For Chavoret Jaruboon, the hardest part of being on the execution team at the country’s biggest maximum-security jail was walking into the death-row cell to tell the prisoner that he was about to be executed. “Whatever crimes the person had committed, they were still heroes to their families,” said the former chief executioner of Bang Kwang Central Prison. “The inmates had time to write a letter to their family, and have a last cigarette and a meal, but they usually didn’t feel like eating. They were also given the chance to see a Buddhist monk for a final blessing.”

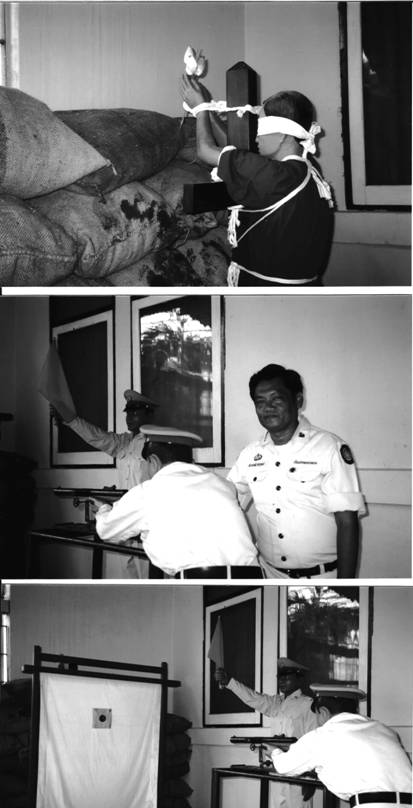

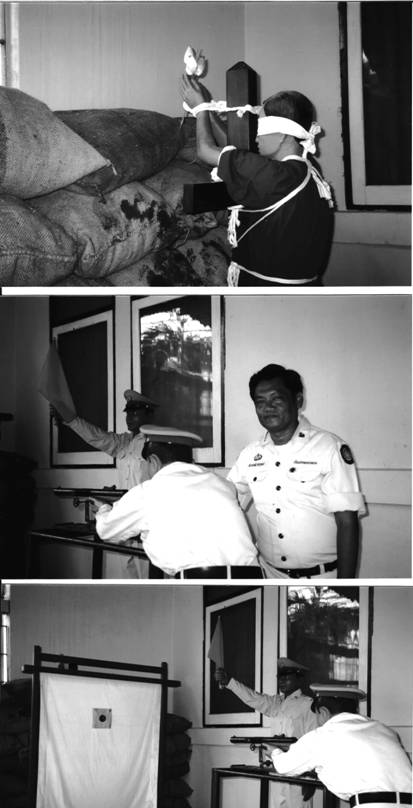

Blindfolded, and with chains around their ankles, the condemned man or woman would be escorted by guards into the death chamber. There, their hands were tied together with the sacred white thread that monks use to bless devotees and to ward off evil, so they could clutch three unopened lotus blossoms, three joss-sticks and a small orange candle, as if they were going to pray at a Buddhist temple. While Chavoret waited behind the gun, the guards would then tie the inmate to a wooden cross with his hands above his head, and put a white screen between him and the machine-gun, which was bolted to the floor and pointed at his back. Finally, a doctor put a target on the screen where the prisoner’s heart was, so the executioner could take aim and fire.

That was how the death penalty was carried out after the government outlawed beheading in 1932, and before Thailand switched to lethal injection in late 2003.

Chavoret recalled the condemned men and women being led in to the chamber. “I heard it all—crying, begging and cursing. But some of them just walked in without a word. They were ready to die.”

Until being diagnosed with cancer in 2010, these were the kind of tales that the former rock ‘n’ roll musician recounted for rapt audiences at Thai universities and remand centres for juvenile delinquents, which he also included in his 2007 autobiography, The Last Executioner.

Until recently, Chavoret also volunteered as a tour guide at the Corrections Museum once a month. The museum is on the grounds of Romanee Lart Park, not far from the Golden Mount and Khaosan Road in Bangkok. On display are knives and syringes made by former inmates, along with implements of torture once used in Siamese jails. On the ground floor, there’s a huge rattan ball—like the ones used in takraw, the Asian version of volleyball—with sharp nails protruding from the inside. Curled up inside the ball is a mannequin of a prisoner. To punish the inmates or amuse themselves, the authorities would let an elephant kick the ball around. After it got bored, the tusker would often trample the bloody ball and squash the prisoner. This type of torture (and others like it) was outlawed by King Rama V at the end of the 19th century.

Filled with flowerbeds, shrubs, joggers and school kids, the park was once the site of Bangkok’s most draconian jail, as evidenced by the vacant row of jail cells on the north side and the guard towers that stand like stone sentinels. Built by the French at the end of the 19th century, most of the Maha Chai

These tableaux of execution scenes, including the original machine-gun used to execute inmates at Bang Kwang Central Prison, are on permanent exhibit at the Corrections Museum. Also pictured is Chavoret Jaruboon, the last executioner.

penitentiary was demolished in the 1980s. Some of the inmates were transferred to Bang Kwang Central Prison, such as convicted heroin trafficker-turned-author Warren Fellows who did ‘hard time’ in both penal facilities, and wrote an autobiography about his experiences titled The Damage Done: 12 Years Of Hell In A Thai Prison.

To punish certain convicts, he wrote, they were locked in a ‘dark room’ for 23 hours and 55 minutes a day. These hellholes were so cramped there was not even enough room for all of them to lie down, so they had to take turns sleeping. Left there for months at a time, he and his fellow inmates caught cockroaches and mashed them up with a little fish sauce to supplement their meagre ration of one bowl of gruel per day. During one such punishment stay, the author recalled hearing a scratching noise that went on for hours. It turned out to be a Thai inmate sharpening a nail so that he could attack another prisoner. Screams bounced off the walls as he stabbed his victim again and again, but the guards did not remove the corpse until the next day.

In his autobiography, which remains a perennial bestseller on the backpacker trail in Southeast Asia, the sadism of the prison guards goes far beyond anything in the book and film that raised the bar for the foreign-jails-are-hell genre—Midnight Express. In one particularly nauseating episode, Fellows (who was first imprisoned at Maha Chai in the late 1970s) wrote how a guard forced a bunch of the convicts to stand in a septic tank, chin deep in excrement for many hours, because they’d been playing a dice game in their cell.

The popularity of his book has had some positive effects, such as the banning of the ‘dark rooms’. The prison’s former director Pittaya Sanghanakin took great pains to announce some of these improvements at what must have been the most bizarre anniversary celebration ever held at any correctional facility. In 2002, Bang Kwang Central Prison—located just outside Bangkok in Nonthaburi province—celebrated its 72nd anniversary (an auspicious occasion given the 12-year cycles and 12 different animals in Chinese astrology). The Corrections Department set up a stage across from Bang Kwang for Thai bands, retinues of sexy female dancers, comedians and beauty pageant contestants. Commenting on the festivities, Pittaya said, “The people around here have supported us, so we wanted to do something in return for them.” Up and down the roads near the jail, scarecrows wearing the prison’s blue uniform, straw hats and happy faces had been tied to power poles. “Since the inmates are not allowed out of their cells,” Pittaya said, “we thought that they could enjoy the festivities through these effigies.”

For many of the foreign inmates watching the events unfold on closed-circuit television, the celebration was a kind of torture. One of them, who asked to remain anonymous, said, “What’s there to celebrate? Seventy-two years of injustice?”

For many of the locals visiting the two-day party, the biggest lure was the display of archaic torture instruments, complete with life-size mannequins, on loan from the Corrections Museum. These included the original machine-gun used at Bang Kwang, a tableau of two machete-wielding executioners dressed in red outfits about to lop the head off a blindfolded prisoner, and a mannequin whose arms and legs were locked in a pillory so splinters could be hammered under the nails of his hands and feet. Watching families, beauty queens and rich matriarchs walking their poodles past these exhibits was a crash course in the country’s bizarre contrasts.

Perhaps these exhibits were intended to show how much more humane the prison system has become. Aside from some of the improvements, such as introducing bachelor’s degree correspondence courses (with instructors coming into the jail to oversee the final exams), the director said the biggest problem facing the Thai penal system was overcrowding—to the point where cells at Bang Kwang intended for four people actually hold twenty. In the early 1990s, there were 90,000 prisoners doing time in Thailand. Now there are three times that many (around 70 per cent on drug-related charges). The Corrections Department has been trying to decrease these numbers, he said, by arranging early releases for the elderly and those serving less than 30 years.

Only a few days after the jail’s anniversary, however, Amnesty International filed a report titled ‘Widespread Abuses in the Administration of Justice’ in Thailand, accusing warders of severely violating prisoners’ basic rights, and using torture as punishment for minor infractions. The report cited an incident in May 2001 where a Thai inmate named Sinchai Salee was punched, kicked and smacked with batons by several guards until he lost consciousness and eventually died. Earlier, the 30-something Sinchai had got into an argument with a guard because he wanted to nail a water bottle to the wall of his cell. Amnesty reported that many of these punishments were doled out by ‘trusties’—other inmates who receive special privileges from the warders in return for keeping, and sometimes disturbing, the peace. The report also noted that, in direct contravention of Thai law, the men on Bang Kwang’s death-row have to clank around with heavy leg irons on 24 hours a day. These shackles are welded together.

When the Corrections Department admitted for the first time ever that some of these abuses were true, the story made front-page news in Thailand. Siva Saengmanee, the Correction Department’s director-general at the time, said they had received numerous complaints about warders ruling over their charges with iron fists and guards extorting money from prisoners or demanding sexual favours from visiting wives and daughters.

“It is the responsibility of prison officials to turn convicts into valuable members of society, not ruin their morale by handing out unauthorised punishments,” Siva said during a press conference.

In The Last Executioner, Chavoret blamed the persistent problem of corruption in the prison system on the poor pay the guards bring home—a rookie only makes about 7,000 baht a month—and pointed out that some guards have been punished and wound up in prison. A case in point is Prayuth Sanun. To supplement his meagre wage, he began working as a bouncer in a bar, where he fell in with a gang of drug-dealers. Nabbed with 700,000 methamphetamine pills, an M16 and a load of cash, the former guard has now languished on death row for nearly a decade.

Although he has never downplayed the corruption of some guards, Chavoret said there have been some genuine moments of levity and compassion prior to executions. One example he cited was of a Thai woman who had been arrested 12 different times for trafficking in narcotics before finally getting the death sentence. When the female guards escorting her to the chamber—that bore a sign in Thai euphemistically referring to it as the ‘room to end all suffering’—could not control her, a male guard stepped in to hold her hand, asking if he could be her last boyfriend. That made her laugh and she kissed him on the cheek. Arm in arm, the guard escorted her on a blind date with death.

The former executioner often resorted to Buddhist teachings to soothe the infuriated men sentenced to death. In the case of the serial rapist Sane Oongaew, that showed remarkable restraint on his part. Sane and several cohorts raped and strangled a ten-year-old girl to death in Samut Prakarn province back in 1971. The autopsy report revealed that she was covered with bruises and abrasions, her hymen had been shredded, semen clogged her vagina and clay had been stuffed down her throat all the way to the larynx. Sane’s cohorts confessed, but he steadfastly denied any complicity in the sex crime and homicide. When the superintendent read out the execution order to him, Sane screamed, “I didn’t fucking do it! I don’t know a goddamn thing about it. I will haunt you all for the rest of your lives. Let me see the face of the detective in charge! Where’s the son of a bitch?”

Chavoret walked over to remind him of the Buddhist teaching about thinking positive thoughts before you die so as to be reborn in a better place. “Just think of it as bad karma coming back to you for what you have done. If you are positive when you ‘go’ you will end up in a better place, so empty your mind of anger and negativity.” That calmed him down a little. For a last will and testament Sane wrote a letter to his father, repeating the Buddhist tenet that the only certainties in life are birth, ageing, pain and death, while reminding him to visit his brother Narat who had confessed to his role in the rape and murder.

“Dear Dad,

“I just want to say goodbye to you. I hope you won’t be too sad. Just think of it as a natural occurrence. We’re bound to be born, age, be hurt and die anyway. Please look after my wife and don’t let her struggle. Tell her not to take another husband. Don’t bury my body, keep it for three years. Don’t forget, dad, to visit Narat as often as you can.”

Much of the violence in Thai jails, the former executioner said, is the result of chronic under-funding. The daily food budget is still less than one US dollar per day. Without money coming in from relatives and friends for inmates to buy food in the prison shops (usually run by gangsters continuing their lives of crimes from the other side) and medical supplies, inmates are prey to starvation and opportunistic illnesses. They also end up doing odd jobs for other inmates—sexual services included—to make ends meet.

For many of the 700-plus foreign convicts incarcerated in Bang Kwang, the country’s largest maximum-security penitentiary (population: 7,000), the worst part of prison life is the boredom. Visits from tourists are reprieves from that tedium. Partly because of the popularity of Warren Fellows’ memoir, Bang Kwang has become a strange stopover for travellers.

Garth Hattan, the former rock drummer and convicted heroin trafficker who served eight years there, said the inmates refer to some of the visitors as ‘banana tourists’ “because they make us feel like monkeys in a cage. Some women even asked me to take off my shirt for them, or they say shit like, ‘How could you have been so stupid?’ Some of them have also asked me to where to score drugs or how to set up deals.”

The magazine columns Garth wrote are crammed with similar tales and bytes of humour rare in the prison genre. One guard, trying to suck up to a former security chief Garth described as the ‘evil love child of Pol Pot and Imelda Marcos’, discovered a stash of what looked like marijuana in Garth’s locker. The guards rolled up ‘bombers’ to test the weed, which turned out to be green tea.

Many of the inmates, particularly the poor Asians, have to work inside the technically illegal sweatshops or do laundry and perform sexual favours for the other inmates. “You may assume that being indigenous to Thailand, kathoeys (ladyboys) would be the sole purveyors of the prison sex trade, but you’d be amazed to see what levels some ostensibly normal guys have plunged to just to get a little extra chicken with their rice. It’s as if walking through these gates, no matter how turbo-hetero they claim to be, gives them a license to—poof!—turn into ‘Bang Kwang Barbie’ (Malibu Barbie’s twisted Siamese sister),” wrote the Californian in another column.

The prison authorities knew that Garth’s then-fiancée, Susan Aldous (also known as ‘The Angel of Bang Kwang’), was smuggling his columns out to be published in our magazine, but they didn’t mind because he included enough cautionary anecdotes about mixing high times with lowlifes to deglamourise prison life and the backpacker chic of doing drugs in Thailand.

“There’s a message in here somewhere and it’s not just targeted at you hell-man adventure cowboys, and you ennui-plagued, insouciant heiresses-in-waiting who are out to shock the world—maybe your parents—by taking the fateful walk from the conventional wild side into something you feel exudes a truly radical allure—like an impulsive jaunt into narco-trafficking, for instance.

“There’s no glamour here, no promise of success, no proverbial pot of gold to pick up on the other side, just a sweaty inanimate existence riddled with the futile dreams of what could’ve been, mingled with the aching regret of having let so many good people down—especially yourself. Enjoy your travels, and never put yourself in a position that would jeopardise your freedom to do so.”

In recent years, the number of ‘banana tourists’ and backpackers has declined, said Susan. “The prison authorities have made it more difficult to visit inmates so you don’t see so many of the Khaosan Road types, or the messages on notice boards in guesthouses about visiting prisoners. If you want to visit an inmate now you have to dress up a little and act like a friend or relative.”

Transfer agreements between many Western countries, and more recently with Nigeria, have ensured that there are less black and white men in the jail. “The atmosphere at Bang Kwang has changed in recent years,” noted Susan, “because of all the transfer agreements, but there’s a lot more inmates from Laos, Vietnam and Hong Kong who tend to blend in and are forgotten. Their governments don’t care and they don’t get much attention.”

Until a few years ago, African men made up the overwhelming majority of foreign prisoners. When I visited a 25-year-old Nigerian inmate, who had been sentenced to 50 years for serving as a heroin courier, or ‘mule’, he told me, “Compared to life in Nigeria, this prison isn’t so bad. Some of the crime syndicates we work for make a special deal with our families, so if we get caught the syndicates give our families about 20 dollars per month for the time we serve in jail. In Nigeria that’s not a bad income. At least I can feel like I’m still taking care of my wife and three children.”

Beautifully landscaped with flowers and hedges, the visiting area demonstrates the Thai penchant for painting the happiest of faces on the grimmest of backdrops. Recently, the authorities have also put in plexi-glass and telephones, which, if the connections were better, would make it easier to talk to a prisoner. It’s an improvement from the old days of having to yell through a pair of wire fences separating a four-metre gulley in the midst of ten other yelling matches. During one such visit, Garth shouted, “This place is still hell, but it’s nowhere near as bad as it was when Warren Fellows was here. A few of the older dudes and guards remember him as being a terrible junkie.”

Garth and Warren are not the only ones who have turned headlines into bylines. A glut of prison memoirs has emerged from Thailand, such as Susan Gregory’s Forget You Had a Daughter, Debbie Singh’s You’ll Never Walk Alone (her brother received ten years in jail for fencing a check worth a thousand dollars) and a few forgettable films like Brokedown Palace—principally shot in the Philippines with Claire Danes and Kate Beckinsdale as the leads—in addition to an Australian mini-series for TV called The Bangkok Hilton featuring a young Nicole Kidman.

All of these shows and books play excruciating variations on the Thai-jails-are-hell theme. The only book to break out of that creative cellblock is David McMillan’s Escape. Believed to be the only Westerner to ever successfully escape from the ‘Bangkok Hilton’ (a nickname give to many Thai jails, but in this case Khlong Prem), McMillan (a pseudonym) comes across as a pathological criminal and unrepentant drug dealer who, nonetheless, pulled off a death-defying escape that required as much cunning as courage a decade before the book came out in 2007. After sawing through the bars of his cell window, he used a piece of wood and straps to abseil down the wall. He bridged an internal moat with a ladder he’d made out of bamboo and picture frames, which also allowed him to scale an electrified fence. By dawn he was creeping across an outer wall, using an umbrella to shield his face from the guards up in the watchtowers. If he had been spotted, chances are he would’ve met the same fate as the four Thai inmates who commandeered a garbage truck inside Khlong Prem Prison in 2000. As they tried to ram their way through the front gates, the guards shot all four of them.

Richard Barrow, the British expat who runs the largest collective of English-language websites on Thailand, posted a map of the escape route on the Paknam Web Network. In an interview he did with the author, MacMillan told him, “Every element of good fortune became essential: the existence of an army-boot factory for the rope; the paper factory for the long bamboo poles—even the umbrella factory, as I’m sure I would have been spotted by the tower guards without that umbrella shielding my pale face.”

Using a fake passport, MacMillan fled the country after serving three years in Khlong Prem. Having done ten years in an Australian jail and other stints in prisons across Asia, he said, “I’ve been in worse prisons [than Bangkok]. By that I mean terrifying. There was two months in solitary in Pakistan when I was fed only watery beans poured through the bars with a piece of roof guttering, for the solitary door was never opened.”

The book that may blow these all away is slated for release in late 2010. A Secret History of the Bangkok Hilton is a collaboration between Pornchai Sereemongkonpol and Chavoret Jaruboon. Pornchai has dug deep into the pits of the prison’s history to excavate more than a few buried skeletons, as well as provide an overview of the Thai judiciary and the beheading ritual, and personal letters from death row convicts. Now that Chavoret has retired from the prison and has terminal cancer, the book is kind of a last will and testament for him. Of all the characters that have populated Bang Kwang over the last eight decades, he remains one of the most colourful and contradictory.

Growing up in the Bangkok neighbourhood of Sri Yan, the son of a Buddhist father and Muslim mother, as a boy Chavoret had to walk past a brothel that doubled as an opium den on his way to a Catholic school. Learning English from his father’s collection of albums by Frank Sinatra and Hank Williams, he played guitar in a series of rock ‘n’ roll cover bands that entertained the GIs all over Thailand. True to his self-deprecating wit, he said, “I was never that handsome or talented and I needed a steady job with a government pension to support my family.” His musical talents were more noteworthy than that. Some of the journalists or relatives of prisoners coming to Bang Kwang would be treated to his soulful versions of sob songs by Hank Williams or upbeat rockers by Elvis, sung in a rich baritone as Chavoret finessed the fretboard of an acoustic guitar he always kept in his office.

Ironically, the man who executed 55 inmates over 19 years has also been hailed as a prison reformer. Susan—the ‘Angel and She-devil of Bang Kwang’—recounted, “If it wasn’t for Chavoret helping me with the paperwork and dealing with all the bureaucracy, I wouldn’t have been able to do half of what I’ve done here. You’d think the inmates here would hate him, but he’s very well-liked and respected.”

On one occasion, Susan was visiting a group of older Thai inmates serving life sentences—many of them hadn’t had a visitor in years—and she went over and hugged a man covered in sores. “Out of the corner of my eye, I saw Chavoret shed a few tears. He’s a bit more of a softie than he lets on,” she said, “and I think he’s dealt with the guilt of his old job by drinking a lot.”

Pornchai, his co-author, drew a different bead on this complex character. “He’s not really a man given to introspection. So I don’t think he dwells too much on his old job. But I have been pleasantly surprised by the way he’s handled his cancer diagnosis. He’s still in good spirits and sometimes he invites me out for a steak dinner.”

While we were sharing drinks and dinner with Chavoret one night in a restaurant overlooking a pond filled with water lilies, his wife of 30 years joined us at the table. Tew said, “At home he won’t even kill ants or caterpillars. He has a good heart and we never talk about the prison at home.”

Chavoret took a banknote out of his wallet and handed it to her. Everyone at the table laughed. “We’re always joking around like this,” he said. “That’s what keeps our marriage fresh and the friendship has kept us together for this long.” Later on, he insisted on paying the tab for everyone at the table.

In his early years at the prison, some of the misfires he witnessed in the ‘room to end all suffering’ would have sent more sensitive souls on a one-way trip to the madhouse. Such was the case with Ginggaew Lorsoongnern, a nanny who kidnapped the son of her wealthy employers. When the ransom money did not materialise, her two male accomplices stabbed and buried the boy while he was still alive. To ward off any threats of a haunting, the killers (just like the guards in the death chamber) put flowers, incense and a candle in the boy’s hands before tying them with the scared white thread monks use to repel evil.

Ginggaew did not participate in the murder, but she was sentenced to death in early 1979, along with her two accomplices. The young woman struggled all the way into the death chamber and kept struggling as they tied her to the cross. The executioner fired ten bullets into her back and the doctor pronounced her dead. But as they brought one of her accomplices into the room, Chavoret and the guards heard her scream in the tiny morgue. Not only that, Ginggaew was trying to stand up. Pandemonium ensued. One of the escorts rolled her over and pressed down on her back to accelerate the bleeding and help her die,” wrote Chavoret. “Another escort, a real hard man, tried to strangle her to finish her off but I swept his arms away in disgust.”

Even after they executed one of her accomplices, the doctor found that the woman was still breathing. He ordered the guards to tie her back on the cross and this time they used the full quota of 15 bullets to ensure she was dead.

That was not the end of it. Pin, her other male accomplice, was still breathing after the first round of 13 bullets and had to have ten more shots.

Chavoret and the rest of the guards were all struck by the fact that Pin and Ginggaew had suffered much the same fate as the little boy they had stabbed and buried alive. It was karma, they decided. The boy had choked to death on dirt. The man and woman had choked to death on blood.

After a decade of helping the prison authorities by serving as an escort or one of the men who tied the inmate to the cross, Chavoret received an official order to become the chief executioner in 1984, a job he did not want and only took to earn more money to support his wife and three children.

Before pulling the trigger, he would pray to a powerful spirit for absolution, explaining that he was not killing the person out of malice, he was just doing his duty. “I had no power in the judicial process. After the police, the witnesses and the judge all had their say, I was just the final link in the chain.”

Afterwards, he would go out drinking with his fellow prison officers in order to ward off the guilt and the haunting sensation that the dead person’s spirit was shadowing him. He was paid 2,000 baht for each execution, money which he religiously donated to a Buddhist temple to make some merit for himself and the condemned men and women. The temple’s abbot was stunned to find out that one of his most regular donors was a man who had broken the first precept of not killing any life forms time and time again. When Chavoret asked him who should shoulder the blame for these executions, the abbot responded by repeating the Buddhist belief in the interconnectedness of life. “It’s everyone’s fault: society, the government, the laypeople, the criminals, television, poverty, hopelessness, desperation, anger, greed—everything and everyone is at fault.”

In person and in his book, Chavoret has detailed the many improvements at Bang Kwang. Paramount among them is a new breed of guards, who must now have a university or college degree, unlike the old days when a fair number of the guards had no more than six or seven years of basic education. The new recruits have brought with them a bevy of new projects, from boxing matches and vocational programmes to more correspondence courses and workshops.

The medical facilities have also gotten better. When Susan first began undertaking projects there in the mid-1990s, the ramshackle ‘hospital’ had no mattresses or wheelchairs, no dental care or even aspirins, and the medical budget per year was less than US$3,000 dollars for 7,000 prisoners. “If you got sent to the hospital back then, it was assumed you would never get out again. Many inmates died on a metal frame covered with bare boards, but the mattresses we put in are still there and the conditions are much more hygienic now, and they’ve got a proper doctor and dentist. If their families and the embassies push, the prisoners can get prescriptions filled and even anti-viral drugs for HIV and AIDS. The conditions still aren’t great, but they’re much better than before,” said the altruist, adding that conditions have also improved in many of the homes for orphans and the elderly and disabled where she has worked. “Thailand has made incredible progress in the last 30 years.”

For all the pros, however, there all still plenty of cons. For one, the legal system is as corrupt and haphazard as ever. In many surveys of Southeast Asian countries, only Burma and Indonesia consistently rank lower than Thailand for corruption in the judiciary system.

“If you sentenced me to an indefinite sentence, even in a five-star hotel with congenial company,” said Susan, “it would still be hell. But the kind of indefinite sentences they give out here are completely arbitrary and the punishment rarely fits the crime. The police force is corrupt, the evidence is tainted, the judges rotate, there’s no juries, or background checks or extenuating circumstances that look into poverty and ignorance. What can you say about a justice system where a 75-year-old man who accidentally killed a friend in a drunken argument gets sentenced to 104 years and six months in jail, while a real murderer gets out after a few years because he’s got the right contacts?”

Drug dealers continuing their lives of crime from behind bars and substance abuse are two other plagues that continue to poison the populace of Thai prisons. As former inmates and heroin-traffickers Garth Hattan and Warren Fellow have said, it is a tragic irony that the drugs which landed them (and many others) in jail, or on death row, are widely available to inmates at inflated prices.

The current director-general of the Corrections Department, Chartchai Suthiklom, held a press conference in 2010 to announce that they have installed mobile phone signal jammers in jails in Ratchaburi and Nakhon Ratchasima provinces to stem the flow of drugs. He said that guards have found mobile phones hidden in hollowed-out books, thrown over prison walls and wrapped in condoms found in prisoners’ sphincters after court appearances. With a phone, the drug dealers can set up deals from behind bars and have the money transferred into their bank accounts by relatives. The dealers also vie for cuts of the lucrative prison market, where drugs sell for up to five times the street price. Of the 210,000 convicts incarcerated in Thailand, the director-general estimated that around half are addicted to drugs, primarily methamphetamines.

For human rights advocates, however, abolishing capital punishment is at the top of their agenda. That seemed like a probability after Thailand switched to lethal injection at the end of 2003. Earlier, former director Pittaya and a task force had visited Texas—which has more inmates on death row than any other state— to observe an execution. The former director of Bang Kwang said, “A muscle relaxant and sedative is given to the convict shortly before they inject him with the lethal dose so he’s already asleep and doesn’t have any convulsions. It’s a much more humane form of capital punishment and only takes about four minutes in total.”

After three convicts were executed in late 2003, the courts were still handing down death sentences (mostly for trafficking in methamphetamines), but there were no more executions until 2009, when two middle-aged men Thai were executed by lethal injections. In the media blitz that followed, some inmates have alleged that prisoners are paying ‘life insurance’ to authorities, anywhere from 1,000 to 5,000 baht per month, so that their names do not come up next on the list.

Although Chavoret believes that capital punishment has not caused the crime rate to decrease, he insisted that it’s still necessary in Thailand, citing the example of one of the two Thai women he executed.

“She had a long history of previous offences. She killed an infant and packed its body full of heroin—the same technique some American GIs used to use with their dead comrades to export the drug into America—and then she tried to carry the dead child across the border to Malaysia. What can we do with people like this?” he asked rhetorically.

He had a point. What did the parents of the child who was used as a drug courier’s ‘doll’ think was just punishment? What about the family members of the ten-year-old girl raped multiple times by three different men, or the boy who was buried alive and choked to death on dirt? Would they not feel justified in wanting to see the killers of their children and siblings receive the maximum possible punishment for those unspeakable crimes?

In theory, the reasons for abolishing the death penalty are clear enough. In reality, the issue is stained with too much blood and clouded by too many warring emotions impossible to codify in the heartless terms of legalese.

Asked if he was happy to see death sentences being executed with needles instead of firearms, Chavoret said, “Sure, I’m happy about it. It’s more humane and I’ve never liked guns and never had one at home. Besides, I’m going to go down as the last executioner in Thai history.” He cracked a grin and laughed.

True to the festive Thai spirit, the change to lethal injection occasioned another party at Bang Kwang Central Prison, not dissimilar to the 72nd anniversary celebrations held the previous year. For the TV cameras, celebrity pop stars jammed on-stage, ladyboy dance troupes kicked up their heels and smiling prisoners waved flags, as a group of monks sprinkled holy water on the machine-gun to ‘purify’ it. They then released more than 300 balloons to symbolise the spirits of all the condemned men and women who had lost their lives in the ‘room to end all suffering’. By all appearances, it was another jolly and ritualised occasion in the land of contradictions where the justice of karma, not jurisprudence, overwrites the letter of the law.