WOUND STRIPES were small brass-coloured bars worn on the left tunic sleeve, added to the uniform every time a soldier was wounded at the Front. It is very common to see photos of soldiers with one or two stripes, and not infrequent to see men with three or four. They give the largely correct impression that to survive any length of time near the front line invariably meant being wounded.

Artillery and mortars caused the greatest number of casualties during the First World War, around 60%, while machine guns and rifles were responsible for 30% of deaths and injuries. With the increasing industrialisation of warfare, the number of shells supplied to the artillery was, by 1916, on a scale unheard of in 1914. Guns were able to lay down bombardments not only of greater intensity and accuracy, but also of almost unendurable length. With the Army Service Corps supplying the guns around the clock, bombardments, such as that which preceded the Battle of the Somme, could last many days.

Shells pulverised the front line and support trenches, catching troops as they marched up to the line. As men went into action, shrapnel burst overhead, and slivers of shell casing rained down, inflicting horrific injuries. The effect of such heavy shelling took a toll not just of the physical but also of the mental health of the soldier. Shellshock, a medical ailment not recognised at the start of the war, increasingly incapacitated men as their mental faculties became scrambled. In 1914, 1,906 cases of behavioural disorder were admitted to hospital, but by the end of 1915 this had grown to 20,327, or 9% of all battle casualties.

Officially, the army showed little sympathy towards shellshocked soldiers, and some men shot for cowardice were clearly suffering from extreme battle fatigue. However, doctors increasingly accepted shellshock as a condition of battle, and specialist hospitals or wards were set aside, such as those at Craiglockhart and Netley, for the treatment of officers and men with shellshock. By the end of the war, 30,000 cases of mental illness had been evacuated to Britain, and their treatment continued throughout the 1920s. By 1922, 50,000 pensions had been awarded to men on mental grounds alone. Recovery was often slow. In 1929 there were still some 65,000 soldiers of the First World War in mental hospitals. The official tally of all those who died during the war inevitably leaves out the thousands of traumatised former soldiers who committed suicide in the twenty years after the war.

Men who had lost arms and legs in the war were, for all to see, partially or completely invalided for life, receiving long term physical treatment and a small lifetime pension. Those who were wounded by poison gas were often less fortunate. Victims of mustard and chlorine gas often returned to the fight even though physically their lives had been blighted. Unless they were badly gassed, most men stood a very good chance of recovering, for counter measures against gas attacks quickly improved after the first attacks in 1915. Only 3% of casualties died and 2% were invalided, so although 113,764 men were gassed in 1918, only 2,673 died. However, while many men could and did return to the line and survive, their long term physical well-being was not guaranteed. Many men suffered relapses after appearing to recover, others suffered from chronic bronchial problems and the permanent loss of smell. Doctors routinely gave gas victims five to ten years to live after the war, yet despite the dire prognosis, many men had their paltry pensions reduced within six months of leaving the services. Owing to the depressed economic outlook, the Government's financial stringency meant some men lost their pensions altogether.

For those who were badly injured during the war, there would be many months or even years of interminable operations, convalescence, further operations, and physiotherapy. The Armistice spelt the end of the fighting, but the last of the stationary hospitals, at Abbeville and Boulogne, did not close until 1920. In the same year there were over 18,500 beds still carrying the most seriously wounded from the war and 48 special mental hospitals in Britain. Hospitals such as The Royal Herbert at Woolwich continued to have wards full of soldiers recovering from their wounds until 1921 and 1922. Even as late as 1928 there were 5,205 first issues of artificial limbs to soldiers.

The long term mental and physical fallout from the war was enormous. Even on the eightieth anniversary of the Armistice, there were hundreds of soldiers who continued to suffer significant pain and discomfort from injuries received not just on the Western Front, but also further afield in Gallipoli, Mesopotamia, palestine, and Salonika.

Jock was 19 years old when he embarked for France in May 1916, a private in the 1/4th Gordon Highlanders. He had served just two months on the Somme when a shell finished his military career, and he returned to England in July. At 102 years old, he recalled the day war changed, but failed to blight, his long life. Recovering from wounds, Jock became an artist for Life Magazine, living in America for many years.

All my life I have had hunches that something was going to happen. I had no idea how or why, but I had that feeling, something was in the offing. We were going up Mametz Valley – known as Death Valley – towards the line near High Wood, and I became quite fidgety. I turned to my friend next to me and said “What a nice morning for a cushy blighty and home”, a cushy one being a nice wound that would get me back to England. The next thing I heard was one stiffening bang and I went down and when I came to, I was lying on my back with both legs in the air. I couldn't move but I looked and saw that my right foot had gone. Shrapnel had hit behind the heel and took the sole clean away leaving my big toe dangling round and round. When the RAMC men came up, they just casually cut the toe away and threw it on the roadside.

An ambulance came down, and then by stages I was taken to the base hospital at Camiers, where they put me on the operating table. There were a dozen tables in the theatre and all of them were occupied. I said to the surgeon, “I don't want to lose my foot if I can manage it”, and he replied “We'll do what we can.” They amputated my foot through the ankle. It was hopeless. The foot had to go and that was that, but I can assure you it was no easy job, it was extremely painful and if I ever cried in my life, I cried then, I'm not ashamed to say so.

I was nineteen years old and I had just received this injury which would finish me throughout my life from quite a few things. At my age, to have that injury was quite a shock. It meant I would have to adapt my life in many ways; luckily I was never much of a sportsman apart from fishing, but even so I had to make the best of it. I had been lucky, though, because the shell had wiped out a good part of my company.

I did not look at the dressings. I know there were bandages and there were tourniquets and tightenings and things like that, but I wasn't too happy about looking at the rawness so I just let them do what was necessary. I was back in England at the Rowntrees' Convalescent Hospital in York, and the nurses there were very gentle, and seemed to take their work in their stride. The sights they saw, I could never get over that, yet we got nothing but the best treatment. I had to have further amputations higher and higher up the leg; the second one took my leg off to within four inches of the knees and that was very, very sore, I can assure you. A spot of gangrene had apparently set in, a “spot”, that was the word I overheard and it frightened me, but they worked on it right away and did a wonderful job. Once again there was a lot more crying, good hefty blubbering, for it was more than I could stand. The hot poultices were incredibly painful and then there were the dressings. These used to terrify me in every way because the nurse had to pull off the blood soaked bandages and they stuck to the wound and tugging on them only took away some more of the flesh. You could hear other men having their bandages done too, and you could hear them yell and moan. Aye, it was a rotten job, that, an ordeal I dreaded.

One nurse, Mary Sutherland, had a great effect on my life. She was my nurse and she certainly looked after me. She sat with me day and night until I came round after the second amputation, speaking only words of comfort as the pain subsided, helping me through this traumatic state of affairs. Later on, she used to wheel me to the shops in the bath chair and we'd go for a coffee. It wasn't a case of attraction, not at all, I was an apprentice printer and I'd come from a different walk of life. The question of any feelings didn't enter it at all, it was just that she was very good at her job. I missed her very much when I went south to hospital in London. Many years after the war, I made contact again. She had retired to Dorset and I arranged to visit, but she died about a week before I was due to go.

Of course, you felt that most of the nurses came from what we would call then a better class. They were most of them ladies of good breeding, they came from good families and we treated them with very great respect. Later, I was transferred to Nunthorn Hall, in Scotland, the home of Lord and Lady Hulme. They had given over part of their house for convalescent soldiers, and the nurses there used to take us out shooting. We would be wheeled out in bathchairs to shoot pheasants with double barrel shotguns, feathers flying everywhere, with the nurses standing behind us with their fingers in their ears.

The nurses were very proud of their uniforms and loved the occasion of taking us out, a dozen of us wounded boys, on a trip to the cinema, and of course we got in for nothing. Being a wounded soldier, you were a bit of an eye-catcher. Crowds would watch soldiers being moved, and the nurses felt very much appreciated. The uniforms were very important, it gave them a sense of purpose, a challenge. People would stop you in the street, or come up and talk to you, get you a packet of cigarettes or chocolate. If you went to the theatre for the afternoon performance, if you were in a wheelchair like me, you were always wheeled down the gangway until you got almost to the stage. If the show hadn't started, you could often see the curtain move and the girls looking at you, oh, you were quite an eyeful. It was nice to be in a wheelchair and being the wounded soldier, but the thoughts were there about having to live with it when the war was finished and that was a bit of a worry.

After the amputation came the fitting of an artificial leg, when I was sent down to Roehampton, the limbless hospital in London. You always got blisters on the stump and they could be very awkward, but you can gradually get used to them with treatment. The blisters came while you were walking, if you had something out of place or a fold or a little crumple in your trousers. If the blister broke, you couldn't use ointment because the more ointment you used, the more pain, and the more the sore spread. It could be a very small sore, but then it could turn into one the size of a halfcrown, in which case you had to take your leg off and go into a wheelchair until it dried up and healed.

There was no hard and fast rule to treat blisters. The nurses were as ignorant as we were, and we all learned the tricks of the trade as time passed. The nurses knew nothing about artificial limbs either, that was the fitters' job, the men who made the leg and fitted it. If there were any blisters, the fitters noted it, then marked the stump, replacing the stump into the artificial leg which transferred the mark onto the inside of the leg bucket. The fitter knew then where to cut a little wood out to make the adjustments.

As well as blisters, stump pains were a regular problem and I can assure you they could be very, very trying. They were also called phantom pains because they were something that the medical profession knew very little about, let alone the nurses. The pain was pretty much like toothache on a grand scale. The nurses knew there was plenty of pain there and they were very sympathetic, and gave us pain killers, but they didn't know just how bad they were.

I remember I was coming out of Lloyds Bank on the corner of Shaftesbury Avenue and Piccadilly Circus when I managed to step badly on my artificial foot, and there was a crack. Well, I was on sticks and when I walked away, my foot and my sock came out of my trousers and fell onto the pavement. I managed to pick up my leg but was left with my foot in my hand, hopping around. Now if you want to collect a crowd in Piccadilly Circus at one o'clock, do something like that and you'll collect one pretty quick. I was taken back into the bank and the under-manager put me in his car and took me back to Putney, to my home. I was a wounded soldier, you see, that counted for a lot.

Guy Botwright had never wanted to serve at the Front, but out of a sense of duty he had gone to France in 1917. The horror he saw inflicted deep psychological wounds, and he was returned to England with shellshock after an explosion close by knocked him unconscious.

My job was to organise all the transport of food and ammunition to the front line. The company would go to the railhead and the ammunition would be unloaded and then taken to a dump. From there it was taken up the line, and I would ensure it was going to the right place by going up the road with a column. The Germans would often shell the dumps and the roads – the biggest fire I ever saw was a dump of cordite in flames. And there were horrible sights, too. I remember once, a battery had been hit and the mules pulling it were splattered all over the place, the fire power of artillery and machine gun fire, you can't imagine. By far the worst were the wounded; when a man was badly wounded, we'd cheer him up and tell him it's all over for you old chappie, you'll go home. It is difficult to describe my feelings so many years on, but you live day to day, when you know your life at any minute could be carved to bits. I can say that I suffered fear from my toe to the tip of my head but I had a job to do. Out of the line, in rest, there were times when suddenly I thought “God, I can't go back to it”, but you did go back to it, you had to go back to it. I was an officer, I had to, so I would get ready, put my jacket on and I would fall into line, as best I could.

I rarely had to go into the line, but I know I was in part of a trench that was being dug when suddenly everything went black. A shell had landed very close to me, although I don't remember feeling any pain of any kind whatever. The next thing, well, I just came round and to my utter amazement I was in bed in hospital in England. How I got there I haven't got the foggiest, nor how long it was from the time I felt nothing to waking up and finding myself in bed, days, I feel pretty certain. I can only imagine I was unconscious all that time, I have no idea, the whole thing took time to sink in – I had shellshock you see.

Well, I didn't care what happened. Any desire to continue did not exist, I went to bits. It would have been far better if I hadn't known, you see, but of course they couldn't keep me in hospital without letting me know that was what it was, I mean if I hadn't realised that it was shellshock, or hadn't been told so, I don't quite know what I would have imagined had happened, because my only physical injury was the very top of one finger gone.

I didn't care whether I lived or not. In the first stages, you're much more likely to shed a tear, to feel the depression, oh yes, the depression, I would put that down as depression. If I got a sudden depression, well, it would depend on my state at the time, I might be able to throw it off. The nurses were wonderful, they'd ask a question and by what sort of answer they got, they'd know exactly what was in the air. They were well-trained but then the hospital staff had dozens of people in exactly the same condition.

Each day I thought, “oh dear, another day, oh Lord.” It was self-pity, even knowing how lucky I was could make me burst into tears, I had to help myself but I also had to be helped out of the situation. What was to be done God only knows, was the sort of idea that one had. You lived hour to hour, I don't say day to day for the simple reason that Tuesday or Wednesday didn't exist as such. You didn't know where you were, you would, if you had only shellshock, have no pain as such. It would simply be that the mind would not work, you didn't know day from night and you didn't know about eating, whether it was lunch time or tea time. It's a shocking state to get into, being mentally wounded, I wouldn't recommend it.

I did not venture from my bed for anything, good gracious, no fear, not until things began to settle down, then I might be told to get up for 10 minutes and somebody would come and help me out of bed to a chair. They would force you to do it and rightly, too. They'd stay there and help because my legs would flop, your legs would let you down, you never quite knew when they were going to let you down. Luckily I was never in one room alone, thank goodness, because it helped to be in a ward with other people even if they are ill too, it is a help, you know that you are not on your own. I was not embarrassed by my condition. You never thought yourself an officer, you thought you were you. I don't think being in the army came into my life until I was much better, rank did not come into it at all, we were all officers but we were pals together under those circumstances.

There was very little shakiness, my hands did not shake, on the contrary, for a while I had no real movement: it was the mind, that was the real shock. I never had nightmares, I never dreaded the night coming on, but I did get flash-backs for many years. They could happen at any time, if I was in a street, if there was something interesting I would forget myself then I would be all right, but then I might think “Well, it isn't raining but it might do”, or I might sneeze and think that I had a cold coming on and that would start things off, you would feel a depression coming on. If something reminded me of incidents in France, if I had made a botch up of anything, that would come back at odd times to depress me.

I was still an officer when I was called to a board meeting at Chichester to be discharged. There was a table of seven officers and the chairman said “What are you going to do when you are discharged?” and I remember saying “I have not the slightest idea, but I want an open air existence”. I decided on forestry. It was the end of the war and it was the beginning of recovery in a sense. I made up my mind, “The war has now ceased and I'm going back into civilian life”. The war had so broken up my future, it had been such a shock, I decided I would never talk about it or write or read anything about it and I never did.

The question “what if?” had a lifetime's significance for former artilleryman Fred Tayler. What if Fred had walked away from a shell explosion in the last weeks of the war? How radically different would the course of his life have been? As it was, the shell smashed Fred's left leg, making an amputation inevitable. His future uncertain, Fred returned to England and a hospital bed in Carlisle. However, his injury guaranteed one thing: he would meet Beattie O'Neill, a nurse and fellow Londoner. She devotedly looked after Fred as he recovered, care soon turning into romance, which turned into very happy sixty-two year marriage.

I had been attached to Headquarters for quite a time during the latter months of 1918. The war had more or less become open warfare again, and the infantry were moving steadily forward, but at headquarters we thought we were a long way behind any action. I remember there were eight of us in an empty house, when someone came in and said “Come and look, you can see the fighting”. We all rushed out of the door and up the path that led to the road, and sure enough, up on a hill you could see them bayonet fighting, the glints of sun shining on the steel. The troops we had seen marching up past us a little earlier had come back over the hill with the Germans behind. We were lined up on this path and didn't realise that we could naturally be seen as well, when suddenly over come two shells. The first one fell just in front of the house and as we went to get up from ducking, the second landed on our side. I heard the first but not the second shell. unfortunately, I was the nearest to it when it burst, about six feet away. Down we all went, but when the smoke cleared, the others got up and ran into the house. I tried, but found I couldn't. I was in no pain, but as fast as I stood up, I fell down again, so I crawled into the house and went to lay against a wall which I thought would be the safest place if any more shells came. Then I rolled over on my back and looked down at my leg and to my surprise I was looking at the sole of my foot.

The others were in the cellar when somebody called “Who's up there, anybody?” I said “Yes, Tayler”. They told me to come down but I replied that I couldn't move so they came up to see what was wrong. There happened to be a doctor in our group, but there was little he could do. He asked me whether I felt any pain, but there was no pain – it didn't hurt, and there was no blood, except a little on my shoulder, but not on my leg although my leg was the wrong way round. They were trying to get the front door off to use it as a stretcher when some German prisoners were coming down the road and were ordered to carry me back to a first aid post.

When I arrived, there was a padre I knew standing just inside and he looked round and spotted me. “Hello, Tayler, what are you doing here?” I said I thought I'd got in the way of a shell and we laughed. He told me not to worry, he would get in touch with my parents and said he'd write and let them know I'd been wounded and that I'd be writing. At the aid post, they dress what they can dress. They took my jacket off and got the bit of shrapnel that was sticking out, but they couldn't do anything for my leg because the leg was intact, the skin wasn't broken.

I wasn't capable of thinking about much, about what might happen to me. If there'd been any blood, I think it would have made me wonder more, but there was no blood. I suppose not being able to understand what had happened, or how serious it was, perhaps it didn't affect me quite so much. I was placed in an ambulance with a corporal of the RAMC. He seemed to be lightly wounded and had walked down to the dressing station. He was moaning and groaning a bit. He told me he could look after other people's wounds, but he was terrified of being wounded himself. Unfortunately when we got to the operating theatre, the poor chap was dead.

At the hospital, I tried to look around 'cos it seemed there were so many operations taking place at once. Someone came to examine me. I don't remember passing out, but I came too when they put me on the table to be operated on. I remember seeing this man and I tried to raise myself up, to look around, but I was pushed back down again on my shoulders, and somebody put their hand on my head. I hit out, I hit the poor chap in the face, there was no reason to it, it was just that something was stopping me lifting my head up, so I hit them, then I was off.

I had an operation but I didn't know what they had done. I was taken to a ward and the next day a train arrived to take the wounded down to the base. They didn't seem to want to take me at first, but they were shouting “Any more for the train?” The chap looking after me said “I've got one here, but he won't be long”, and I thought he meant I was going to die. I don't know if that's what he thought, but I said “I'm all right, I'm all right, I want to go”. Whoever was in charge of the ward said “Oh, take him out, take him out”. I got to a little window with a girl sitting behind it and she wanted to know my name, address and army number, but I couldn't remember a thing. This poor girl was asking me questions which I couldn't answer. I thought I was going to be left behind, the others were gradually moving on, getting in the train, and then I suddenly remembered, it came to me who I was and my number and everything, and I called out.

My particulars were taken and I was wheeled out to the ambulance train, no seats, just three racks on each side of the carriage. As they lifted me up, a corporal receiving the patients said “What's this one?” and a chap looked at a label on me and the answer came “Amputation”. Well, that was the first I knew that my leg was off, it was quite a shock. I didn't realise because there was no sensation that it was off and I wasn't in pain. I just wondered how long it would be before my mother got to know and how it would affect her. That was my first thought when I was injured, what would my mother think, then you suddenly realise that you're going to be a different person. My leg was intact but smashed. I was hit half-way down the calf, half-way down the leg itself, but the damage was so severe that the actual knee was shattered, so that was why they had to take my leg off above the knee.

I was taken across the Channel but because they didn't like you to be too near home, the inconvenience of so many visitors, they sent me up to Carlisle which is a long way from London and my home, there was no chance of visiting me there. I was the only Londoner there, so there were all sorts of different brogues. One day, the matron came in with a nurse and said, this is a new nurse on this ward and she comes from London, it might be a bit of a help for you. I thought that was very nice. So she came and had a chat, after she'd been round all the patients she came back to me and we had our little chat, and our friendship just grew and grew.

Her name was Beattie O'Neill, a lovely girl. When I got onto crutches, we started going to the cinema in Carlisle, but we had to go out of the hospital separately. We daren't be seen because the rules were that patients and nurses don't mix. We couldn't meet until we got to the cinema, same with going for a meal, we would not meet until we both got to the restaurant. We started going out and when I left hospital we married, married for sixty-two years we were.

Harry Wells was as old as the century, literally. Over-exertion by his mother at a New Year's Eve party brought Harry into the world as the new century dawned. Eighteen years later, Harry was in the trenches in France, one of the thousands of soldiers just old enough to train and still see action in the First World War. Yet his short sojourn at the Front nearly ended his life, when, badly gassed, he fought for over two years in hospital to regain his health. He was finally released from hospital in October 1920.

We'd been in the line for over a week and all the boys were saying how quiet it was. There hadn't been any shells for a couple of days, and in all the time we had been in the trenches there had just been the occasional shell to let us know Jerry was still around. At the time, an attack was being prepared and a lot of reinforcements were coming into the line. The idea was for these new troops to go over the top at first light, followed by the Fusiliers of my battalion.

We could hear the troops as they filtered up the line, and the guns and limbers further back, the steel wheels on the French roads. The Germans must have heard the same thing and guessed what was happening, because all of a sudden they started blasting with everything they'd got. High explosive and gas shells were raining down and the trenches were being blown to pieces of course, so instructions came round to go down into a gas-proof dugout big enough to hold up to a hundred men, I would guess. We'd been down there about an hour when a few wounded men began to be brought down, one I remember with his arm off. Unfortunately, no one thought, but some of these men had had liquid gas splashed on their uniforms and down below in the warm air given off by our bodies, the liquid gas began to evaporate. We had begun grovelling about before anyone realised what was happening. We were told to put our gas masks on, but by this time we'd more or less gassed ourselves.

After a couple of hours, we were ordered out into the trench. It was a little after dawn, but we found it bright daylight and we simply could not keep our eyes open. I knew I had been gassed but I was hoping in my mind that it was only just a whiff of gas and perhaps a bit of fresh air might blow it away. However, the longer we stayed out in the open air, the worse the effects got until we couldn't open our eyes at all. There were dead bodies in the trench mixed up with the earth and we walked over them as we had to feel our way around. Somebody gave me someone's shoulder to hang onto and we were led out of the broken trenches some three or four kilometres to a first aid post, where we were sorted out into badly amd less badly wounded, and those playing up. I couldn't see what it was, but from the noise, it sounded like the floor of a warehouse. I got the impression there were about 200 men or more, myself included, lying on the floor on stretchers waiting to be taken down the line.

Just lying there had quite a nasty effect, because I was only a lad, and to hear these men crying out with the pain, crying like children, not so much from wounds but from the flesh burnt by mustard gas on the skin, was awful. Mustard gas used to attack the warmest parts of the body and would take the skin off as if you had scalded yourself, so you can imagine what that was like under the armpits, the crotch, that sort of area.

Some trucks were provided which took us down to an American hospital at Le Treport, the 16th Philadelphia General, I was later to find out. Our eyes were covered, but as we entered, I always remember an American nurse's voice saying “Good God, they're sending babies now to fight their war.” I looked very young in those days. I was very fair and very fresh-looking, eighteen years old. We knew we were in good hands, and that was a relief. I knew I stood a good chance of living. Having no experience of being gassed or wounded, you didn't know what was going to happen but they got down to the treatment of my eyes straightaway. After a couple of days, I was able to open them and see a little, but I had to have a shade over my eyes all the time for the next year. The only treatment that I can recall was we were given something called Mistexpect. This was a sort of mixture which helped break up the phlegm which we brought up, as well as easing the coughing caused by the gas.

After about two weeks, what they called the walking wounded were cleared out to the trains, onto the ships and over to England. Now in those days they put you on a Red Cross train and the train went straight onto the ferry and off again at Dover and on towards, in our case, London. We actually stopped at Clapham Junction for a few minutes to get clearance to carry on up north. This was where I was born and my mother still lived there, so I hurriedly borrowed a pencil and wrote a postcard saying that I was home in Blighty and that I would drop her a line later. I threw it out of the window and somebody picked the card up from the platform and took it to my mother.

While I had gradually got my sight back, the gas which I had inhaled had meanwhile done near-fatal damage to my chest, affecting one lung which they told me had collapsed. The gas itself began burning its way out of my chest, forcing bits of rib through the skin. It made an open wound which the doctors could only hope to syringe, hoping to kill the germs and cure the gas poisoning inside. It was lysol they used all the time, I think. They would syringe me out every morning and then use something called a Silver Stick, a whitish substance which caused very severe tingling as it burnt off the dead flesh but importantly kept the wound open. They would then bandage me up again from top to bottom using what they called a butterfly bandage, then the job was repeated again later that day.

My open wound was, if anything, getting worse, and slivers of the rib were coming out. I had a high temperature and I was going in and out of consciousness and was seriously ill. Eventually I slipped into a coma and my mother was sent for, to see me for the last time. She received two telegrams that day, one to come and see me, the other to see my brother who was in Carshalton Hospital. He was just fourteen and he was ill with peritonitis. I was in a coma for about a fortnight, although when I awoke I assumed I had only had a long night's sleep. My brother died at that time, unfortunately, they couldn't save him.

Nurse Blake, a Welsh girl, she was the one who really pulled me round. I think it was the motherly instinct, because I looked so young at eighteen, very fresh, clean shaven, almost babyish. She tended to me the whole time, talking to me. You are inclined to go off into a stupor and give up, you know, say “why worry”? You are so ill you let go, as it were. This nurse kept on at me and saved my life by just being there, talking, holding my hand, keeping me occupied. “Do you want anything? Can we get you anything? Would you like a cup of tea?” Just like this until the day you suddenly sit up in bed. This did not mean I was better; the process of bandaging and cleaning the wound continued for many months. It was only when the last surgeon decided to have a go at carving out the entire infection, that I made permanent improvements. He cut away the infection like pieces of cheese, and used the Silver Stick to burn away any further dead flesh. The wound gradually healed up.

Looking back, I wonder how I put up with the whole ordeal. I suppose part of it was the stiff upper lip. The pain was bad, but it was recognised that it was for a man to be a man and not to show pain – and when you are eighteen you so want to be a man. We found by experience that the harder the nurse was, the better she did her job. We didn't much care for these nurses, but if she took no notice of whether she hurt you or not, she was generally much more efficient than the nervous girl who feared hurting you.

The efficient nurses were the Queen Alexandra nurses, the military nurses who were fully trained and knew what they were doing. They would tell you not to be a baby, or I would hear them say to other patients “that's nothing much”, that sort of thing. The others were volunteers, the VADs, and of course they were unsure because they were not qualified nurses. But there were thousands of boys who had come home injured, and these nurses were doing jobs they ordinarily wouldn't. On one occasion, an inexperienced nurse had syringed me but she got a bit close to the lung, because I found lysol was coming up my throat. It frightened me almost as much as it frightened this girl, because she knew she wasn't doing it right and she was nervous. There was a bit of bleeding and I ended up swallowing much of the liquid, but it was one of those things, and it wouldn't have been fair to blame her. I say you can never speak too highly of the work both the VAD girls and the army nurses did, and the hours they spent looking after us.

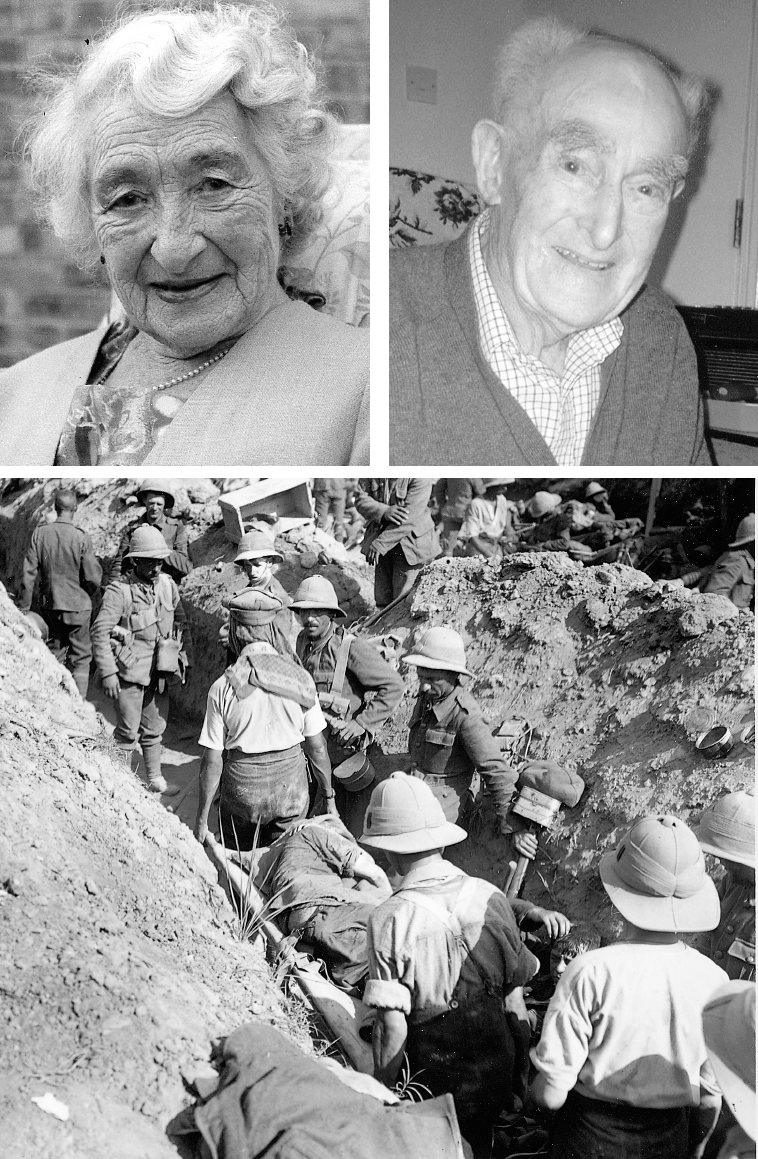

Horace Gaffron in 1998 and 1916. He was to lose his foot to a shell burst on the Somme.

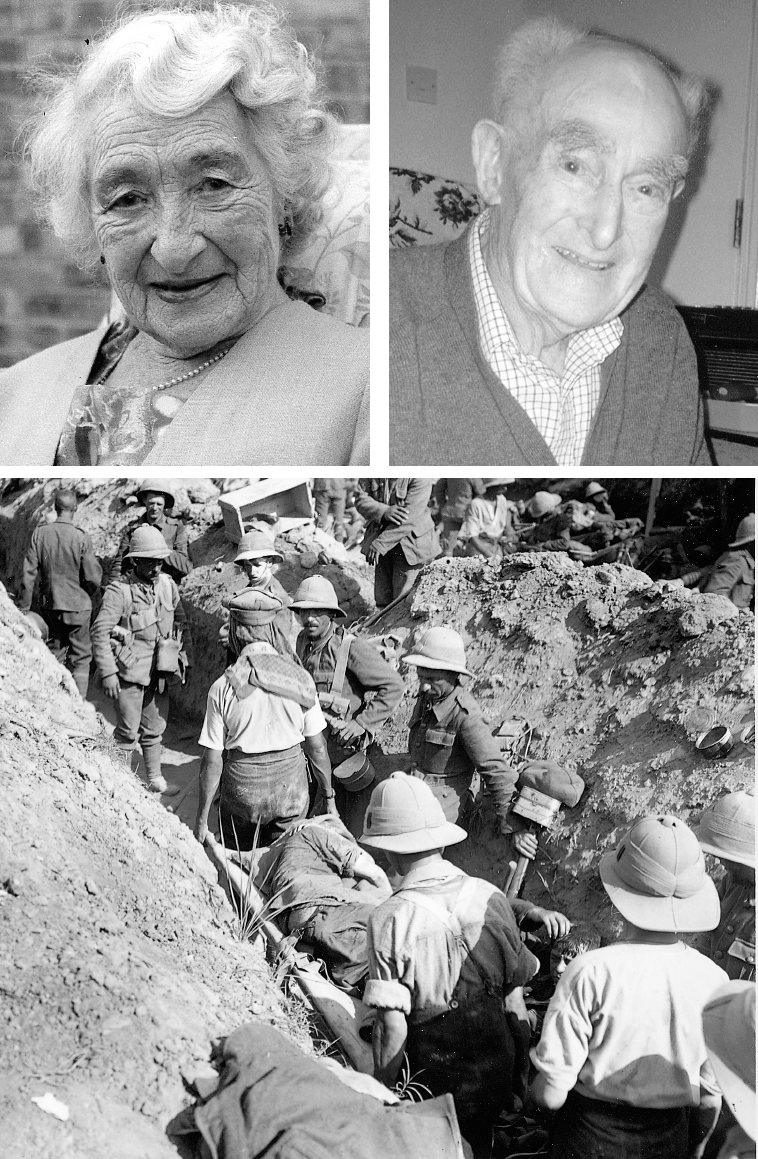

A lightly wounded soldier clearly in pain receives a temporary dressing before his removal to a Casualty Clearing

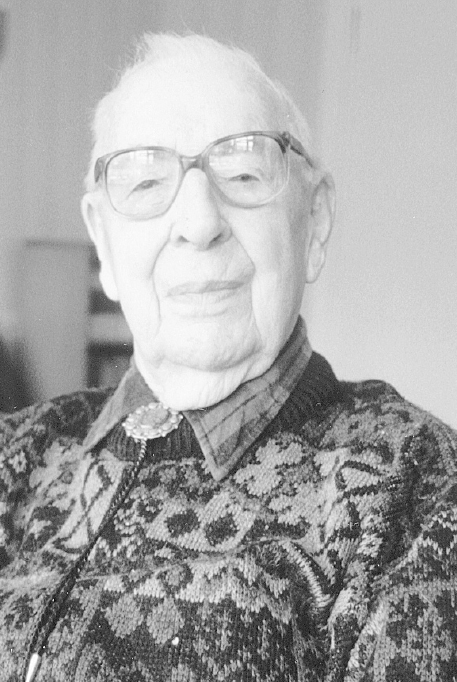

Those who were badly injured during the war would experience many months or even years of operations, convalescence and further operations.

‘She sat with me day and night until I came round after the second amputation, speaking only words of comfort as the pain subsided.’ Horace Gaffron and nurse Mary Sutherland, who helped Horace through his amputations.

A German daylight bombing raid on London, July 1917. Two victims are being taken home from hospital with a nurse. Civilians were not frightened into submission and no prized targets were hit. However, women and children had become legitimate targets.

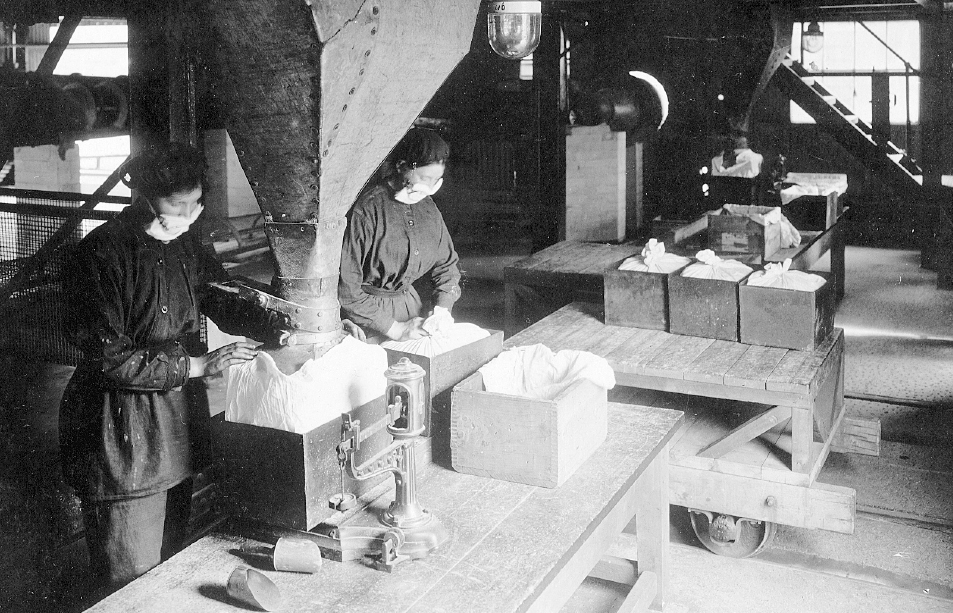

Women bagging TNT, a job which turned the girls' faces and hands a bright yellow, giving rise to the nickname “canary girls”.

Cleveland Road, Hartlepool. Serious damage to private houses was caused during the German bombardment. People in other parts of the country found it difficult to believe that the attack had really happened.

Cora Tucker 1917 and 1997. A lady living near Cora was killed by a shell splinter during the bombardment.

Mary Jollie in 1997 and as a General Nurse in 1918.

It was discovered that when maggots were introduced into a gangrenous wound they consumed the gangrene and the wound would start to heal.

Strict discipline was enforced in the wards by the Ward Sister. All beds had to line up and even the castors had to be positioned the same way. The ward shown here was at Redlands War Hospital, Reading; the room is a school classroom today.

Helping wounded soldiers recover involved recreational activities – here, a group enjoys a game of cricket away from the clinical smell of the wards.

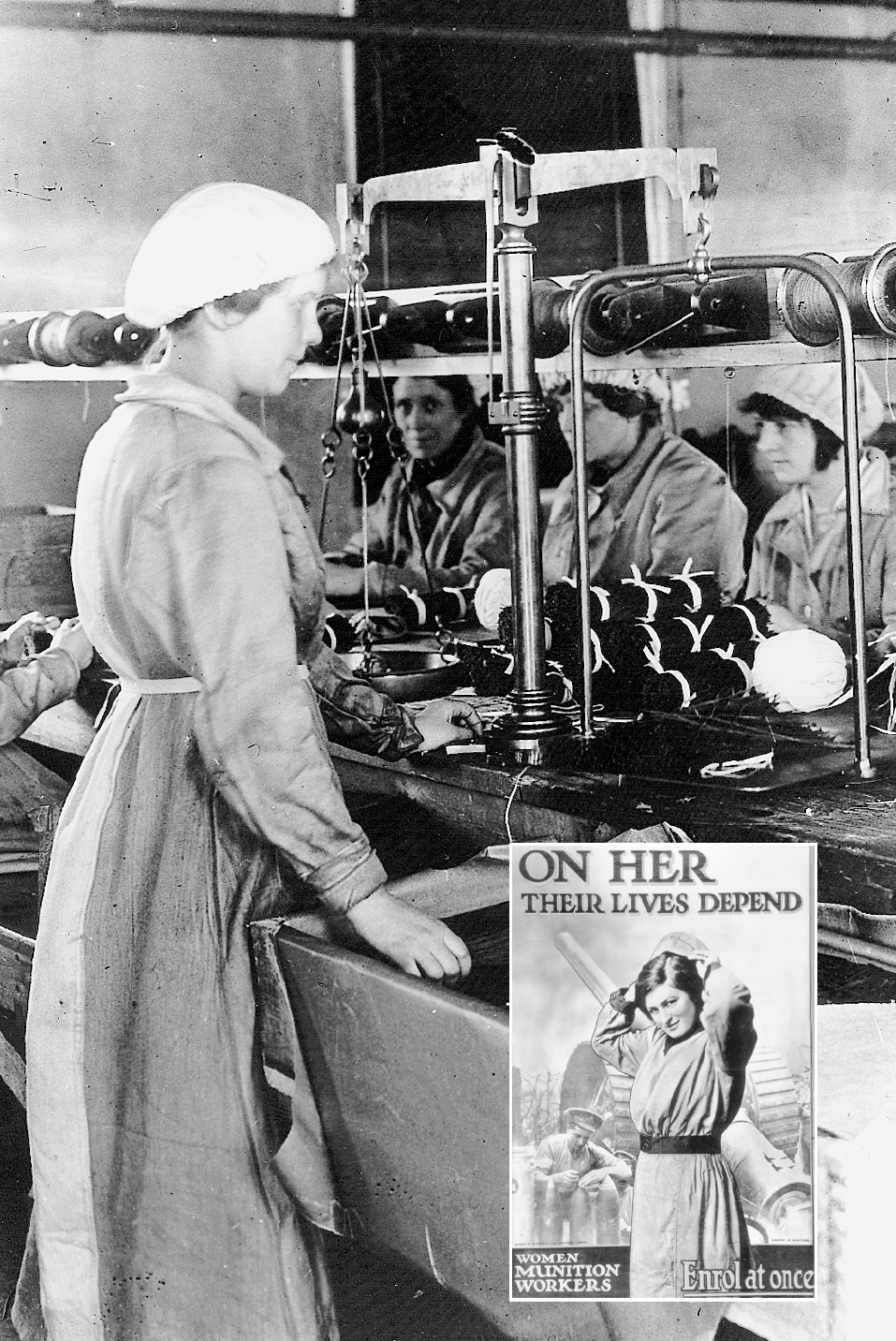

Munitions workers cut up and weigh cordite.

Daisy Collingwood, aged 101, and right as a munitions worker, 1917.

Working with munitions was highly dangerous and explosions were not infrequent. The worst, at Silvertown in 1917, devastated one square mile of London's East End, killing 69 women and injuring another 72.

British prisoners marched off the battlefield after being taken during the German Spring Offensive of 1918. Their lives spared in the heat of battle, they would spend the next eight months on food rations which deteriorated daily, as the Allied blockade of sea ports gripped Germany.

British prisoners entrain for Germany.

Bill Easton, posted missing after the German onslaught in March 1918. He had, in fact, been taken prisoner. The above form is dated 18th April, leaving his parents to wait anxiously for further news.

A mixture of British and French prisoners arrive at a POW camp in Münster.

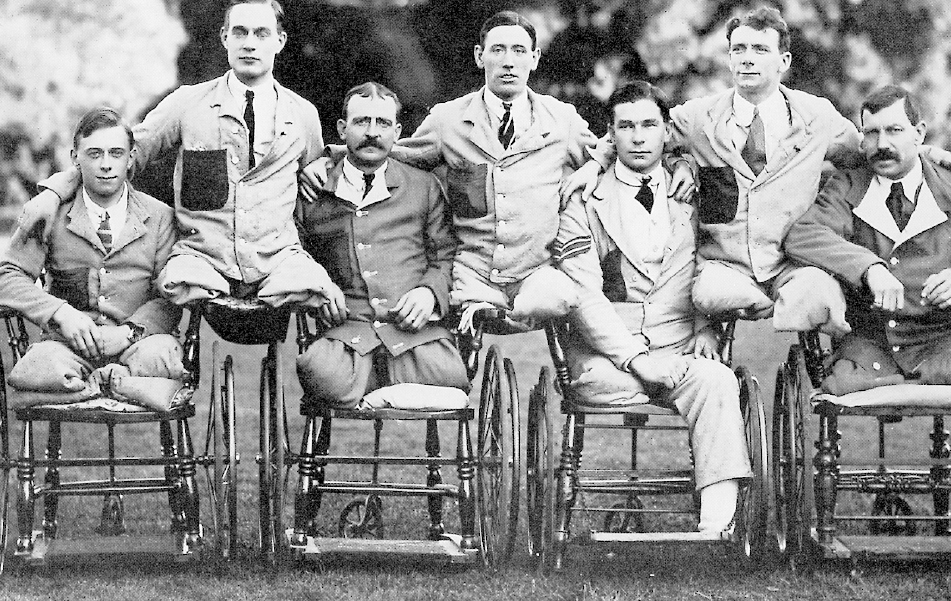

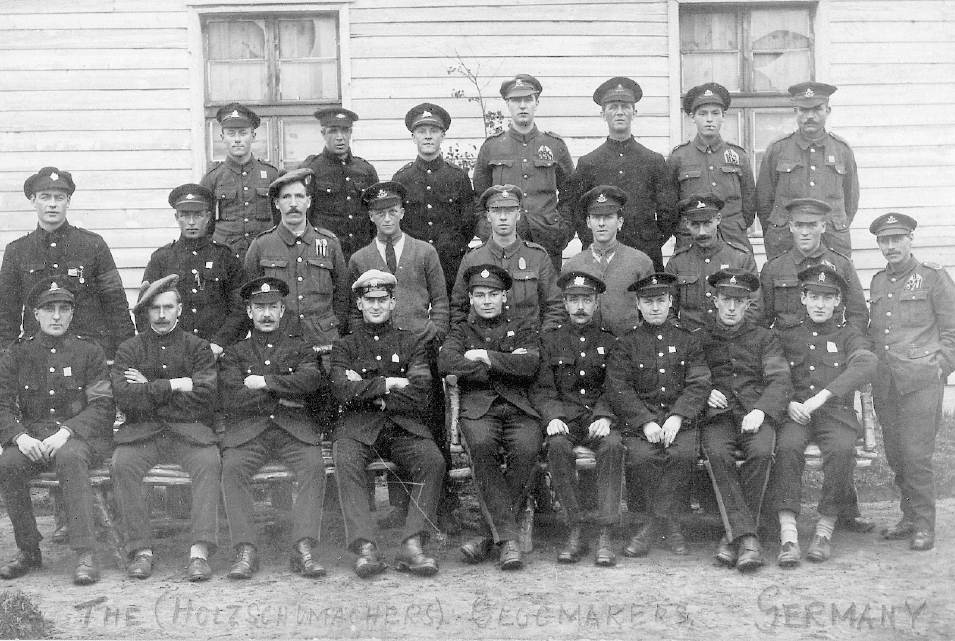

Jack Rogers (5th left, sitting) with fellow prisoners, all of whom were given the task of making wooden shoes, Jack's prewar trade.

An extraordinary, and probably unique, photograph. Bill Easton is seen with cigar and beer in his hand being toasted by men of the 625th Sanitäts Kompany. Bill willingly stayed within the battle area to help remove the wounded and was made honourary sergeant in the process.

Bill Easton 1918.

The German offensive finally ground to a halt in May 1918. The Allies took the initiative in August and began to push the Germans back, with spectacular results. By October, the trenches, which had so characterised the Western Front, were abandoned as open warfare resumed.

‘Prisoners were docile and were thankful they were prisoners. I didn't feel any anger towards them, rather, I just thought what an untidy-looking lot they were.’ Andrew Bowie 1917.

‘We were told by a despatch rider that the war was going to end at 11 am... my first thought was “So I'm going to live.”’ Frederick Hodges 1918.