Charting a New Course: Breaking the Ties That Bind

Nothing is more important in the world today than the nurturing that children receive in the first three years of life, for it is in these earliest years that the capacities for trust, empathy, and affection originate.

—Elliot Barker, MD,

The Critical Importance of Mothering

This quote by Dr. Barker, a long-time mentor of ours, a forensic psychiatrist, and the founder of the Canadian Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (CSPCC), eloquently expresses the profound importance of nurturing our young, yet it receives little importance or emphasis in our society. In fact, a nurturing parent—one who devotes time and attention to a baby or young child—is more likely to draw criticism from the public and media than praise.

We felt it important that parents see the “big picture,” to understand why we wrote the book and how parenting attitudes and child treatment directly affect families, communities, and generations to come. It has been clear for some time that there is much we can do as a society to prevent mental illness and intergenerational violence, beginning with parent education and creating community support for families, yet violence against children continues to rise.

The statistics of violence against children in the United States are staggering: Every day 5 children die from child abuse (a rise from 3.13 deaths every day in 1998), and it’s estimated that 50 to 60 percent of child deaths from abuse are not documented correctly. Every year there are 3.3 million reports of child abuse involving more than 6 million children. Thirty percent of abused children become abusers as adults; 80 percent will develop at least one psychological disorder.1

1 See Child Trends, www.childtrends.org/pages/statistics.

As you read our book you will realize that much of what we write about or recommend is counter to popular societal beliefs. If you understand why you are consciously making certain choices and that they are supported by science, it will help build your confidence. Being confident in your decisions and choices will go a long way in deflecting criticism from well-meaning family, friends, and even doctors. Appendix A can help you deal with some of the myths people have about attachment parenting.

Because many of us have little or no experience with babies or children, it is difficult to know what to expect when we become parents. Maybe you have read a few books here and there, but without prior experience there’s no way of really understanding the day-to-day reality. Most people don’t think to discuss the kind of parents they want to be with their partners before having children, nor do they discuss the kind of adults they want their children to become. For many parents, the first baby they ever hold is their own. As important a role as parenting is for the future of families and society, there are no minimum requirements for education or standards of care. Many experts believe some form of child development and parent education should become a requirement in schools. Too often we spend more time and energy researching the details for buying a house or a car than we do for raising children, probably because we feel we will just learn on the job. Imagine you are about to climb the world’s highest mountain. You would have two choices: you could begin your journey on your own and figure it out as you go (more difficult and reducing your chances for a successful climb) or you could prepare yourself physically, mentally, and spiritually, and your chances of achieving your goal would be much higher. Without a little knowledge and experience, we default to parenting the way we were parented, and for some families that may be fine, but for many families there is a lot that can be improved upon. The last twenty years have given us a wealth of research about what makes babies and young children tick. We know what children need from the adults in their lives to reach their best potential, and it doesn’t require that we become perfect parents. Strangely, we begin this incredible, lifelong journey that radically changes us as adults, and most definitely has a lasting effect on our children (not to mention society as a whole), without any experience and very little knowledge.

You know you are face-to-face with the unfinished business of your own childhood when you respond with strong negative feelings to your child’s behavior. . . . Disproportionate levels of fear, sadness, anger, or, conversely, elation or relief are signals to the parent that he has just activated an old wound and might do well to investigate further.

—Harville Hendrix, PhD, and Helen Hunt, PhD,

Giving the Love That Heals: A Guide for Parents

The most natural thing parents can do is to raise their children the way they were raised. You are less likely to be troubled by conflicting advice if you had nurturing childhood experiences. Adults who had diffcult childhoods for any reason—trauma, abuse, neglect, or separation because of divorce, for example—may have some challenges to overcome.

You Can’t Give What You Don’t Have

For some families, implementing attachment-parenting practices just seems natural, like it’s the right thing to do. However, many parents find it diffcult to give emotionally of themselves, especially if they didn’t receive love and nurturing as a child. All those memories that were thought to be buried may resurface when you become a parent. Children’s behavior at certain ages can trigger old wounds or “buttons.” When children “push your buttons,” it’s usually because those buttons were installed a long time ago. You may have thought you had them under control—until you find yourself becoming angry, overreacting, or becoming irrational. These buttons, or unresolved issues, are what some call our “ghosts” from childhood. Our early childhood experiences create powerful forces that are extremely diffcult to overcome on our own and will often require professional help. The first step toward healing is becoming aware—a person has to be conscious and aware of the past in order to not repeat it. For those parents who desire to break the cycle of abuse, becoming a parent can be the impetus for change.

It isn’t necessarily just overt abuse or neglect that is damaging. Culturally accepted parenting practices can also be abusive or neglectful. These practices have deep roots that go back hundreds of years and have become traditional and are now being recognized by some as “normative abuse.”2 In most cases, parents cared for their children the way they were told to by the parenting experts of their day.

2 Walant, Creating the Capacity for Attachment, 8.

“The prospect of having a baby brings forth memories of their own childhood and causes them to reflect on the parenting that they received.”3

3 Fonagy et al., “Maternal representations of attachment during pregnancy.”

They were simply doing the best they could with what they knew. Similarly, now that we know better, we must try to do better for our children.

Beginning the process of raising awareness starts with understanding how so many of us got to the point of trying to overcome our past. Until the evolution of our modern Western culture, children had to grow up fast and get to work, usually on the family farm. By the time they were eight, nine, or ten years old, their childhoods were over.

The period we call adolescence is a stage of development rather newly identified by child development researchers. With the identification of this new stage of development, coupled with new laws earlier in the twentieth century to protect children from abusive work practices, children were allowed to enjoy a longer childhood. All along the way, attitudes about children and parenting practices were largely influenced by strict religious dogma or experts in the fields of psychology and human development—such as Sigmund Freud, L. Emmett Holt, and the “father” of behaviorism, John Watson. Their parenting advice had negative and devastating effects on children and their families—sometimes for generations—ranging from sexualizing children to treating them as objects.

Over the years, thousands of parenting books have been written, each claiming to have the answer to raising good, obedient children, leaving many children feeling disconnected from their confused, anxious, or guilt-ridden parents. For hundreds of years, the treatment of children in many cultures has been harsh and disturbing. We know that the residuals of some of those abusive practices are still present today. While great strides have been made, we still have a long way to go. One classic example comes from the work of psychologist John B. Watson, who admonished parents not to hug, coddle, or kiss their infants and young children in order to train them to develop good habits early on. In 1928, Watson published his widely popular child-care book called Psychological Care of Infant and Child. In it, he said parents should:

Treat them [children] as though they were young adults. Dress them; bathe them with care and circumspection. Let your behavior always be objective and kindly firm. Never hug and kiss them, never let them sit on your lap. If you must, kiss them once on the forehead when they say goodnight. Shake hands with them in the morning. Give them a pat on the head if they have made an extraordinary good job of a difficult task.4

4 Watson, Psychological Care of Infant and Child, 81–82.

In her book Breaking the Silence, actress and comedian Mariette Hartley writes about the heartbreaking legacy for her family and millions of other families created by the advice of her maternal grandfather, John Watson, or “Big John,” as she called him:

In Big John’s ideal world, children were to be taken from their mothers during their third or fourth week: if not, attachments were bound to develop. He claimed that the reason mothers indulged in baby-loving was sexual. Otherwise, why would they kiss their children on the lips? He railed against mothers whose excessive affection made the child forever dependent and emotionally unstable. Children should never be kissed, hugged, or allowed to sit on their laps.

“My mother’s upbringing was purely intellectual. The only time my mother was ‘kissed on the forehead’ was when she was about twelve and Big John went to war. Although she was reading the newspaper by the time she was two, there was never any touching, not any at all. Grandfather’s theories infected my mother’s life, my life, and the lives of millions. How do you break a legacy? How do you keep from passing a debilitating inheritance down, generation to generation, like a genetic flaw?”5

5 Hartley, Breaking the Silence, 18.

Suicide and depression, the legacy left her by her family, resulted in her losing her father, an uncle, a cousin, and almost her mother. Not without her own emotional “demons,” Mariette Hartley was able to break the chain through therapy and raising her awareness about life, love, and spirit. She became a loving mother of two children and continues to work as a successful actress while donating her time to suicide prevention.

New parents’ own early childhood experiences have a major impact on their parenting attitudes and beliefs with the possibility of affecting the attachment process with their newborn child.6

6 Fonagy, “Maternal representations of attachment during pregnancy.”

When “Normal” Child Rearing Crosses the Line

Watson’s legacy, like others’, continues to permeate our cultural psyche in many ways—how we view children, how we speak to them, and how we treat them. To discipline children, our culture has accepted numerous ways of keeping kids in line. They are often talked down to or spoken to harshly, hit, humiliated, shamed, ignored, and, in some extreme cases, tortured—such as by placing hot sauce on a child’s tongue or forcing a child to stand for long periods with his or her arms straight out. A nurse and lactation consultant at a local hospital recently shared this example:

I went into a mother’s hospital room to help her with breast-feeding, and I saw her three-year-old daughter with her back to the wall with her arms straight out in front of her. I asked the mother if her child was playing a game, but she said, “No, she’s being punished for misbehaving. She has to stand there for five minutes.” It struck me that the mother thought there was absolutely nothing wrong with how she was disciplining her child.

These abusive forms of discipline have been so much a part of our culture that we sometimes don’t think twice about them. We have learned to desensitize ourselves to the actual physical and emotional pain that is inflicted on children. After all, that’s how we were raised, and we turned out okay—right? Maybe we were lucky and turned out well in spite of how we were treated; maybe we still suffer in ways we don’t realize are connected to our early childhood years. Some of us were lucky enough to have strong, loving families with parents who did the best they could with what they knew then. We can understand that, embrace it, and even forgive because we know that there are no perfect parents, and their love far outweighs anything else.

Child abuse is a huge epidemic in the United States. Every day, five children die from abuse (up from three in 1998), and, of these, 80 percent are under the age of four.7 We tend to think it only happens in families in poverty, but child abuse crosses all social, educational, and economic barriers and ranges from benign neglect to physical abuse.8 If we are serious about breaking the cycle of abuse, we have to begin in the family. The Child Welfare Information Gateway website lists “nurturing and attachment” as one of the primary factors in preventing child abuse.9

7 Childhelp, “National child abuse statistics.”

8 Child Welfare Information Gateway, “Child abuse and neglect fatalities.”

9 Child Welfare Information Gateway, “Protective factors for promoting healthy families.”

Research has found six important protective factors for families and their children to reduce the risk of child abuse and neglect:

1. Nurturing and attachment

2. Knowledge of parenting and of child and youth development

3. Parental resilience

4. Social connections

5. Concrete supports for parents10

6. Social and emotional competence of children

10 Child Welfare Information Gateway, “Promoting healthy families in your community.”

A growing number of therapists are determined to bring attention to the dangers of “normal” or traditional parenting. In her book Creating the Capacity for Attachment, Dr. Karen Walant first described this type of treatment as “normative abuse”:

Our culture allows for a certain threshold of parenting practices that I term normative abuse. Normative, because these are included in some of the basic tenets of child-raising that are endorsed by the culture in which we live. Normative, because, like the generations before that believed “a child should be seen and not heard,” these are parts of current parenting philosophy. Normative, because these are often tiny moments in a child’s life, moments that may be followed by a loving interaction or a sweet caress. Normative abuse occurs when the attachment needs of the child are sacrificed for the cultural norms of separation and individuation. Normative abuse occurs when parental instinct and empathy are replaced by cultural norms.11

11 Walant, Creating the Capacity for Attachment, 8.

The word abuse is defined as “treating a living creature, whether animal or human, in a harmful, injurious, or offensive way.”12 Dr. Walant acknowledges that even though normative abuse in and of itself may not be as traumatizing as verbal, physical, or sexual abuse, it still has its damaging effects on the overall healthy development of the child.13 Often we don’t realize that damage is being done because we cannot see it.

12 Dictionary.com, “Abuse.”

13 Walant, Creating the Capacity for Attachment, 9.

Yelling, spanking, jerking, slapping, shaming, and humiliating are all ways that we can harm a child’s dignity and our emotional connection. (Read more about the effects of physical punishment in Chapter 8.) You may know parents who are firm in their belief about the use of corporal punishment and crying-it-out methods as forms of discipline. Our goal is not to be judgmental or make this an indictment against parents who hold these beliefs. We’ve done some of the same things with our own children out of lack of knowledge and understanding. Our intent in writing this book is to raise awareness. Only when a person’s awareness is raised can he or she begin to make conscious changes in behavior. So how do we get there from here?

When we spoil something, we deny it the conditions it requires. . . . The real spoiling of children is not in the indulging of demands or the giving of gifts, but in the ignoring of their genuine needs.

—Gordon Neufeld, PhD, and Gabor Maté, MD, Hold On to Your Kids

Understanding Bonding and Attachment

Scientists haven’t always been aware of attachment in humans but have long recognized the bonding that occurs in other mammals right after birth. You may have watched a family dog or cat have babies and noticed how the mother instinctively knew what to do—licking, cuddling, nursing, and protecting. You may have also observed that the babies had their own way of telling the mother what they needed—squeaking, crawling to get closer to the mother, searching for the nearest nipple to suck. Once satisfied, they become perfectly calm and content. Over time, as the babies grew, you may have noticed a special bond deepen throughout their development; the mother most likely became very protective and caring while the offspring began to explore and test their new skills, working toward their independence.

That special bond is called attachment, and it is a process that continues for a much longer time in human babies, usually for the first three to five years of life. It takes so long because only 25 percent of the brains of human infants are developed at birth, which means they will, in a very real sense, continue their gestation outside the womb, much like a baby kangaroo. Kangaroos are extremely dependent upon the mother for a much longer time than other mammals. Even chimpanzees, our closest genetic relatives, who are born with 75 percent of their brains developed at birth, remain very close to their mothers for several years.

Only in the last sixty years or so have professionals in the fields of psychology, anthropology, child development, and social work begun to recognize and accept how vital this process is in determining who we become. We are learning that attachment is at the core of our humanity.

In the ideal home environment, babies flourish; their cognitive, emotional, and physical needs are being met by loving parents as they experience trust, empathy, and affection. They are stimulated and eager to learn new skills. During the first three years, under these conditions, their brains grow at the fastest rate of their lives—millions of cells waiting for “marching orders” before the brain starts pruning back unused cells. Brain cells designed for language and vision, if not stimulated by the environment by the age of six or seven, disappear forever. Children who are not spoken to, for whom language is not modeled, will lose the ability to speak, as scientists have learned from observing feral (wild) children and children neglected in orphanages. The brain is a “use it or lose it” organ, but it’s also highly adaptable to even the most adverse environmental conditions.

The “use it or lose it” principle also applies to learning empathy, affection, and other positive aspects of social interactions and relationships. Brain researchers have found that a baby receives all kinds of sensory information from its mother’s face and tone of voice, which is simultaneously associated with the physical sensations the baby is experiencing. If children do not receive love, affection, and responsiveness from their parents (or primary caregivers), or if they experience significant trauma and abuse, they may never learn what it means to love, to be affectionate, or to have empathy for another human being. All the while, their brains are adapting to their experiences (hardwiring), internalizing what their parents have modeled for them, making it more diffcult to change as they grow older.

What is most striking is that neuroscientists have found that the critical period for the development of certain parts of the brain coincides precisely with the critical period for attachment development—during the first three years of life.14 One such part is the orbitofrontal cortex, located above the eyes in the forehead area between the left and right hemispheres. Dr. Allan Schore from the Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences at the UCLA School of Medicine has described the orbitofrontal cortex as the key component to infant attachment and emotional regulation and believes that it plays a central role in the development of empathy and emotional memory.15 The neurons located in this area are particularly sensitive to the emotional expressions of the human face. Schore believes that the effects of the attachment relationship and the process of mother-infant attunement have a direct impact on the development of the orbitofrontal cortex.16

14 Karr-Morse and Wiley, Ghosts from the Nursery, 37.

15 Siegel, The Developing Mind, 140–41.

16 Schore, “The experience-dependent maturation of a regulatory system.”

Not only is the brain affected by the child’s environment, but so is his or her genetic code. There is an exciting new area of study called epigenetics, which literally means “over or above” genetics. In other words, scientists are looking at other outside factors that influence gene expression or modifications without actually changing the DNA sequence, such as environment. In The Relationship Code, psychologist David Reiss and his colleagues at George Washington University describe the results of their twelve-year genetic study of parenting influences on genetic traits: “Many genetic factors, powerful as they may be in psychological development, exert their influence only through the good offices of the family; we’ll be changing a genetic trait by changing the family environment.”17 In other words, “How parents treat a child can shape which of his genes turn on.”18

17 Reiss et al., The Relationship Code, 49.

18 Begley, “The nature of nurturing.”

For more than eighty years, scientists have been trying to figure out the mechanisms of what turns genes on and off, trying to answer the puzzling question of how humans are able to share essentially the same genetic code as all living things yet be so radically different: “How can the same DNA sequence lead to different outcomes?” And more important, “Why should we care?” Epigenetics has shown that something as simple as what a mother eats while pregnant can change the epigenetic state of her unborn child, and what a mother does with her infant during the first few months of life can affect her child later in life and even the attributes of her grandchildren. In a lab experiment, researchers fed two genetically identical mother rats a different diet. Their offspring were also genetically identical but looked completely different simply because of their mothers’ diets; one was obese and had red fur, and the other was normal size with brown fur. The implications of this research mean that we all have the ability to make changes in our lives, our immediate families, and future generations. It also means, thankfully, that our genetic predispositions are not our destiny. Most stunning of all is that genetic scientists have found that only 1.5 percent of our genes contain genetic code. They have no clue what the other 98.5 percent of our genes actually do, but some hypothesize that humans complete their genetic coding after birth. Our genes become coded by our experiences through our environment. Lynne McTaggart, a science writer, wrote in her book The Bond, “Genes get turned on, turned off, or modified by our life circumstances and environment: what we eat, who we surround ourselves with and how we lead our lives.”19 Now that’s an overwhelming but exciting thought, and this places a huge responsibility on each of us.

19 McTaggart, The Bond, 24.

New research in the fields of neuroscience, genetics, child development, and psychology continues to provide evidence that there is a lot at stake for children and society. This is where the theory of attachment provides the glue that holds all the elements of child development together.

Just as children are absolutely dependent on their parents for sustenance, so in all but the most primitive of communities are parents, especially their mothers, dependent on a greater society for economic

provision. If a community values its children, it must cherish their parents.

—John Bowlby, MD,

Maternal Care and Mental Health

The Legacy of John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth

Two historical figures are largely responsible for our current understanding of children and what drives human relationships. In the late 1930s and 1940s, it was common for children to be admitted into hospitals without visitations by their mothers or fathers for long periods. It was the highest priority that hospitals remain germ-free, so parents were only allowed to visit once a week. Nurses were in charge of the physical care of infants and young children, but they didn’t have time to hold or coddle the children because they had to keep up with their rigid schedules. As a result, the children’s emotional states began to deteriorate quickly. They became sad, depressed, fearful, and unresponsive. James Robertson, a concerned individual in London, filmed this process and then shared the film with a British psychiatrist named John Bowlby. These films so disturbed and intrigued Dr. Bowlby that they led to his life’s work of advocating for children and parents. Bowlby is considered the founder or father of attachment theory. It was his study of young delinquent boys that led him to understand the links between prolonged early separation from the mother (or primary caregiver) and later “affectionless character.” His work was so radical that he was ostracized by fellow psychiatrists, who refused to believe that the environment had anything to do with how children turned out. Rather, they believed it was their genetic makeup.

Throughout it all, Bowlby never wavered in his convictions and maintained his position with confidence and dignity. Still, he had no way of actually proving his theory until Mary Ainsworth came into his life.

Dr. Mary Ainsworth, who was originally from Ohio and educated at the University of Toronto, accompanied her husband to England, where she began working for Bowlby as a research assistant. She later went to Uganda to study the weaning practices of mothers and realized that she was witnessing the natural process of attachment (bonding) of babies and mothers. Ainsworth used this knowledge to develop a procedure, called the “Strange Situation,” to assess the quality of the child’s attachment to the mother. Thousands of research studies later, this instrument is still being used today and continues to validate Bowlby’s early conclusions.

Researchers have learned that the attachment process is a reciprocal one. In other words, both parent and child take turns initiating cues (signals) and responses—baby smiles, mother smiles back; baby cries, father picks baby up to comfort; baby signals he or she is hungry, parent responds by feeding; baby gazes at father, father gazes back, responding with loving interactions. All of these seemingly mundane daily activities are the basic elements of creating a secure attachment. It is not only the bond that the child feels toward the parent, but the bond that the parent feels toward the child. Bowlby and Ainsworth learned from studies done in Uganda and in the United States that attachment relationships fit fairly clearly into three categories: secure attachments, insecure-ambivalent attachments, and insecure-avoidant attachments.20

20 Ainsworth et al., Patterns of Attachment, 347–62.

The Strange Situation procedure performed by Bowlby and Ainsworth was implemented by placing a baby with a stranger in a strange location (the research lab), then having the mother leave for a brief period. This allowed them to demonstrate that babies behaved in different ways depending on their relationships with their parents. The intent was to stress the baby for only a minute or two and then observe how it reacted to the mother leaving and when she returned.

The keys to the procedure are (1) to record how confidently and effectively the baby is able to separate from the mother and resume play and exploration of the toys, and (2) to record the mother’s ability to soothe the baby on reunion. It is the detail of the reunion with the mother that is the key to assessing the quality of the baby’s attachment to her—secure or insecure. Securely attached babies are likely to cry and protest strongly and quickly (other researchers believe that temperament and sex also play a role in their reactions). The babies become extremely upset, but when the mother returns (within a minute or so), they are quickly quieted and resume playing. Ainsworth noted that these children were the most nurtured at home as well.21 It is an amazing process to watch, knowing that every action and reaction tells a part of the story.

21 Karen, Becoming Attached, 147–63.

The findings during the test by no means reflect that the parent-child relationship will always remain secure or insecure, since home environments are always subject to change, but it gives a good indication of the parent-child relationship at the time of the assessment and what could be a continuing pattern of interactions.

The three categories of attachment that Bowlby and Ainsworth created based on their observations are described here. Within each category, there can be varying degrees of attachment.

1. Secure Attachment. The infant actively explores, gets upset when mother leaves, is happy upon reunion, and seeks physical contact with mother. Mothers of secure babies are typically loving and responsive to their infants, are quick to pick them up when they cry, and hold them longer and “with more apparent pleasure.”22

22 Ainsworth et al., Patterns of Attachment, 347–62.

2. Insecure-Ambivalent (Anxious or Resistant) Attachment. The infant stays close to mother, explores to a limited extent, becomes very distressed upon separation, and is ambivalent toward mother upon reunion but remains near her. Mothers of anxious babies were observed to be “more mean-spirited to merely cool, from chaotic to pleasantly incompetent. Though well-meaning, these mothers have diffculty responding to their babies in a loving, attuned, consistent way.”23

23 Karen, Becoming Attached, 159; Ainsworth et al., Patterns of Attachment, 347–62.

3. Insecure-Avoidant Attachment. These infants show little distress when separated, ignore the mother’s attempts to interact, and are often sociable with strangers or may ignore them as they ignore their mother. These mothers often have an aversion to physical contact themselves and speak sarcastically to their babies.24

24 Karen, Becoming Attached, 159; Ainsworth et al., Patterns of Attachment, 347–62.

A fourth category was added years later by Dr. Mary Main and her colleagues:

4. Insecure-Disorganized or Disoriented. These infants are the most distressed upon separation and are considered the most insecure. They seem confused upon reunion or would “act dazed or freeze”; they might “move closer but then abruptly move away as the mother draws near,” exhibiting behaviors that appear to be a combination of resistant and avoidant.25

25 Karen, Becoming Attached, 159; Ainsworth et al., Patterns of Attachment, 347–62.

“The self-organization of the developing brain occurs in the context of a relationship with another self, another brain. This relational context can be growth-facilitating or growth-inhibiting, and so it imprints into the developing right brain either a resilience against or a vulnerability to later forming psychiatric disorders.”26

26 Schore, “The experience-dependent maturation of a regulatory system.”

Attachment: An Idea Whose Time Had Come

Ironically, during the time Bowlby and Ainsworth were researching attachment theory, similar observations were being made in other parts of the world by professionals ranging from psychiatrists to anthropologists. Studying the dominant parenting practices of cultures around the world has given researchers deeper insights into why some societies are aggressive and others nonaggressive. In his book Learning Non-Aggression, anthropologist and human developmentalist Ashley Montagu answers the question of why aggression and violence are totally nonexistent in some nonliterate cultures:

Years ago Margaret Mead was the first anthropologist to inquire into the origins of aggressiveness in non-literate societies. . . . [S]he pointed to the existence of a strong association between child-rearing practices and later personality development. The child who received a great deal of attention, whose every need was promptly met, as among the New Guinea Mountain Arapesh, became a gentle, cooperative, unaggressive adult. On the other hand, the child who received perfunctory, intermittent attention, as among the New Guinea Mundugomor, became a selfish, uncooperative, aggressive adult.27

27 Montagu, Learning Non-Aggression, 7.

Fully recognizing that there are no perfect cultures, through the years we have collected stories from around the world that have indirectly illustrated and validated attachment parenting principles. One of these stories takes place at the end of World War II, when a navy psychiatrist named James Clark Moloney was stationed in Okinawa. He and another doctor were told to be prepared for the devastation they would see—horrible bombings had forced thousands of people to flee to caves and the wilderness areas, exposing them to starvation, life-threatening injuries, and illness. They were told to expect that the psychological impact would be just as horrific, but, to their amazement, they found that the people were, for the most part, psychologically healthy. As Dr. Moloney started investigating why the Okinawan people had survived so amazingly well, he found that before the war they had no psychological wards in their hospitals, and there had only been one murder in their largest city in the last seventy-five years.

Dr. Moloney felt that a key component to the mental health of the Okinawans was how they parented their children. In contrast to the West, where bottle-feeding was quickly becoming the norm, Okinawan mothers breastfed, not only to nourish their babies, but also to give comfort. He noticed how the mothers would carry their babies on their backs in beautiful fabric carriers and let them nurse whenever they needed—not on a strict schedule. Most babies were nursed until at least two years of age or older, and, if the babies were not with the mother, they were carried by another family member—always in contact with someone they knew and trusted. Moloney was also impressed by the respect the adults showed for the children—for example, once when he was photographing a young child, he asked the father for permission to film. The father requested that he ask the child’s permission—a revelation for this American doctor! Moloney reported that he never saw the use of physical discipline like spanking and referred to the Okinawans as “permissive” compared to standards in the United States. They talked to their children rather than using physical force, threats, or coercion. In spite of the fact that the parents were so “permissive,” the children were very well-behaved and rarely cried. He became convinced that their style of parenting was the key to world peace.

Dr. Moloney traveled the countryside for many months, interviewing and documenting his findings in a film called The Okinawan. With great enthusiasm and hope, he took this documentary back to the United States and showed it to standing-room-only audiences in medical schools all over the country. Although these new concepts were fascinating, they were initially rejected with vehement opposition by most in the medical community, even though many of their ideas were put into practice years later. A small group of supportive doctors at Wayne State University formed a group called the Cornelian Corner, and became one of the first groups of mental health professionals to support his conclusions.28 These new and foreign ideas, such as rooming-in, natural childbirth, and breastfeeding on demand, had begun to take hold in the late 1940s and early 1950s in a few experimental hospitals, with good success.29 The Cornelian Corner began its own parenting classes, teaching a select number of American mothers the Okinawan style of parenting, including the idea of wearing their babies. An account of Dr. Moloney’s experiences was written in an article published in the November 1949 issue of Better Homes and Gardens magazine, entitled “Is Your Wife Too Civilized?” To illustrate Dr. Moloney’s concept of the Okinawan style of parenting, Better Homes and Gardens used a photo of a young American mother with her baby happily secured to her back with a cloth fabric carrier—a very unusual sight in 1949! What Dr. Moloney was promoting then is very similar to what we call attachment parenting today. These pictures show an Okinawan mother wearing her baby on her back, an American mother wearing her baby in the 1940s, and a mother today wearing her baby in a sling.

28 Time, “The Cornelians.”

29 California Medical Association, Panel discussion.

Unfortunately, Dr. Moloney didn’t witness an overwhelming acceptance of the Okinawan style of parenting, but in the early 1960s, he learned about the founding of a mother’s breastfeeding group in Chicago called La Leche League International (LLLI) and spoke at one of its first conferences. LLLI became the primary organization promoting this new style of parenting until API was founded in 1994. The seeds of a new paradigm in parenting were planted.

World War II created so much devastation to the world population that scientists and researchers from around the world found unprecedented opportunities to explore and examine human behavior in a variety of contexts. The work of Dr. Alice Miller has shown how greatly culture shapes our attitudes about children. In her book For Your Own Good: Hidden Cruelty in Child-Rearing and the Roots of Violence, she gives us unsettling insight into prewar Germany and the parenting practices that were common at the turn of the twentieth century. She was fascinated that an entire society could fall under the spell of such an extremely authoritarian dictator, and she warns that unless we become more conscious in our parenting, we are destined to repeat the mistakes of past generations.

Dr. Miller researched some of the most popular parenting books in Germany during the years before and at the time that Hitler and his counterparts were children. She included passages from parenting experts of the day in her book, a compelling yet sad prediction of what laid the foundation for the Holocaust. In the later 1800s, Dr. Daniel Schreber wrote one of the most popular parenting books of the time, which went through forty printings and was translated into several languages. His advice sounds eerily similar to some parenting books that are on the shelves today. Here is an example of his advice (emphasis added):

The little ones’ display of temper as indicated by screaming or crying without cause should be regarded as the first test of your spiritual and pedagogical principle. . . . [N]ow you should no longer simply wait for it to pass . . . but should proceed in a somewhat more positive way by stern words, threatening gestures, rapping on the bed . . . or, if none of this helps, by appropriately mild corporal punishments repeated persistently at brief intervals until the child quiets down or falls asleep. . . . This procedure will be necessary only once or at most twice, and then you will be master of the child forever. From now on, a glance, a word, a single threatening gesture will be sufficient to control the child.30

30 Quoted in Miller, For Your Own Good, 5.

Of course, parents must create safe, developmentally appropriate boundaries for their children. More about this is discussed in Chapter 8. However, the key goal here is to control the child’s will before he or she remembers having a will. Domination, veneration for authority, and blind obedience are a recipe for creating a nation ripe for an authoritarian dictator, and, unfortunately, that’s exactly what happened under Hitler’s rule. Tragically, just like the children of American psychologist John Watson, Dr. Schreber’s own children suffered from severe mental illness as adults—one committed suicide and one became a famous patient of Sigmund Freud whose case was well documented in his book The Schreber Case.31

31 Freud, The Schreber Case.

The good news is that a growing number of parents and professionals have become increasingly interested in a style of parenting that actively promotes compassionate, respectful treatment of children and provides the much-needed support for the attachment relationship. The characteristics of this style of parenting are a hallmark of peaceful societies around the world and are more conducive to cooperation, compassion, and peace within the family and society. These practices have been used in some form for thousands of years—some call this kind of parenting “conscious parenting,” “natural parenting,” “compassionate parenting,” or “empathetic parenting”—some American Indians refer to it as “original parenting.” In many languages around the world, the word parenting doesn’t exist. They don’t try to define it—it’s just something that comes naturally.

The most popularized term today for this style of parenting is attachment parenting (AP), which incorporates what we believe to be the best of most parenting practices from around the world and which has increasingly been validated by research in many fields of study, such as child development, psychology, and neuroscience.

Attachment parenting is a term that was coined by pediatrician William Sears and his wife, Martha, a registered nurse, more than twenty-five years ago, early in their book-writing careers. Martha told us the story of how they came up with the term:

When Bill wrote Creative Parenting [1982], he referred to it as “immersion mothering” and “involved fathering.” At a talk one time in Pasadena, a grandmother came up to Bill and said she thought the term immersion mothering was a good one, because some moms find themselves “in over their heads.” When he told me of this, I realized we needed to change the term to something more positive [!], so we came up with AP, since the attachment theory literature was so well researched and documented, by [John] Bowlby and others.

William and Martha Sears structured the practice of attachment parenting on what they call “The Baby B’s” and offered them to parents as tools to help them build lasting bonds with their children. The Baby B’s are listed in their book The Attachment Parenting Book. The basis for these tools came from observing and talking to the many parents in their practice who had great relationships with their children.

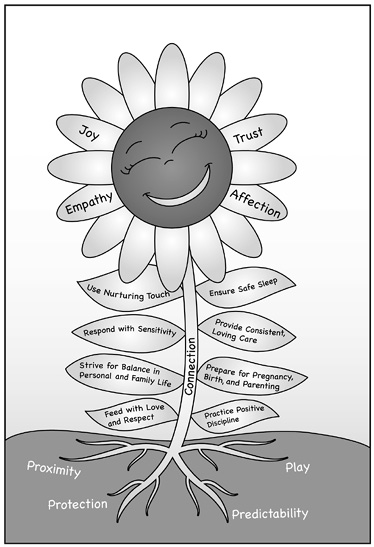

In creating API, we were inspired by the Baby B’s, so with the Sears’s blessing and input of parents, support-group leaders, and professionals, we modified and expanded them to create the Eight Principles of Parenting. We developed the Eight Principles of Parenting not as a checklist for attachment parenting but as guideposts for optimal child development supported by sound science. They are intended to provide guidance for parents as they face serious decisions and cultural pressures on a daily basis. These principles were created through the lens of attachment research and are designed to help parents become more attuned and connected to their children.

API’s Eight Principles of Parenting

1. Prepare yourself for pregnancy, birth, and parenting.

2. Feed with love and respect.

3. Respond with sensitivity.

4. Use nurturing touch.

5. Ensure safe sleep, physically and emotionally.

6. Provide consistent, loving care.

7. Practice positive discipline.

8. Strive for balance in your personal and family life.

Although the Eight Principles of Parenting were initially developed for infants and young children up to the age of five years, there are common threads inherent in each of them that are applicable to all ages. Children are born with certain innate emotional needs or drives that we believe are the catalyst for developing secure attachment. With the help of Dr. Isabelle Fox, we have created the four P’s of Innate Needs.

Studies have shown that providing proximity, protection, predictability of care, and play in the earliest years is the best investment parents can make to create secure, successful, and loving adults.

Infants best survive and have the capacity to develop into secure and loving individuals when they experience four important behaviors from their parents or primary caregivers. In most cases, nature has ingeniously programmed mothers and fathers to provide these four critical responses to rear healthy children.

1. Proximity to mother or primary caregiver to meet an infant’s innate need for security and familiarity of smells and voice of the mother or father. Proximity facilitates protection when needed, as well as timely responses to hunger, stimulation, and bodily care. Cosleeping, babywearing, and physically “being there” are behaviors that keep the infants close, and, as a result, their needs are more likely to be met promptly.

2. Protection from danger, predators, abuse, and neglect, or a baby may simply want to be protected from unfamiliar people, animals, or uncomfortable situations. Almost all species protect their newborns and attempt to keep them from harm’s way.

3. Predictability of responsive nurturing, which builds trust. It provides the infant with a familiar set of arms, smell, voice, and patterns of response. Unfortunately, in contemporary society, when parents are absent a good part of the baby’s waking hours, the frequent changing of substitute caregivers places the infant under unusual stress. The predictability of his or her world is shaken. Infants or toddlers without language or intellectual ability can’t understand why, suddenly, a stranger is feeding, holding, bathing, talking, and comforting them. Trust that their world is predictable and safe is undermined. For millions of infants and toddlers in day care, “caregiver roulette” has become the norm. (The infant never knows into whose arms he or she will land.) Such caregiver roulette occurs when caregivers change frequently, often every few months, and continuity of care is broken and trust is undermined. This can produce long-range negative consequences.

4. Play. New research supports the idea that play helps children form secure attachments and stimulates learning. Nurturing playful behavior is as important as nurturing any of the other senses. Rough-and-tumble play that is not hurtful or competitive stimulates a host of good hormones like oxytocin and endorphins. Researchers suggest that more play in childhood could prevent and reduce symptoms of ADD, ADHD, and impulsivity. The cocktail of good hormones that come from joyful play they call “joy juice” and can prevent or help alleviate depressive symptoms. It’s a healthy activity for children and adults. The act of playing also promotes secure attachment and stimulates growth hormones.

By respecting and fulfilling your baby’s innate emotional needs, you are nurturing the development of intrinsic core values—trust, empathy, affection, and joy that can last a lifetime. We think of AP as practicing the golden rule of parenting—treat our children as we would want to be treated. Our dream is that one day AP will become the mainstream way to parent, and, that as these children grow up, they will be the adults who will permanently change our culture to one of peace and respect for all living beings and the world they live in.

The following chapters are dedicated to defining the principles and providing practical strategies for everyday situations or decisions you will experience in your journey as a parent. We want to arm you with the best information available and provide you with the best resources so that you can investigate the principles more fully on your own. You are the expert when it comes to your child. Our hope is that after reading our book, you will feel more empowered to make changes and be the kind of parent and person you were meant to be.

The Four P’s of Innate Needs are the foundation, or the roots as depicted here, that feed and nourish the secure attachment relationship, nurtured in an environment of empathetic and respectful care. The Eight Principles of Parenting are our guideposts to nurturing strong connections and robust growth. All contribute to producing a hearty plant: a child (and ultimately an adult) who will have better developed capacities for trust, empathy, affection, and joy.