Principle 3:

Responding with Sensitivity

Learning the Language of Love

Here’s how the early mother-infant communication system works. The opening sounds of the baby’s cry activate a mother’s emotions. This is physical as well as psychological. Upon hearing her baby cry, a mother experiences an increased blood flow to her breasts, accompanied by the biological urge to pick up and nurse her baby. This is one of the strongest examples of how the biological signals of the baby trigger a biological response in the mother. There is no other signal in the world that sets off such intense responses in a mother as her baby’s cry. At no other time in the child’s life will language so forcefully stimulate the mother to act.

—William Sears, MD, “Bonding with Your Newborn,”

in Attachment Parenting: The Journal of API

Of the eight principles of parenting, we believe responding with sensitivity is one of the most important. It is the foundation that strengthens all the other principles, and it is the basis for developing a secure attachment relationship with your children. Sensitive responsiveness implies the ability to set aside one’s own needs for the needs of the baby; it presupposes a change in consciousness of the parents and the capacity to feel empathy—to see the world through the eyes of their child. Babies communicate their needs in many ways, including body movements, facial expressions, and crying. They often try to tell us that they need our attention long before they begin to cry, if we only understood their attempts. As you learn to understand and respond to your infant’s cues (signals), through consistency you will build a strong foundation of trust and empathy.

Researchers have found that human infants are born with the expectation to be responded to rather quickly. When responses are consistent, babies begin to learn the first lessons of empathy and trust. Often parents wait until their baby is crying before responding, and then they have a very distraught baby on their hands who is much harder to calm down. For instance, a hungry baby (or one who needs comforting) will typically turn his head toward the breast and open his mouth wide, he may put his fists in his mouth and suck on them, or he may simply start making sucking movements with his mouth. By paying attention to his subtle signals, you will begin to understand what he is trying to communicate long before the tears begin to flow. If a baby fusses and seems restless but quiets down when you pick him up, you are fulfilling his need for closeness, warmth, and comfort.

Neuroscience studies are showing that there is more to these interactions than meets the eye. A mother and baby’s brains can actually become synchronized, and it is that synchrony that they call neural resonance. Neural resonance very simply means that mother and child are better able to read and interpret each other’s emotions, and brain waves become very similar. In her book The Bond, Lynne McTaggart describes her experience as a first-time mother. She felt ill prepared, even though she studied pregnancy, birth, and parenting with the same passion as an investigative journalist. She describes how she, alone, was able to calm her crying baby, no matter how much her husband tried. She later realized that she was—in a very real sense—a “metronome” for the baby’s brain waves: “Our brain waves had coordinated into a single undulation. . . . Opening yourself up to a pure connection with someone else, as occurs with someone else, as occurs with a mother and child, creates a neural resonance effect between you.”

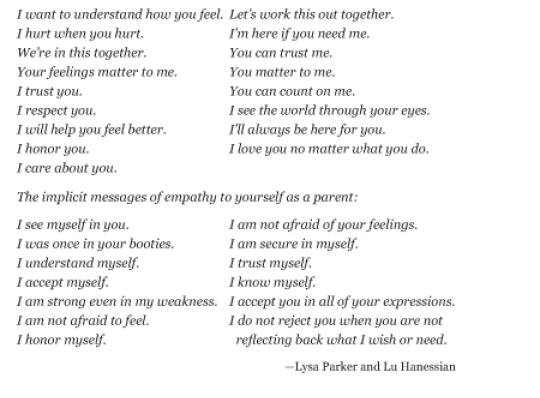

The word empathy means experiencing as one’s own the feelings of others, or the capacity for this. When you respond to your baby (or any other human being, for that matter) with empathy, you convey these implicit messages:

Building a Strong Connection with Your Baby

Harville Hendrix, a renowned psychotherapist, and his wife, Helen Hunt, wrote Giving the Love That Heals to help parents understand how imperative it is that they strengthen the attachment with their baby. This advice comes from many years of experience working with individuals and couples using Imago therapy, which they developed (they are also the parents of six grown children):

For the first eighteen months after birth, your baby is totally dependent. He is bonding with you and learning that his needs will be met. During this period, the most important thing you can do is be reliably available and reliably warm. This means responding to what he needs when he needs it, regardless of whether it is convenient. When you do this, you are ensuring that your baby will survive and that he will maintain that sense of connection with the universe that is the foundation of his future security in the world.”1

1 Hendrix and Hunt, Giving The Love that Heals, 201.

Mothers of securely attached infants tend to be more sensitive, reliable, and accepting of their infants.2

The synchrony, or dysynchrony, of interactions between parent and infant have been found to determine security of attachment. Mothers who were found to be inconsistent, intrusive, and overstimulating were more likely to have insecure attachments with their babies.3

Parental warmth and positive expressiveness with children was strongly correlated with children’s development of empathy and social functioning, especially in older children.4

2 De Wolff and van Ijzendoorn, “Sensitivity and attachment.”

3 Isabella and Belsky, “Interactional synchrony and the origins of infant-mother attachment.”

4 Zhou et al., “The relations of parental warmth.”

Building a strong connection with your baby involves not only responding consistently to her physical needs but also spending enjoyable time interacting, talking, and playing with her, a natural and fun way to meet her emotional needs. When your baby gazes into your eyes, it is her invitation to you to connect with her; she may smile at you with the expectation that you will smile and talk back to her. Later, as she begins to understand the rhythm of the sounds of language, she will attempt to make her own sounds to communicate back to you in the form of babbling, expecting you to talk back. Hendrix and Hunt advise that parents meet the emotional needs of their baby by speaking in a soothing, soft tone of voice:

As the baby begins to experiment with facial expressions and sounds that will eventually enable her to verbalize her communications, it is important for the parents to validate her nonverbal communication by mirroring them. This means reproducing the sounds and expressions in order to allow the baby to gain confidence in her experimentation. When in doubt how to mirror, smiling works wonders.5

5 Hendrix and Hunt, Giving the Love That Heals, 202.

Mothers who accurately perceived the urgency of their infants’ cries consequently responded appropriately. The benefit to infants . . . proved to be higher cognitive development and language-acquisition scores. The mothers who responded to their infants’ cries inconsistently were found to have lower self-esteem and lack of social supports.9

9 Ibid.

Researchers have found that mothers who are depressed have difficulty picking up on a baby’s facial or body signals and are out of synchrony with their babies.6 When a baby’s frustrated attempts to engage his mother are not responded to, he will eventually stop trying to communicate his needs to her. This can affect his brain development, lower his IQ, and put him at risk of becoming depressed as well.7 Researchers have also found that when mothers respond quickly and appropriately to their babies’ cues over time, these children develop better language, cognitive abilities, and self-esteem.8

6 Isabella and Belsky, “Interactional synchrony and the origins of infant-mother attachment.”

7 Kendall-Tackett, The Hidden Feelings of Motherhood, 25.

8 Lester et al., “Developmental outcome as a function of the goodness of fit.”

Many societal challenges can interfere with a parent’s ability to develop a responsive relationship with his or her baby. For example, parents may believe myths about spoiling a baby, or they may follow advice (often unsolicited) from well-meaning family, friends, and medical professionals, the media, and self-proclaimed “parenting experts.” More often than not, this advice conflicts with the science of normal child development. The parents’ own intuitive feelings become suppressed, which can undermine their confidence and create unnecessary stress.

In the course of a child’s development, she begins to form attachments with the person who spends the majority of time nurturing and caring for her. Frequent holding throughout the day and playful interactions with your baby will increase bonding and promote a secure attachment. Many new parents are relieved to learn that most babies need a lot of close physical contact.

It is impossible to spoil a baby when satisfying his need to be held. When you listen to your baby, you will find he is most content and happy when being held close to you—this is because he is experiencing life as part of you, not as a separate being. Who doesn’t want a happy, contented baby? Soon enough, your baby will be squirming in your arms to be put down.

In the first six months or so, your baby may seem perfectly happy being held by and interacting with other people. Then, around eight to nine months of age, she may suddenly begin to respond with fear and anxiety to strangers and less familiar family members. Attempts to separate her from Mom will be met with desperate clinging and crying. Rest assured, this is normal developmental behavior, which most babies experience as they develop more awareness of the world around them. It is actually a good sign that she wants to remain close to the person to whom she has become attached. Knowing this should make it easier to cope with, rather than allowing yourself to become overly concerned or frustrated. This is an important phase of development, and the baby’s feelings require that you continue to be sensitive in your responses, to help her feel safe and secure. This is not the time to teach your baby to be independent or to self-soothe. The intense fears of separation will gradually subside as your child matures over the next few years, depending on her temperament. It may take considerably longer to pass for more sensitive children, especially if they have to learn to be comfortable in the care of nonparental adults. Follow your child’s cues rather than forcing her to accept the well-meaning actions of strangers or expecting her to overcome stranger or separation anxiety before she is developmentally ready. This can also be an intense time for Mom; she will need a lot more support and understanding from her family and friends.

There is the language of the embrace, the language of the eyes, the language of the smile, vocal communications of pleasure and distress. It is the essential vocabulary of love before we can speak love.

—Selma Fraiberg,

In Defense of Mothering: Every Child’s Birthright

Responsiveness and Development

Responding sensitively to your baby teaches him that he is loved and that he can trust you to be there for him. In the beginning, infants don’t understand what love is. What they know is that when they feel hungry, uncomfortable, insecure, and frightened, they need someone to respond to them. From a biological perspective, they are born with three basic survival needs: proximity (close physical contact to Mom or the primary caregiver), protection (the need to feel safe and secure), and predictability (knowing that Mom or Dad is consistently available and that their needs will be met).10

10 Concept originated by Isabelle Fox, PhD.

From a neurological perspective, it’s important to understand how responsiveness plays a significant role in brain development. As we discussed in Chapter 1, a baby’s brain is greatly underdeveloped at birth (only 25 percent is developed), making him highly dependent upon his parents for everything, especially food, warmth, and comfort. Brain researchers have found that the mother’s face, emotional expressions, and tone of voice have a direct impact on the development of the brain. The development of critical parts of the brain coincides with the period in which that attachment develops—during the first three years.11

11 Schore, “The experience-dependent maturation of a regulatory system.”

Because of their neurological immaturity, infants cannot be expected to figure things out on their own—to soothe themselves—especially during the early weeks, months, and sometimes years. You are the emotional regulator for your child until her brain growth has caught up and he is developmentally capable of regulating her own feelings. This is a gradual process that happens over the first few years.

When faced with stressful or fearful situations, your baby or young child needs calm, loving, and empathetic parents to speak affectionately and reassuringly to him. Using comforting touch such as holding, massage, or stroking also helps children learn to regulate their emotions and intense feelings. The sucking reflex remains strong for babies and toddlers and goes a long way in helping to comfort them.

Sue Gerhardt, author of Why Love Matters: How Affection Shapes a Baby’s Brain, describes a parents’ role: “Parents are really needed to be a sort of emotion coach. They need to be there and to be tuned in to the baby’s constantly changing states, but they also need to help the baby to the next level.” For instance, she writes that with the help of parents, children will begin to identify specific feelings with words like frustration, irritation, anger, silly, funny, joyful—a wide range of emotions. Parents can do this by “helping the baby to become aware of his own feelings, talking in baby talk, and emphasizing and exaggerating words and gestures so that the baby can realize that this is not mum and dad just expressing themselves, this is them ‘showing me’ my feelings.”12

12 Gerhardt, Why Love Matters, 24–25.

If a child’s need for comfort is not met by an emotionally responsive adult, the child’s nervous system can, over time, remain in a hyperaroused state.13 Uncomforted stress can lead to a host of physical ailments later in life, including eating and digestive disorders, poor sleep, panic attacks, headaches, and chronic fatigue.14 If left to cry alone in childhood and without therapy in later life, the higher-level brain functions that regulate antianxiety chemicals in the brain are impaired. This may result in clinical depression.15

13 Graham et al., “The effects of neonatal stress on brain development.”

14 Field, “The effects of mothers’ physical and emotional unavailability on emotion regulation.”

15 Hariri et al., “Modulating emotional responses.”

Most parents find that caring for their baby is more intense than they expected. A so-called fussy baby is a sensitive baby and can magnify the intensity of your parenting experience. You may find yourself quickly overwhelmed. “High-need” is a term used to describe a certain temperament of baby who is very sensitive and who may experience more periods of fussiness than other babies. Sensitive babies can become overstimulated in a variety of ways, such as by cold air, bright lights, sudden noises or movements, or too many different adults giving her attention.

Sensitive babies tend to be more vocal about what they need, and adults may incorrectly perceive them as too demanding. Instead of perceiving the baby’s “fussiness” as disapproval, try to see it as a signal that he is overwhelmed with his own feelings and needs, and he is seeking help to find his equilibrium. High-need babies may well require more soothing, but in the aftermath of such consistent responsiveness, these children often develop a peace about them that shows they have been deeply nurtured. Margot Sunderland, a child psychotherapist and author of The Science of Parenting, describes the mechanisms that work in a baby’s brain to help him cope with stress later in life: “If you consistently soothe your child’s distress over the years and take any anguished crying seriously, highly effective stress response systems can be established in his brain.”16 So don’t worry that you might be “giving in” by responding to their cries; they often grow up to be delightful, spirited children with strong leadership qualities. In time, as your baby matures and you become more attuned (tuned in), you will know intuitively when he gradually becomes capable of waiting a few minutes for your response.

16 Sunderland, The Science of Parenting, 37.

Cultural expectations have led us to believe that babies should sleep through the night for at least a good six to seven hours. This ongoing myth keeps many parents frustrated and can cause them to become desensitized and less responsive if they feel they are reinforcing a negative behavior, such as waking, fussing, and crying. Researchers have found that infants have different sleep rhythms, with more periods of light sleep, and aren’t naturally designed to sleep for long stretches of time in their early months—especially breastfed babies.

The reality is that your baby still needs to be cared for during the night. Allowing a baby to cry for prolonged periods with the intention of teaching her to sleep on her own causes the baby to experience abnormally high levels of stress hormones (cortisol), creating an unbalanced chemical state in his brain. Researchers have found that responsive mothers help a baby’s stress hormones normalize more quickly.17 Minimizing stress for your baby is important; children who experience high levels of cortisol are at risk for emotional problems later in life.18 More information on responding to a child’s nighttime needs is available in Chapter 6.

17 Albers et al., “Maternal behavior predicts infant cortisol recovery.”

18 Gerhardt, Why Love Matters, 78.

When Baby’s Cries Overwhelm You

Remaining sensitive and empathetic when faced with a crying, inconsolable infant can be very hard for many parents. It calls for awareness and a lot of patience. This doesn’t typically come easily or naturally—especially if you weren’t raised that way. At times, you may find it difficult to be emotionally responsive, especially when you are feeling exhausted or are experiencing a lot of stress in other areas of your life. Hendrix and Hunt write in Giving the Love That Heals, “If you find yourself reacting strongly to your child’s dependence on you, then you may have been wounded at this stage [of development]. You can use this insight to focus your attention on issues that you need to work on in your efforts to become a conscious parent.”19

19 Hendrix and Hunt, Giving the Love That Heals, 201.

Whether you are balancing the needs of a new baby and an older sibling or the demands of being emotionally responsive to a high-needs baby, fatigue, frustration, and exhaustion can cause you to overreact, so don’t take this lightly! Even the best of parents can become dangerously overwhelmed without support and rest. Call in the reserves (Dad, Mom, a friend), and allow yourself some time alone to rest, collect your sense of calm, and practice personal reflection so that you don’t take your baby’s crying personally or fall into the mind-set that the baby is being manipulative.

Symptoms of burnout or inability to cope with baby’s needs are signals that you need extra support or professional help. We discuss this in more depth in Chapter 9.

Musings from a Mother of Multiples

(continued)

There was so much more crying with twins than with a singleton. It simply was not possible to meet their needs the way I could meet the needs of one. I would get horrible guilt if one cried more than the other. It’s awful, but sometimes I would put them both down to do something I could have done holding one because I just couldn’t bear to pick. Other times I would hold one for a few minutes while the other screamed, and then switch. It was gut-wrenching, and I spent a lot of time crying myself. Sometimes I would wear earplugs as I tried to comfort them because the agony of two crying babies rattled me to the core. The earplugs took a little bit of the edge off so I could stay calm and focused on them. Whenever possible, I held them both. That in itself was hard. My back and arms ached. I had to lean backward to adjust my center of gravity, and then I couldn’t see the ground in front of me. I couldn’t cradle both horizontally, so they had to be upright even when they would have preferred another hold. I was terrified I was going to trip and drop them both. I became very strong. I had the muscles of a weight lifter! I just kept telling myself that I could do anything for a year. I would think of the hardships our ancestors endured. It was just one year. I could do it.

The first year was totally about survival. I took things fifteen minutes at a time. I tried to smile and laugh some, but I cried a lot more. It was so hard to feel uniquely bonded to each. Those fun infant moments, where you gaze into a baby’s eyes or stroke his hair while he sleeps, they just didn’t happen. Not often, anyway. The mechanics of holding two meant that I was rarely gazing into their eyes. I remember another mom saying I could surely tell them apart because “I was the mom.” I just cried. I couldn’t tell them apart as well as my husband and daughter could, who often saw them side by side in my arms. Later I would learn about them as unique kids, but in the beginning, they almost felt like one being. I was so overwhelmed by meeting their needs and making sure they could be attached to me as their mom that I didn’t have time to stop and get to know them as my individual sons. It’s hard to describe. I have a singleton now, my fourth child, and only now do I really see how much I missed of that first year. Even little things were overwhelming, like I couldn’t enjoy bathing one because I only had a few brief minutes before the other, waiting in a bouncy chair nearby, would start crying. I couldn’t help one toddler walk unless there was someone else home to help the other. So many things were about timing—just rushing through the motions and moving on to the next baby. Diaper changes were horrid. Every baby wants to be picked up and comforted after a change, but the first boy would have to wait for the second change, and then they had to share my arms. They usually didn’t seem to mind sharing. They would snuggle in to each other, grip on to each other. It was all they had ever known. But I knew. I had a singleton, and I knew how much more each “should” have. It made me sad that I couldn’t give them what I felt they needed. At the time I was sure they would not be properly attached, that I wasn’t doing “good enough.” It was a dark time. But they are older now, happy, and securely attached. My husband likes to remind me that even on my “worst attached” day, our kids get more connection than on some kids’ best days. Kids are resilient, and while I would never advocate testing that resilience unnecessarily, it does seem at some level twins just “know” they are rough on a mom. They forgive a lot. And they have each other. (To be continued)

[Authors’ Note: Children are forgiving and resilient, especially when they know they are loved. We can’t quiet our child’s every cry or heal every hurt, but we can be there for them, to comfort the best we can.]

Remember that infants cry to communicate their needs and feelings. Here is a list of some of the most common reasons babies cry or appear “colicky.” In time, you will develop a mental checklist and go through it quickly as you try to determine how best to help your fussy baby. It is helpful to try different approaches—your baby will let you know when her need is being met. Sometimes the only thing you can do is hold her.

- Hunger

- Fatigue

- Loneliness

- A need to be held

- A need for skin-to-skin contact

- Discomfort, irritability, or gas (also known as “colic”)

- Feeling too hot or too cold

- Perception of the mother’s stress

- Sress from too much stimulation

- Understimulation (needs more loving interactions with parents)

- Surprise from loud, sudden noises

- Food sensitivity to something directly ingested or passed through the mother’s milk

- Unidentified pain or medical problem such as ear infection, gastroesophageal reflux, urinary tract infection, or anemia

Toddlers still need a sensitive and responsive parent as their bond to you continues to grow. You can maintain your responsiveness by using the following tips:

- As your child grows, responding with empathy, respecting your child’s feelings, and trying to understand the need underlying his outward behaviors will help you continue the close connection you nurtured when your child was a baby. Young children continue to need a lot of loving attention. As toddlers begin to demonstrate more independence, parents can support their explorations by providing a safe environment for discovery and staying nearby to respond when the child needs it. By showing interest in their toddlers’ activities, participating in child-directed play, and sharing in their excitement, parents build their children’s confidence and help them develop skills. Throughout the early years, children require frequent feedback from their parents as they try new things.

- Parents are instrumental in helping their children develop social skills. Parents can set up appropriate playdates for their child, monitor the children’s play, and intervene using positive discipline techniques to keep the children safe and teach effective communication techniques and concepts of fair play. While some toddlers are ready for, and do enjoy, more formal preschool environments, it is not necessary for the socialization of young children. When evaluating any program in which parents are not included, consider your child’s readiness to separate from you and the amount and type of support provided by the adults supervising the program.

- Parents are the child’s first teachers and begin teaching from birth. Enrich your child’s experiences on a daily basis as much as possible. Seek out activities that you can do simply that don’t require spending money. Children really love learning and soak up everything like a sponge. Parents who are attuned intuitively help stimulate that learning environment by following their child’s current interests, answering questions, and responding to daily “teachable moments.” You can read, sing, play learning games, create projects, and follow your child’s lead in play. Toddlers are also capable of playing alone or alongside Mom or Dad as they do other chores around the house. Toddlers love to mimic what they see you do, so give them opportunities to perform tasks like folding towels or washing the car. They learn that working can be fun, and it makes them feel like they are a helping member of the family.

Mothers whose behavior toward their preschool children is responsive, nonpunitive, and nonauthoritarian are more likely to have children who exhibit prosocial behavior.20

20 Zahn-Waxler et al., “Child rearing and children’s prosocial initiations.”

Parents bring the baby into this more sophisticated emotional world by identifying feelings and labeling them clearly. Usually this teaching happens quite unself-consciously.21

21 Gerhardt, Why Love Matters, 25.

Responding to Toddler Tantrums and Strong Emotions

You’ve seen it happen: you’re in the grocery store or restaurant and a young child has a meltdown—whining, crying, or maybe screaming on the floor. You may have thought, “That child just needs a good spanking,” but in reality, that child needs a parent who remains calm. It is critical to respond to children’s strong emotions, even when they act out with negative behavior or tantrums. How do you do it? You can start by not taking his behavior personally and by trying to see the world through his eyes, with the understanding that it’s up to you to help your child regulate his emotions. The best prevention is to avoid putting yourself and your child in a situation you know will likely lead to a meltdown, such as shopping when your child is tired or hungry. Plan ahead as much as possible and keep in mind the low tolerance level of children; they can get bored rather quickly.

If you do have to go shopping, talk to your child ahead of time and explain what you’re going to do and what your expectations are for her. Make sure she is fed or you have snacks with you. Try creating a game of shopping by giving your child some item to look for in the store. Keeping their little minds busy (distraction is easy at young ages) will keep them from getting quickly bored and becoming cranky.

Temper tantrums are an outlet for emotions that are too powerful for a young child’s undeveloped brain to manage in a more acceptable way. Tantrums represent real emotions and should be handled empathetically. A parent’s role during a tantrum is to acknowledge and validate the child’s feelings and provide comfort, not to get angry or punish her (even if you feel the urge). Remember that as children grow they develop empathy and improved social skills when you respond with love and affirmation.22

22 Zhou et al., “The relations of parental warmth.”

In the heat of the moment, it is likely that your child will not be able to talk about his feelings or will need your help to give his feelings the right words. He might respond best to soothing words and physical comfort. To calm an upset child, remain composed and try techniques such as distraction, cuddling, or, if it is more comfortable for the child, holding or sitting next to him while talking gently to him (assuming you’re not in the middle of the grocery store). You will likely have to experiment to find out how your child responds best—every child is different, as is the situation. You can learn to model appropriate ways to deal with young, fragile emotions by using empathy and compassion for the child who is tired, frustrated, hurt, or angry. You can read more information about handling tantrums and strong emotions in Chapter 8.

Helping Children Learn to Express Feelings

Children learn empathy from parents who have been responsive to them. Once the child is three, four, or five years old, parents are better able to use language and reason to express empathy; this helps children understand their feelings and the feelings of others. The seeds of empathy are growing during the early years, and you will begin to see the results of your efforts when your child begins to show kindness toward another child or concern for a child who is hurt.

Many parents tend to forget that children, like adults, need to learn how to express their feelings. It’s hard to do without the appropriate words, and many adults are not even literate when it comes to adequately expressing their own needs and feelings. A program called Nonviolent Communication (NVC), also called Compassionate Communication, offers resources to teach adults successful ways of expressing feelings that meet deep emotional needs. (Read more about NVC in Chapter 8, and visit the Center for Nonviolent Communication’s website, www.cnvc.org.) Being sensitively responsive to your baby is the beginning of teaching compassionate communication skills for life.

In the early weeks and months, a father can feel like second fiddle to the mother and baby. They seem to have a nice thing going, but when and where do fathers fit in? According to Dr. William Sears, fathers are often portrayed as well-meaning but bumbling when it comes to caring for newborns. He has found that “fathers have their own unique way of relating to babies, and babies thrive on this difference. . . . Studies on father bonding show that fathers who are given the opportunity and are encouraged to take an active part in caring for their newborns can become just as nurturing as mothers. A father’s nurturing responses may be less automatic and slower to unfold than a mother’s, but fathers are capable of a strong bonding attachment to their infants during the newborn period.”23 Attachment researchers have found that babies are born with a drive to initially form a close emotional bond (attachment) to one person, usually the mother or the primary caregiver. As the baby matures, she is more able to expand her universe to be more inclusive of the father and others in her life.

23 Sears, “Bonding with your newborn.”

Mothers can and should actively promote bonding with fathers. Dads can be great at comforting, burping, bathing, dressing, and diaper changing. In fact, fathers’ unique styles of interacting and playing with the baby should be honored and encouraged. You may find the child begins to prefer Dad for diaper changes or giving a bath. Nestling on Daddy’s chest for comfort or sleep creates a very special bond that is sacred. But when hunger pangs begin or discomfort occurs, your baby will likely cry for the parent to whom she is most attached—usually Mom. Fathers are more likely, but not always, to remain the secondary attachment figure in the child’s life until two to three years of age, or sometimes longer, depending on the temperament of the child. But take heart, this is normal child development. Before long, your child will be begging to go with Dad or do things with him that will create precious lifelong memories for everyone.

The Fatherhood Initiative reports that the degree of father closeness determines the likelihood of adolescents engaging in risky behaviors such as drinking, smoking, and using hard drugs and inhalants. The report states, “Given that father closeness reduces adolescent drug use, and that father closeness is highest in intact families, adolescents in intact families are at the lowest level of risk for engaging in drug use. The level of risk of adolescent drug use increases in blended families, is still higher in single-parent families, and is highest in no-parent families [families in which neither parent is involved, such as a state-run institution]. On measures of smoking, drinking, and the use of inhalants, father closeness has independent, positive, and powerful effects on adolescents. On the other hand, there is no direct correlation between mother closeness and any of the measures of adolescent drug use. In other words, efforts to reduce adolescent drug use must emphasize the strengthening of father-adolescent relationships, regardless of the type of family structure in which the adolescent lives. The strengthening of father-adolescent relationships is especially important for the millions of adolescents living in father-absent homes, where limited contact with nonresident fathers is inadequate.24

24 National Fatherhood Initiative, “Family structure, father closeness, and drug abuse.”

As a culture, we have always had different perceptions and expectations of boys. People often fear that if boys are nurtured too much, it somehow warps their personalities and makes them too dependent and too sensitive. Conventional attitudes about boys permeate all aspects of society (e.g., parents, grandparents, teachers, and coaches) and has created what William Pollack calls a “boy code”—myths that boys’ behavior is driven solely by their hormones and not the environment, boys need to learn to be tough at an early age, and so on. This code has only served to force boys to become disconnected from their feelings—less sensitive and more aggressive.

New research has begun to reverse this trend by emphasizing the importance of mothers and fathers in nurturing strong emotional connections with their sons. For instance, Dr. Pollack found from his research that “the absence of a close relationship with a loving mother puts a boy at a disadvantage in becoming a free, confident, and independent man who likes himself and can take risks, and who can form close and loving attachments with people in his adult life.”25 Research conducted by the Fatherhood Initiative showed that “adolescents who are close to their moms and dads have less of a need to seek out affirming relationships outside of the home, which can lead to risky behavior (gangs, smoking, drinking, and drugs).”26 Eli Newberger, MD, in The Men They Will Become, says, “It is easy to slip into the habit of touching an infant boy mainly when he needs to be fed, cleaned up and changed, or comforted in irritability. . . . Every boy needs a lot of touching given just for the pleasure it will provide; and a parent needs the heartwarming feedback of a happy boy.”27

25 Pollack, Real Boys, 83.

26 National Fatherhood Initiative, “Family structure, father closeness, and drug abuse.”

27 Newberger, The Men They Will Become, 42.

This research points to the protective benefits of nurturing a strong connection with young boys by both mother and father. If you have a family in which the father is not involved, it’s important for your child to develop a loving relationship with a father figure, such as a brother, an uncle, or a grandfather. Your sons may be fathers themselves someday, modeling what they learned from both sexes—the skills to nurture their own children.

How to Be Responsive in Spite of Life’s Challenges

When life throws you some curves, you do the best you can with what you’re given. Some situations may not be ideal for raising your child. If your life situation puts an emotional strain on your relationship with your child, your efforts to maintain sensitivity and responsiveness with your baby will help minimize the negative effects.

Single Parenting

There are no two ways about it, single parenting is really tough! If at all possible, consider moving in with grandparents or other family members to have a built-in support system for parent and child. Another option is for single parents to seek out other single parents to share an apartment or home with, as well as support each other in parenting. It’s critical to be on the same page as far as parenting values and child care for these types of arrangements to work successfully. Single parents may find that cosleeping with their baby after work or school provides a wonderful opportunity to reconnect and be responsive at night. If grandparents or others care for the baby during the day, be sure they know that you want them to be consistently and sensitively responsive to your child, because crying it out is not acceptable.

If you feel alone and isolated, create your own extended family with your network of friends or seek out other single parents in person or online. Find a local API support group or consider starting one with other like-minded families.

Adoption

Adopted infants will bond sooner if the care and responsiveness of the parents is consistent and loving. If an adopted child has a history of trauma, developing trust may take longer, and her needs may be more intense. Regardless, it is critical that the adopted baby learn that her new parents are consistently available and responsive. If adoptive parents find this challenging in any way, then professional help from therapists knowledgeable about adoption and trauma can be a valuable and critical resource. Children who are adopted from foreign countries adjust much more easily if the adoptive parents bring an item from the orphanage that will help make the child feel more secure, like a special blanket or toy. If the child is eating solid foods, continue to provide similar foods until the child becomes adjusted to her new life and new experiences. The following website offers a lot of good information about attachment parenting for the adopted child: www.adoptivefamilies.com. For the Eight Principles of Parenting for the adopted child, go to www

.attachedattheheart.com.

Divorce

Here again, consistency is key. Divorce situations can be very difficult and will vary depending on the parents involved. To prevent breaks in the attachment process, it’s important that both parents commit to open communication, keeping prolonged separations to a minimum, with day and nighttime routines as consistent and as developmentally appropriate as possible. For the children to make a reasonably healthy adjustment to losing the intact family, both parents will have to make their child’s emotional welfare the top priority. In many cases, this means setting aside differences and working together to be active in their child’s life and activities. Most important, both parents need to remain sensitive to their child’s feelings and be responsive to his emotional needs. API’s website contains information regarding visitation and overnights. A strongly recommended book that focuses on maintaining the attachment relationship is Creating Effective Parenting Plans: A Developmental Approach for Lawyers and Divorce Professionals by John Hartson, PhD, and Brenda Payne, PhD. It can be purchased through the American Bar Association website (www.abanet.org). Also recommended is The Unexpected Legacy of Divorce: A 25-Year Landmark Study by Judith Wallerstein, Julia M. Lewis, and Sandra Blakeslee and What About the Kids? Raising Your Children Before, During and After Divorce by Judith Wallerstein.

Children with Special Needs

Children born prematurely, with physical handicaps or challenges, or with other forms of disability are no different from nonchallenged children in their psychological and emotional needs. It’s important to understand that you are the expert about your child and that when you feel connected and tuned-in to what your child needs, you will respond intuitively. Challenged children often spend much of their childhood experiencing a maze of different doctors, hospitals (sometimes multiple surgeries), therapists, and teachers. As a result, it’s critical that parents establish a strong bond with their child because it will strengthen their ability to be fierce advocates for him, and that bond will give their child the love, support, and courage he will need. You can find additional resources about this topic and others in Appendix C. Also, visit our parent forums on this and other topics at www.attachmentparenting.org/forums/.

Having More Than One Child, Twins, and Other Multiple Births

If you’ve had your first baby, you may now wonder, “How will I be able to parent the next one with the same devotion, care, and empathy? Won’t the older child suffer when a new baby takes her place? How should I space my children for optimum attachment? What about birthing twins, triplets, or other multiples? Is it possible to practice the attachment parenting principles when there are so many needs to fulfill?” These are common questions for all parents, no matter what philosophical view they may have about parenting.

Most of us will have one baby at a time, and spacing our children is a definite consideration when thinking about the attachment needs of each child. Many child development experts feel that at least two and a half to three years between children is beneficial, because the older child has the language and cognitive skills to understand the needs of an infant and can more easily delay his needs than a younger child. The older child may have less jealousy and be able to help in some ways, like bringing diapers or sitting with books and toys while the baby is being fed. Having babies really close together is almost like parenting twins, because they will have similar needs and will probably be in fairly close developmental stages. We advise parents of closely spaced babies to get a lot of help and support, just as if they had given birth to multiples, because the older child will probably not want to be separated from Mom for very long. This is especially true if he is still nursing or is too young to understand where Mom has gone. He only knows that he needs his mother, and Mother needs to be supported in parenting both babies.

We are always amazed to hear the stories of parents who have successfully parented multiples—their stories inspire the rest of us with singletons, and we can learn a lot from their experiences. Organization, prioritizing, and support are the key components to keeping balance in the family. One mother of triplets (and an older child) we worked with said that if it weren’t for the volunteers from her church, she never would have been able to successfully breastfeed her babies. She was able to pump enough milk so that while she was nursing two, the third baby could get a bottle if needed, and by the time they were a few months old, she was able to nurse them all without bottles. Volunteers did her laundry, took her older son for outings and preschool, and brought her family meals. When Mom and Dad can focus on the children and their needs, and the community helps support the parents, everyone can keep their sanity, their sense of humor, and their stamina! Best of all, the attachment needs of each child can be met, and parents find that somehow they do have the ability to give tremendous stores of love to each child they are blessed to parent.

Musings from a Mother of Multiples and an Older Sibling

(continued)

Things were so much easier at home. I think if I hadn’t had an older daughter, I would not have left the house for the first year. I had to go out because she needed to have a “normal” life. It felt so much like I was depriving her. Between my bedrest during the pregnancy, the NICU weeks, and the first several months at home when I just couldn’t manage to leave the couch, let alone the house, she lost nearly half a year of her normal activities. When the boys were a few months old, I felt I had to leave the house for her. It was overwhelming to get anywhere. The amount of things I needed to carry with me was crazy. I received a huge Skip Hop Duo Diaper Bag, and it was fabulous. Now with a singleton, I can’t imagine how I ever filled it up! I learned to go places where there would be other moms who could help me. When I saw the same moms frequently, my boys got to know them and were happier in their arms. I worried a lot about my daughter in the first year. Books on new siblings talk about sitting with the baby on one side and the sibling on the other, sharing things together. That was impossible. She had been completely displaced; there was no place for her on my lap. I included her as much as I humanly could, but it never felt like enough. Some people told me I should send her off to school, but I knew that then there would be even fewer shared moments. It really was just a matter of surviving the first year. Things got a little better with every milestone . . . with neck control, with sitting, with walking . . . the older they got, the more she could be involved and the more we felt like a family again. (To be continued)

—Pam S., mother of four

Within hours of my firstborn child’s birth, I got the distinct sense that he wanted a fourth trimester. Here I was, full of breathless anticipation, unspeakable bliss, and mortal terror, and there he was looking at me square in the eye, as if to say, “Work with me, Ma.”

I had prepared as so many mothers do for their first baby. But I could have never known the profound effect of meeting someone else’s needs because I never took the time to know what they were in the first place.

My son was poised to show me the difference between unmet needs and fulfilled ones, from the time he was a newborn to today, nearly ten years later, as a boy embracing his emerging self-reliance.

They called him a “high-need” baby. What did that mean? Aren’t we all high-need humans? I thought. They called him “fussy.” Isn’t that a judgment of him? I reasoned. And in calling our babies names—fussy, demanding, good, easy—wouldn’t this usher in our fears, fueling our defenses? How could I love my baby unconditionally, I wondered, if part of me was afraid of him? And wouldn’t he sense that subtle rejection somehow?

As with any burgeoning conviction, I was tested. In those early months, he was averse to the car, the bath, clothes, diaper changes, the telephone ringing, lights, appliances, distant lawn mowers outside his window, being rocked back and forth as opposed to side to side, and the sound of his Velcro diaper tab being pulled ten times a day. Friends, relatives, our pediatrician, and perfect strangers told me to “put him down or he’ll think the world revolves around him.” What they (and we) didn’t know was that the world actually was revolving around him—he had vertigo.

We didn’t discover this until he was five and could finally tell us. During those five years, we followed his lead. The road to uncovering and defining his complex sensory sensitivities was, at times, confusing and circuitous. Along the way, we had to find out what drives him, what motivates his reactions, what stirs him and soothes him in order to begin to know him in tiny increments every day. This, I thought intellectually, was the easy part. After all, as his mother, I loved the minutiae of his existence, reveled in his perfect beauty, even as I stared with drunken love at his crossed eyes and pimply face a mere four weeks after our first glimpse of each other. I was prepared to love him with all my heart. What blindsided me was my fear.

He cried inconsolably, and I felt my own helplessness. He wailed, and I felt his disapproval. He couldn’t sleep, and I felt forsaken and fragile. As he grew, I spent more than a few nights blinking in the darkness, wondering if I had chosen the right school or teacher or therapy or doctor or response.

It was all about me. And yet, it was not about me at all. It hit me. How could I respond to him with sensitivity, taking his needs and feelings seriously, without taking them personally? How could I get out of the way enough to parent in the moment, allowing him—and me—to flourish as mother and child, so that both of us are organically changed in the process?

I realized, in those moments, that intuitive, conscious, attached parenting requires something that none of us learns on the playground, in the classroom, or on the job: grace. The only way I got a taste of its delicacy was through my own painful rites of passage. Those times, as a mother, when I’ve had the whistle blown on my own pretense and defense. I now know that a baby is wise and forthright enough to smoke a parent out of her hiding places. The same goes for that same baby standing tall enough to reach my collarbone when he hugs me.

I need my maternal radar more now than I ever did. He needs me to move away—closer. His space is sacred. And yet, he needs to share that space. He needs my sensitivity to his changing moods, perceived overreactions, and quirky preferences. But more than my understanding, he needs my authentic presence. Responding to him is no longer about meeting basic needs, but about recognizing individual, deeply personal ones—and respecting them, in spite of my fear. I have learned to respond to what’s invisible. Because I want to see him with my heart, not my eyes.

—Lu Hanessian,

Let the Baby Drive