing’. And birds did not pay rent, either. Likewise, in one essay he noted that the Woolworth’s roses he planted in an old house decades before were flourishing—all this for six pence, he said with relish. This is a common tic of Orwell: noting the cheapness of good things, as an ‘up yours’ to the moneyed. Orwell ‘could not blow his nose without moralising on conditions in the handkerchief industry’, as Cyril Connolly once quipped. For Orwell, questions of beauty quickly turned to those of ethics, politics, economics. So, gardening was the perfect pursuit for a cultivated pauper.

Tripe and Vinegar

But there was more to his Jura gardening than a monastic complex. It was also a touchstone of truthfulness, what he called in ‘Why I Write’ his ‘power of facing unpleasant facts’. Whatever forced Orwell to hike the path of most resistance also increased his intimacy with real life. He was a gifted author, but what raised his novels and journalism above common reportage was first-hand experience. He knew the tramps’ aching bones, hunger and fatigue; the indignity and boredom of continually footslogging from workhouse to hostel. The Eton graduate had lived in a Parisian slum; had eaten disgusting tripe and vinegar in Wigan, Manchester. From his diary, 21 February 1936, living with a working-class family in northern England:

The squalor of this house is beginning to get on my nerves. Nothing is ever cleaned or dusted, the rooms not done out till 5 in the afternoon, and the cloth never even removed from the kitchen table. At supper you still see the crumbs from breakfast. The most revolting feature is Mrs F. being always in bed on the kitchen sofa. She has a terrible habit of tearing off strips of newspaper, wiping her mouth with them and then throwing them onto the floor. Unemptied chamber-pot under the table at breakfast this morning.

Despite his crumpled dress, Orwell was a fastidiously clean man, with an unusual sensitivity to smells. But he put up with stink, filth and blowfly corpses. He was starved, soaked, flea-bitten and shot. And though guilt compelled him, he was also driven by a lust for truth. He believed it was his duty to bear witness. ‘I write’, he said, ‘because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention’. What made this more than ordinary reportage was his willingness to live through the events he reported. And he did so without academic obscurantism or narrowing party loyalty. Hence his opposition to Soviet Russia against many of his fellow leftist peers, and despite his criticisms of Western capitalism. Orwell railed against English socialists’ blind acceptance of Soviet and Communist policies—partly on principle as a defence of liberty, but also because he had seen first-hand the brutality of Communist forces in Spain, as they attacked Trotskyist communists and anarchists. ‘I have seen the bodies of numbers of murdered men’, he wrote in ‘Inside the Whale’: ‘I don’t mean killed in battle, I mean murdered’. Instead of taking communism on faith, he bore witness and reported accordingly. What mattered were facts, and Orwell intended to find them.

This is not to say that Orwell was beyond bias. He had his prejudices: Scotsmen (‘whisky-swilling bastards’), homosexuals (‘I am not one of your fashionable pansies’) and the Catholic Church (‘my obsession about R.C.s’). He could be petty, short-sighted and nasty in his prose. In Down and Out in Paris and London, for example, he produced caricatures of canny, greedy Jews. ‘It would have been a pleasure’, he wrote of one second-hand-clothing seller, ‘to flatten the Jew’s nose’. But bigots rarely grow out of their bigotry; to his credit, Orwell let experience change his mind. Over a decade later, with Hitler in power and millions of European Jews being slaughtered or driven to death in work camps, Orwell offered an authoritative, passionate critique of anti-Semitism. In the intervening years, the author had met many more Jews, and revised his earlier mistakes.

In this way, Orwell was the first to recognise errors of logic and fact, including his own blind spots. As a journalist, critic and novelist, his outlook was unusually contingent upon evidence, and he continually returned to particulars, details. This was a Herculean achievement, given his turbulent political era. Orwell fought passionately for his worldview—on paper and in Spain—without transforming it into the dogma of his communist and nationalist peers. In this, the author was more scientist than prophet, with a scientist’s respect for facts, sceptically handled. Orwell, it could be said, lived experimentally.

With this scientific mindset came a respect for transparency of language. Having seen first-hand the brutality of Spain and the squalor of Paris and northern England, Orwell had no time for fancy words or high theory that obscured the facts. Hence his now famous defence of clear writing in works like ‘Politics and the English Language’, and the appendix on Newspeak in 1984. Orwell argued that poor language was tied up with poor thinking. Muddled thoughts led to muddled phrases, which may seem pretty, but do nothing to illuminate the writer or reader—leading to more dubious ideas. Language, he wrote in his own typically concise prose, ‘becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts’. For Orwell, the ability to write and think clearly was a moral responsibility. Without this clarity, words may string together nicely, but they are false.

In the appendix to 1984, Orwell went further, describing the deliberate perversion of thought for political gain, by eradicating the richness of language. ‘The purpose of Newspeak was not only to provide a medium of expression for the world-view,’ he said in frighteningly cool phrases, ‘but to make all other modes of thought impossible’. Orwell’s insight was taken directly from the twentieth century’s oligarchs and tyrants, who ‘don’t advertise their callousness, and … don’t speak of it as murder’, he said in ‘Inside the Whale’: ‘it is “liquidation”, “elimination”, or some other soothing phrase’. And it was not only the Nazis and Stalinists who did this; their English apologists also distorted the truth with sterile jargon. In ‘Politics and the English Language’, he referred to a university professor who was defending Soviet totalitarianism. ‘A mass of Latin words falls upon the facts like soft snow,’ Orwell wrote, ‘blurring the outlines and covering up all the details. The great enemy of clear language is insincerity’. Orwell did not live to hear torture described as ‘enhanced interrogation technique’ or state-sanctioned rape as ‘mandatory trans-vaginal ultrasound’, but he would have recognised the bullshit immediately.

Mr Orwell: Author, Gardener, Scientist

The gardens of Wallington and Jura were at the heart of Orwell’s scientific attitude and rewarded his dogged search for truth. This is because horticulture is first and foremost a realist’s enterprise: it requires practical candour. A mistake with harsh frosts, for example, cannot be hidden with Politburo spin; the crops simply die. Likewise for soil, sunlight, humidity, acidity: they have tangible consequences. The labour is also unavoidably tactile: freezing mud, sharp brambles, nibbling ticks. When Orwell wanted to cultivate Jura’s ‘virgin jungle’, as he put it, he had to suffer cold, cuts and itches. He did not want to escape from reality; he wanted to dwell in facts, however painful.

This sounds dull, but it came with genuine delight. Witness Orwell’s pleasure at cheap Woolworth’s roses: ‘A polyantha rose labelled yellow turned out to be a deep red. Another, bought for an Albertine, was like an Albertine, but more double, and gave astonishing masses of blossom’. His diaries too were full of these discoveries. Orwell put frog spawn in a jar, just out of curiosity (they died, perhaps for want of fresh water). He made a mustard spoon from bone, and a salt spoon from a deer antler (‘Bone is better’). He compared sickles and scythes for cutting rushes, and tested the right cutting angle. For Orwell, gardening was more than self-flagellation. Like all his adventures, it was an experiment—a chance to get more intimate with the facts.

As an experiment, the author’s gardening was an exercise in what’s called epistemology. That is, it concerned how we know what we know, which was fundamental for Orwell. Jura’s strawberries or Wallington’s lettuces did not necessarily contain some particular, predetermined truth for the author—some definite vision of man or universe. Instead, the garden was a laboratory, in which Orwell’s relation to truth itself was tested. It yielded knowledge about Albertine roses or sweet Williams (‘sometimes “shoot up” … but cannot be made to do so’), but it also yielded knowledge about knowledge—an outlook on reason and evidence, which recognised their strengths and weaknesses. Orwell referred to this as the ‘scientific method’, but he did not yearn for some utopian technocracy, populated and run by physicists and chemists. Quite the contrary. He wanted to cultivate, as he put it in The Tribune, ‘a rational, skeptical, experimental habit of mind’, for which muddy gumboots were as fundamental as a typewriter. Orwell was something of a masochist—playing scientist with a hacksaw instead of convalescing in bed. But he was also rightly passionate about the search for truth, what he called ‘a method of thought which obtains verifiable results by reasoning logically from observed fact’. Faced with damaging political and military conflicts between uncritical dogmatists of every stripe—communists and capitalists, anti-Semites and Zionists, nationalists and imperialists—Orwell believed that the only hope lay in decent reason: a more careful, critical approach to truth. And he discovered this method, at least in part, in his home-built sledgehammer and a well-sharpened scythe.

For all his Etonian sangfroid, Orwell was a haunted, passionate man, who overcame frailty with impressive mental and physical labours. He had grit. And his distinctive approach is still relevant today: a familiarity with palpable reality, sceptically treated. Much of contemporary life has an atmosphere of taken-for-granted certainty to it—the conceit of flawless knowledge in key performance indicators, economic cycles, political polling, intelligence tests. What philosopher Alfred North Whitehead called ‘the fallacy of misplaced concreteness’—abstractions dressed up as robust facts—is common. And this facade of perfection is regularly chased in public and private life: political slogans, psychological profiles, religious texts. It comforts us, by making life seem less uncertain and unsettling. For those with a sufficiently sceptical attitude, the garden can be a remedy for this delusion—a reminder of how subtle, changeable and complicated reality is. As Orwell discovered, ‘seed plus soil plus rain plus sunshine’ can be a surprisingly complicated equation, when calculated in the field. The garden is where hypotheses are only cautiously upheld—until tomorrow, when they are falsified as some unexpected variable wilts the lettuce, shrinks the gooseberries. An Orwellian garden instructs its devotees not to cling to familiar but false ideas; to be wary of all-too-perfect theories. No wonder the author of 1984 prized his gruelling Jura labours: they were a brief liberation from the totalitarian mind.