That figure is most admirable which by its actions best expresses the passion that animates it.

[1]

[1]

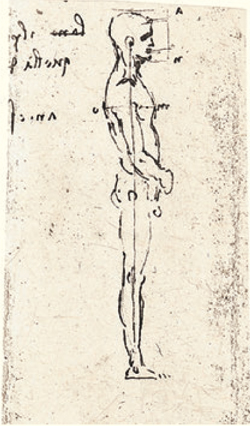

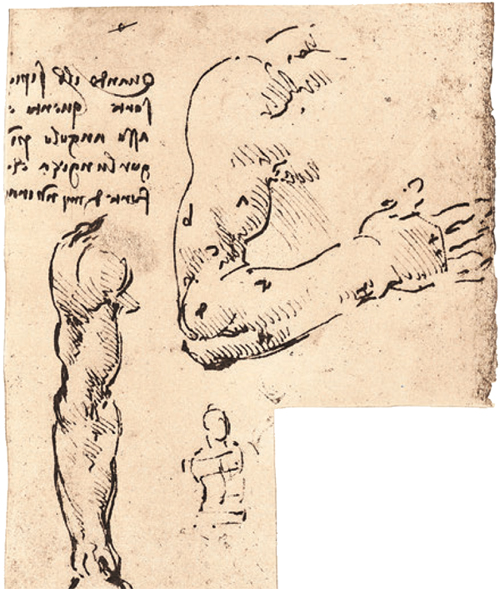

{a} Three are the principal muscles of the shoulder, that is b c d, and two are the lateral muscles which move it forward and backward, that is a o; a moves it forward, and o pulls it back; and b c d raises it; a b c moves it upwards and forwards, and c d o upwards and backwards. Its own weight almost suffices to move it downwards.

[2]

[2]

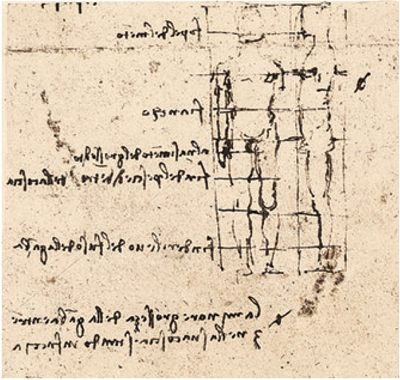

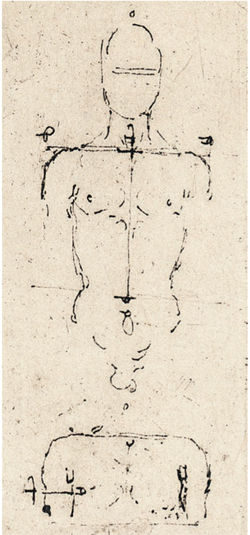

{a} Vitruvius, the architect, says in his work on architecture that the measurements of the human body are distributed by Nature as follows: that is, that 4 fingers make 1 palm and 4 palms make 1 foot, 6 palms make 1 cubit; 4 cubits make a man’s height. And 4 cubits make one pace and 24 palms make a man; and these measures he used in his building. If you open your legs so much as to decrease your height 1/14 and spread and raise your arms till your middle fingers touch the level of the top of your head you must know that the centre of the outspread limbs will be in the navel and the space between the legs will be an equilateral triangle.

The length of a man’s outspread arms is equal to his height.

{c} From the roots of the hair to the bottom of the chin is the tenth of a man’s height; from the bottom of the chin to the top of his head is one eighth of his height; from the top of the breast to the top of his head will be one sixth of a man. From the top of the breast to the roots of the hair will be the seventh part of the whole man. From the nipples to the top of the head will be the fourth part of a man. The greatest width of the shoulders contains in itself the fourth part of the man. From the elbow to the tip of the hand will be the fifth part of a man; and from the elbow to the angle of the armpit will be the eighth part of the man. The whole hand will be the tenth part of the man; the beginning of the genitals marks the middle of the man. The foot is the seventh part of the man. From the sole of the foot to below the knee will be the fourth part of the man. From below the knee to the beginning of the genitals will be the fourth part of the man. The distance from the bottom of the chin to the nose and from the roots of the hair to the eyebrows is, in each case the same, and like the ear, a third of the face.

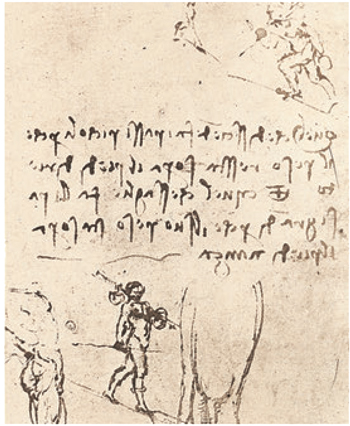

A picture or representation of human figures ought to be done in such a way that the spectator may easily recognize, by means of their attitudes, the purpose in their minds. Thus, if you have to represent a man of noble character in the act of speaking, let his gestures be such as naturally accompany good words; and, in the same way, if you wish to depict a man of a brutal nature, give him fierce movements; as with his arms flung out towards the listener, and his head and breast thrust forward beyond his feet, as if following the speaker’s hands. Thus it is with a deaf and dumb person who, when he sees two men in conversation—although he is deprived of hearing—can nevertheless understand, from the attitudes and gestures of the speakers, the nature of their discussion.

[3]

[3]

As regards the disposition of limbs in movement you will have to consider that when you wish to represent a man who, by some chance, has to turn backwards or to one side, you must not make him move his feet and all his limbs towards the side to which he turns his head. Rather must you make the action proceed by degrees and through the different joints; that is, those of the foot, the knee and the hip and the neck. And if you set him on the right leg, you must make the left knee bend inwards, and let his foot be slightly raised on the outside, and the left shoulder be somewhat lower than the right, while the nape of the neck is in a line directly over the outer ankle of the left foot. And the left shoulder will be in a perpendicular line left above the toes of the right foot. And always set your figures so that the side to which the head turns is not the side to which the breast faces, since nature for our convenience has made us with a neck that bends with ease in many directions, the eye wishing to turn to various points, the different joints. And if at any time you make a man sitting with his arms at work on something that is sideways to him, make the upper part of his body turn upon the hips.

A painter who has clumsy hands will paint similar hands in his works, and the same will occur with any limb, unless long study has taught him to avoid it. Therefore, O Painter, look carefully what part is most ill-favored in your own person and take particular pains to correct it in your studies. For if you are coarse, your figures will seem the same and devoid of charm; and it is the same with any part that may be good or poor in yourself; it will be shown in some degree in your figures.

[4]

[4]

{a} In kneeling down a man will lose the fourth part of his height.

{b} When a man kneels down with his hands folded on his breast, the navel will mark half his height and likewise the points of the elbows.

{c} Half the height of a man who sits—that is from the seat to the top of the head—will be where the arms fold below the breast, and below the shoulders. The seated portion—that is from the seat to the top of the head—will be more than half the man’s [whole height] by the length of the scrotum.

The width of a man under the arms is the same as at the hips.

The opening of the ear, the joint of the shoulder, [and] that of the hip and the ankle are in perpendicular lines.

a n is equal to m o.

Of the loins, when bent.

The loins or backbone being bent. The breasts are always lower than the shoulder blades of the back.

If the breast bone is arched the breasts are higher than the shoulder blades.

If the loins are upright the breast will always be found at the same level as the shoulder blades.

Top of the chin.

Hip.

The insertion of the middle finger.

The end of the calf of the leg on the inside of the thigh.

The end of the swelling of the shin bone of the leg.

The smallest thickness of the leg goes three times into the thigh seen in front.

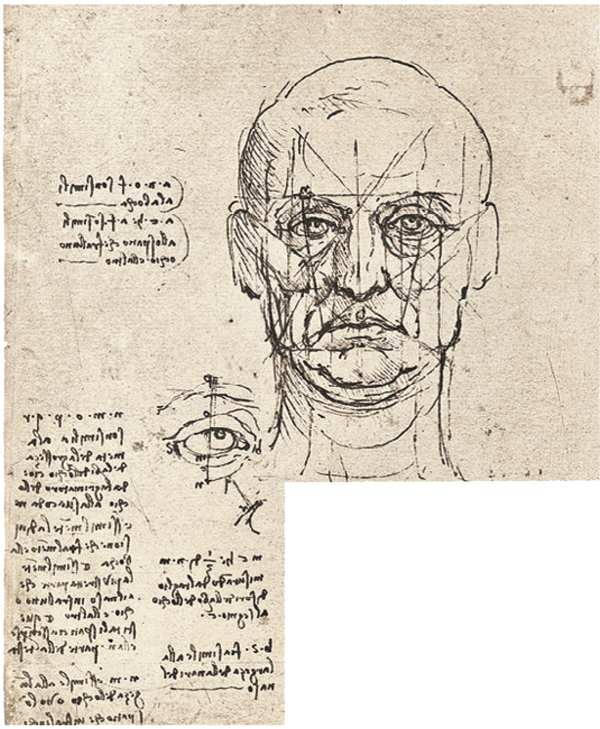

The distance from the attachment of one ear to the other is equal to that from the meeting of the eyebrows to the chin, and in a fine face the width of the mouth is equal to the length from the parting of the lips to the bottom of the chin.

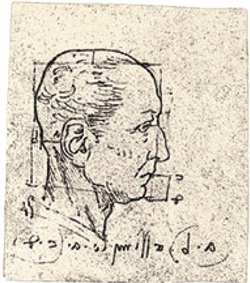

The ear is exactly as long as the nose. The parting of the mouth seen in profile slopes to the angle of the jaw. The ear should be as high as from the bottom of the nose to the top of the eyelid. The space between the eyes is equal to the width of an eye. The ear is over the middle of the neck, when seen in profile.

a n o f are equal to the mouth.

a c and a f are equal to the space between one eye and the other.

n m o p q r are equal to half the width of the eyelids, that is, from the inner corner of the eye to its outer corner; and in like manner the division between the chin and the mouth; and in the same way the narrowest part of the nose between the eyes. And these spaces, each in itself, is the 19th part of the head.

m n is equal to the length of the eye or of the space between the eyes.

m c is 1/3 of n m measuring from the outer corner of the eyelids to the letter c.

b s will be equal to the width of the nostril.

The cut or depression below the lower lip of the mouth is halfway between the bottom of the nose and the bottom of the chin.

The face forms a square in itself; that is, its width is from the outer corner of one eye to the other, and its height is from the very top of the nose to the bottom of the lower lip of the mouth; then what remains above and below this square amounts to the height of such another square. a b is equal to the space between c d.

(a b) is equal to (c d).

From the eyebrow to the junction of the lip with the chin, and the angle of the jaw and the upper angle where the ear joins the temple will be a perfect square. And each side by itself is half the head.

The hollow of the cheekbone occurs halfway between the tip of the nose and the top of the jawbone, which is the lower angle of the setting of the ear, in the frame here represented.

From the angle of the eye-socket to the ear is as far as the length of the ear, or the third of the face.

From a to b—that is to say from the roots of the hair in front to the top of the head—ought to be equal to c d—that is from the bottom of the nose to the meeting of the lips in the middle of the mouth. From the inner corner of the eye m to the top of the head a is as far as from m down to the chin s.

s c f b are all at equal distances from each other.

The space between the parting of the lips [the mouth] and the base of the nose is one-seventh of the face.

The space from the mouth to the bottom of the chin c d is the fourth part of the face and equal to the width of the mouth.

The space from the chin to the base of the nose e f is the third part of the face and equal to the length of the nose and to the forehead.

The distance from the middle of the nose to the bottom of the chin g h, is half the length of the face.

The distance from the top of the nose, where the eyebrows begin, to the bottom of the chin, i k, is two thirds of the face.

The space from the parting of the lips to the top of the chin i m, that is where the chin ends and passes into the lower lip of the mouth, is the third of the distance from the parting of the lips to the bottom of the chin and is the twelfth part of the face. From the top to the bottom of the chin m n is the sixth part of the face and is the fifty-fourth part of a man’s height.

From the farthest projection of the chin to the throat o p is equal to the space between the mouth and the bottom of the chin, and a fourth of the face.

The distance from the top of the throat to the pit of the throat below q r is half the length of the face and the eighteenth part of a man’s height.

From the chin to the back of the neck s t, is the same distance as between the mouth and the roots of the hair that is three-quarters of the head.

From the chin to the jawbone v x is half the head and equal to the thickness of the neck in profile.

The thickness of the head from the brow to the nape is one and one-half that of the neck.

From the roots of the hair to the top of the breast a b is the sixth part of the height of a man and this measure is equal.

a b, c d, e f, g h, i k are equal to each other in size excepting that d f is accidental.

a b c are equal to each other and to the foot and to the space between the nipple and the navel. d c will be the third part of the whole man.

From b to a is one head, as well as from c to a and this happens when the elbow forms a right angle.

f g is the part of a man and is equal to g h and measures a cubit.

[5]

[5]

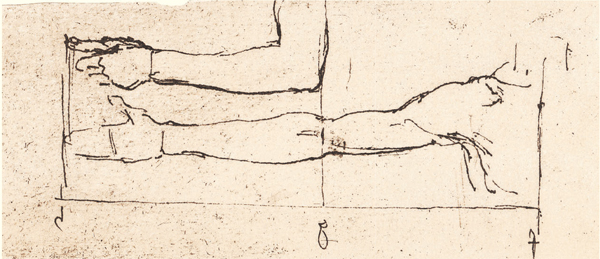

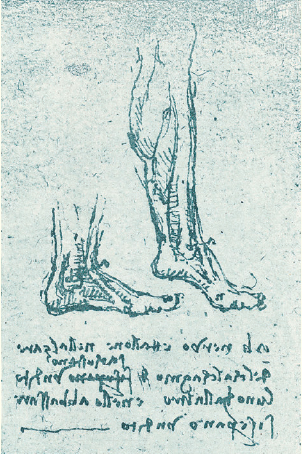

{a} a b c are equal; a to b is two feet—that is to say measuring from the heel to the tip of the great toe.

{b} m n o are equal. The narrowest width of the leg seen in front goes eight times from the sole of the foot to the joint of the knee, and is the same width as the arm, seen in front at the wrist, and as the longest measure of the ear, and as the three chief divisions into which we divide the face; and this measurement goes four times from the wrist joint of the hand to the point of the elbow. The foot is as long as the space from the knee between a and b; and the patella of the knee is as long as the leg between r and s.

{c} From the tip of the longest finger of the hand to the shoulder joint is four hands or, if you will, four faces.

The least thickness of the leg in profile goes six times from the sole of the foot to the knee joint and is the same width as the space between the outer corner of the eye and the opening of the ear, and as the thickest part of the arm seen in profile and between the inner corner of the eye and the insertion of the hair.

{d} a b c [d] are all relatively of equal length. c d goes twice from the sole of the foot to the center of the knee and the same from the knee to the hip.

{e} a b c are equal and each interval is two heads.

a e is equal to the palm of the hand, r f and o g are equal to half a head and each goes four times into a b and b c. From c to m is a head; m n is 1/3 of a head and goes six times into c b and into b a;

a b loses 1/7 of its length when the arm is extended; c b never alters; o will always be the middle point between a and s.

y l is the fleshy part of the arm and measures one head; and when the arm is bent this shrinks 2/5 of its length; o a in bending loses 1/6 and so does o r.

a b is 1/7 of r c.

f s will be 1/8 of r c, and each of those two measurements is the largest of the arm; k h is the thinnest part between the shoulder and the elbow and it is 1/8 of the whole arm r c; o p is 1/3 of r l; c z goes 13 times into r c.

a b goes four times into a c and nine into a m.

[6]

The greatest thickness of the arm between the elbow and the hand goes six times into a m and is equal to r f. The greatest thickness of the arm between the shoulder and the elbow goes four times into c m, and is equal to h n g. The smallest thickness of the arm above the elbow x y is not the base of a square, but is equal to half the space h 3, which is found between the inner joint of the arm and the wrist joint.

The width of the wrist goes 12 times into the whole arm; that is, from the tip of the fingers to the shoulder joint; that is, three times into the hand and nine into the arm.

When the arm is bent at an angle at the elbow, it will produce some angle; the more acute the angle is, the more will the muscles within the bend be shortened; while the muscles outside will become of greater length than before. As is shown in the example; d c e will shrink considerably; and b n will be much extended.

The principal movements of the hand are 10; that is forwards, backwards, to right and to left, in a circular motion, up or down, to close and to open, and to spread the fingers or to press them together.

From the outside part of one shoulder to the other is the same distance as from the top of the breast to the navel and this measure goes four times from the sole of the foot to the lower end of the nose.

The [thickness of] the arm where it springs from the shoulder in front goes six times into the space between the two outside edges of the shoulders and three times into the face, and four times into the length of the foot and three into the hand, inside or outside.

a b c are equal to each other and to the space from the armpit of the shoulder to the genitals and to the distance from the tip of the fingers of the hand to the joint of the arm, and to the half of the breast; and you must know that c b is the third part of the height of a man from the shoulders to the ground; d e f are equal to each other and equal to the greatest width of the shoulders.

The torso a b in its thinnest part measures a foot; and from a to b is two feet, which makes two squares to the seat—its thinnest part goes 3 times into the length, thus making three squares.

The greatest thickness of the calf of the leg is at a third of its height a b, and is a twentieth part thicker than the greatest thickness of the foot.

a c is the half of the head, and equal to d b and to the insertion of the five toes e f. d k diminishes one-sixth in the leg g h. g h is 1/3 of the head; m n increases one-sixth from a c and is 7/12 of the head. o p is 1/10 less than d k and is 6/17 of the head. a is at half the distance between b q, and is 1/4 of the man. r is halfway between s and b. The concavity of the knee outside r is higher than that inside a. The half of the whole height of the leg from the foot [to the point] r, is halfway between the prominence s and the ground b. v is halfway between t and b. The thickness of the thigh seen in front is equal to the greatest width of the face, that is, 2/3 of the length from the chin to the top of the head; z r is 5/6 of 7 to v; m n is equal to 7 v and is 1/4 of r b, x y goes three times into r b, and into r s.

The sinew that guides the leg, and which is connected with the patella of the knee, feels it a greater labor to carry the man upwards, in proportion as the leg is more bent; and the muscle that acts upon the angle made by the thigh where it joins the body has less difficulty and has a less weight to lift, because it has not the [additional] weight of the thigh itself. And besides this it has stronger muscles, being those which form the buttock.

a b the tendon and ankle in raising the heel approach each other by a finger’s breadth; in lowering it they separate by a finger’s breadth.

a d is a head’s length. c b is a head’s length.

The four smaller toes are all equally thick from the nail at the top to the bottom, and are 1/13 of the foot.

a n b are equal;

c n d are equal; n c makes two feet;

n d makes two feet.

On painting

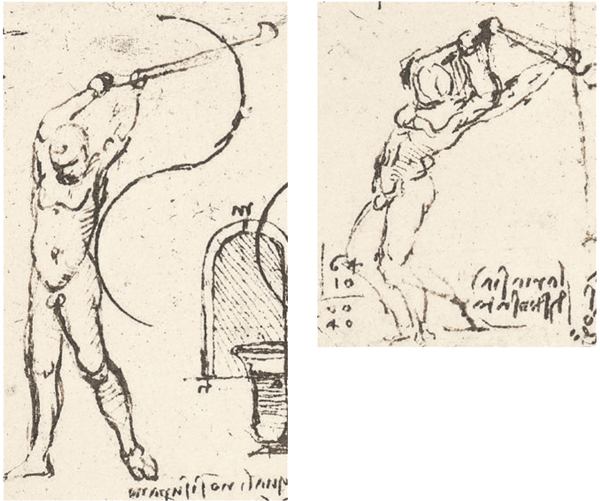

Of the nature of movements in man. Do not repeat the same gestures in the limbs of men unless you are compelled by the necessity of their action, as is shown in a b.

Of delivering a blow to the right or left.

When two men are at the opposite ends of a plank that is balanced, and if they are of equal weight, and if one of them wants to make a leap into the air, then his leap will be made down from his end of the plank and the man will never go up again but must remain in his place till the man at the other end dashes up the board.

A sitting man cannot raise himself if that part of his body which is front of his axis [center of gravity] does not weigh more than that which is behind that axis [or centre] without using his arms.

A man who is mounting any slope finds that he must involuntarily throw the most weight forward, on the higher foot, rather than behind—that is, in front of the axis and not behind it. Hence a man will always, involuntarily, throw the greater weight towards the point whither he desires to move than in any other direction.

The faster a man runs, the more he leans forward towards the point he runs to and throws more weight in front of his axis than behind. A man who runs down hill throws the axis onto his heels, and one who runs up hill throws it into the points of his feet; and a man running on level ground throws it first on his heels and then on the points of his feet.

This man cannot carry his own weight unless, by drawing his body back, he balances the weight in front, in such a way as that the foot on which he stands is the center of gravity.

When a man wants to stop running and check the impetus, he is forced to hang back and take short quick steps.

The higher the step is that a man has to mount, the farther forward will he place his head in advance of his upper foot, so as to weigh more on a than on b; this man will not be on the step m. As is shown by the line g f.

A man coming down hill takes little steps, because the weight rests upon the hinder foot, while a man mounting takes wide steps, because his weight rests on the foremost foot.

[8]

[8]

The center of gravity of a man who lifts one of his feet from the ground always rests on the center of the sole of the foot [he stands on].

A man, in going up stairs involuntarily throws so much weight forward and on the side of the upper foot as to be a counterpoise to the lower leg, so that the labor of this lower leg is limited to moving itself.

The first thing a man does in mounting steps is to relieve the leg he is about to lift of the weight of the body which was resting on that leg; and besides this, he gives to the opposite leg all the rest of the bulk of the whole man, including [the weight of] the other leg; he then raises the other leg and sets the foot upon the step to which he wishes to raise himself. Having done this he restores to the upper foot all the weight of the body and of the leg itself, and places his hand on his thigh and throws his head forward and repeats the movement towards the point of the upper foot, quickly lifting the heel of the lower one; and with this impetus he lifts himself up and at the same time extends the arm which rested on his knee; and this extension of the arm carries up the body and the head, and so straightens the spine which was curved.

I ask the weight [pressure] of this man at every degree of motion on these steps, what weight he gives to b and to c.

Observe the perpendicular line below the centre of gravity of the man.

In going up stairs if you place your hands on your knees all the labor taken by the arms is removed from the sinews at the back of the knees.

Young boys have their joints just the reverse of those of men, as to size. Little children have all the joints slender and the portions between them are thick; and this happens because nothing but the skin covers the joints without any other flesh and has the character of sinew, connecting the bones like a ligature. And the fat fleshiness is laid on between one joint and the next, and between the skin and the bones.

But, since the bones are thicker at the joints than between them, as a mass grows up the flesh ceases to have that superfluity which it had, between the skin and the bones; whence the skin clings more closely to the bone and the limbs grow more slender. But since there is nothing over the joints but the cartilaginous and sinewy skin this cannot dry up, and, not drying up, cannot shrink.

Thus, and for this reason, children are slender at the joints and fat between the joints; as may be seen in the joints of the fingers, arms, and shoulders, which are slender and dimpled, while in man on the contrary all the joints of the fingers, arms, and legs are thick; and wherever children have hollows men have prominences.

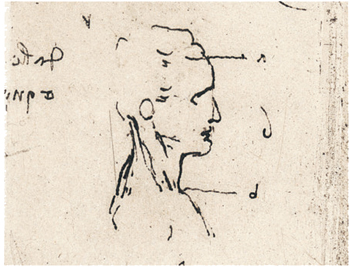

Old men ought to be represented with slow and heavy movements, their legs bent at the knees, when they stand still, and their feet placed parallel and apart; bending low with the head leaning forward, and their arms but little extended.

Women must be represented in modest attitudes, their legs close together, their arms closely folded, their heads inclined and somewhat on one side.

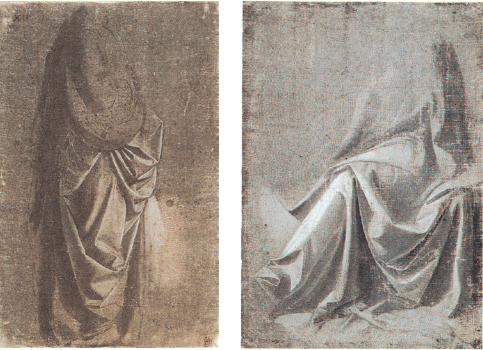

[9]

[9]

[9]

[9]

Figures dressed in a cloak should not show the shape so much as that the cloak looks as if it were next the flesh; since you surely cannot wish the cloak to be next the flesh, for you must suppose that between the flesh and the cloak there are other garments that prevent the forms of the limbs appearing distinctly through the cloak. And those limbs that you allow to be seen, you must make thicker so that the other garments may appear to be under the cloak.

Only give something of the true thickness of the limbs to a nymph or an angel, which are represented in thin draperies, pressed and clinging to the limbs of the figures by the action of the wind.

When representing a human figure or some graceful animal, be careful to avoid a wooden stiffness; that is to say, make them move with equipoise and balance so as not to look like a piece of wood; but those you want to represent as strong you must not make so, excepting in the turn of the head.

Every part of the whole must be in proportion to the whole. Thus, if a man is of a stout short figure he will be the same in all his parts: that is, with short and thick arms, wide thick hands, with short fingers with their joints of the same character, and so on with the rest. I would have the same thing understood as applying to all animals and plants; in diminishing, [the various parts] do so in due proportion to the size, as also in enlarging.

The limbs should be adapted to the body with grace and with reference to the effect that you wish the figure to produce. And if you wish to produce a figure that shall of itself look light and graceful you must make the limbs elegant and extended, and without too much display of the muscles; and those few that are needed for your purpose you must indicate softly, that is, not very prominent and without strong shadows; the limbs, and particularly the arms easy; that is, none of the limbs should be in a straight line with the adjoining parts.

And if the hips, which are the pole of a man, are by reason of his position, placed so that the right is higher than the left, make the point of the higher shoulder in a perpendicular line above the highest prominence of the hip, and let this right shoulder be lower than the left. Let the pit of the throat always be over the center of the joint of the foot on which the man is leaning. The leg that is free should have the knee lower than the other, and near the other leg.

The positions of the head and arms are endless and I shall therefore not enlarge on any rules for them. Still, let them be easy and pleasing, with various turns and twists, and the joints gracefully bent.

And again, remember to be very careful in giving your figures limbs, that they must appear to agree with the size of the body and likewise to the age. Thus a youth has limbs that are not very muscular not strongly veined, and the surface is delicate and round, and tender in color. In man the limbs are sinewy and muscular, while in old men the surface is wrinkled, rugged and knotty and the sinews very prominent.

O Anatomical Painter! beware lest the too strong indication of the bones, sinews and muscles be the cause of your becoming wooden in your painting, by your wish to make your nude figures display all their feeling. Therefore, in endeavoring to remedy this, look in what manner the muscles clothe or cover their bones in old or lean persons; and besides this, observe the rule as to how these same muscles fill up the spaces of the surface that extend between them, which are the muscles that never lose their prominence in any amount of fatness; and which too are the muscles of which the attachments are lost to sight in the very least plumpness. And in many cases several muscles look like one single muscle in the increase of fat; and in many cases, in growing lean or old, one single muscle divides into several muscles.

Again, do not fail [to observe] the variations in the forms of the above mentioned muscles, round and about the joints of the limbs of any animal, as caused by the diversity of the motions of each limb; for on some side of those joints the prominence of these muscles is wholly lost in the increase or diminution of the flesh of which these muscles are composed.