The ghost of a woman who dies in childbirth—a phi tai hong thong klom—is regarded as the most fearsome of all phantoms in Thailand. In a scene from Nang Nak—the famous Thai horror movie based on the country’s most enduring ghost story—a terrified widower and a group of Buddhist monks are sitting on the floor of a temple chanting mantras to protect themselves when drops of water begin falling on them. They all look up to see the man’s dead wife standing upside down on the ceiling of the temple, glowering at them while dripping sweat.

At the ‘Temple of Mother Nak’ off Sukhumvit Road, where many believe her spirit still resides, a Thai man pointed out to me a strange indentation on the ceiling of the main shrine, declaring that this was the place where Nak once stood.

Long before the Siamese even had surnames, the real Nak was supposedly born here in the middle of the 19th century. The village of Phra Khanong, once a patchwork of rice paddies crisscrossed with canals—some of which have still not been paved over—later became a district of the capital. As the legend and the 1999 film go, her husband Mak went off to fight the Burmese, leaving his pregnant wife behind. When they were reunited, Nak showed him their newly born son. But Mak could not understand why she was so aloof and kept rejecting his overtures to make love.

A few scenes later, when the couple are making love on the floor, the scene is edited together with a flashback of Nak dying while giving birth in the old Siamese way—sitting on the floor, her arms tied above her head, as beads of blood drip through the floorboards onto the head of a water buffalo tethered below the house. Never mind the supernatural sex that left audiences around the world gasping and murmuring—“He’s sleeping with a ghost and doesn’t even know it!”—the scene was remarkable for the way it contained an entire revolution on the Buddhist Wheel of the Law: birth, death and rebirth.

Such deaths were common in Nak’s day. In the film and the rural legend, Nak went on a killing spree to keep the other villagers from exposing her secret to her husband.

After watching her frightful and tender performance on-screen it was a shock to see that, in real life, the cinematic reincarnation of the country’s most famous ghost was a teenaged college girl with spiky tendrils of frosted blonde hair. Only 19 at the time, Inthira ‘Sai’ Chareonepura radiated none of the menace she showed on-screen. Sitting in her school uniform of a black skirt and white blouse, beaming with smiles and politely answering questions, she could have been one of a million university students in the country.

Sai noted that Nak’s story has been made into more than 20 different films, but the 1999 version was different because it focused more on the couple’s relationship.

“The previous versions of Nang Nak are more about scary things and horror—not the love story. But the director [Nonzee Nimibutr] wanted to make this a love story about Nak’s faithfulness to her husband as she waits for him [to return from the war]. Even after she dies, she’s still worried about him and comes back to take care of him.”

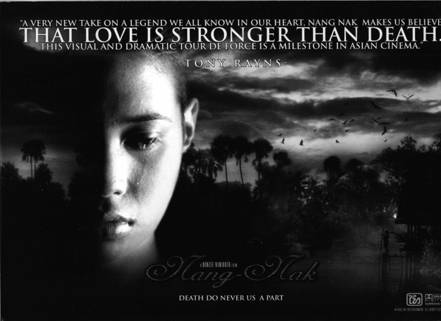

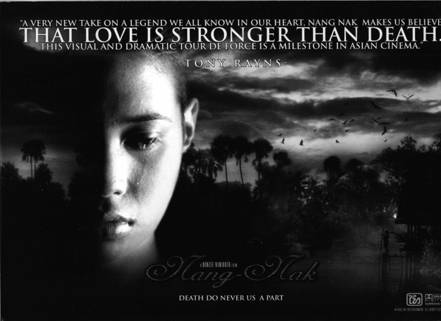

The movie poster for Nonzee

Nimibutr’s version of Nang Nak. Produced by Tai Entertainment, and starring Sai

Charoenpura, the film brought Thai cinema back from the dead by conjuring up

the

country’s most legendary phantom.

That’s true. What made this version a cut above the usual slasher-and-horror fare is the full-bodied romance. The climax is especially heartrending when the couple is caught in the middle of a rainstorm while the Buddhist monk who moonlights as a ghost-hunter attempts to trap Nak’s spirit forever.

Even the most oblique and subtle questions about the infamous sex scene turned Sai into a giggling and blushing schoolgirl. “Yes, giving birth in the old way... that wasn’t me. They had a body double,” she said, before breaking into a fit of laughter.

Since this was the most controversial part of the entire film, it certainly required an explanation. Further questions were answered by more giggles and denials. Tiring of this typically Thai coquettish routine, I asked her point-blank, “So was that really you rolling around on the floor of the house?”

You would’ve thought this was the funniest joke she had ever heard. Composing herself after another fit of hysterics, Sai managed to say, “Yes, that was me,” before explaining that many previous productions of the film were plagued with problems thought to have occult causes. That’s why cinemas once set up shrines to appease her spirit. One old movie house that did not follow this ritual was razed to the ground by a freak fire. As was, and still is the tradition, the whole cast and crew paid homage to her restless spirit before they shot the film, at the shrine behind the temple off Sukhumvit Soi 77 (officially known as Wat Mahabut).

The glass case in front of the statue of Nak holding her baby boy is laden with offerings such as cosmetics and jewellery. Off to the left is another cabinet full of toys and baby clothes for Nak’s son. Hundreds of people (both male and female) come here every day to pray to her for wealth, love and other favours. As at any Buddhist altar, they light candles and incense before they kneel and bow, and stick gold leaves on the statue. Some of them also slip money into the hands of the icon. Outside the shrine, a number of people pour candle wax on a sacred takian (malabar) tree in an attempt to discern winning lottery numbers.

The older Thai man who gave me a tour of the temple (and who thought the movie was perfectly accurate) picked up a leaf from the sacred bodhi tree near the altar and handed it to me, saying it would bring me good luck.

Outside the shrine are dozens of little stalls in the business of divination: palm-readers, fortune tellers and tarot card experts. As a centre of spiritual power, blessed by Nak’s presence, these oracles are legendary. Their customers are a cross-section of Thai society from every rung of the corporate and blue-collar ladder. Gay, a young businesswoman who had lived and studied in England for years, said, “I believe about 50 per cent of what they tell me. Sometimes they can be quite accurate. One fortune-teller told me I would get robbed in the next six months so I should be careful. A month or two later, I had my purse stolen by a guy riding by on a motorcycle.”

Usually, she prefers consulting monks. The Buddha forbade such prophecies, but Thais follow the tradition of his student Mogellana. After the ‘Awakened One’ passed away, Mogellana put the teachings of his mentor and the mental power he had acquired from meditation to the task of divining the future.

“With the monks, I like to talk to a senior person with wisdom and experience whom I can trust. Thais don’t like talking about their problems very much, and going to see psychiatrists is too much of a loss of face. So the monks and fortune-tellers serve many roles as consultants, psychiatrists and community leaders.”

Many Westerners and Thais scorn these fortune-tellers and spirit-worshippers as superstitious throwbacks to the past. But the supernatural haunts so many different facets of Thai life, love and festivities, that exorcising those beliefs from the collective consciousness would purge the culture of its vitality and its history. Ghouls throng the streets of Dansai in Loei province during the Phi Ta Khon (Ghosts with Human Eyes) Festival, usually held in June, depending on what the local soothsayer deems an auspicious day. In weaving a hedonistic yarn around an ancient folktale about Prince Vessandara (the Buddha in his last reincarnation) returning to his hometown for a festival so jubilant that even the spirits could not help but join in, the Thai spin has young men wearing shamanistic masks and waving wooden phalluses as they cavort around the town impersonating spirits. Old men dressed as women offer shots of moonshine to all and sundry, while processions of beauty queens and traditional dancers wend their way through the crowds. It’s about as surreal as religious festivals get; condensing a thousand years of Thai history into a few short and exhilarating days.

Until Nang Nak brought about a rebirth of Thai cinema, the local movie industry had languished in critical condition—filmmakers couldn’t decide whether to emulate Hong Kong or Hollywood. But Nonzee Nimibutr’s reliance on local folkloric colour—the entire cast and crew had to take a four-month course in Siamese history—proved that Thai exotica could enchant foreign audiences and inspire local moviemakers. Even the most horrific scene in the film, when monitor lizards savage the corpse of a villager Nak killed, has Thai teeth marks all over it. Without the influence of this ghost story, it’s doubtful that local cinema would have enjoyed the global success it has in recent years and notched up the first Cannes Award for a Thai movie.

The spirits from a Buddhist folktale are reborn during the festival of Phi Ta Khon (Ghosts With Human Eyes).

Foreign women inspire ghoulish affections at this festival in Loei province.

Some authors, like Tiziano Terzani in A Fortune-Teller Told Me, have speculated that these seers possess an ‘ability’ that has waned through the imagination-destroying influence of technology and consumerism, but still survived in remnants of Asia.

It’s a point worth pondering. In the early months of 2003, Anchana had to wake up early to finish her last semester of university. Every morning, in the distance, she would see an old woman dressed in a traditional sarong sweeping the parking lot in front of our ground-floor apartment. When she asked the landlady who the woman was, Jazz asked her for a description. The landlady nodded. “That poor old lady was hit and killed by a motorcycle just outside our front gate a few weeks ago. I guess she doesn’t realise she’s dead yet, so she keeps on doing her duty.”

This did not strike them as strange. In their belief system, these things happen all the time. As long as the old woman did not hurt anyone, they would practice the Thai-Buddhist doctrine of ‘live and let live, mai pen rai (never mind)’. At some point, all of the Thai neighbours saw the ‘ghost’. In spite of repeated reconnaissance missions, I never caught so much as a fleeting glimpse of her shadow. But I was trying to see her and they were not. I was out there as a spectator and a writer, a skeptic and debunker, and as someone from a Judeo-Christian background.

Does faith open doors that skepticism closes? Are Thais peering into a different realm by activating the ‘third eye’ of Indian lore?

The mystery of Thailand’s most famous ghost story opens a pandora’s box of far darker and much more ancient questions. First and foremost is: why are so many people worshipping a woman who, besides being a faithful wife and a good mother, was a multiple murderess?

Some of the answers to these questions may lie in the Hindu faith and Chinese beliefs, which inform much of Thai mysticism and culture. Hindu deities such as Shiva and his wife Parvati have vastly different incarnations that are at odds with each other. In Parvati’s other guise as Kali—or Kalika, the goddess of death and time—her dress is fashioned from a tiger skin, her belt strung with severed heads, and her multiple arms clutch weapons such as a noose and sword.

Hindu legend has it that two demon overlords and their minions had ravaged the planet before launching an assault on the heavens, when Parvati, bathing in the Ganges River, heard the gods beseeching her for help. So she used her own body to create Kali, who in turn gave birth from a hole in her forehead, to a more savage incarnation known as the ‘Dark Mother’. Engaging the demons in battle, she used her sword to maim and lacerate them, but every drop of blood that hit the ground spawned another fiend. Kali lashed out with her whip-length tongue to lick up the blood before it hit the ground. She then conjured up two assistants, giving them nooses to strangle the demons before their blood could spawn a new army.

To this day, Kali’s bloodlust is appeased by animal sacrifices at the temple devoted to her in Kolkatta (a city named after the Dark Mother), India, particularly during the October festival held to pay homage to her. Hindu temples in Bangkok bear images of Kali and her incarnations, and the tributes to Pavarti are celebrated amidst much revelry each year.

Thais take their Indian idols very seriously. When a mentally ill man destroyed the beloved statue of Brahma at the Erawan Shrine in 2006, he was beaten to death by a couple of men who had witnessed the destruction. A monk who wrote in the Bangkok Post said that the dead man had received his karmic payback. His article drew a flurry of furious letters from foreign readers. The mystically inclined, however, saw the statue’s destruction as a portent of disaster—they felt their beliefs had been vindicated when the government was ousted only a month later.

Guan Yin, the Taoist Goddess of Mercy, is also widely worshipped in Thailand. Illustrations of her, robed in white and standing on the nose of a dragon, are common currency for those who bank on the spirit world. Women pray at shrines devoted to Guan Yin in Thailand, leaving pearl necklaces in the hope she will make them pregnant. Stories of Guan Yin’s powers of fertility are legendary. One Chinese fable states that the goddess fertilised rice paddies with her breast milk. But in other legends and statues she is a male Buddhist saint named Avalokitsvara (a Sanskrit word), who appears in different forms in Tibet, Burma and Indonesia.

Like Kali and Guan Yin, Nak is a figure shrouded in dualism. By turns loving and maternal, sinister and sexy, Nak’s complex nature has made her attractive to a host of different filmmakers. In 2005, The Ghost of Mae Nak, the first movie version written and directed by a foreigner—Mark Duffield from England—was released to mixed reviews. According to Tom Waller, the producer of the film, they modernised the tale but remained faithful to its spirit. “The young couples’ love awakens the spirit of Mother Nak, and it’s told through the grandmother’s eyes, so we can do some flashbacks to explain the legend. But mostly the film is set in contemporary Bangkok. We shot it at some creepy locations around Sukhumvit Soi 77 like the canal and the old market. Some of the Thai crew got a bit freaked out and would joke that Mae Nak was just around the corner.”

Another strand of the story that continues to fascinate is the many different accounts of what happened to Nak’s spirit. Was it ever laid to rest? Theories are rife, but evidence is scant. Tom, however, sides with folklorists who believe that after the monk took a bone out of the dead woman’s forehead to contain her spirit, he wore it around his neck like an amulet.

“We’ve dramatised all this in the film, but nobody knows what happened to this ‘bone broach’ after the monk died. It just disappeared,” Tom said. “We’re hoping someone who sees the film will be able to tell us what happened to it.”

Since then, there have not been any more films or TV series about Nak. Given the new breed of Asian horror with spectres crawling out of TV sets, using mobile phones, infesting penthouses and wreaking havoc in a phantasmagoria of special effects, the story of a rural woman from a 19th century farming community doesn’t have a ghost of a chance at the box office these days.

That, however, has not stopped all the supplicants from coming to her shrine. Some are mystical mercenaries asking for wealth and looking for winning lottery numbers in the etchings on the trees outside the shrine, but many pray to her for love or seek to cure their maladies of the heart. As Gay said about locals consulting monks and fortune-tellers as psychiatrists, Nak is also something of a relationship counsellor. Before her shrine, the lovelorn can vent their bleeding hearts without losing ‘face’ in front of anyone.

In his non-fiction book Heart Talk, Christopher Moore reckons that Thais have more expressions about this muscle than any other culture. The outpouring of songs, films, soap operas and TV shows devoted to the ins and outs of love is a never-ending flood. In that genre of romantic tragedies, the tale of a woman who died in childbirth while her husband was on the battlefield and came back from the dead along with their child to take care of him, comes from a real and much more haunting place than any of these other make-believe stories about rampaging ghouls.

As every widower and lonely heart knows, all love sagas become ghost stories in the end.