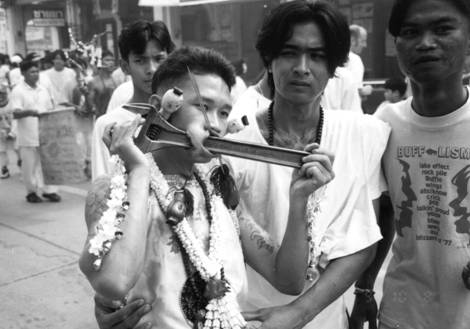

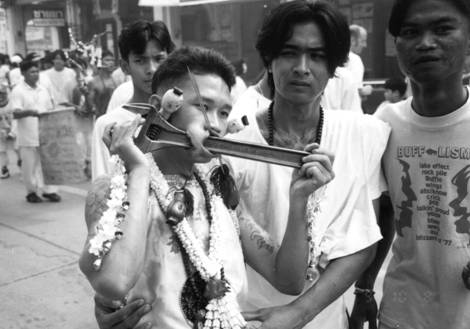

A young male traveller with a radioactive-looking suntan, colourful tattoos and enough earrings to set off an airport metal detector stepped out from behind a new Toyota, snapping a shot of a Thai man who had a metre-long sword pierced through both of his cheeks. Behind him was a Kodak photo shop, an ATM machine and the off-white façade of one of Phuket’s oldest examples of Sino-Portuguese architecture, the On On Hotel.

This bizarre juxtaposition of the modern and the primitive is the most photogenic feature of Phuket’s annual Vegetarian Festival. These Taoist Lent celebrations are held in some of the southern provinces of Thailand for nine days during the 9th lunar month of the Chinese calendar. Of all these movable feasts, Phuket’s is the grandest.

Throngs of tourists crowd the sun-glazed streets for the processions on the last three days of the festival. In particular, a healthy contingent of rich Chinese fly in for the festival, as this is the only part of the world where Taoist Lent is celebrated with such colourful and grisly abandon. While the snap-happy tourists gawk in disbelief and take photos, the mah song—‘entranced horses’—willingly stop and pose for them. The faces of these Thai men, women and even a few transvestites, are skewered with everything from swordfish to cymbal stands to tennis rackets and small bicycles. In a trance, they walk in the middle of small entourages, shaking their heads from side to side, while their eyes roll back into their heads.

Both shirtless and shoeless, and wearing bright silk smocks emblazoned with fanciful dragons baring fangs and claws, the devotees claim to be possessed by a pantheon of spiritual entities—from Hindu gods like Shiva and the elephant-headed Ganesha to Chinese and Taoist divinities. It is these deities and a strict vegetarian diet, they say, which gives them the power to undergo the painful rites of penance, passage and purification through self-mutilation.

Many of the local onlookers, dressed in white as a symbol of purity, put their hands together to wai the participants—also known as ‘spirit warriors’—as they pass by, while other locals cluster behind makeshift shrines on the streets. Draped with red cloth, these wooden tables are set with bowls of burning joss sticks, plates of oranges, pineapples and candies, and nine tiny cups of tea—one for each of the Emperor Gods or Immortals of Taoism, who also represent the seven stars of the Big Dipper constellation and two others (from earth the formation resembles a yin-yang symbol). The deities are believed to attend the festival each year.

An elderly Thai woman standing among these streetside supplicants explained that their offerings and shows of respect for those possessed by the gods would bring them good luck.

But some of the tourists stared at the people in the procession like they were freaks. Raymond Jones, the aforementioned photographer with the tattoos and earrings, noted some similarities between the ‘modern primitive’ body-piercing trend and these ancient rites.

“They used to pierce their navels in ancient Egypt as a sign of nobility. And Roman centurions used to do it to show how virile they were. Some people may do it strictly for fashion’s sake today,” noted the young American computer programmer. “But my piercings and tattoos mark important turning points in my life. I got one when I graduated from high school, another when I got my first apartment, and then my tattoo of Isis [the Egyptian Goddess of Love] when I finished university.”

The coming-of-age rites that he spoke of also play a part in the Vegetarian Festival. Some of the devotees, both male and female, are still in their teens. Prasong, a 15-year-old fisherman, said, “It’s important for a man to show how strong he is, how much pain he can take.” By participating in the festivities, Prasong also believed that he could bring good fortune to himself and his community.

Some of the participants, however, are professional spirit mediums, or like Prasong’s father Veerawat, a mor phi (literally, ‘ghost doctor’). The 63-year-old—who had his face pierced by a steel bar draped with a garland of jasmine flowers for one of the processions—pointed to the Khmer script emblazoned on his back, and described in painful detail how a Buddhist monk at a temple in northern Thailand had stenciled it into his flesh while reciting magical incantations. As a latter-day shaman in Phuket, Veerawat consults various spirits for his clients, reads palms and dispenses herbal remedies. According to Veerawat, his magical tattoos have protected him against illnesses and accidents. “Look at me,” he said. “I’m still alive and I’ve never been seriously ill or in a car accident.”

In contrast, inked into his son’s skin was a tattoo of rock band Guns N’ Roses’ skull logo. In his left ear was a silver stud. “I am the new generation,” Prasong said with a grin.

The term ‘modern primitives’ was first coined by Roland Loomis in 1978 to define the neo-tribal movement of the tattooed, the pierced and the branded. Better known by his adopted name of Fakir Musafar, Loomis is a former advertising executive with a degree in electrical engineering and an MA in Creative Writing. He also founded the first school for body-piercing in the United States. A lecturer, shaman and legend in the fetish community, Loomis’ most famous and well-documented feat was performing the excruciating ‘Sun Dance’, a Native American spiritual rite that involves being hung from two big hooks piercing the chest and nipples. (The Ripley’s Believe It or Not Museum in Pattaya has a life-size tableau of a tribesman undergoing that rite of passage.) Much of the inspiration for his experiments with body modifications came from the indigenous peoples of the United States, and various Southeast Asian tribes and sects. For instance, the Hindu festival of Thaipusam, held outside Kuala Lumpur around February each year, attracts upwards of 100,000 people. The really devout have hooks put in their backs so they can drag chariots bedecked with flowers and Hindu idols up to the caves in a nearby mountain.

Many locals in Phuket are upset that the more extreme elements of the festival—walking on hot coals, scaling razor-runged ladders and spirit mediums licking hacksaw blades until their white smocks turn scarlet—have upstaged all the ascetic aspects, and that many travellers only come for the last three days of bloodletting and pyrotechnics. When I first attended the festival in 1997, people were already complaining that it had gotten out of control. A woman working at the Tourism Authority of Thailand’s office in Phuket said that the antics of the devotees had become increasingly outrageous over the years to impress the tourists and the gods. “Many foreigners who come to the festival only want to see the piercings and fireworks. They forget about the purity side of the festival—abstinence from alcohol, sex and eating meat. They don’t bother watching all the Chinese operas and dragon dances. I don’t like the piercings. They’re very, very boring,” said the woman, who asked not to be named.

To a certain extent, however, the shamans’ showmanship is in keeping with the festival’s first act. In 1825, a visiting Chinese opera troupe agreed to eat a strictly vegetarian diet and perform acts of self-mortification in the hope that the gods would stop the malaria epidemic that was decimating the local populace. After they performed these rites of atonement, the number of deaths mysteriously declined.

In Marlane Guelden’s informative and lavishly photographed book, Thailand Into The Spirit World, she linked the history of the performing arts in Southeast Asia with shamanism—many of the first performers were also traditional healers and practitioners of magic. The same is true in the West, where Greek tragedies evolved from magical ceremonies and the mythology of the country where the first Olympic Games were held to honour the gods.

Some of the expat community on the country’s largest island and second richest province find the festival’s lunatic fringe revolting. “Watching some of the men whipping themselves, or dancing with rows of safety pins stuck into each arm, that’s offputting to me,” said Alan Morison, the owner of local news website Phuketwan.com. After relocating to the island in 2002, the Australian has even seen “one or two people wrapped in barbed wire. It’s hard to dance when you’re wrapped up like that.” He laughed. “Authorities try to discourage the excesses but every year you still see a few people who have been pierced with the barrel of an AK-47 or have a BMX bicycle stuck through their cheeks with their friends carrying it as they walk.”

Wrenches, swordfish, cymbal stands and the odd AK-47 are all used during the world’s grisliest celebration of Taoist Lent, when ‘spirit warriors’ go into trances and become possessed by different deities.

Those ‘extreme elements’ also include more than a few members of the fetish scene, both Western and Asian. Mistress Jade, a Thai-Chinese dominatrix living and working on Phuket, said, “I think it’s the sexiest festival on earth. I always get some good ideas from it about what to do with subs in my play space,” before she burst out laughing. More seriously, she elaborated on the most piercing part of all the great faiths and status-quo systems of social control—guilt. “The rituals of penance that the warriors are doing are similar to some of my customers who feel guilty about having certain fantasies and fetishes. So they want me to make them suffer to absolve their guilt.”

In its penitential aspects—according to the ‘ghost doctor’, the warriors take on the pain and suffering of all their fellow humans—the Vegetarian Festival draws blood from the same vein as Easter in the Philippines. During Holy Week, surrogate ‘Christs’ are nailed to crosses on a volcanic Golgotha outside the town of San Fernando de Pampanga, where the streets are filled with hundreds of men, some dragging crosses, some wearing crowns of thorns and many flagellating themselves with cat-o’-nine-tails made from bamboo. In 1997, when I went for Holy Week for the first time, all foreigners were banned from being crucified because during the previous year, a Japanese man had been nailed to a cross. Only later did they find out he was an actor shooting the first scene in an S&M movie.

Taoist Lent in Phuket is nowhere near as gory or sorrowful as Easter in the Philippines. Many of the piercings are mundane. They demarcate certain professions. The man who installs satellite dishes has a TV antennae stuck through both cheeks. The gardener has a tree branch. The factory worker is skewered with a pineapple-laden shish kabob that has an ad for the local cement company where he works.

But some of the shamans are synonymous with shysters, who walk around with bars through their faces draped with Thai baht and pestering people to take photos of them to make a donation. By way of thanks they hand out a few ‘blessed candies’ (read: Hall’s lozenges).

In 2009, the authorities launched their biggest effort yet to crackdown on the frauds and extreme elements. Each of the 350 ‘spirit warriors’ was issued a special ID card with their full name and details, the name of the deity that possesses them, the temple to which they’re attached and a list of friends assisting them during the processions. That year also saw two more of the island’s Taoist temples join in the free-for-all (one on Rawai Beach, another in the Tungka district of Phuket city), bringing the total to 18 as occupancy rates soared to 70 per cent of the island’s 40,000 rooms—incredible for the soggy season. All the hotel rooms in Phuket city, where many of the rites are held at the elaborate Jui Tui Temple, were booked solid for months before the festival commenced with ceremonies on a deserted beach to welcome the gods ashore. For the traders in tourism, the windfall—according to TAT estimates—was 200 million baht.

As a high-voltage fixture on the travel circuit, it is surprising that the festival has not become more shockproof. But Alan noted, “The reason all the tourists keep coming is that it hasn’t been compromised. The believers still think that the gods come to visit, so for them it’s real. There’s no pretense about it. The Taoist communities in Singapore and Malaysia have their own versions, but without any of the incredible feats. So those nationals will come to Phuket. There probably was such a festival in China once, but it has now disappeared. So many of the visitors come from different parts of China.” The ladies in the TAT office said that the local version of Taoist Lent has never been celebrated like this in China; the piercing rites are spiked with Hindu influences from the Thaipusam Festival.

As popular as the Vegetarian Festival has become, there are still bastions of Chinese traditionalism and ‘demilitarised zones’ in the war-zone cacophony of exploding fireworks. Alan recommended the “old parts of Phuket city where there are some delightful parades and many of the older Chinese people come or sit outside their houses to watch”. Over the first few days of the festivities, the rituals of raising lanterns and praising the Emperor Gods are considerably more subdued, with not a drop of blood shed.

On a culinary level, Taoist Lent is celebrated all over Thailand. Just look for the restaurants and food carts flying yellow pennants. Many of the usual Thai dishes, liberally spiced with chilli, basil leaves and lemongrass, are on offer, as well as Chinese fare. The only difference is that the meat has been replaced by chunks of tofu that have been marinated so they look and taste like chicken, beef and seafood.

Some of the Taoist temples in the southern provinces of Phang-nga, Krabi and Trang celebrate the return of the Immortals, but only the capital of the latter province features any processions or feats of self-mortification.

On Phuket, the ‘spirit warriors’ who stick to a meat-free diet, wear white clothes and abstain from alcohol and sex, claim to be possessed on and off throughout the festival by the same entity.

“It’s quite surprising,” said Alan, “to see someone who works as a bank teller and suddenly they’re possessed and become this supernatural being for a short time. You do see people around with scarred cheeks, but it’s amazing how quickly they heal. It depends on the individual of course, but some of the warriors are back leading normal lives the next day with only a couple of bandages on their cheeks.”

For Western visitors, this is the most baffling part of Thailand’s extreme take on Taoist Lent. How can a person have both cheeks pierced with a sword and walk around for hours in the tropical heat and not wind up with hideous permanent scars? True believers claim that the gods who possess them, and the strict regimen of diet and asceticism, protect them. Most Westerners do not believe this.

Peter Davidson, the director of International Services at Phuket International Hospital, is one of the disbelievers. In an article for the Phuket Post in 2008, he wrote, “The cheeks predominantly consist of soft tissue; mostly skin, fat and some muscle which are used for facial expressions and eating. There are no large blood vessels in the cheek area, however, like all areas of the face and head, there is a complex blood vessel network with abundant small vessels. Because of this anatomy of the cheek, it is unlikely that significant bleeding is present when the cheek is pierced. With piercing, a puncture wound is made, which typically bleeds less than a laceration or other type of wound. This, coupled with the anatomy of the cheek, could explain why bleeding is minimal. Over recent years it has been a requirement that a doctor be available at the temples where mah song are pierced, and it is not unusual for these doctors to have to perform some suturing and wound repair where the puncture or piercing practice elicits too much bleeding.”

In his opinion, the fact that most of the participants are young men means that their wounds heal faster. Medical precautions have also diminished the high-risk stakes. All the men and women taking part are now required to have HIV checks before they get pierced, and the paramedics on hand at all the temples where the piercing is done wear gloves and sterilise the objects to be inserted. The main risk is that the wounds will get infected.

Some of the

feats the mah song perform are not as easy to explain. At night, the

‘entertainment’ includes demonstrations of walking through beds of glowing red

coals—that are a good ten-metres

long and 20-metres wide—in front of Chinese temples ablaze with shades of gold

and scarlet, while some warriors scale ten-metre-high ladders runged with

razorblades sharp enough to shave with. In 2009, one of the fire-walkers at the

temple of Tharua fell face first onto the coals. In a flash, flames engulfed

his white trousers and the traditional apron. Several spectators ran to his

rescue. They dragged him to safety but not nearly quick enough to prevent

serious burns that kept him in the hospital for weeks of treatments, followed

by months of physiotherapy so he could learn how to walk again.

“That man clearly did not have the spirits inside him,” said Alan Morison. “It should satisfy the skeptics that these ‘warriors’ are doing some incredible things.”

Of all the spirit mediums Alan has met or interviewed, one man stands out. “He’s a Buddhist but becomes possessed by the spirit of a Muslim religious leader who was highly respected in that area. He has Taoist and Muslim shrines in his house. A Thai woman I know regularly consults him as a kind of oracle, often for big decisions she wants to make, such as the best time to buy a new car. She’s not an ignorant or superstitious woman. Nor are the other people who go to see him. They respect his wisdom. It’s really quite strange to see this man who only speaks Thai go into trances where he speaks Arabic and recites lines from the Koran.”

Allan was right about that. Watching the devotees go into trances before they are pierced is strange. At first, they start twitching and shaking their heads, then they approach the metal altar in the temple, banging on it with their fists and making high-pitched noises. As they begin to shake more violently, one or more of their minders sneaks up from behind to tie on a special smock emblazoned with Chinese dragons and yin-yang symbols. But the devotees’ Thai name mah song (‘entranced horses’) is telling—the gods are said to ride them like horses. That is not unique to Thailand. The dancers in the white magic rites of Haitian vodou—as opposed to the black magic of Hollywood voodoo—were captured undergoing similar transformations by filmmaker and ethnographer Maya Derin in her riveting book and documentary, Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti.

Many Thai ceremonies revolve around men and women being possessed, like the underground gatherings of spirit mediums and the now infamous Tattoo Festival at Wat Bang Phra, near the town of Nakhon Chaisri. There, a motley crew of gangsters and blue-collar workers are taken over by the animal deities inked on their skin—roaring like tigers, hopping around like monkeys and snaking across the dirt on their bellies.

In Phuket, some of the wildest spectacles take place on the last night of the festival during the ‘Farewell to the Gods’ ceremony, when the backstreets of the island’s capital are cloaked in darkness and illuminated only by a few streetlamps, the golden glow of candles on makeshift shrines and firecrackers exploding everywhere. (Bring earplugs and flame-retardant headgear is the best travel advice.) Overhead, the sky was an aurora borealis of pyrotechnics, the smithereens fading as they fizzle out and fall. At the same time, the warriors—unpierced and carrying black flags emblazoned with sacred incantations that are supposed to protect them, and cracking whips to drive away malevolent spirits—strode through the streets with their entourages. Behind them came men carrying sedan chairs that housed icons of the Taoist divinities so they could be released back into the sea, as standard-bearers hoisted golden dragons on poles.

Watching Veerawat, the middle-aged ‘ghost doctor’, dancing under a streetlamp while teenagers threw lit firecrackers at his bare feet, was mesmerising. Balancing on one foot like a Thai classical dancer while holding the black flag aloft, he slowly and gracefully arced in a circle. An older Chinese man lowered a string of firecrackers on a pole just above the warrior’s head. A single spark set off a chain reaction of big bangs. One after another, the firecrackers exploded in his face. He did not flinch or even blink; and kept spinning around in a circle like a whirling dervish. This was one of the most incredible acts of endurance and grace under pressure that I’ve ever witnessed. Whether he was actually possessed by a higher power, or whether it was his faith that gave him the power to withstand such a deafening bombardment, it did not really matter. Either way, it was an athletic and artistic feat of Olympian proportions. With that kind of willpower and indifference to pain, what other achievements arepossible?

On this night, Veerawat’s entourage consisted of Ray the computer programmer and two Chicago punk rock girls who were tattooed and pierced from ankles to eyebrows. Ray, who has tattoos of Isis, Osiris and John Lennon to mark turning points in his life and a Prince Albert piercing in his nether regions, said, “Kelly and I went to this ‘Spirit and Flesh’ workshop run by Fakir Musafar, where you go through ecstatic states of shamanism through rituals of body modification and piercing. We had all sorts of trippy visions and revelations. But it was more like, rising above the pain and purifying yourself, finding something bigger and better—kind of like this festival.”

Fakir Musafar, the man who coined the term ‘modern primitives’ and who, at the age of 79, still runs his own body-piercing studio, explained during one of his lectures, “Intense physical sensations create focus which gives one the ability to do things in life that you couldn’t do with unfocused attention.”

Ask any virtuosic musician or martial arts expert and they’ll tell you much the same thing.

Unhurt and unfazed by all the pyrotechnics, the modern-day shaman strode down the street like a warrior going into battle. His entourage of three young punks—who were on a spiritual and psychological mission to transcend suffering and rise above middle-class mediocrity through this ancient and arcane wisdom—scurried to catch up with a Thai man old enough to be their grandfather.

In a way, that’s exactly who he was.