The first drawing was a simple line drawn round the shadow of a man cast by the sun on a wall.

[1]

[1]

The mind of the painter must resemble a mirror, which always takes the color of the object it reflects and is completely occupied by the images of as many objects as are in front of it. Therefore you must know, O Painter! that you cannot be a good one if you are not the universal master of representing by your art every kind of form produced by nature. And this you will not know how to do if you do not see them, and retain them in your mind. Hence as you go through the fields, turn your attention to various objects, and, in turn, look now at this thing and now at that, collecting a store of diverse facts selected and chosen from those of less value.

But do not do like some painters who, when they are wearied with exercising their fancy dismiss their work from their thoughts and take exercise in walking for relaxation, but still keep fatigue in their mind, which, though they see various objects [around them], does not apprehend them; but even when they meet friends or relations, saluted by them, although they them, take no more cognizance if they had met so much empty air.

Painting surpasses all human works by the subtle considerations belonging to it. The eye, which is called the window of the soul, is the principal means by which the central sense can most completely and abundantly appreciate the infinite works of nature; and the ear is the second, which acquires dignity by hearing of the things the eye has seen. If you, historians, or poets, or mathematicians had not seen things with your eyes you could not report of them in writing.

And if you, O poet, tell a story with your pen, the painter with his brush can tell it more easily, with simpler completeness and less tedious to be understood. And if you call painting dumb poetry, the painter may call poetry blind painting. Now which is the worse defect? To be blind or dumb? Though the poet is as free as the painter in the invention of his fictions, they are not so satisfactory to men as paintings; for, though poetry is able to describe forms, actions, and places in words, the painter deals with the actual similitude of the forms, in order to represent them. Now tell me which is the nearer to the actual man; the name of man or the image of the man? The name of man differs in different countries, but his form is never changed but by death.

[2]

[2]

Though you may be able to tell or write the exact description of forms, the painter can so depict them that they will appear alive, with the shadow and light that show the expression of a face; which you cannot accomplish with the pen though it can be achieved by the brush.

[3]

[3]

The first thing in painting is that the objects it represents should appear in relief, and that the grounds surrounding them at different distances shall appear within the vertical plane of the foreground of the picture by means of the three branches of Perspectives, which are: the diminution in the distinctness of the forms of the objects; the diminution in their magnitude; and the diminution in their color. And of these three classes of Perspective the first results from [the structure of] the eye, while the other two are caused by the atmosphere that intervenes between the eye and the objects seen by it. The second essential in painting is appropriate action and a due variety in the figures, so that the men may not all look like brothers.

[4]

When you want to see if your picture corresponds throughout with the objects you have drawn from nature, take a mirror and look in that at the reflection of the real things, and compare the reflected image with your picture, and consider whether the subject of the two images duly corresponds in both, particularly studying the mirror. You should take the mirror for your guide—that is to say a flat mirror—because on its surface the objects appear in many respects as in a painting. Thus you see, in a painting done on a flat surface, objects that appear in relief, and in the mirror—also a flat surface—they look the same. The picture has one plane surface and the same with the mirror. The picture is intangible, insofar as that which appears round and prominent cannot be grasped in the hands; and it is the same with the mirror. And since you can see that the mirror, by means of outlines, shadows and lights, makes objects appear in relief, you, who have in your colors far stronger lights and shades than those in the mirror, can certainly, if you compose your picture well, make that also look like a natural scene reflected in a large mirror.

The boundaries of bodies are the least of all things. The proposition is proved to be true, because the boundary of a thing is a surface, which is not part of the body contained within that surface; nor is it part of the air surrounding that body, but is the medium interposed between the air and the body, as is proved in its place. But the lateral boundary of this body is the line forming the boundary of the surface, which line is of invisible thickness. Wherefore, O Painter, do not surround your bodies with lines, and above all when representing objects smaller than nature; for not only will their external outlines become indistinct, but their parts will be invisible from distance.

[5]

[5]

[5]

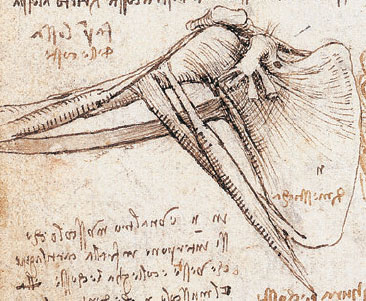

It is indispensable to a painter to be thoroughly familiar with the limbs in all the positions and actions of which they are capable, in the nude. [Then he will] know the anatomy of the sinews, bones, muscles, and tendons so that, in their various movements and exertions, he may know which nerve or muscle is the cause of each movement and show those only as prominent and thickened, and not the others all over [the limb], as many do. [Many poor painters], to seem great draughtsmen, draw their nude figures looking like wood, devoid of grace, so that you would think you were looking at a sack of walnuts rather than the human form, or a bundle of radishes rather than the muscles of figures.

[6]

[6]

[6]

How Light Should Be Thrown upon Figures.

The light must be arranged in accordance with the natural conditions under which you wish to represent your figures: that is, if you represent them in the sunshine, make the shadows dark with large spaces of light, and mark their shadows and those of all the surrounding objects strongly on the ground. And if you represent them as in dull weather, give little difference of light and shade, without any shadows at their feet.

If you represent them as within doors, make a strong difference between the lights and shadows, with shadows on the ground. If the window is screened and the walls white, there will be little difference of light. If it is lighted by firelight make the high lights ruddy and strong, and the shadows dark, and those cast on the walls and on the floor will be clearly defined and the farther they are from the body the broader and longer will they be. If the light is partly from the fire and partly from the outer day, that of day will be the stronger and that of the fire almost as red as fire itself.

Above all see that the figures you paint are broadly lighted and from above, that is to say, all living persons that you paint; for you will see that all the people you meet out in the street are lighted from above, and you must know that if you saw your most intimate friend with a light [on his face] from below you would find it difficult to recognize him.

Lights cast from a small window give strong differences of light and shade, all the more if the room lighted by it be large, and this is not good for painting.

[7]

An object will display the greatest difference of light and shade when it is seen in the strongest light, as by sunlight, or, at night, by the light of a fire. But this should not be much used in painting because the works remain crude and ungraceful.

An object seen in a moderate light displays little difference in the light and shade; and this is the case towards evening or when the day is cloudy, and works then painted are tender and every kind of face becomes graceful. Thus, in every thing light gives crudeness; too little prevents our seeing. The medium is best.

Make the shadow on figures correspond to the light and to the color of the body. When you draw a figure and you wish to see whether the shadow is the proper complement to the light, and neither redder nor [more] yellowish than in the nature of the color you wish to represent in shade, proceed thus. Cast a shadow with your finger on the illuminated portion, and if the accidental shadow that you have made is like the natural shadow cast by your finger on your work, well and good; and by putting your finger nearer or farther off, you can make darker or lighter shadows, which you must compare with your own [depiction].

The painter who draws merely by practice and by eye, without any reason, is like a mirror that copies everything placed in front of it without being conscious of their existence.

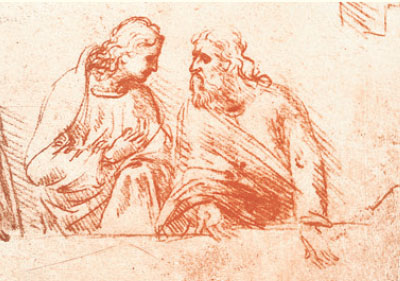

To draw figures for historical pictures, the painter must always study on the wall on which he is to picture a story the height of the position where he wishes to arrange his figures; and when drawing his studies for them from nature he must place himself with his eye as much below the object he is drawing as, in the picture, it will have to be above the eye of the spectator. Otherwise the work will look wrong.

Historical pictures ought not to be crowded and confused with too many figures.

[8]

[8]

[8]

[8]

To compose [groups of] figures in historical pictures, when you have well learnt perspective and have by heart the parts and forms of objects, you must go about, and constantly, as you go, observe, note, and consider the circumstances and behavior of men in talking, quarreling, or laughing or fighting together; the action of the men themselves and the actions of the bystanders, who separate them or who look on.

And take a note of them with slight strokes in a little book that you should always carry with you. And it should be of tinted paper, that it may not be rubbed out, but change the old [when full] for a new one; since these things should not be rubbed out but preserved with great care; for the forms, and positions of objects are so infinite that the memory is incapable of retaining them, wherefore keep these [sketches] as your guides and masters.

[9]

[9]

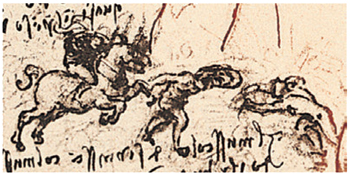

Of the Way of Represeenting a Battle.

First you must represent the smoke of artillery mingling in the air with the dust and tossed up by the movement of horses and the combatants. And this mixture you must express thus: the dust, being a thing of earth, has weight; and although from its fineness it is easily tossed up and mingles with the air, it nevertheless readily falls again.

[10]

[10]

The more the combatants are in this turmoil the less will they be seen, and the less contrast will there be in their lights and shadows.

[11]

[11]

[11]

And if you introduce horses galloping outside the crowd, make the little clouds of dust distant from each other in proportion to the strides made by the horses.

[12]

[12]

[12]

[12]

[12]

[12]

The air must be full of arrows in every direction, some shooting upwards, some falling, some flying level. The balls from the guns must have a train of smoke following their flight. The figures in the foreground you must make with dust on the hair and eyebrows and on other flat places likely to retain it. The conquerors you will make rushing onwards with their hair and other light things flying on the wind, with their brows bent down.

And if you make anyone fallen, you must show the place where he has slipped and been dragged along the dust into blood-stained mire; and in the half-liquid earth around show the print of the tramping of men and horses who have passed that way. Make also a horse dragging the dead body of his master, and leaving behind him, in the dust and mud, the track where the body was dragged along.

[13]

[13]

[13]

[13]

Make some one shielding his terrified eyes with one hand, the palm towards the enemy, while the other rests on the ground to support his half-raised body. Others represent shouting with their mouths open, and running away. You must scatter arms of all sorts among the feet of the combatants, as broken shields, lances, broken swords, and other such objects. And you must make the dead partly or entirely covered with dust, which is changed into crimson mire.

[14]

[14]

Some might be shown disarmed and beaten down by the enemy, turning upon the foe, with teeth and nails, to take an inhuman and bitter revenge. You might see some riderless horse rushing among the enemy, with his mane flying in the wind, and doing no little mischief with his heels. Some maimed warrior may be seen fallen to the earth, covering himself with his shield, while the enemy, bending over him, tries to deal him a deathstroke. There again might be seen a number of men fallen in a heap over a dead horse.

[15]

[15]

And there may be a river into which horses are galloping, churning up the water all round them into turbulent waves of foam and water, tossed into the air and among the legs and bodies of the horses. And there must not be a level spot that is not trampled with gore.

[16]

[16]

[16]

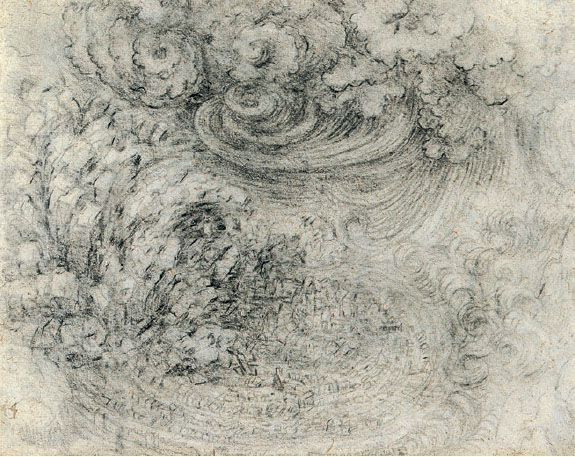

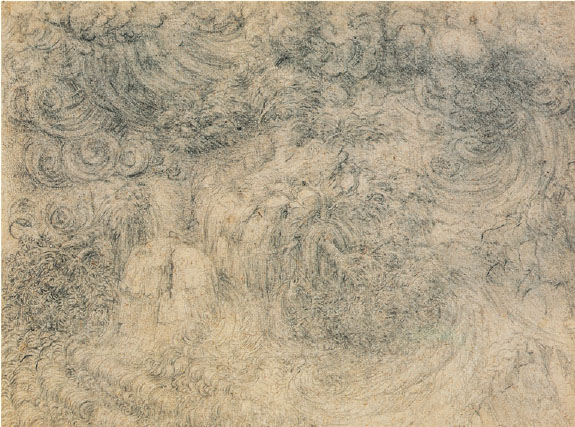

How to Present a Tempest.

If you wish to represent a tempest consider and arrange well its effects as seen, when the wind, blowing over the face of the sea and earth, removes and carries with it such things as are not fixed to the general mass. And to represent the storm accurately you must first show the clouds scattered and torn, and flying with the wind, accompanied by clouds of sand blown up from the seashore, and boughs and leaves swept along by the strength and fury of the blast and scattered with other light objects through the air.

[17]

[17]

Trees and plants must be bent to the ground, almost as if they would follow the course of the gale, with their branches twisted out of their natural growth and their leaves tossed and turned about.

Of the men who are there, some must have fallen to the ground and be entangled in their garments, and hardly to be recognized for the dust, while those who remain standing may be behind some tree, with their arms round it that the wind may not tear them away; others with their hands over their eyes for the dust, bending to the ground with their clothes and hair streaming in the wind.

Let the sea be rough and tempestuous and full of foam whirled among the lofty waves, while the wind flings the lighter spray through the stormy air, till it resembles a dense and swathing mist.

Of the ships that are therein, some should be shown with rent sails and the tatters fluttering through the air, with ropes broken and masts split and fallen. And the ship itself lying in the trough of the sea and wrecked by the fury of the waves with the men shrinking and clinging to the fragments of the vessel.

Make the clouds driven by the impetuosity of the wind and flung against the lofty mountain tops, and wreathed and torn like waves beating upon rocks; the air itself terrible from the deep darkness caused by the dust and fog and heavy clouds.

[18]

[18]

The air should be darkened by the heavy rain whose oblique descent, driven aslant by the rush of the winds, flies in drifts through the air. Let Eolus with his winds be shown entangling the trees floating uprooted, and whirling in the huge waves.

[19]

[19]

The waters that covered the fields with their waves should be in great part strewn with tables, bedsteads, boats, and various other contrivances.

[20]

[20]

All round should be seen venerable trees, uprooted and stripped by the fury of the winds. The air should be covered with dark clouds, riven by the forked flashes of the raging bolts of heaven, lighting up on all sides the depth of the gloom.

[21]

[21]

Let there be represented the summit of a rugged mountain with valleys surrounding its base, and on its sides let the surface of the soil be seen to slide, together with the small roots of the bushes, denuding great portions of the surrounding rocks. And descending ruinous from these precipices in its boisterous course, let it dash along and lay bare the twisted and gnarled roots of large trees overthrowing their roots upwards; and let the mountains, as they are scoured bare, discover the profound fissures made in them by ancient earthquakes.

The base of the mountains may be in great part clothed and covered with ruins of shrubs, hurled down from the sides of their lofty peaks, which will be mixed with mud, roots, boughs of trees, with all sorts of leaves thrust in with the mud and earth and stones. And into the depth of some valley may have fallen the fragments of a mountain forming a shore to the swollen waters of its river; which, having already burst its banks, will rush on in monstrous waves; and the greatest will strike upon and destroy the walls of the cities and farmhouses in the valley.

Darkness, wind, tempest at sea, floods of water, forests on fire, rain, bolts from heaven, earthquakes and ruins of mountains, overthrow of cities. Ships broken to pieces, beaten on rocks.

We know for certain that sight is one of the most rapid actions we can perform. In an instant we see an infinite number of forms; still we only take in thoroughly one object at a time.

Supposing that you, Reader, were to glance rapidly at the whole of this written page, you would instantly perceive that it was covered with various letters; but you could not, in the time, recognize what the letters were, nor what they were meant to tell. Hence you would need to see them word by word, line by line to be able to understand the letters. Again, if you wish to go to the top of a building, you must go up step by step; otherwise it will be impossible that you should reach the top.

Thus I say to you, whom nature prompts to pursue this art, if you wish to have a sound knowledge of the forms of subjects begin with the details of them, and do not go on to the second [step] till you have the first well fixed in memory and in practice. And if you do otherwise you will throw away your time, or certainly greatly prolong your studies. And remember to acquire diligence rather than rapidity.

[22]

Which is best, to draw from nature or from the antique? It is better to imitate the antique than modern work. But painting declines and deteriorates from age to age, when painters have no other standard than painting already done. Hence the painter will produce pictures of small merit if he takes for his standard the pictures of others as was seen in the painters after the Romans who always imitated each other and so their art constantly declined from age to age.

But if he will study from natural objects he will bear good fruit.

[23]

[23]

Many are they who have a taste and love for drawing, but no talent; and this will be discernible in boys who are not diligent and never finish their drawings with shading.

The youth should first learn perspective, then the proportions of objects. Then he may copy from some good master, to accustom himself to fine forms. Then [he may work] from nature, to confirm by practice the rules he has learnt. Then see for a time the works of various masters. Then get the habit of putting his art into practice and work.

[24]

[24]

When, O draughtsmen, you desire to find relaxation in games you should always practice such things as may be of use in your profession, by giving your eye good practice in judging of objects. Thus, to accustom your mind to such things, let one of you draw a straight line at random on a wall, and each of you, taking a blade of grass or of straw in his hand, try to cut it to the length that the line drawn appears to him to be, standing at a distance of 10 braccia; then each one may go up to the line to measure the length he has judged it to be. And he who has come nearest with his measure to the length of the pattern is the best man, and the winner, and shall receive the prize you have settled beforehand.

Again you should take foreshortened measures: that is, take a spear, or any other cane or reed, and fix on a point at a certain distance; and let each one estimate how many times he judges that its length will go into that distance. Again, who will draw best a line one braccio long, which shall be tested by a thread. Such games give occasion to good practice for the eye, which is of the first importance in painting.

[Also], when you look at a wall spotted with stains, or with a mixture of stones, if you have to devise some scene, you may discover a resemblance to various landscapes, beautified with mountains, rivers, rocks, trees, plains, wide valleys, and hills in varied arrangement; or again you may see battles and figures in action; or strange faces and costumes, and an endless variety of objects, which you could reduce to complete and well drawn forms. And these appear on such walls confusedly, like the sound of bells in whose jangle you may find any name or word you choose to imagine.

He is a poor disciple who does not excel his master.

[25]

[25]

Nor is the painter praiseworthy who does but one thing well, as the nude figure, heads, draperies, animals, landscapes or other such details, irrespective of other work; for there can be no mind so inept, that after devoting itself to one single thing and doing it constantly, it should fail to do it well.

A painter is not admirable unless he is universal. Some may distinctly assert that those persons are under a delusion who call that painter a good master who can do nothing well but a head or a figure. Certainly this is no great achievement; after studying one single thing for a life time who would not have attained some perfection in it? But, since we know that painting embraces and includes in itself every object produced by nature or resulting from the fortuitous actions of men, in short, all that the eye can see, he seems to me but a poor master who can only do a figure well.

For do you not perceive how many and various actions are performed by men only; how many different animals there are, as well as trees, plants, flowers, with many mountainous regions and plains, springs and rivers, cities with public and private buildings, machines, too, fit for the purposes of men, diverse costumes, decorations, and arts? And all these things ought to be regarded as of equal importance and value, by the man who can be termed a good painter.