Chapter 2

Military Organisation

Recruitment and Obligation

The words used by Anglo-Saxons themselves for ‘army’ vary between the word ‘fyrd’ and the word ‘here’. Historically the word fyrd (from ‘faran’–to travel) has been taken to mean ‘an expeditionary force’, which may not in essence be correct. The contexts in which the words here and fyrd are used in the contemporary texts tend to point to the Anglo-Saxon fyrd being a defensive type of army and the here being an offensive kind. Both Danish and English armies could be described as a here provided they were somehow on the offensive. Few subjects, however, are more obscure and controversial in the world of Anglo-Saxon military studies as that of how the fyrd of the Later Anglo-Saxon era was suplied with its men.

It was the right of an Anglo-Saxon freeman to bear arms. Central to the historic arguments over how Anglo-Saxon armies were formed was the role of the ‘ceorl’, the free peasant warrior. Ideas varied for centuries as to whether an Anglo-Saxon army was essentially one of noble warriors who were summoned by the king in return for land and privileges, or whether it was a general levy of able-bodied freemen, or even a mixture of both. These arguments had their basis in political perceptions of the origins of Englishness and the contemporary spin that people put on it. Was the Anglo-Saxon army some sort of socialist utopia or a system more closely linked to post-Conquest feudalism and aristocratic bonds? The view often held by Victorian historians that the Anglo-Saxon army was somehow a ‘nation at arms’ is not generally accepted today but remnants of the idea of it still can be found in the modern literature.

Historians have tried to address exactly how the mechanics of military obligation worked. How would anyone be made to come to battle and what would they do if they could not? It is now generally accepted that the key to understanding how this worked is in acknowledging the mechanic that drove the whole thing–the personal lordship bond. It has been argued, with growing success, that the lordship ties that held society together were central to the military process throughout the whole period.

In the early 1960s, Warren Hollister provided a seductive solution to the whole problem, acknowledging the diversity of opinion on the matter. The fyrd was not in fact one, but two things. There was a Great Fyrd which consisted of a kind of poorly armed peasant ‘nation at arms’, and there was a Select Fyrd consisting of semi-professional, well-equipped, land-owning warriors whose obligations were based on the 5-hide land-holding unit. The linchpin around which Hollister constructed his theory was a now widely quoted passage in the Domesday Book for Berkshire: ‘If the king sent an army anywhere, only one soldier went from five hides, and four shillings were given him from each hide as subsistence and wages for two months. This money, indeed, was not sent to the king but was given to the soldiers.’ Here, then, was the Select Fyrdsman, a warrior supported by funding, whose duty was to attend the royal host. The fact that he brought money with him hints at the likelihood that there was somewhere arranged for him to spend it. But to find out why the Berkshire thegn bothers at all to turn up for the king, we need to dig deeper into history.

In the early Anglo-Saxon period, when a king summoned his fyrd, he would expect his personal retainers (‘gesiðas’, or companions) to arm themselves and would expect the duties of his ‘duguð’ (senior landed retainers with a proven military track record) to be fulfilled. The duguð were men who had served with their lord’s household throughout their youth and had been rewarded with a little land themselves upon which to found their own group of dependent men. Given the right circumstances, such a man could rise to become as powerful as the lord he served. They would turn up for campaign with their own retinues consisting of people who had received from them various gifts such as rings, treasures and war gear. Above the duguð was a senior warlord for whom all this was being done. Ultimately, the head of the kin group was the man whose influence, wealth and gift-giving capabilities were the greatest. He was the king. The very word ‘king’ comes from the Old English ‘cyning’, which means ‘chief of kinsmen’. Understandably, in a system such as this his power was immense.

Law code 51 of King Ine of Wessex (688–726) spells out the consequences of neglecting fyrd service: ‘If a gesiðcund man who holds land neglects military service, he shall pay 120 shillings and forfeit his land; [a nobleman] who holds no land shall pay 60 shillings; a cierlisc [free peasant] shall pay 30 shillings as penalty for neglecting the fyrd.’ This law is thought to reflect the structure of the earlier Anglo-Saxon armies in that when a king called out his fyrd it would consist of his own landed companions, those who owed service to these men through some other gift exchange, and the free peasants who served them.

However, by the eighth century the rise in the power and wealth of the Church had begun to throw a spanner in the works. The Church required its land in perpetuity and not just for the lifetime of the king who gave it. A system came into being called Bookland. This grant of land to the Church came with no obligations from the Church to the king except, it seems, for the securing of his soul in heaven. But for the king, it meant that the land was permanently removed from his financial and administrative system and given to his ultimate lord, God himself.

Bookland was a problem that took time to materialise but which had inevitable consequences for the kings of middle Saxon England. The more land you gave away free from military service dues, the smaller your warrior base became and potentially your kingdom would become vulnerable to other kings or raiders. The answer to the problem was found in the kingdom of Mercia. King Æthelbald (716–57) decreed that churches and monasteries could hold their land free from all dues except bridge building and the defence of fortifications. The mighty King Offa (757–96) extended this to the all-important fyrd duty. Thus, the three necessities, or ‘common burdens’, were founded. These burdens became the bedrock of military recruitment across the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England until they were modified by Alfred the Great (871–900) in his grand reforms of the ninth century.

At around the same time as the Bookland issue was being resolved there was a change in terminology being employed. The duguð was a term in decline and seems to have been replaced by the word ‘thegn’, which soon came to be a widely used term across the country. The thegn held the Bookland from the king in return for military service. The nobleman who held the large estate known as the ‘scir’, or ‘shire’, would be the ealdorman.

So, the nature of recruitment on the eve of the Viking invasions at the end of the eighth century was fairly straightforward. The armies of Anglo-Saxon England ranged from small warbands of local thegns to larger more territorial units commanded by ealdorman who were protecting their shires. Above this was the royal host called out by the king himself which in effect was made up of numerous groups of thegns, ealdormen and their retinues. All of the constituent parts of these forces came to the battlefield through the duties imposed upon them by lordship ties bound by a mixture of gift giving and land tenure.

The activities of the larger hosts throughout this period are well documented since they are the instruments of the king. Wars between Saxon kingdoms such as Wessex and Mercia, or between Mercia and the Welsh kingdoms, feature in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. But when Alfred the Great first fought the Great Heathen Army alongside his brother King Æthelred I, the chroniclers make a revealing statement about how armies were then organised. The entry for 871 says that during that year there were nine ‘general’ engagements between the West Saxons and the Danes. This figure did not count the expeditions that the king’s brother (Alfred), ealdormen and king’s thegns often rode on. The message here is clear: senior noblemen, ealdormen and king’s thegns were each capable of mounting their own military expeditions outside of the activities of the royal host. The king’s host would of course take weeks to gather together. Importantly, the chronicler mentions that these smaller forces ‘rode’ on their campaigns.

So, how did military provision change during Alfred’s reign? The answer lies in the years after the watershed Battle of Edington (878) when Alfred finally rid himself of Guthrum the Dane in a famous encounter. After Edington, over the next two decades, Alfred instigated a series of fortified places throughout his kingdom resulting in an entirely new type of defence: a defence-in-depth system in which no two forts were more than around 20 miles apart. The impact of these forts and how they were manned is examined below (see pp. 88–93), but the most important point of the reforms was that the fyrd was organised into a three-part system.

We are told by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in the entry for 894 in a passage that describes the strategic manoeuvring against the renewed Viking threat in south-east England, that ‘The king had separated his army into two so that there was always half at home and half out, except for those men who had to hold the fortresses. The raiding army did not come out in full from those positions more than twice.’ Ample evidence, then, for a system that had its obvious benefits. With a strategically gifted commander such as Alfred, and with numerous manpower resources spread deliberately over the landscape, the new kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons was to be a well-defended place indeed. This kingdom was born out of the combination of Wessex and the English parts of Mercia. Eventually, it would expand under King Athelstan (924–39) to become the Kingdom of the English. The new mechanism meant that there was always one part of the force at home on their estates, another in the field at a state of readiness and a third part on fortress duty. They could act in coordination with one another or mount their own expeditions. It was a plan based on Alfred’s own observations of the Carolingian model, which in itself probably borrowed from a papal Italian arrangement for the defence of Rome. The point is that it worked. Despite some notable problems when one Anglo-Saxon force’s tour of duty had expired before its replacements could take over from it–as happened in 893 at Thorney Island –it remains the case that the Anglo-Saxon armies of southern England were vastly better organised than they had been when the Vikings first descended upon Wessex.

Alfred’s reorganisation still required strong leadership to put into action. Moreover, one fundamental thing remained unchanged and that was the basic make-up of the fyrd. It still comprised the same people. The cost of all this, however, was immense. Inevitably, the system was doomed to be a hostage to neglect. After the reign of King Edgar (959–75) during which the Anglo-Saxons had achieved an unprecedented level of power in the British Isles, the recruitment system in part fell back upon makeshift levies based on land tenures measured in hidage. The grand fortification schemes employed by Alfred, his son Edward the Elder (900–24) and his grandson Athelstan (924–39) had in places fallen into disrepair, leaving England vulnerable once again to Viking attack. This is not to say that King Æthelred (979–1016) did not attempt to rectify the situation–in fact, far from it. Æthelred’s attempted reforms, particularly in respect of naval provision, were ambitious to say the least (see pp. 70–1). Between 1008 and 1013 the king instigated reforms which included the construction across the country of a navy of around 200 ships and the provision of mailcoats for thousands of warriors. However, all the time the king had to pay increasingly burdensome sums of money to pay off the Danes and soon he even took on a Danish contingent of his own which required feeding and provisioning.

The 5-hide unit is usually associated with a thegnly rank, this being an amount of land that qualifies its holder in that rank. However, it is clear from Domesday Book that there was great variety in the land-based obligation, varying wildly from region to region. A nobleman holding just a few hides might be required to provide a warrior, while an estate of well over 5 hides might only be obliged to provide just a single warrior. It depended on the nature of the arrangement between the landholder and the king. If an estate had to provide more than one warrior, the head of the estate would need to recruit from his tenants or find a way of replacing what he could not provide with a money payment so the king could hire a mercenary.

What seems not to have changed was the bond through lordship that drove the obligation. As if to reinforce this notion at a time when service seems to have been widely based on land-holding arrangements, the Danish king of England Cnut (1016–36) came up with a stringent law for deserting one’s lord:

Concerning the man who deserts his lord. And the man who, through cowardice, deserts his lord or his comrades on a military expedition, either by sea or by land, shall lose all that he possesses and his own life, and the lord shall take back the property and the land which he had given him. And if he has book-land it shall pass into the king’s hand.

By the time of the Battle of Hastings, it is still the case that King Harold’s army would have been recruited largely through the bond of personal lordship ties. Land tenure based on the 5-hide unit certainly came into it, but so too did the royal purse and the provision therein for mercenary hire (pp. 63–6). While not as rigidly organised as the armies of the later Alfredian period, those of 1066 were just as capable of providing results in the field.

What do we know, however, of how long it took any of these armies to gather a force into the field? We have precious little evidence to answer this question, but what little we do have points to the reasons why it was so easy for Scandinavian coastal predators to achieve so much in a short space of time. We know from the 871 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry that units of mounted men under the command of local nobles were able to put into the field almost immediately, but were small in number. Larger hosts, however, took longer to gather. Alfred’s famous call to arms of 878 issued from Athelney to the remainder of his core supporters in surrounding shires bore fruition in the seventh week after Easter, but it is not certain when the call went out. It was a nervous wait for Alfred, but when the men of Somerset, Wiltshire and parts of Hampshire answered his call, they joined him at his camp at Egbert’s Stone and were ready to march with him the next day to Illey Oak and thence to Edington.

The Danish assault on Norwich in 1004 gives a clearer idea. The Danish force seems not to have been of a size that any mounted rapid-reaction-style force could deal with. Instead, Ulfcytel Snilling, the local East Anglian leader, was obliged to play for time by buying peace from the army while he raised his force. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is specific that Ulfcytel had not had time enough to gather his own army at this point. The Danes stole away to Thetford and Ulfcytel’s order for their ships to be broken up fell on deaf ears. It was three weeks since their first assault on Norwich when the Danes torched and sacked Thetford. The following morning they prepared to return to their ships when Ulfcytel’s East Anglians fell upon them, forcing a battle. It was a hard-fought battle which Ulfcytel ultimately lost. However, it is explicitly stated that had Ulfcytel’s numbers been up to full strength the Danes would never have made it back to their ships. So it would seem then that three weeks is barely enough time to raise a sizable force to match that of the invader. This gives an idea as to the desperation of the year 1016–a year of endemic warfare in England–when King Edmund Ironside was compelled to call out the ‘national’ host at least five times for extensive campaigning.

The year of 1066 provides its own clues, although we have to be mindful of the possibilities that Harold had with him at all times a household force of a size enough to deal with all manner of problems, probably in the form of his own and his brothers’ retinues and his Danish mercenaries. Nevertheless, he decided to disband his army in the south of England on 8 September 1066, but then heard of the Norwegian invasion in the north and arrived at Tadcaster on 24 September 1066. Similarly, on his dash to London–a journey of some 190 miles–the passage of time is around two weeks, but it is clear from the sources that this was not enough time for a full host to be properly gathered. Harold’s reasons for his actions and his failure to wait at London for reinforcements may be perfectly justified based on what his strategic thinking was at the time, but once again the lesson is that two or three weeks is barely enough for a full host to form.

Quite how the fyrd was mustered is another question that puzzles historians. Messengers will certainly have been used, but did they use any devices to show the king’s will? It has been suggested from very little evidence that token wooden swords may have been used to symbolise a summons to the host. This has been based on finds of such items, sometimes with runic inscriptions from Frisia, Denmark and the Low Countries. The era is not the same (these being late Roman Iron Age or Dark Age discoveries), nor is it directly the same culture, but the intriguing possibility remains that the Anglo-Saxon messenger, when arriving at the residence of our thegn who was to prepare for war, may well have left a physical token of his visit.

The Size and Structure of Armies

The size of the armies of Anglo-Saxon England has been a subject of controversy for many years. It is generally thought that during the Migration period of the fifth and sixth centuries the average size of a warband could scarcely have numbered more than a few hundred. This much is gleaned from the historic and archaeological evidence from what is known of the Danish late Roman Iron Age Continental bog finds of warrior weaponry and what is drawn from the words of renowned ancient Roman authorities such as Tacitus. As early as the late seventh century King Ine of Wessex (688–726) was moved to categorise numbers of armed men: ‘We call up to seven men thieves; from seven to thirty-five a band; above that is an army.’ There is not a great deal that can be deduced from this code, however. Ine’s army was in fact a here. It is probably the case that fyrds and heres of the eighth century were no larger than an extended warband, perhaps numbering just a few hundred. Not until the later Anglo-Saxon period do things take on a quantifiable dimension, if only to confound us with the probability that we are only ever looking at an inherent manpower capability of a kingdom that probably never put all its available men in the field at any one time. Except, that is, for the post-reform period of Alfred’s reign.

A good example is the document known as the Burghal Hidage. Datable probably to the tenth century (see pp. 88–93), it gives specific garrison strengths for thirty-three strongholds built across Alfred’s Wessex and parts of Mercia. It even gives a formula for calculating the garrisons in term of the length of fort’s walls and the numbers of hides providing men to garrison them. The upshot of all this is that across his kingdom Alfred had a burghal garrison strength of around 27,000 men. The figure for all the land south of the Thames was probably larger in reality because the Burghal Hidage does not list the obviously cooperative Kentish strongholds such as Canterbury and Rochester, nor does it cover Cornwall. Moreover, Alfred’s kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons expanded into Danish Mercia during the tenth century to become the Kingdom of the English under Edward the Elder (900–24) and Athelstan (924–39). By the time of King Edgar (959–75), whose kingdom stretched from the south coast to the borders of Scotland, it must surely be the case that the king and his regional ealdormen were capable of raising forces in the field whose numbers were at the very lowest in their thousands.

Writing about the famous events in London in 1016, the German Bishop Thietmar of Merseburg claims he heard there were 24,000 ‘byrnies’ (mailcoats) in London. Even he thought this was incredible, so it is unlikely to be a casual exaggeration. Quite what has happened to all these mailcoats is a matter only for speculation (see p. 171). But the most obvious place to go if we want to make a guess at the near un-guessable, is to look at the Domesday Book and throw around a few figures. Judging from what we have shown so far about the apportionment of land and its division into hides, we might note that the Domesday Book records a total of 80,000 plough teams in the kingdom of England. The duty imposed by Æthelred II (979–1016) in 1008 requiring a ship from every 300 hides and a helmet and byrnie from every 8 hides would indicate on the face of it a ‘royal’ navy of 267 ships and an army comprising around 10,000 mail-clad warriors. Add to these armoured men their lesser armoured retainers at a ratio of say 2:1 and you have an army of 30,000 men. But even this figure is conservative given our knowledge of the Alfredian garrison strength of Wessex alone. Quite how many of these men took to the field at any one time when required is another matter. The actual numbers in any one army of the period must therefore have varied wildly.

One last observation on numbers goes to the Battle of Hastings. Here, the English army is harder to quantify than that of the Normans. The Norman army is well recorded and much research has been carried out as to the likely numbers who came to England in September of 1066. These figures, which are based on calculations relating to the number of recorded ships, the actual available men in Normandy and William’s mercenary contingents, in most people’s estimations amount to a force of between about 5,000 and 7,000 men. Although it is the result of educated guesswork, the consensus has been that the division of Norman forces was probably along lines of around 2,000 cavalry, 800 archers, 3,000 infantry, 1,000 sailors and logistical support men.

But what of the Anglo-Saxon army at Hastings? William apparently was told that he was likely to be swamped by English numbers when Harold’s army arrived. The English army was led by Harold and his brothers Leofwin and Gyrth, each with personal retinues numbering probably in their hundreds. We cannot be sure how many Danes were in the army, although it is suggested by William of Poitiers that these were ‘considerable’ and had been sent by the king of Denmark to help the English. To the Danes we must add the numbers of men gathered (or at least warned to attend the host) along the way. While these may have taken time to join Harold’s force and get to London, there is mention in the twelfth-century Robert Wace’s account of the regions from which the king recruited his force. These comprised the men of London itself, Kent, Hertford, Essex, Surrey, St Edmunds, Suffolk, Norwich, Norfolk, Canterbury, Stamford, Bedford, Huntingdon, Northampton, York, Buckingham, Nottingham, Lindsey, Lincoln, Salisbury, Dorset, Bath, Somerset, Gloucester, Worcester, Hampshire and Berkshire. We cannot be sure how authentic this evidence is, or whether each of the regions answered their call. It does not represent the entire ‘national’ host, either, which may be why William of Malmesbury suggested Harold’s numbers were not as high as they might have been. However, if we assign an unlikely low figure of 200 men per place mentioned, we come up with a force of 5,400 men before we have even added our Danes and earl’s retinues. It is small wonder then that when William of Poitiers (borrowing his style from the ancients) described the English army emerging from the Wealden forest to the north of Senlac Ridge he said, ‘If an author from antiquity had described Harold’s army, he would have said that as it passed rivers dried up, the forests became open country. For from every part of the country large numbers of English had gathered.’ If the numbers themselves are difficult to pinpoint, the evidence outlined above must surely suggest that the Anglo-Saxon military system, however allegedly archaic and obsolete by 1066, was capable of sending a force of up to 10,000 or more men to Senlac Ridge that October morning. We should not underestimate this capability.

But what form did these armies take in the field? How were they structured? At the top, of course, was the chief kinsman, the king. Around him in the later period were the men who constituted his household retinue, heavily armoured infantrymen. Also at the king’s disposal from the time of Æthelred were the Danish mercenaries available as a separate subordinate command, probably protected with mail armour and equipped with Dane-Axes. Further still, according to Wace in his Roman de Rou, the men of London fought around the king, presumably as heavy infantry spearmen. Wace also tells us that it was protocol for the Kent fyrd to be the first into battle. John of Salisbury also recalls this right of the Kent fyrd, a very prestigious right, but he adds that after Kent, the next in order to fight would have been the men of Wiltshire, Devon and Cornwall. The king’s close kinsmen, such as brothers and sons (æthelings), would have their own entourages around them with the exception of the mercenaries and Londoners. If they were all travelling together, the size of this force alone would have been considerable. Next, the regional ealdormen, or earls, who took their place would also form separate command units and they would bring along with them the thegns and their men, the ceorls, or free peasants from their estates, armed and equipped variously. These forces were organised by shire, hundred and ‘soke’ (private holdings). It is very clear that the armies of the later Anglo-Saxon period were both numerous and structured.

Heriots

Many of the warriors of Anglo-Saxon England came to the battlefield armed and armoured, but how did they come to possess such equipment? The inclusion of heriots, or ‘war-gear’, in some surviving Anglo-Saxon wills of the later period provide us with a glimpse into an ancient custom and an insight into the importance of the bond of lordship throughout the period. A heriot (‘heregeatu’) was basically a death due liable for payment from people of thegnly rank or higher. It was in essence the returning to one’s lord of the military equipment that the warrior had obtained for taking service with his lord in the first place. The broad notion behind it was that by returning the arms and armour given to you by your lord on your death, your lord would be able to attract the service of another warrior to his household. The poem Beowulf is full of the giving of such arms by a lord to his man. For the modern historian, the heriots reflect the nature of military service in terms of numbers of men and equipment that was expected of different ranks of society. Although only broad conclusions can be drawn, they are useful nevertheless.

The giving of arms was deeply rooted in Germanic custom. In Anglo-Saxon England it continued over a period of centuries whereby it is possible to see a trend developing over time. According to surviving documentation it would seem that in the Danelaw heriots were often paid in hard cash instead of arms and armour, although the one surviving will of a man called Ketel, an eleventh-century thegn of Archbishop Stigand, shows that arms and armour could still be the method of payment even in the Danish areas. For such a thegn the material in question centres around his horse and his weapons and armour, enough to equip one man. Generally, the higher up the social rankings you were, the more arms and armour you were required to provide. There are sixteen heriots mentioned in the wills stretching from 946 to the period immediately preceding the Norman Conquest. Some of them include material additional to the basic weapon and armour set such as one with a handseax, and one with a javelin. There is also mention of hawks, deerhounds, cups and dishes in some of them.

In short, as the heriot of Ketel shows (1052–1066), it is possible to determine that the war gear for one well-armed aristocratic warrior amounted to one horse with tack, one helmet, one byrnie (mailcoat), one sword, one spear and one shield. But it had not always been this straightforward. The earliest surviving heriots of Ealdorman Æthelwold (946–947) and Bishop Theodred (942–951) would seem to have been based on the rating of an ealdorman at the time of King Edmund I (939–46). Here, the provision is for four men with horses, swords, shields and spears. There is no mention in these heriots of helmets or byrnies or of additional unsaddled horses, spears and shields for retainers as there is in later heriots. It seems the early requirements were fairly straightforward and centred round multiples of two. Noticeably absent from all heriots, of course, is the bow, not a weapon to be associated with Anglo-Saxon nobility.

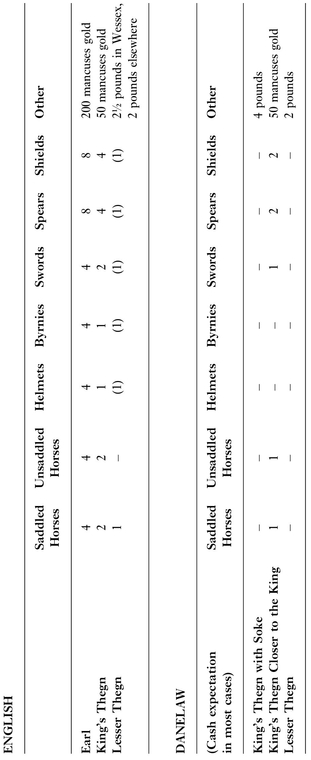

During the reigns of Eadred (946–56) and Edgar (959–975) the requirement seems to escalate with multiples based now on a factor of three. For example, the heriot of Ealdorman Ælfheah (968–971) is rated at six horses, six shields, six spears and six swords. The tendency to increase the heriot of the highest ranking member of society reflects a royal concern with the defence of the realm. By the time of Æthelred II (979–1016), there is a further evolution, which although complex, is possible to interpret. The ealdorman rank or its equivalent goes up from six of everything to four fully armed and armoured men and four lesser armed men with the appearance of the helmet and byrnie for the first time. In fact, all heriots appearing after 1008 contain helmets and byrnies, probably reflecting Æthelred’s decrees about the increased production of such armour throughout his kingdom (see p. 171). It is this evolution that is represented in the law code II Cnut 71 (1020–3), which sets out specifically the heriots owed by different ranks. Here, we can see the discrepancy between the expectations of the men of the Danelaw and those of other parts of the kingdom.

It is clear that an earl’s heriot represented the equipping of four fully armed men and four attendants to them equipped with just spear and shield. Each of them rode to battle. It is not clear how the unsaddled horses were used. They may have been used as pack horses to carry baggage or may have been ridden without saddles by the four lesser armed retainers.

Table 2. Anglo-Saxon heriots at the time of King Cnut, 1020-3.

The king’s thegn of the English list seems to have been expected to provide one fully armoured man (presumably the king’s thegn himself) and one lesser armoured man who has a saddled horse, sword, spear and shield, but no helmet or byrnie, plus two attendants with spear and shield looking after two unsaddled horses. The lesser thegn is listed as one might expect. He has to bring to the battle just himself, fully armed and prepared.

The Danelaw evidence is more problematic. There seems to be a cash payment expectation for a ‘king’s thegn with soke’ and for a lesser thegn, but quite why the ‘king’s thegn closer to the king’ is rated at two horses (one saddled), one sword, two spears and two shields with no helmet or byrnie listed is a mystery. It seems unlikely that the late Anglo-Saxon kings were not able to impose such a burden on the Danelaw given that Æthelred had demanded many coats of mail to be made across his kingdom.

Heriots later became less militarised and more associated with the concept of tenurial succession. The difficulty is in trying to apply them to the given military situation at the time of their writing. If they provide nothing else, heriots give us a general idea of the type of equipment an Anglo-Saxon warrior was expected to possess in order to do his duty. When he performed that duty, the warrior became part of a well-organised machine and not, as some have contended, an ad hoc reaction to the latest crisis.

Logistics and Communication

King Harold lost the campaign of 1066. This fact has tended to deflect our enquiries into the effectiveness of logistics in this era. Often we assume there was inadequate provision in Harold’s army or that what existed was somehow archaic. But we do not give sufficient credit to the Old English military system. Here, we must concern ourselves with the evidence for the wider apparatus of how forces were supplied and informed on their long campaigns. That the earlier Anglo-Saxon kingdoms possessed the capability of large-scale feats of organisation is surely evidenced by the building of Offa’s Dyke (Plate 1, and see p. 87).

King Alfred’s three-way split of fyrd service into garrison service, army service and land service is our first clue that logistics were to be a central part of military planning. The forces were rotated so there were always fresh men to hand, but we are not told how they were provisioned in the field. Later sources indicate the fyrdsmen were supposed to supply themselves, but as we have seen they were to bring money with them indicating that there must have been an arrangement for them to spend it at certain markets or on certain things. The Frankish Annals of St Bertin record that shield-selling merchants were present in the baggage train of Charles the Bald at the Battle of Andernach in 876. It is difficult to dismiss the notion that such arrangements must have been made in England.

The idea that a campaigning army sent out its own foragers is supported by some early evidence. It would also appear that such men acted as scouts for the army too. The Venerable Bede indicates that the men in the baggage train of early Northumbrian armies were married poor peasants whose job it was not to fight as such, but to bring provisions to the troops. This is a specific reference to the thegn Imma, who after the Battle of the Trent in 679 disguised himself as such an individual to escape capture and recognition by his captor’s kinsmen. He declared that he had come on campaign with others of his kind to bring provisions to the troops. His enemies in the Mercian army clearly bought his story. It is likely that Bede’s thegn Imma was among those responsible for managing the baggage train. It is tempting to see this sort of arrangement running right through the period as a whole.

Evidence from France suggests that men summoned to the Carolingian host were to bring with them enough provisions for three months in carts. Meat and other such provisions, it is argued for the Carolingians, was brought on the hoof or in carts. Supply dumps were arranged in advance and other foraging was undertaken while on campaign. Again, the likelihood of similar arrangements in Anglo-Saxon England is very high, but as always, much harder to find. Those responsible for overseeing supply dumps of hay for horses, grain and ale etc. may well have been the royal horse-thegns who were thought to have performed a role similar to their Frankish counterparts, the Marshalls (Marescales), whose association with mounted logistics is inherent in their title.

Despite the extreme likelihood that the level of organisation in terms of supplying an army in the field was very high, there is evidence that it could all go horribly wrong during a campaign. The sheer volume of produce required for supporting an army meant that it might have to engage wholesale in foraging. After Alfred’s death, during the campaign of Edward the Elder against the renegade Æthelwold, which is described below (see p. 101), the king’s Kentish contingent (traditionally in the van of a combined Anglo-Saxon army) ignored the royal pleas brought to them by no less than seven messengers to come out from East Anglia after playing their part in a punitive campaign. It is argued that the Kentish refusal to obey the king was due to the fact that they had dispersed in order to forage for supplies.

The scouts and foragers in the army, particularly those of the border areas will have had great knowledge of route ways and track ways in their area. The route ways and roads of Anglo-Saxon England were both a result of thousands of years of evolution and, in some cases, brand new innovation. For example, the Icknield Way, which is generally regarded as the oldest road in England, running from Knettishall Heath in East Anglia in a diagonal line across the heart of England to the West Country for 105 miles, probably had its origin in the Neolithic period some 3 millennia prior to the Anglo-Saxon era. The Danish Great Heathen Army is even thought to have boldly marched down this ancient track to attack Wessex in 871.

On the other hand, parts of the surviving Roman road network were still very much in use with the old roads given English names, such as Watling Street. That the Roman network was still widespread is undoubted. Its state of repair may have varied, however, and there is one reference to a Roman road in the bounds of a Chiseldon charter, dated to 955, which names the road as ‘brokenstret’. However, the building of a grand fortification scheme in southern England by Alfred the Great certainly took advantage of the Roman network. From Exeter you could travel along Roman roads north to Bath, Cricklade, Malmesbury and Axbridge and east towards Winchester via Bridport and Wilton and, of course, on to London.

There are, however, fascinating and repeated references to track ways that appear to be dedicated to military usage. In many charters from the Anglo-Saxon period the word ‘herepath’ appears in the bounds. In fact, there are 41 ‘herepaths’, 3 ‘fyrdstreats’ and 4 ‘herestreats’. Today, where these paths survive, they are often referred to confusingly as ‘people’s paths’. But in Anglo-Saxon times it is probable that these paths represented a specific network of minor roads dedicated to the assembling and quick transportation of forces between towns, fortifications, monastic centres and estates. Some examples seem to run parallel to Roman roads indicating their exclusivity, such as the A350 in northern Dorset and the A30 in Wiltshire. Where a Roman network may not have existed or where it was inadequate for the new military needs of a region, we find herepaths being used to link outlying estates to royal vills or monastic centres. Such is the case with the herepaths mentioned in the boundaries of Corston, Priston and Stanton, which were three estates belonging to the monastery at Bath.

Another example of a herepath is one that seems to have run from Wroughton in Wiltshire to the burh of Marlborough, travelling through Yatesbury and the ancient monument at Avebury. Archaeologists contend that of the four entrances to the great prehistoric monument at Avebury, the eastern one is likely to have been either made or substantially altered by the Anglo-Saxons to accommodate the herepath that ran through it. This herepath is thought to be early tenth century in date and would have represented an era when Edward the Elder (900–24) was working to consolidate his hold on Wessex while actively seeking to expand his kingdom to the north. The Yatesbury Lane herepath linked the minster church at Avebury to the burh and along its route around the Marlborough Downs was a small defended enclosure at Yatesbury, the ditches of which are dated to the Anglo-Saxon period. This represents an effort on the part of the Anglo-Saxon military planners to make defensible even the smaller enclosures along the route ways of the kingdom. The Yatesbury Lane herepath, like many others, also commanded good views of the surrounding landscape along its route. Many herepaths are associated with ridge ways probably for this very reason. A picture emerges then of a surprisingly sophisticated level of military planning by the Anglo-Saxon kings of England.

What a herepath actually looked like is another question. They do not seem to have been metalled roads in the Roman sense, but the one at Yatesbury Lane had a ditch on one side only and was about 5m wide, with some tantalising geophysical evidence for wheel ruts. Elsewhere in the Somerset Quantocks these track ways are described as 20m or 64ft wide. Quite how often an English warrior’s boots trod down these pathways and intricate networks is unknown. Nor is it understood how often herepaths were used for logistical provision between towns and forts throughout the kingdom. What little evidence we have once again points to a level of sophistication that perhaps should not surprise us.

If the herepaths of the kingdom could aid transportation and supply of troops and goods, then what do we know of any early warning systems? There is a growing body of evidence to suggest that the Anglo-Saxons had an elaborate system of beacons dotted around the countryside. The very word ‘beacon’ is Old English in origin and comes from the word ‘becun’. But it is suggested that there are other words in Old English that imply a place name of a similar function to a beacon site. Such words are ‘weardsetl’ and ‘tot’. Weardsetl, which means ‘watch point’, appears in a number of charters from the Anglo-Saxon period and tot was another name for a look-out point. The key to these systems was in their inter-visibility. One fire lit on the Isle of Wight could by a series of relayed fires get a message to the Thames Valley in a very short space of time.

The systems seem to have been related to the office of the coastal watch. This duty seems to have been divided across the ranks of later Anglo-Saxon society. Æthelweard, our much quoted chronicler, held land granted by Edward the Martyr (in 977) at St Keverne, Cornwall ‘free from all royal dues except military service and the fortification of fortresses and maritime guard’. Here the expected bridge work is replaced by the coastal watch and it seems Æthelweard’s responsibilities were great indeed. However, an ealdorman could clearly not watch the sea all by himself, which might be why an eleventh-century document known as the Rectitudines Singularum Personarum (the ‘Rights and Ranks of the People’) describes some of the duties of a thegn as arising out of the king’s command to include equipping a guard ship and guarding the coast. Nor did it stop with the thegn. The same document also mentions the cottar’s right. The cottar, a peasant freeman, is referred to as having to perform the duty of keeping a coastal watch.

The mechanics of the coastal watch may have worked by the cottar keeping watch on the coast under the instruction of the thegn whose duty it was to organise it. Any sighting of an enemy fleet would cause the cottar to light the first in a chain of beacons leading inland along sight lines carefully prepared. The result would be the early warning to the population who could flee their homesteads and get to the burhs and other fortifications in plenty of time. A picture emerges, then, of a landscape dominated by signalling and communications networks no less effective than the beacon systems of the days of the threat from the Spanish Armada, the very organisation of which seems to have been largely based upon its Anglo-Saxon predecessor.

The evidence for Anglo-Saxon beacon systems is overwhelming, even though their study is still in its infancy. For example, evidence of London’s defence is provided by a tot site at none other than Tothill Street in Westminster (Plate 18), near to which archaeologists believe was an artificially created mound set up for the purpose of such communication. There is also evidence that the herepath system was inextricably linked in with the beacon system, with roads identified as far away as Beaford in North Devon leading directly into Oxford Street in London, where a charter records a ‘here-strete’, possibly identifiable with the Lunden herpathe of a charter of 909. At Nettlecomb Tout in Dorset a beacon seems to have been placed directly on the course of a herepath. A further postulated system exists along the line of the old Roman road Stane Street, running from Chichester to London, where out of fifteen identified sites six contain the place-name element tot. At the seaward end of the system would have been the seawatch beacon at Chichester. There are hints in the sources that these grand civil-defence systems were much vaunted by the Anglo-Saxons and that their Viking enemies took some pride in out-manoeuvring the English in such deeply defended landscapes as the campaigns of 1006 may demonstrate (pp. 13–14).

Logistics seem to have played a part in joint land and sea operations. Whether ships supplied campaigning forces with victuals alone, or strategically landed fresh troops or reduced areas of coastline is unknown. One suspects a mixture of all these. Athelstan’s grand campaign of 934 in Scotland can only have been sustained with support from the sea. Also, King Edmund I’s (940–6) extraction of support from Malcolm of Scotland was to include a promise of support on both land at sea. Other examples include Earl Siward’s Scottish expedition of 1054 against Macbeth and Earl Harold’s combined operation alongside his brother Tostig in Wales in 1063. In the analysis below, of the mounted provision, mercenary provision and naval provision in Anglo-Saxon England, the administrative and logistical capability of the Anglo-Saxons is a central theme. Despite the huge expense of maintaining such a system and despite changes and a subsequent decline in the later tenth century, the king of England in the early eleventh century had at his disposal a capability the envy of any ruler of Christendom. Perhaps this explains why, in 1066, so many people wanted it for themselves.

The Question of Cavalry

An earl belongs on the back of a horse. A troop must ride in a company, a foot-soldier stand fast.

Maxims I, 62–3

The question of the existence of an Anglo-Saxon cavalry is another area of controversy. People have assumed that the Anglo-Saxons fought only on foot and had very little knowledge of horses, rarely putting them to any military use. The reasons for this long-standing view are complex and numerous. Certainly, there are historical sources who say that the Anglo-Saxons were unable to fight on horseback and that the use of the horse as a tactical option on the battlefield was unknown to them. This goes back as far as Procopius in the seventh century. References to the English sending their horses to the rear while their riders proceeded to fight on foot are known from the accounts of the Battle of Maldon and the Battle of Hastings. Also, we have to contend with the twelfth-century historian Henry of Huntingdon’s assertion that the English did not know how to fight on horseback, and The Carmen’s acerbic remark that

A race ignorant of war, the English scorn the solace of horses and trusting in their strength they stand fast on foot and they count it the highest honour to die in arms that their native soil may not pass under another yoke.

With propaganda like this, it is easy to see why the Anglo-Saxons’ reputation for not having a cavalry has stuck for so long. Modern historians have tended to reinforce the notion of the Anglo-Saxon lack of cavalry by producing sometimes quite astounding theories. The lack of evidence for metal stirrups until the arrival of the Vikings, for example, is often put forwards as a reason the English could not possibly have adopted mounted tactics, because their riders would somehow be unsteady in the saddle. The fact that the native English horse was ‘no more than a pony’ is the often peddled nonsense in support of the English ignorance of cavalry. Thankfully, the tide is turning on these theoretical points due to recent research. The stirrups need not be an issue for horsemanship, and in any case the lack of evidence for metal ones does not preclude the existence of wooden or rope equivalents. In fact, the Old English word for stirrup was ‘stigrap’, which literally means ‘climbing rope’. Also, studies of horse management in England prior to the Norman Conquest and the archaeological evidence to support it show the Anglo-Saxon horse to be the physical equivalent of its Continental cousin. The problem is this: people have made assumptions about the Anglo-Saxons’ mounted skills based on not only Norman propaganda, but on the knowledge that the Normans themselves were consummate cavalrymen. Their ‘destriers’, it is correctly argued, could charge home on the battlefield and their riders were trained to use the couched lance style of fighting on the battlefield, a famously impressive tactic. Their cavalry charges attracted comment from the Byzantine writer Anna Comnena, who spoke of the Normans being able to ‘break the walls of Babylon’. It has to be said that there is no evidence that the mounted Anglo-Saxon ever fought in this way. And so, all of this leaves the reputation of the Anglo-Saxon horsemen with a lot of ground to make up.

However, when we examine the evidence for the presence of the mounted Anglo-Saxon, we find that for years we have probably been asking the wrong question. It is not a matter of whether the Anglo-Saxons had a ‘cavalry’ as such. There has been a refreshing move away from this polarised argument in recent years with an acknowledgement that the Anglo-Saxons usage of horses by way of mounted infantry was so widespread as to blur the distinction between foot and horse. The evidence is overwhelmingly in favour of there being mounted troops employed on a very wide scale and the importance of a nobleman’s ownership of horses is clearly outlined in the heriots of the age. It is rather a question of ‘how did the Anglo-Saxons employ their horses in a military context?’

As early as the eighth century the Venerable Bede mentions the importance of the horse in the context of royal gift giving. King Oswine (644–51) gave a royal horse to St Aiden. From the pagan Saxon period there is a horse burial at Lakenheath which shows us that the value of the animal has a great ancestry among the Anglo-Saxons. In a military context, an early reference to the Anglo-Saxon use of cavalry on the battlefield is captured on the Aberlemno Stone, which depicts a Pictish and Northumbrian army both fighting on horseback at the Battle of Dunnichen in 685.

With the arrival of the Danes in East Anglia in 865, the references to mounted bodies of men, both Danish and English, appears with great frequency in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. The very fact that the Danes horsed themselves from East Anglia points to the existence of royal or ecclesiastical stud farms across that kingdom. Such horse management is no light matter. A charter of the English ‘puppet’ King Ceolwulf (874–c. 80) of Mercia dating to 875 refers to the freeing of ‘the whole diocese of the Hwicce from feeding the king’s horses and those who lead them’. Given that a horse can consume 12lb of grain and up to 13lb of hay each day as well as gallons of water indicates this was quite some reprieve for the people of that ancient district. The fact that horses were actively employed in small military units under the command of senior nobles is evidenced by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for 871, which talks of uncounted individual mounted forays. These smaller actions were almost certainly the English counter response to the Viking’s necessity to send out their own small foraging parties.

Fig. 3. Abraham’s Army in Pursuit of Lot’s captors, from the eleventh-century Old English Hexateuch.

The terms used to describe mounted forces in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle are two-fold. They are either described as ‘gehorsedan/ra’ (867, 877, 1010 and 1015) or ‘rad(e)-here’ (891). These terms often apply to the Danes and there is some ambiguity regarding the first term being an English word indicating a ‘horsed’ body of sorts. However, the second term contains the familiar element ‘here’. This has more militaristic connotations of a mounted troop on the offensive. The Danes are sometimes described as being outmanoeuvred in the landscape by mounted Anglo-Saxons. Such an example is the young Edward the Elder’s out-riding of the Danes in the Farnham campaign of 893. But it is to the chronicler Æthelweard that we owe a revealing reference to a sizable force of mounted Anglo-Saxons. Using the Latin term ‘equestri’, he describes Ealdorman Æthelhelm of Wiltshire’s preparation and execution of a giant mounted force to chase the Danes ultimately to a retreat at Buttington, where they were surrounded and besieged in 893. Æthelweard, a nobleman himself, would not have used the term ‘equestri’ if he had not meant to.

If none of this is enough to convince us that there were separate mounted contingents in the Anglo-Saxon army, then the quote from Maxims I at the beginning of this section might assist. It refers to the noble affiliation of the Anglo-Saxon horseman and the need for a mounted body to ride ‘in a company’ (‘getrume’, meaning ‘firm’) and for a foot soldier to hold his ground. A clear distinction is made between the two types of unit and their cohesive requirements.

When we come to the end of Alfred’s reign and the reigns of his son and grandsons, we can see a great deal of evidence for the proper management of horses in a military context. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for 896 refers to two horse-thegns, whose rank was high enough for them to be included in a list of important people who had recently lost their lives:

Of these one was Swithwulf, bishop in Rochester, and Ceolmund, ealdorman in Kent, and Beorhtwulf, ealdorman in Essex, and Wulfred, ealdorman in Hampshire, and Ealhheard, bishop at Dorchester, and Eadwulf, the king’s thegn in Sussex, and Beornwulf, town-reeve in Winchester, and Ecgwulf, the king’s horse-thegn, and many in addition to them, though I have named the most distinguished . . . The same year, Wulfric, the king’s horse-thegn passed away; he was also the Welsh reeve.

The horse-thegn’s role is unknown, but is likely to have involved the organisation of horse management and breeding in their areas and for the provision of horse fodder, particularly over the winter months when foals and mares would need nutrition to avoid stunted growth. It was probably similar to the French Marshalls or Constables (literally ‘count of the stable’). Later, in the eleventh century the office of Staller appears in the record. Many Stallers are described by the Normans as Constables in 1066.

King Athelstan (924–39) was concerned enough about the giving away of horses as to decree ‘that no man part with a horse over sea, unless he wish to give it’ (II Athelstan 18). It is generally thought this indicates a royal desire to control the practice of open horse trading to potential enemies outside of the tradition of gift giving in arrangements such as marriages. Another code of Athelstan’s (II Athelstan, 16) demands that two mounted men be provided from every plough in a landowner’s possession. Once again, the importance of mobility is paramount in the king’s mind. Athelstan, by 927, was in the process of building a vast empire and he knew that this could not be achieved without mobility.

Studs had been under pressure during the period of Viking depredations in the decades gone by. But since 919 the English kings had harboured at court some Breton exiles, famous for their horsemanship. Their influence over the English horse stock in terms of Arabs and/or Barbs is not properly understood, but into the equine mix in 926 came an offering from abroad of great magnificence. William of Malmesbury tells us of a gift to Athelstan from Hugh, the Duke of the Franks, which included horses:

he [Adulf, the leader of Hugh’s mission] produced gifts [at Abingdon] on a truly munificent scale, such as might instantly satisfy the desires of a recipient however greedy: the fragrance of spices that had never before been seen in England; noble jewels (emeralds especially, from whose green depths reflected sunlight lit up the eyes of the bystanders with their enchanting radiance); many swift horses with their trappings, ‘champing at their teeth’as Virgil says . . .

Just how many horses or what breed they were we do not know. Frankish horses were often obtained from Spanish stock. One wonders, with his system of horse-thegns and royal studs, whether a breeding programme may have sprung from the gift somewhere in the fields of southern England. Perhaps it is significant that a grand campaign in Scotland was undertaken in 934 at about the time some of these horses or their offspring would have been ready. Perhaps also the reference to mounted action in The Battle of Brunanburh (937) is no poetic device, but a statement of fact:

All day long

the West Saxons with elite ‘cavalry’

pressed in the tracks of the hateful nation

with mill-sharp blades severely hacked from behind

those who fled battle.

This reference to ‘elite cavalry’ may seem overstated. The Old English word used is ‘eoredcystum’, from ‘eoh’, taken by some–but by no means all–to mean ‘war horse’. But it raises the final and most vexed of all questions. We have surely established the existence of an independent mounted arm in the Anglo-Saxon military toolkit. But how was it employed–if at all–on the battlefield?

The Battle of Brunanburh reference seems to point to the retaining of a mounted reserve fresh for the chase. It was in the rout where the most enemy casualties were accrued and here we have a dedicated body of mounted men prosecuting the rout from horseback using swords. So, English armies fought on foot, but sometimes prosecuted the rout on horseback? Unfortunately, there are further references to the mounted Anglo-Saxon in action and each of them presents its own difficulty of interpretation. For example, when the visiting Norman Eustace of Boulogne allowed his men to run amok in Dover in 1051, the English response was swift and, it appears, on horseback. The chronicler refers to great harm being done ‘on either side with horse and also with weapons’. Four years later, in 1055, there is a reference most often quoted in support of the theory that the English could not fight on horseback. Let us examine it. John of Worcester’s chronicle entry describes the pre-Conquest Norman Earl Ralph of Hereford’s attempt to get the fyrd to fight mounted. Here, at the Battle of Hereford, he is said to have ordered the English to fight on horseback ‘contrary to their custom’ (‘contra morem in equis pugnare jussit’), but the earl with his French and Norman cavalry fled the field and Worcester goes on to say ‘seeing which, the English with their commander also fled’. The enemy of the Hereford force, which comprised the men of the exiled Anglo-Saxon Earl Ælfgar and the Welsh king Gryffydd, gave chase and slew 400 of the fleeing English forces. It would be hard to see how this could have happened if Ælfgar’s own forces were not mounted. There is no real problem in translation. The phrase ‘contra morem in equis pugnare jussit’ means the English were ordered to fight contrary to their custom, on horseback. But what does it imply? Does it mean that being horsed from the outset and being asked to fight a full cavalry battle in the manner of their Norman commander was the alien concept, or was it that the English simply had no idea of horseback warfare? It is surely the most probable interpretation that, at Hereford, the mounted Englishmen were asked to fight in a way they knew little about, and not that they knew nothing of horseback fighting. And as for the quality of their horsemanship, perhaps we should remind ourselves of who broke first that day.

Finally, the account written by Snorri Sturluson in Heimskringla of repeated English cavalry charges upon the Norwegian lines at Stamford Bridge (1066) is perhaps not reliable evidence. It was written in the thirteenth century by a man who admitted in his own prologue that the truth of his accounts was based only on what wise old men had passed down. There is confusion over the 1066 campaign in this account and what Snorri has to say about the cavalry charges at Stamford Bridge smacks much more of Norman tactics at Hastings.

So, what can we conclude about Anglo-Saxon mounted warfare? The ownership of horses was a nobleman’s obligation, supported by royal legislation and systems of management. The English use of a mounted infantry arm is strongly supported by the evidence, as is the existence of separate dedicated mounted forces. The ranges over which they campaigned were vast, and they often overtook their mounted enemies, out-manoeuvring them in the landscape. There is no evidence at all that the Anglo-Saxon armies fought cavalry battles in the style of the Normans. On a tactical level, all the evidence points to the dismounting of riders and the fighting of the battle on foot in a time-honoured tradition. In fact, the sending of the horses to the rear prior to the onset of a battle was not even an exclusively Anglo-Saxon thing. As a way of demonstrating defiance ninth-century Franks and twelfth-century Normans did it as well. The ‘defying’ aspect was the fact that once dismounted, the army could not easily run away from the battle.

There is, however, tantalising evidence to support the theory of a mounted reserve being retained for the chase at a tactical level, as at Brunanburh. The great change that came with Anglo-Norman warfare of the twelfth century was the usage of the mounted knight at a tactical level. This was a time when the first histories of Anglo-Saxon England were being written. The Anglo-Saxons’ usage of a mounted arm and that of the Anglo-Normans are incomparable and contemporaries knew it. On the one hand, we have a widespread mounted infantry philosophy accompanied by limited cavalry activity on the battlefield, while on the other we have the famous charging Norman milites riding around in their squadrons of well-trained cavalrymen.

There is one last word on the reason for all the confusion. If we could transport ourselves back in time and observe King Alfred’s noblemen riding to chase down the Danish foragers, to Ealdorman Æthelhelm’s march to Buttington, to Edward the Elder’s overtaking of the Danes at Farnham, to King Athelstan’s victorious pursuit of the retreating confederates at Brunanburh and to King Harold’s swift response to crises at either end of his kingdom, we would not be able to avoid one observation. The Anglo-Saxon army looked like a cavalry force. They simply got off their horses (for the most part) when it came to the important matter of sword play. Similarly, the Danes obliged by behaving in much the same way. With the Normans came a watershed and the dawning of a new era in mounted warfare in England. By the twelfth century the age of the brave warrior hero who faced his opponent on foot was all but gone.

Tributes, Gelds and Mercenaries

It is important to distinguish between two forms of payment raised throughout the age of the Viking invasions by the English kings. On the one hand there was ‘gafol’, a form of tribute payment to the enemy. On the other, there was ‘heregeld’. Heregeld was an annual ‘army tax’ first instituted in 1012 by Æthelred II (979–1016) to pay for the mercenary services of Thorkell the Tall. It remained in use until it was abolished by Edward the Confessor in 1051. When the idea was re-kindled by the Anglo-Norman monarchy its name ‘Danegeld’ recalled its very first purpose. The tax was based on landownership and was assessed at a certain number of pence per hide and it was collected at fixed times each year through the hundreds in the shires.

There are hints that gafol payments predated the heregeld policies of Æthelred. It could be the case that King Alfred’s (871–99) trouble with his own archbishop came from a practice of raising tribute money through the church to pay off the Vikings in the early years of his Danish wars. Gafol was not set at a fixed amount and could be raised by almost any means in an emergency. It is sometimes mentioned alongside the word metsunge (indicating ‘feeding’ or ‘provisioning’), which in its own way narrows the gap somewhat between the two types of taxation, both of which provide a means of support for the foreign force with differing degrees of reciprocity.

The payment made in 991 to the Danes of 10,000 pounds of silver was described as gafol by the chronicler and it was said to be the first payment (of the new age of invasions). Again, in 994 King Æthelred offered the Danes gafol and metsunge if they would leave off their raiding. This time it was 16,000 pounds and the Danes took up winter quarters at Southampton and were fed from the land of Wessex. It seems a heregeld was also paid in this year totalling 22,000 pounds. Again, in 1002 the king and his councillors agreed to pay 24,000 pounds in gafol and metsunge. In 1006–7 a colossal gafol of 36,000 pounds was paid. In 1009 to the misery of the men of East Kent a further 3,000 pounds was paid to get the raiders to leave. In 1012, it reached a huge 48,000 pounds. The next year saw a slight variation in terminology. The invading Dane Swein demanded ‘gyld’ and metsunge to over-winter, while Thorkell demanded the same for his fleet at Greenwich. After his return from brief exile in Normandy King Æthelred kept the payments to Thorkell. In 1014 a gyld of 21,000 pounds was paid to the Greenwich fleet. In 1018, after the wars with Æthelred and his son had been won and Cnut was king, the heaviest tax of all was levied at 72,000 pounds from across the kingdom and separately a sum of 10,500 pounds from London. This last was described as a gafol, but the circumstances of Cnut’s levy are, of course, somewhat different to the earlier ones, given that he was now the Dane in the ascendancy.

It is clear then that some payments were to bribe the enemy to stop its raiding, while the others were literally to support or employ them. So, what use was made of these mercenaries over the years and who were they? The identity of Thorkell the Tall is clear enough, but it is not always that easy to distinguish the mercenary. First, we must be careful how we use this term. Increasingly, towards the end of the period men turned up on the battlefield who, despite their military obligation to their lord, may have had a stipendiary penny in their pouch as well. But these are not true mercenaries as such. Nor, for that matter, are the many groups who fought alongside Anglo-Saxon leaders as military allies. There is a distinction between the hired man (‘hyra-man’), who became familiar to the court of Alfred the Great as his wealth increased, and the fyrdsman, whose loyalties were based on more traditional lordship bonds and land tenure. Neither of these two categories could be said to be true mercenaries.

An example of the difficulties in interpretation might be the household hired men of King Alfred’s court. These men were bound to Alfred through love of their lord, but were rewarded not just by the old-fashioned gift and ring-giving mechanisms of yesteryear, but also by hard cash. Their roles within Alfred’s kingdom were manifold. Some would be messengers, horse-keepers and administrators as well as warriors. The English economy in the Viking period was becoming more monetarily based and Alfred was able to leave 200 pounds in silver coins to these followers on his death. These men were not mercenaries.

The same may not be said for Alfred’s Frisian sailors, who featured heavily in his new naval reforms. But even here, the mercenary status of the sailors is never overly emphasised. There was a propensity to portray such people as an extension of the hired men philosophy, thus legitimising their ties to a more historic form of relationship with an Anglo-Saxon king. We cannot be sure of the status of the Frisians, but one thing is certain: they fought and died in Alfred’s new fleet.

The tenth century saw increasing amounts of foreigners at the English court. Notably, there were Bretons who had fled to King Edward the Elder in 919 after the Vikings had invaded their lands. King Athelstan harboured the Bretons and stood godfather to one, Alan. Alan was raised in England before Athelstan masterminded a campaign in Brittany to restore the Bretons to power. But these were foreigners who fought alongside the forces of the English king as allies and not as paid mercenaries. King Athelstan’s famous struggles with the confederacy of Scots, Vikings and Strathclyde Britons saw him enlist the help of the Vikings Egil and Thorolf, if we are to believe Egil’s Saga. Again, the exact nature of the relationship is not known. There is likely to have been more at stake than the mere payment of money for service, since a whole kingdom was up for grabs.

The new wave of Viking attacks which re-commenced around 990 saw an initial response by local leaders, who by now could operate independently on behalf of the Crown in their local areas. But England was still a remarkably rich land, more so now than it had ever been before. And it is in the reign of Æthelred II (979–1016) that the beginnings of a true ‘mercenary’ story can be told.

In 994 after Olaf Tryggvason and Swein Forkbeard together ravaged the south coast of England and the gafol of 16,000 pounds was paid to the force in Southampton, Æthelred came to an agreement with Olaf that if any other fleet should attack his coastline, Olaf would come to the aid of the English for as long as the king could provision him. Also, it was agreed that lands that harboured such hostile forces should be treated as an enemy by both parties. The arrangement was preceded by the same sponsorship once shown by Alfred to Guthrum, but more importantly included the heregeld of 22,000 pounds of silver. Despite the fact that Olaf returned to Norway, it is generally thought that a mercenary naval force would have remained to assist Æthelred in the spirit of the agreement. One Danish leader, Pallig, was even given lands in return for his service. This can be seen as an attempt to legitimise him above and beyond the mercenary to someone who had a vested interest in loyalty to the king, but Pallig’s subsequent treachery and return to the bosom of the enemy proved it to be a worthless policy. Pallig’s disloyalty probably led to the notorious St Brice’s Day massacre of 1002 whereby the king in desperation ordered the extermination of Danes who had settled in England.

Æthelred’s employment of Thorkell the Tall raises the question of the role of the later Anglo-Saxon housecarl. It has been argued that the institution developed out of the cult of the legendary Jomsvikings and flourished in England from the time of Cnut to the Battle of Hastings (1016–66). Mythology surrounds these warriors and the legal guild that is supposed to have accompanied them. Earl Godwin’s trial, for example, is supposed to be an example of such Scandinavian legal deliberations. Much ink has been spilled over the origins of these famous heavily armoured axemen, but the likelihood is that they were Danish versions of the Alfredian household retainer. Through the next generation up to the Norman Conquest they became an Anglo-Danish version of the same thing. A man described as a housecarl in one document may turn up elsewhere as a thegn or minister of the king. That they existed as an entity is not doubted: they were present at the translation of the remains of Ælfhere in 1023, are recorded at the side of Queen Emma in 1035 and some are recorded as dwelling on 15 acres of land in Wallingford. That the housecarls were financially supported is not in question. The Domesday Book specifically records some Dorset boroughs taxed for this very purpose. However, whether the institution simply became another layer of the king’s and various earls’ household retinues, is another matter. The Danish connotations with the institution are, however, inescapable: 87 per cent of all housecarls mentioned in documents bear names of Old Norse origin but it remains the case that their role did not differ much from that of the English thegnhood into which they settled, save for the stipend that they seem to have received.

There are one or two references to mercenaries that fall outside the above explanations. One of these is that of the rebel Earl Ælfgar’s Irishmen who accompanied him on his campaign in Herefordshire in 1055 and who almost certainly received payment for their services after waiting impatiently at Chester. The other is that of the Flemings who served with Earl Tostig after he presumably enticed them from Flanders with promises of riches in the campaign of 1066. Neither of these examples of earls buying the service of fighting men seem to have had any lasting impact on the Anglo-Saxon state in the way that the settlement of the housecarls did, but they serve as a reminder that if anyone had the political clout and the money, he could entice people to fight with him.

We have looked at the tributes and the payments made by English kings to foreign forces and discussed the background to mercenary employment in England during our period, but it is necessary to explore further another related dimension of warfare of the period, the naval aspect. Here, the mercenary once again plays a part in a very colourful history.

Naval Warfare

That the Anglo-Saxons were a competent seafaring nation is hardly a matter for dispute. The reputation given to King Alfred as the founder of a ‘royal’ navy hides the fact that before his impressive naval reforms of the 890s there were some perfectly successful defensive naval operations launched by the English rulers against Viking attackers. Ships were also used on the offensive as early as 633 when King Edwin of Northumbria conquered Anglesey and Man, and later in 684 when King Ecgfrith ravaged Ireland. There are some triumphant references to early successes in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle–an encounter at Sandwich in 851 masterminded by the Kentish King Athelstan resulted in the capture of nine enemy ships and the expulsion of a raiding Danish force. Even some of Alfred’s pre-reform naval forces could come back from an excursion with a story of great success, most notably in 875 and 882 when his forces captured some enemy vessels and again in 885 when an English naval force was sent to the mouth of the Stour in East Anglia and discovered and defeated sixteen ships only to lose the subsequent encounter.

The story of the early English navy falls into several categories. First, there is the territorially organised system of naval service based on the 5-hide unit and land-holding obligations subject to updated legislation from the king. Then, from at least the reign of Alfred the Great (871–99), we have the use of stipendiary sailors of mixed origins, mostly Frisians, Danes and Norwegians. Such mercenary bands form a significant part of naval provision in the decades preceding the Norman Conquest, as we have seen above from our accounts of heregeld payments. There is also the growing reliance upon coastal towns (particularly those on the south coast which subsequently became the Cinque Ports of later Medieval fame) to provide a naval contingent in return for certain privileges. On the eve of the Norman Conquest then, the English king could call upon ships from his own household (and from his earls, ealdormen and bishops), from the shipfyrd recruitment system, from paid mercenaries and from any merchant vessels he could press-gang into service. The result was a fleet of such enormity it was the envy of many other rulers in Christendom, some of whom specifically asked for its help. English fleets reached their zenith under King Edgar (959–75) and from this time were capable of regional and national patrols, of blockade duty, foreign expedition, of working in conjunction with land forces and, above all, of meeting an enemy in the open sea and defeating it. In fact, Edgar’s naval achievements are nothing short of remarkable if we are to believe John of Worcester’s summary in his account of the great king’s departure from this world:

During his life he formed a fleet of 3,600 stout ships, and after Easter, every year, he used to collect a squadron of 1200 ships on each of the eastern, western, and northern coast of the island; and make sail with the eastern squadron, until it fell in with the western, which then put about and sailed to the eastward while the western squadron sailed northward till it met with the northern, which, in turn, sailed to the west. Thus, the whole island was circumnavigated every summer, and these bold expeditions served at once for the defence of the realm against foreigners and to accustom himself and his people to warlike exercises.

So, not only did the English king have a great navy at his disposal, he also trained it once a year as well. This is a remarkable reference to the state of readiness for a force not found in any references to land armies of the period. But the numbers of vessels seem to be huge. There is yet to be an explanation for it. No account of the multitude of fleets summoned or bought throughout this whole period matches anything like this number. The very largest numbers in its hundreds. If Edgar truly had managed to establish such a force then it is little wonder that John of Worcester thought so highly of him. John may have been carrying a message of popular memory of a phenomenally powerful king, but doubt must necessarily continue to be cast on this figure of 3,600 ships. A reduction in number by a factor of ten might be more appropriate.

So where did it all start? Alfred’s ships, which are described by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for 896 as being ‘neither of Frisian design nor of Danish, but as it seemed to himself that they might be most useful’, were built in response to the raids of the Northumbrian Danes. The Danes came to Alfred’s shores in their ageing ‘askrs’ (warships). They were now to be met with an almost impossible sounding fleet of ships of twice the length, up to sixty oars or more, steadier and more responsive than the traditional Viking longship. The English ships were not built to the askr design, or to the cog-like Frisian merchant design known in northern waters. They were an innovation. Alfred had captured enemy ships in the past and was presumably able to have men examine their design. In fact, a later Medieval chronicle assigns this brave new fleet of Alfred’s to the year 877 and not 896. This much notwithstanding, these new ships were to be famously deployed off the southern coast of England in 896 with interesting consequences (see pp. 114–17). The references to the Frisian and high-born English crews of these new ships provide the only indication of how they were recruited. It would seem that these ships were the king’s own and not the ships raised by the territorial fyrd system.