When he next looked at the sky a half-moon was sailing over it. He said, “Rima, I think we should try to keep moving.” She got to her feet and they started walking arm in arm. She said miserably, “It was wrong of you to be glad.”

“There’s nothing to worry about, Rima. Listen, when Nan was pregnant she had nobody to help her, but she still wanted a baby and had one without any bother.”

“Stop comparing me with other women. Nan’s a fool. Anyway, she loved Sludden. That makes a difference.”

Lanark stood still, stunned, and said, “Don’t you love me?” She said impatiently, “I like you, Lanark, and of course I depend on you, but you aren’t very inspiring, are you?”

He stared at the air, pressing a clenched fist to his chest and feeling utterly weak and hollow. An excited expression came on her face. She pointed past him and whispered, “Look!”

Fifty yards ahead a tanker stood on the verge with a man beside it, apparently pissing on the grass between the wheels. Rima said, “Ask him for a lift.”

Lanark felt too feeble to move. He said, “I don’t like begging favours from strangers.”

“Don’t you? Then I will.”

She hurried past him, shouting, “Excuse me a minute!”

The driver turned and faced them, buttoning his fly. He wore jeans and a leather jacket. He was a young man with spiky red hair who regarded them blankly. Rima said, “Excuse me, could you give me a lift? I’m terribly tired.”

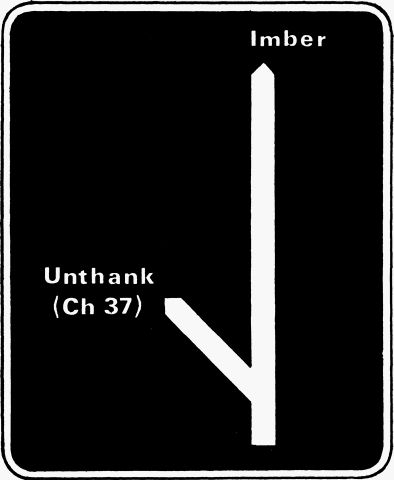

Lanark said, “We’re trying to get to Unthank.”

The driver said, “I’m going to Imber.”

He was staring at Rima. Her hood had fallen back and the pale golden hair hung to her shoulders, partly curtaining her ardently smiling face. The coat hung open and the bulging stomach raised the short dress far above her knees. The driver said, “Imber isn’t all that far from Unthank, though.”

Rima said, “Then you’ll let us come?”

“Sure, if you like.”

He walked to the cab, opened the door, climbed in and reached down his hand. Lanark muttered, “I’ll help you up,” but she took the driver’s hand, set her foot on the hub of the front wheel and was pulled inside before Lanark could touch her. So he scrambled in after and shut the door behind him. The cabin was hot, oil-smelling, dimly lit and divided in two by a throbbing engine as thick as the body of a horse. A tartan rug lay over this and the driver sat on the far side. Lanark said, “I’ll sit in the middle, Rima.”

She settled astride the rug saying, “No, I’m supposed to sit here.”

“But won’t the vibration … do something?”

She laughed.

“I’m sure it will do nothing nasty. It’s a nice vibration.”

The driver said, “I always sit the birds on the engine. It warms them up.”

He put two cigarettes in his mouth, lit them and gave one to Rima. Lanark settled gloomily into the other seat. The driver said, “Are you happy then?”

Rima said “Oh, yes. It’s very kind of you.”

The driver turned out the light and drove on.

The noise of the engine made it hard to talk without shouting. Lanark heard the driver yell, “In the pudding club, eh?”

“You’re very observant.”

“Queer how some birds can carry a stomach like that without getting less sexy. Why you going to Unthank?”

“My boyfriend wants to work there.”

“What does he do?”

“He’s a painter—an artist.”

Lanark yelled, “I’m not a painter!”

“An artist, eh? Does he paint nudes?”

“I’m not an artist!”

Rima laughed and said, “Oh, yes. He’s very keen on nudes.” “I bet I know who his favourite model is.”

Lanark stared glumly out of the window. Rima’s hysterical despair had changed to a gaiety he found even more disturbing because he couldn’t understand it. On the other hand, it was good to feel that each moment saw them nearer Unthank. The speed of the lorry had changed his view of the moon; its thin crescent stood just above the horizon, apparently motionless, and gave a comforting sense that time was passing more slowly. He heard the driver say, “Go on, give it to him,” and Rima pushed something plump into his hands. The driver shouted, “Count what’s in it—go on count what’s in it!”

The object was a wallet. Lanark thrust it violently back across Rima’s thighs. The driver took it with one hand and yelled, “Two hundred quid. Four days’ work. The overtime’s chronic but the creature pays well for it. Half of it yours for a drawing of your girl here in the buff, right?”

“I’m not an artist and we’re going to Unthank.”

“No. Nothing much in Unthank. Imber’s the place. Bright lights, strip clubs, Swedish massage, plenty of overtime for artists in Imber. Something for everybody. I’ll show you round.”

“I’m not an artist!”

“Have another fag, ducks, and light one for me.”

Rima took the cigarette packet, crying, “Can you really afford it?”

“You saw the wallet. I can afford anything, right?”

“I wish my boyfriend were more like you!”

“Thing about me, if I want a thing, I don’t care how much I pay. To heck with consequences. You only live once, right? You come to Imber.”

Rima laughed and shouted, “I’m a bit like that too.”

Lanark shouted, “We’re going to Unthank!” but the others didn’t seem to hear. He bit his knuckles and looked out again. They were deep among lanes of vast speeding vehicles and container trucks stencilled with cryptic names: QUANTUM, VOLSTAT, CORTEXIN, ALGOLAGNICS. The driver seemed keen to show his skill in overtaking them. Lanark wondered how soon they would reach the road leading off to Unthank, and how he could make the lorry stop there. Moreover, if the lorry did stop, he (being near the door) must get out before Rima. What if the driver drove off with her? Perhaps she would like that. She seemed perfectly happy. Lanark wondered if pregnancy and exhaustion had driven her mad. He felt exhausted himself. His last clear thought before falling asleep was that whatever happened he must not fall asleep.

He woke to a perplexing stillness and took a while understanding where he was. They were parked at the roadside and an argument was happening in the cabin to his right. The driver was saying angrily, “In that case you can clear out.” Rima said, “But why?”

“You changed your mind pretty sudden, didn’t you?”

“Changed my mind about what?”

“Get out! I know a bitch when I see one.”

Lanark quickly opened the door saying, “Yes, we’ll leave now. Thanks for the lift.”

“Take care of yourself, mate. You’ll land in trouble if you stick with her.”

Lanark climbed on the verge and helped Rima down after him. The door slammed and the tanker rumbled forward, becoming a light among other lights whizzing into the distance. Rima giggled and said, “What a funny man. He seemed really upset.”

“No wonder.”

“What do you mean?”

“You were flirting with him and he took it seriously.”

“I wasn’t flirting. I was being polite. He was a terrible driver.” “How does the baby feel?”

Rima flushed and said, “You’ll never let me forget that, will you?”

She started rapidly walking.

The road ran between broad shallow embankments. Rima said suddenly, “Lanark, have you noticed something different about the traffic? There’s none going the opposite way.” “Was there before?”

“Of course. It only stopped a minute ago. And what’s that noise?”

They listened. Lanark said, “Thunder, I think. Or an aeroplane.”

“No, it’s a crowd cheering.”

“If we walk on we may find out.”

It became plain that something strange was happening ahead, for lights had begun clustering on the horizon. The embankment grew steeper until the road passed into a cutting. The verge was now a grassy strip below a dark black cliff with thick ivy on it. Wailing sirens sounded behind them and police cars sped past toward the light and thunder. The cutting ahead seemed blocked by glare, and vehicles slowed down as they neared it. Soon Rima and Lanark reached a great queue of trucks and tankers. The drivers stood on the verge talking in shouts and gestures, for the din increased with every step. They passed another road sign:

: and eventually Rima

halted, pressed her hands over her ears, and by mouthings and headshakings made it clear she would go no farther. Lanark frowned angrily but the noise made thought impossible. There was something animal and even human in it, but only machinery could have sustained such a huge screeching, shrieking, yowling, growling, grinding, whining, yammering, stammering, trilling, chirping and yacacawing. It passed into the earth and jarred painfully on the soles of the feet. Still holding her ears Rima turned and hurried back and Lanark, after a moment of hesitation, was glad to follow.

Many more vehicles had joined the queue and drivers were standing on the road between them, for the backs of the trucks gave shelter from the sound. A young policeman with a torch was speaking to a group and Lanark gripped Rima’s sleeve and drew her over to listen. He was saying, “A tanker hit an Algolagnics transporter at the Unthank intersection. I’ve never seen anything like it—nerve circuits spread across all the lanes like bloody burst footballs and screaming enough to crumble the road surface. The council’s been alerted but God knows how long they’ll take to deal with a mess like that. Days—weeks, perhaps. If you’re going to Imber you’ll need to go round by New Cumbernauld. If you’re for Unthank, well, forget it.”

Someone asked him about the drivers.

“How should I know? If they’re lucky they were killed on impact. Without protective clothes you can’t get within sixty metres of the place.”

The policeman left the group and Lanark touched his shoulder saying, “Can I speak to you?”

He flashed his torch on their faces and said sharply, “What’s that on your brows?”

“A thumb print.”

“Well, how can I help you, sir? Be quick, we’re busy at the moment.”

“This lady and I are travelling to Unthank—”

“Out of the question sir. The road’s impassable.”

“But we’re walking. We needn’t keep to the road.”

“Walking!”

The policeman rubbed his chin. At length he said, “There’s the old pedestrian subway. It hasn’t been used for years, but as far as I know it isn’t officially derelict. I mean, it isn’t boarded up.”

He led them across the grass to a dark shape on the cutting wall. It was a square entrance, eight feet high and half hidden by a heavy swag of ivy. The policeman flashed his torch into it. A floor, under a drift of withered leaves, sloped down into blackness. Rima said firmly, “I’m not going in there.”

Lanark said, “Do you know how long it is?”

“Can’t say, sir. Wait a minute….”

The policeman probed the wall near the entrance with his torch beam and revealed a faded inscription:

EDESTRIAN UNDER ASS UNTHAN 00 ETRES

The policeman said, “A subway with an entrance like this can’t be very long. A pity the lights are broken.”

“Could you possibly lend me your torch? We mislaid ours and Rima—this lady—is pregnant, as you see.”

“I’m sorry sir. No.”

Rima said, “It’s no use discussing it. I refuse to go in there.” The policeman said, “Then you’ll have to hitch a lift back to New Cumbernauld.”

He turned and walked away. Lanark said patiently, “Now listen, we must be sensible. If we use this tunnel we’ll reach Unthank in fifteen minutes, perhaps less. It’s unlit but there’s a handrail on the wall so we can’t lose our way. New Cumbernauld may be hours from here, and I want to get you into hospital as quickly as possible.”

“I hate the dark, I hate hospitals and I’m not going!”

“There’s nothing wrong with darkness. I’ve met several dreadful things in my life, and every one was in sunshine or a well-lit room.”

“Yet you pretend to want sunshine!”

“I do, but not because I’m afraid of the opposite.”

“How wise you are. How strong. How noble. How useless.” Bickering fiercely they had moved into the tunnel mouth to escape the blast of the din outside. Lanark abruptly paused, pointed into the dark and whispered, “Look, the end!”

Their eyes had grown used to the black and now they could see, in the greatest depth of it, a tiny, pale, glimmering square. Rima suddenly gripped the handrail and walked down the slope. He hurried after her and silently took her arm, afraid a wrong word would overturn her courage.

The roaring behind them sank into silence and the withered leaves stopped whispering under their feet. The ground levelled out. The air grew cold, then freezing. Lanark had kept his eyes fixed on the glimmering little square. He said, “Rima, have you let go the handrail?”

“Of course not.”

“That’s funny. When we entered the tunnel the light was straight ahead. Now it’s on our left.”

They halted. He said, “I think we’re moving along the side of an open space, a hall of some kind.”

She whispered, “What should we do?”

“Walk straight toward the light. Can’t you button your coat?”

“No.”

“We must get out of this cold as fast as we can. Come on. We’ll go straight across the middle.”

“What if … what if there’s a pit?”

“People don’t build pedestrian subways with pits in the middle. Let go of the rail.”

They faced the light and stepped cautiously out, then Lanark felt himself slipping downward and released Rima’s arm with a yell. Head and shoulder met a dense, metal-like surface with such stunning force that he lay on it for several seconds. The hurts of the fall were far less than the intense freezing cold.

The chill on his hands and face actually had him weeping.

“Rima,” he moaned, “Rima, I’m sorry … I’m sorry. Where are you, please?”

“Here.”

He crawled in a circle, patting at the ground until his hand touched a foot. “Rima … ?”

“Yes.”

“You’re wearing thin sandals and you’re standing on ice. I’m sorry, Rima, I’ve led you onto a frozen lake.”

“I don’t care.”

He stood up, his teeth chattering, and peered about, saying, “Where’s the light?”

“I don’t know.”

“I can’t see it … I can’t see it anywhere. We must find our way back to the handrail.”

“You won’t manage it. We’re lost.” Her body was beside him but her voice, low and dull, seemed to come from a distance. She said, “I’m a witch. I deserve this for killing him.”

Lanark thought she had gone mad and felt terribly weary. He said patiently, “What are you talking about, Rima?”

After a moment she said, “Pregnant, silent, freezing, all dark, lost with you, feet that might fall off, an aching back, I deserve all this. He was driving badly to impress me. He wanted me, you see, and at first I found that fun; then I got tired of him, he was so smug and sure of himself. When he made us get out I wanted him to die, so he went on driving badly and crashed. No wonder you mean to lock me in a hospital. I’m a witch.”

He realized she was weeping desperately and tried to embrace her, saying, “In the first place, the tanker that crashed may not be the one that gave us the lift. In the second place, a man’s bad driving is nobody’s fault but his own. And I’m not going to lock you up anywhere.”

“Don’t touch me.”

“But I love you.”

“Then promise not to leave when the baby comes. Promise you won’t give me to other people and then run away.”

“I promise. Don’t worry.”

“You’re only saying that because we’re freezing to death. If we get away from here you’ll hand me over to a gang of bloody nurses.”

“I won’t! I won’t!”

“You say that now, but you’ll run away when the real pains begin. You won’t be able to stand them.”

“Why shouldn’t I stand them? They’ll be your pains, not mine.” She gasped and shrieked, “You’re glad! You’re glad! You evil beast, you’re glad!”

He shouted, “Everything I say makes you think I’m evil!”

“You are evil! You can’t make me happy. You must be evil!” Lanark stood gasping dumbly. Every comforting phrase which struck him was accompanied by a knowledge of how she would twist it into a hurt. He raised a hand to hit her but she was with child; he turned to run away, but she needed him; he dropped down on his hands and knees and bellowed out a snarling yell which became a howl and then a roar. He heard her say in a cold little voice, “You won’t frighten me that way.”

He yelled out again and heard a distant voice shout, “Coming! Coming!”

He stood up, drawing breath with effort and feeling the chill of the ice on his hands and knees. A light was moving toward them over the ice and a voice could be heard saying, “Sorry I’m late.”

As the light neared they saw it was carried by a dark figure with a strip of whiteness dividing head from shoulders. At last a clergyman stood before them. He may have been middle-aged but had an eager, smooth, young-looking face. He held up the lamp and seemed to peer less at Lanark’s face than at the mark on his brow. There was a similar mark on his own. He said, “Lanark, is it? Excellent. I’m Ritchie-Smollet.”

They shook hands. The clergyman looked down on Rima, who had sunk down on her heels with her arms resting wearily on her stomach. He said, “So this is your good lady.”

“Lady,” snarled Rima contemptuously.

Lanark said, “She’s tired and a bit unwell. In fact she’ll be having a baby quite soon.”

The clergyman smiled enthusiastically.

“Splendid. That’s really glorious. We must get her into hospital.”

Rima said violently, “No!”

“She doesn’t want to go into hospital,” explained Lanark.

“You must persuade her.”

“But I think she ought to do what she likes.”

The clergyman moved his feet and said, “It’s rather chilly here. Isn’t it time we put our noses above ground?”

Lanark helped Rima to her feet and they followed Ritchie-Smollet across the black ice.

It was hard to see anything of the cavern except that the ceiling was a foot or two above their heads. Ritchie-Smollet said, “What tremendous energy these Victorian chaps had. They hollowed this place out as a burial vault when the ground upstairs was filled up. A later age put it to a more pedestrian use, and it still is a remarkably handy short cut…. Please ask any questions you like.”

“Who are you?”

“A Christian. Or I try to be. I suppose you’d like to know my precise church, but I don’t think the sect is all that important, do you? Christ, Buddha, Amon-Ra and Confucius had a great deal in common. Actually I’m a Presbyterian but I work with believers of every continent and colour.”

Lanark felt too tired to speak. They had left the ice and were climbing a flagged passage under an arching roof. Ritchie-Smollet said, “Mind you, I’m opposed to human sacrifice: unless it’s voluntary, as in the case of Christ. Did you have a nice journey?”

“No.”

“Never mind. You’re still sound in wind and limb and you can be sure of a hearty welcome. You’ll be offered a seat on the committee, of course. Sludden was definite about that and so was I. My experience of institute and council affairs is rather out of date—things were less tense in my time. We were delighted when we heard you had chosen to join us.”

“I’ve chosen to join nobody. I know nothing about committee work and Sludden is no friend of mine.”

“Now, now, don’t get impatient. A wash and a clean bed will work wonders. I suspect you’re more exhausted than you think.”

The pale square of light appeared ahead and enlarged to a doorway. It opened into the foot of a metal staircase. Lanark and Rima climbed slowly and painfully in watery green light. Ritchie-Smollet came patiently behind, humming to himself. After many minutes they emerged into a narrow, dark, stone-built chamber with marble plaques on three walls and large wrought-iron gates in the fourth. These swung easily outward, and they stepped onto a gravel path beneath a huge black sky. Lanark saw he was on a hilltop among the obelisks of a familiar cemetery.